Architectural Japonisme, Part I

Early Architectural Japonisme in America, 1850's-1910's

with some references to modern architecture

________________________

Greene and Greene

Charles Sumner Greene (1868–1957) & Henry Mather Greene (1870–1954)

Part I: The Physical and Spiritual Presence of Japan

Lecture handout 2015.11.5, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 24

Yasutaka Aoyama

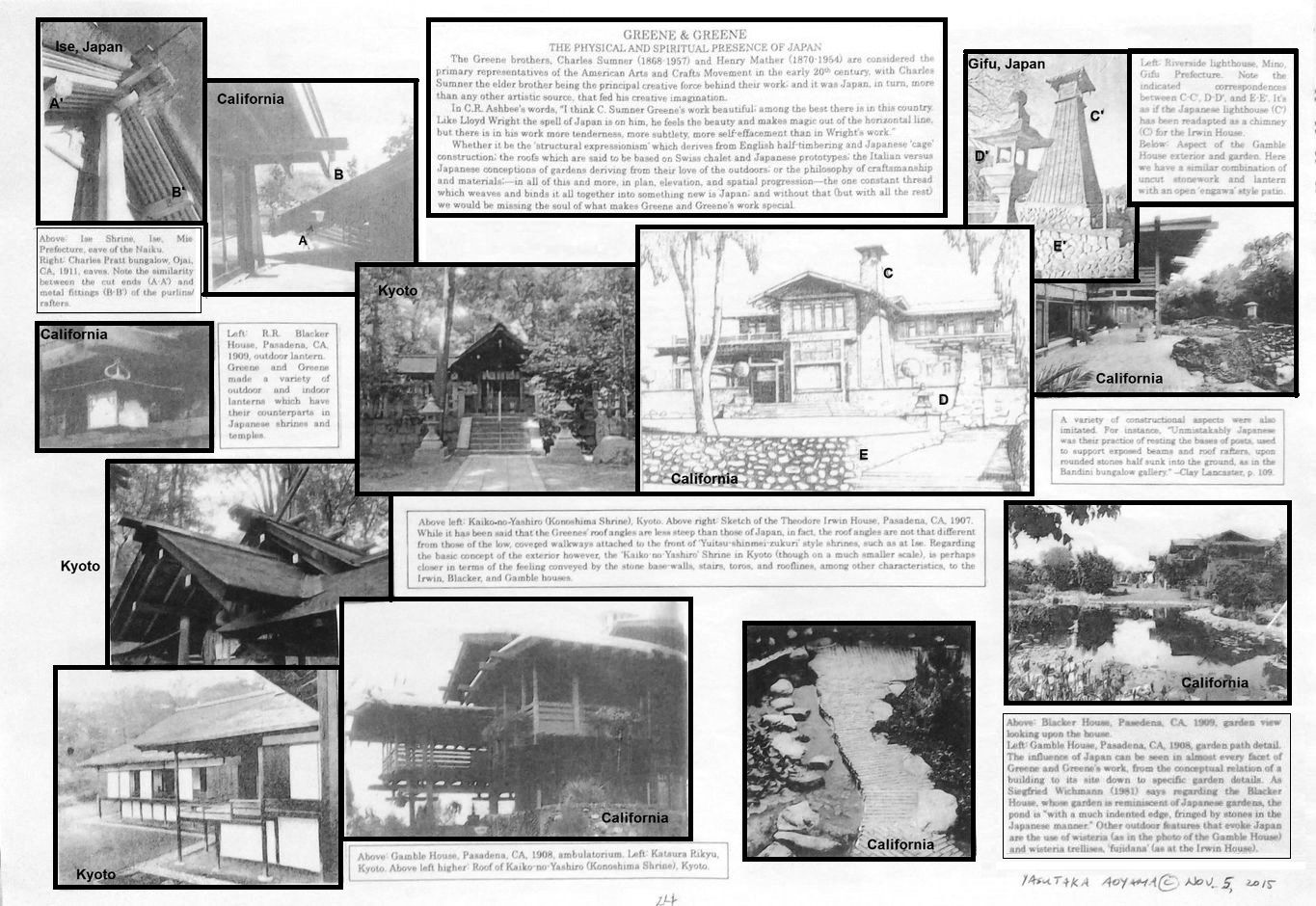

The Greene brothers, Charles Sumner and Henry Mather, are considered the primary representatives of the American Arts and Crafts Movement of the early 20th century, with Charles Sumner, the elder brother, being the principal creative force behind their work; and it was Japan in turn, more than any other artistic source, that fed his creative imagination.

In the words of Charles Robert Ashbee, of English Arts and Crafts renown, "I think C. Sumner Greene's work beautiful; among the best there is in this country (meaning the USA). Like Lloyd Wright the spell of Japan is on him, he feels the beauty and makes magic out of the horizontal line, but there is in his work more tenderness, more subtlety, more self-effacement than in Wright's work."

Vincent Scully, the pre-eminent historian of 19th century American architecture wrote: "Their use of materials---rough wood, cedar shakes, and cobblestones---also grows out of the use of natural materials of the shingle style [a Japanese influenced style according to Scully] but in a sense exaggerates it, insisting obsessively upon the total articulation of each element. Also significant in their work is a strong oriental influence, the apotheosis of that insistent relationship with Japanese framing and spatial techniques which had been important since the 70's [1870's]." (The Shingle Style and The Stick Style, Revised Edition, 1971, p.157)

While Henry-Russell Hitchcock, usually sparing in his comments regarding the role of Japan in his Architecture: Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (The Pelican History of Art), considers the Greene's houses "most interesting for their successful assimilation of oriental influences", writing: "Shingled walls, low-pitched and wide-spreading gables, and extensive porte-cocheres and verandas of stick-work surpassing in virtuosity those of the Stick Style, were combined by the Greenes in rather loosely organized compositions. Less formal and regular than Wright's Prairie Houses, theirs are executed throughout with a craftsmanship in wood rivalling that of the Japanese, whom they, like Wright, so much admired." (1977, p. 452)

Other architectural historians have characterized it in various ways; but whether it be the 'structural expressionism' of their designs which derives from English half-timbering and Japanese 'cage' construction; the roofs which are said to be based on Swiss chalet and Japanese prototypes; the Italian and Japanese conceptions of gardens deriving from their love of the outdoors; or the philosophy of craftsmanship and materials;---in all of this and more, in plan, elevation, and spatial progression---the one constant thread which weaves and binds it all together into something new---is Japan; and without that (but with all the rest) we would be not missing the soul of what makes Greene and Greene's work special?

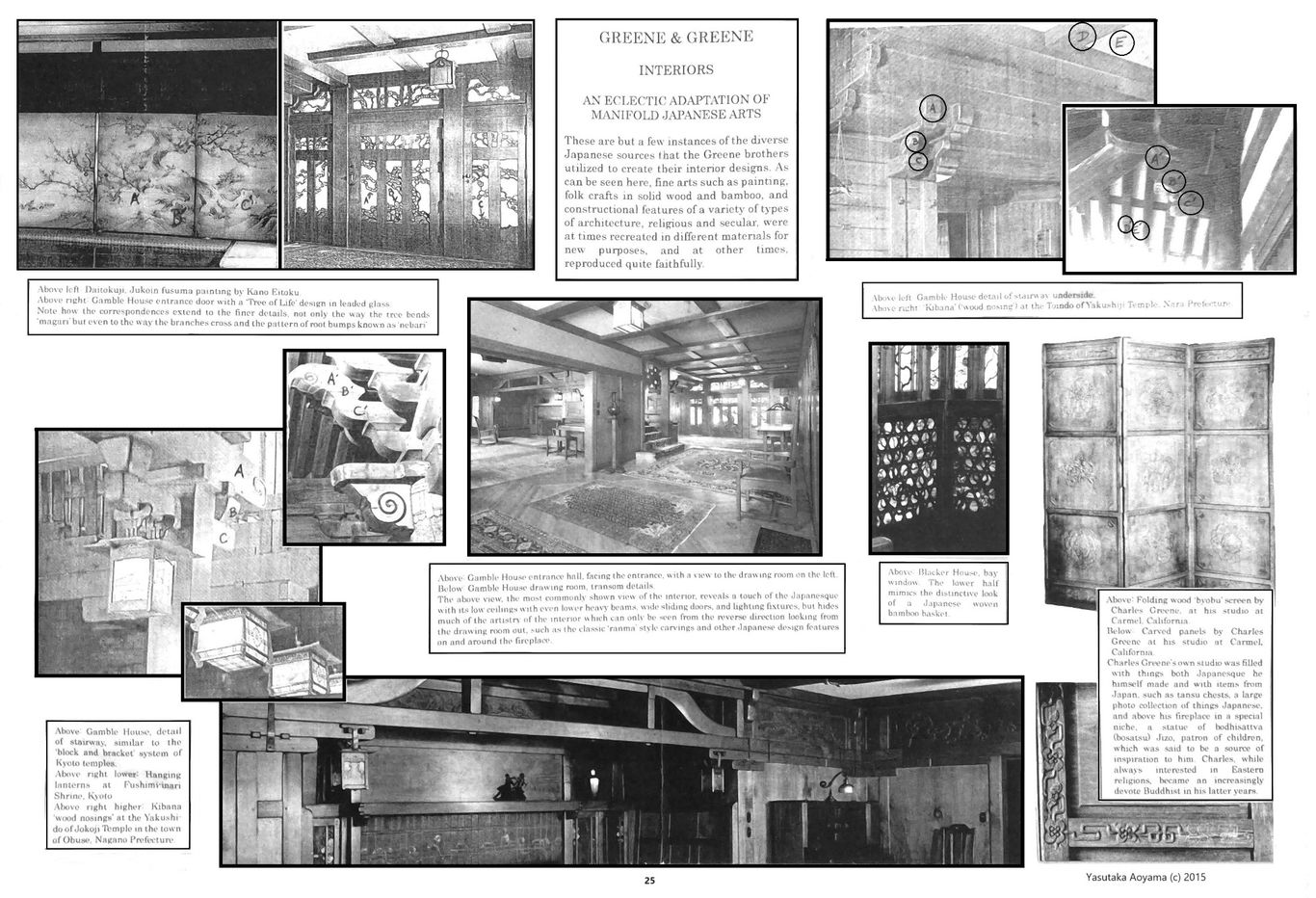

Greene and Greene

Part II: Interiors

An Eclectic Adaptation of Manifold Japanese Arts

Lecture handout 2015.11.5, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 25

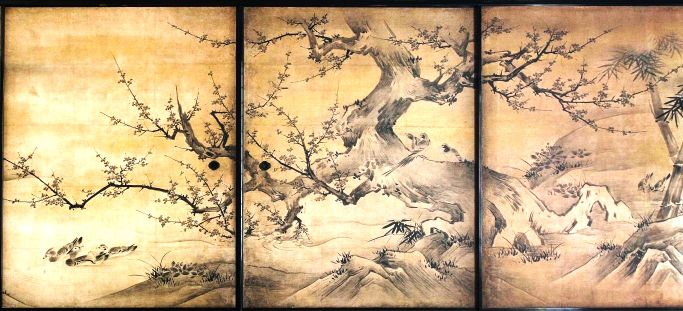

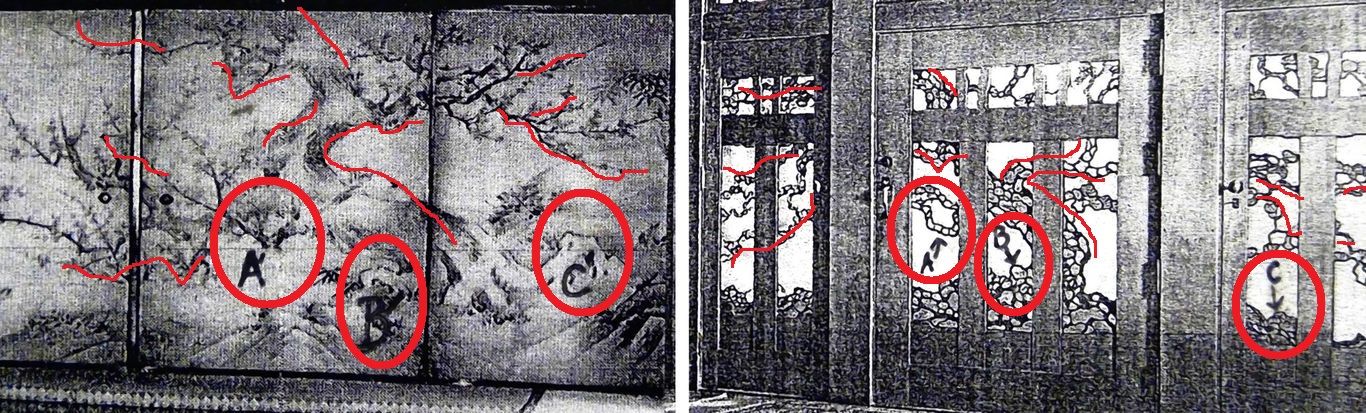

Below: Close up of the Daitokuji Temple Jukoin fusuma (sliding door panel) by Kano Eitoku (left) and the Gamble House entrance door with the 'Tree of Life' design in leaded glass (right). Note how the correspondences extend to the finer details (e.g. A=A', B=B', C=C') not only in the pronounced way in which the tree bends and extends horizontally known as 'magari' but even to the way the branches cross and the pattern of root bumps know as 'nebari'. In Japan the aesthetic appreciation of the details of garden tree shape, like bonsai, especially their sideways extension was a matter of high connoisseurship.

Bottom two photos from Wikipedia.

________________________

McKim, Mead and White

Charles Follen McKim (1847–1909), William Rutherford Mead (1846–1928) and Stanford White (1853–1906)

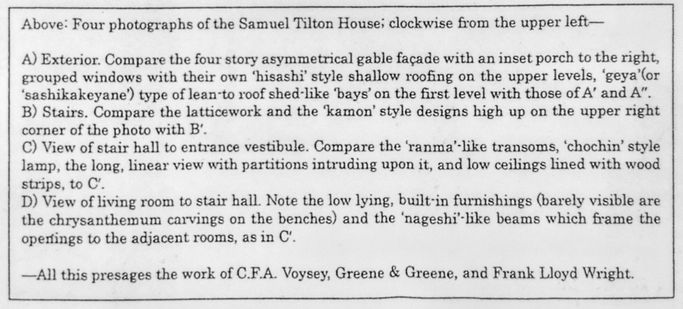

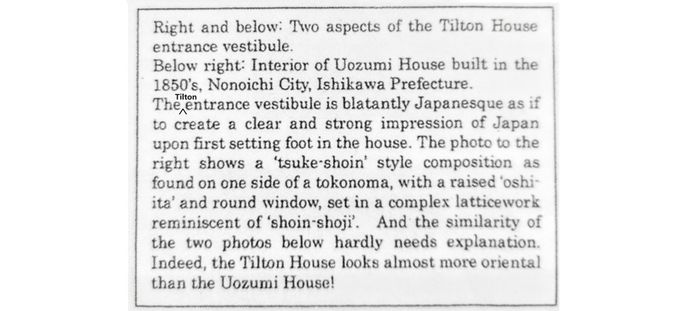

The Samuel Tilton House, American 'Minka Style'

Lecture handout 2015.10.30, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 27

Yasutaka Aoyama

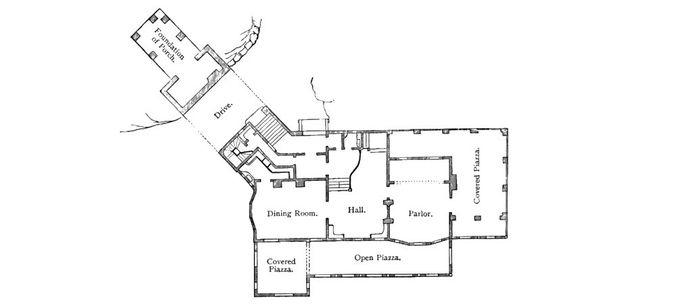

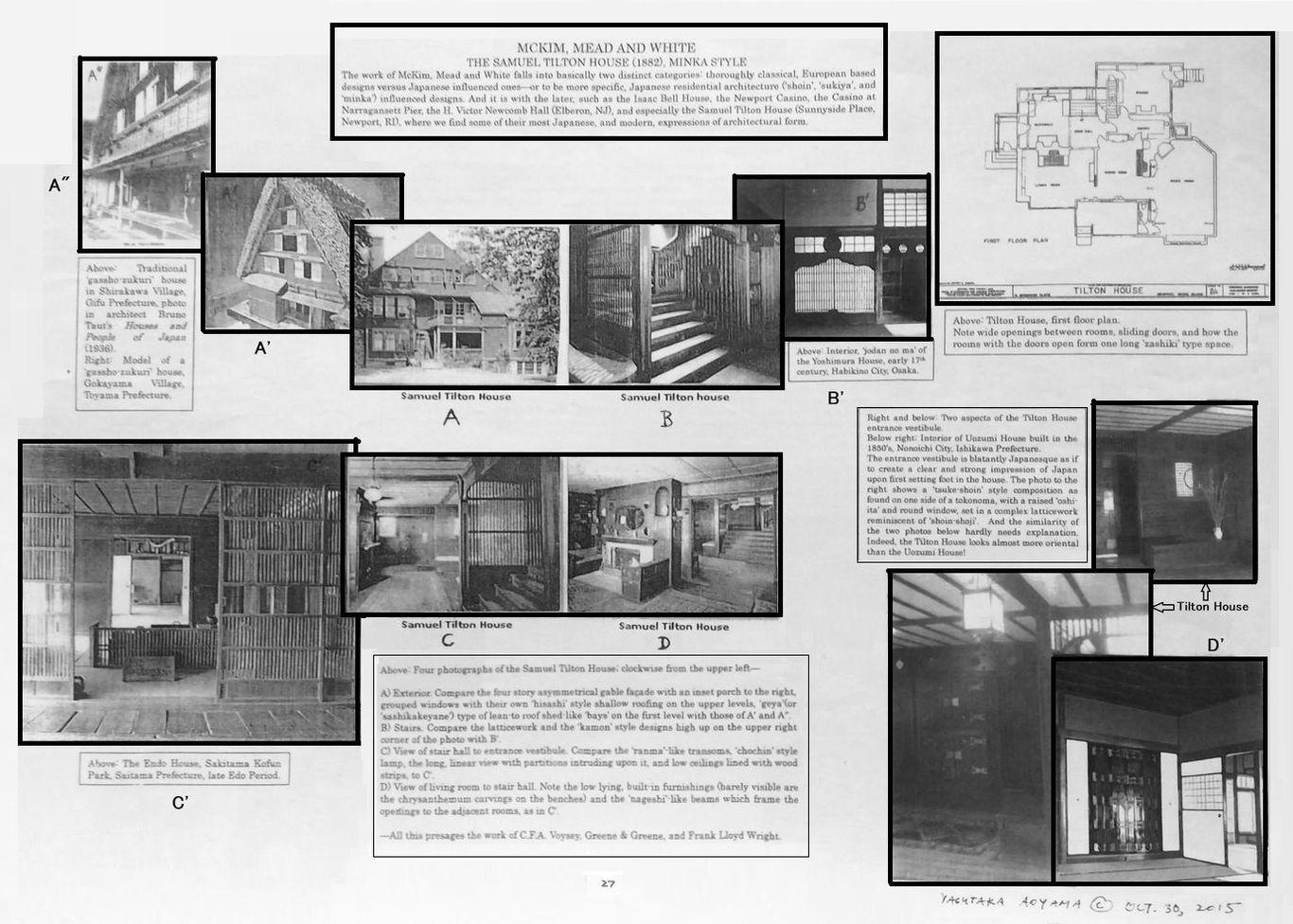

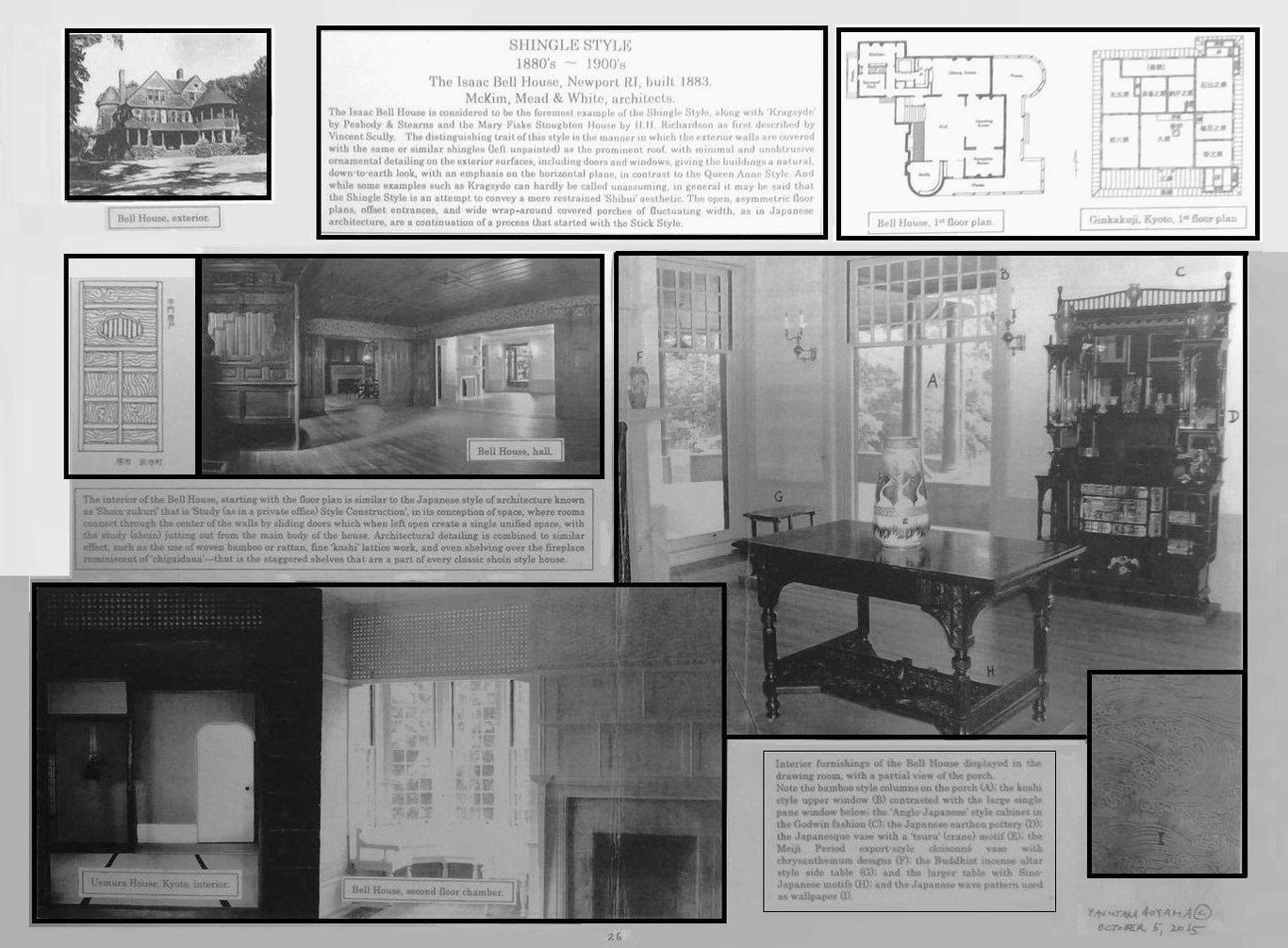

The work of McKim, Mead and White falls into basically two distinct categories: thoroughly classical, European based designs vs. Japanese influenced ones---or to be more specific, Japanese residential architecture ('shoin', 'sukiya' and 'minka') influenced designs. And it is with the later, such as the Isaac Bell House, the Newport Casino, the Casino at Narragansett Pier, the H. Victor Newcomb Hall (Elberon, NJ), and especially the Samuel Tilton House (Sunnyside Place, Newport, RI), where we find some of their most modern expressions of architectural form.

The text for two of the caption boxes (center bottom and right side middle) have been reproduced below for better legibility.

McKim, Mead and White

The Isaac Bell House and Japan in the Shingle Style (1880's -1900's)

Lecture handout 2015.10.5, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 26

Yasutaka Aoyama

The following text added 2024.6.18:

The above are but a sampling of the Japanese influences seen in McKim, Mead and White, and various other designs could be raised as examples:

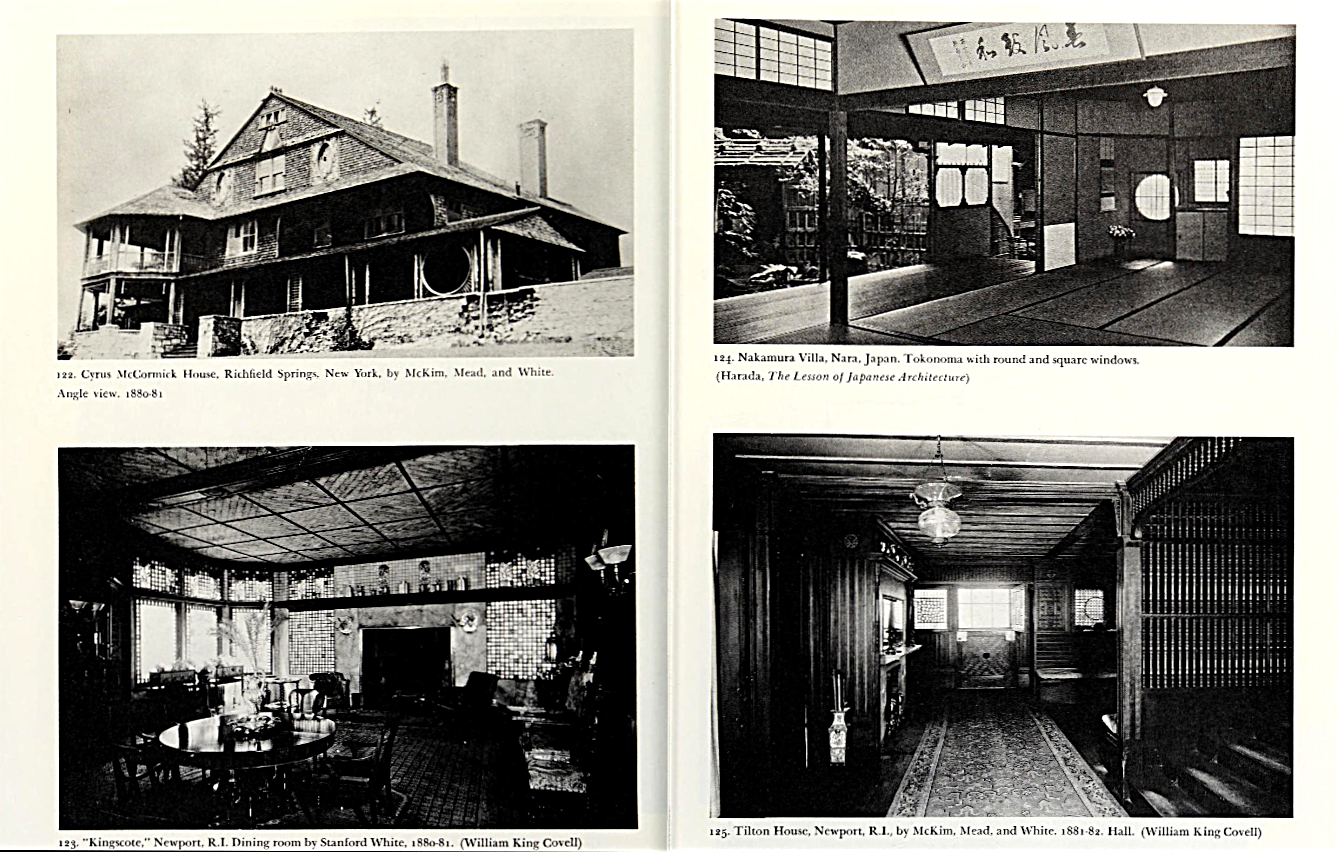

Regarding the "remarkable" Casino at Newport, Rhode Island (1879-81), Vincent Scully writes: "The differentiation in scale here between the framing members and the grilled panels between them recalls Japanese wooden architecture---with the post, the kamoi, and the ramma---and reveals McKim, Mead and White's important amalgamation of influences from that source with indigenous American framing habits. ... It combines a sense of order by no means academic with a variety of experiments in picturesque massing and spatial articulation. More over, it combines Japanese and American stick-style sensitivities with that sweep of design which is typical of the shingle style." (The Shingle Style and Stick Style, revised edition, 1971, pp. 132-133) Even the "experiments in picturesque massing and spatial articulation", as well as the "sweep of design", however, have their precedents in Japanese architecture, which perhaps Scully is not fully aware of.

As for the Victor Newcomb House at Elberon, New Jersey (1880-81), "a building which exhibits qualities more peculiar to McKim, Mead, and White at their original best", we will quote Scully at some length, for it contains some very important observations:

"The hall is paneled in vertical wood siding, with battens, up to door height, where a strip molding passes around the wall. This molding is continuous above the dorrway openings. It is a decorative and nonstructural derivation from the Japanese kamoi, the bracing beam below which the screens slide in a Japanese interior. The space between molding and celing in the Newcomb House is filled by a latticework screen, derived from the Japanese ramma; this creates a continous flow of space, partially screened, between the hall and the other rooms, as well as a constant sense of scale. The Japanese use of the continuous beam or molding with open work above had been clearly described in the American Architect in 1876... As a concession to American living McKim, Mead and White eliminate here the movable screens, but they are obviously experimenting with the continuous frame and open work to give an impression of movability and spatial continuity. ... The elegantly rectangular floor pattern, probably derived from the Japanese mat and looking much like 20th century De Stijl work, also functions to enforce scale and spatial direction. ... The architecture itself is straightforward and decisively interwoven. The ceiling overhead, emphasized by the subtly varied exposed timbers---which are crisscrossed in patterns a little like a Japanese mat system---slides visually through from room to room; the continuity of human scale is kept by the molding. The spaces do not merely open widely into each other they actually penetrate each other; and the whole space thereby expands horizontally with absolute, not relative, continuity. While the toal space thus expands, each unit of space continues to keep its own individuality through the passage of molding and screen. Consequently, space is at once integrated and articulated. This spatial concept, representing a creative assimilation of Japanese influences, appears as a basic principle in the work of Wright; indeed it has been erroneously believed that Wright was the first to achieve it in America." (1971, pp. 134-136).

Concerning the Cyrus McCormick House at Richfield Springs, New York (1881-82), which Scully rates as "their best cottage building in the early 80's" thanks to its "lightness of scale and its creative combination of gable front, porch pavilions, and structural and textural vitality" with "its interwoven basketry of skeletal elements" he says: "Here again there is much of the Japanese and much of the later Wright." And adds that rooms in the house, "are equally distinguished and use delicately scaled details partly colonial, partly Japanese, and wholly proto-Art Nouveau." (p. 137)

From Vincent Scully, The Shingle Style and the Stick Style, Revised Edition (1971), where he includes a photo of the Nakamura Villa of Nara for comparison with various shingle style houses.

Further Examples of the Shingle Style

and

Diversity in Japanese Regional Farmhouse Architecture

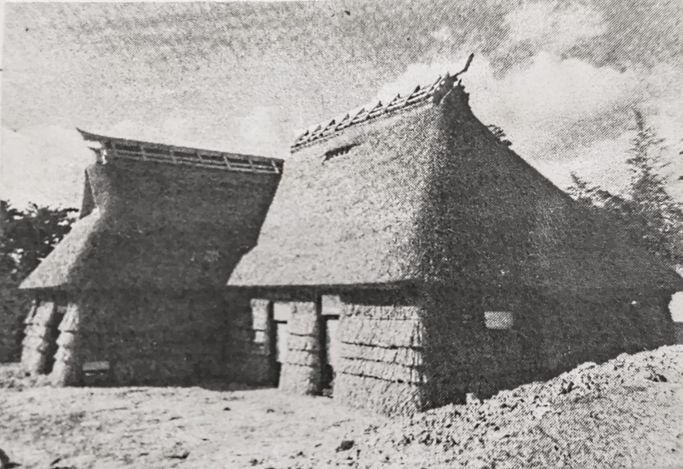

The Japanese influence upon the Shingle Style has been discussed by Vincent Scully in his classic work of the same name; we should add here that within the Japanese influenced exterior elements, not uncommonly the original interiors had rooms also of a Japan-conscious style.

Note below how the shingles of the Stroughton House resemble the overlapping, down to earth effect of the straw-like fiber walls of the Japanese farmhouse, and how the rounded house corners and staggered walls of the latter are also recreated in the former by the roundish turret and house extensions which likewise are made to blend together without sharp corners.

________________________

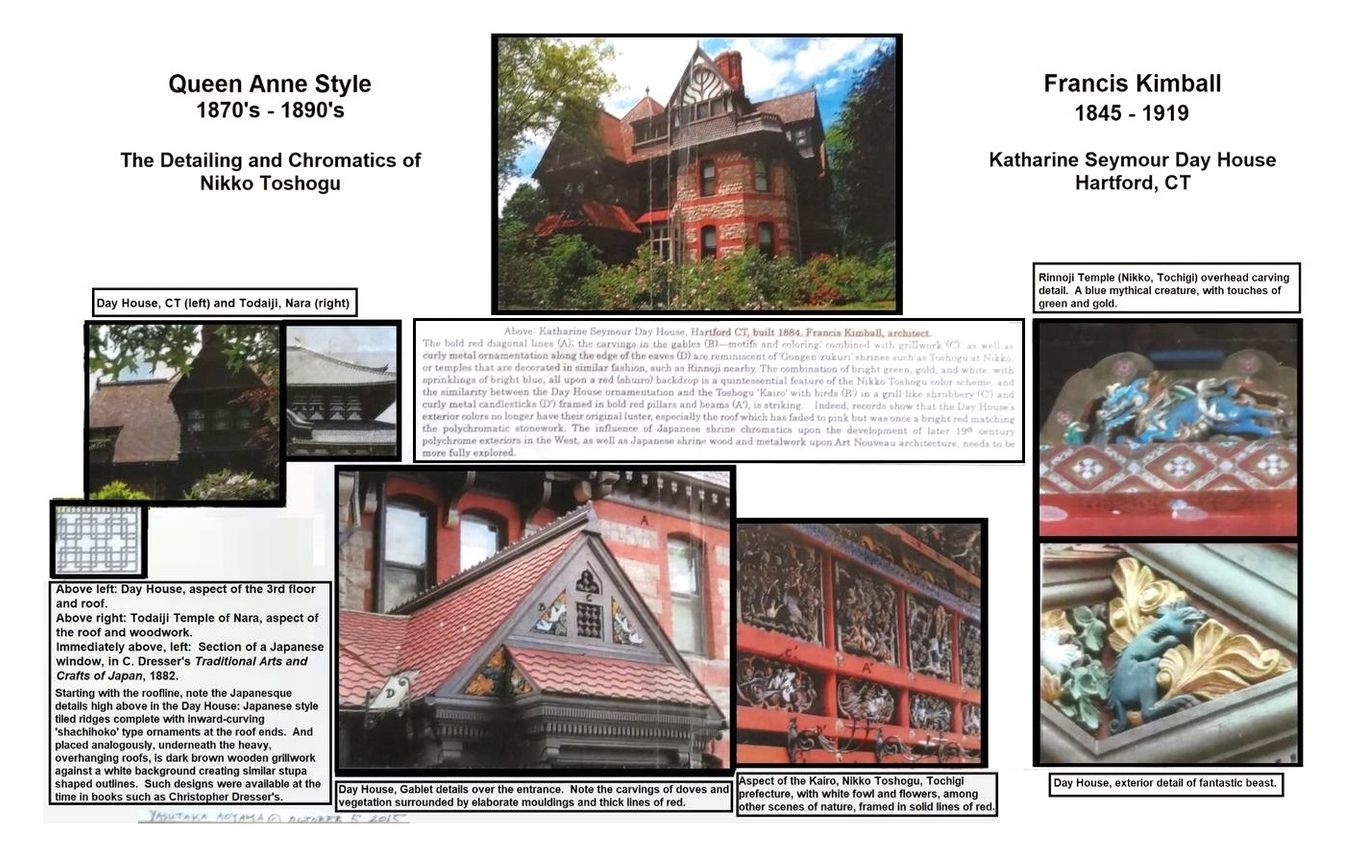

Queen Anne Style in America (1870's to 1890's)

The Japonisme of Unpredictable Complexity and Full-Color Ornateness

Lecture handout 2015.10.5, Architectural Juxtapositions, p.30

Yasutaka Aoyama

"The style of architecture dubbed Queen Anne was Japanesque in a different way. Here the move away from the traditional rectangular box, a standard of Western housing for centuries, was finally taken to its logical extreme. ... Think of the controlled-accident effect in the design of Japanese ceramics or the conspicuous avoidance of repetition in most Japanese arts, and you can see how the Japan idea relates to American Queen Anne architecture. It is especially apparent in the work of the architect Stanford White and the firm of Peabody and Stearns. The Opera House built in Norfolk, Connecticut, in 1883 and the Goodwin Building, a mix-use office and apartment complex built for Francis and James Goodwin in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1881... are rich in Japaneseque detail. ... The Japan craze affected the look of rural villages throughout New England through the growing popularity of new architectural forms, such as libraries, opera houses, and town halls."

William Hosley, The Japan Idea: Art and Life in Victorian America (1990, p. 105)

The Queen Anne style in the United States is often characterized as an eclectic mix of cultural styles--which it is, and the Japanese element is blended into that mix so that it often goes unrecognized. But many of the features of the style--the bold exterior coloring, the ornamental pattern details, the prominent roofs and complex intersecting rooflines, the asymmetric floor plans, the bay windows and other protrusions from the exterior wall surface--are prominent features of Japanese architecture. Of particular importance in the Queen Anne style seems to be Japanese shrine architecture, such as the Nikko Toshogu shrine-masoleum, dedicated to the Tokugawa Shogun Ieyasu, in Tochigi, Japan. Nikko was an extremely popular site for western tourists and visiting artists in the late 19th century, and many praises and depictions of it followed. It has not however, been sufficiently recognized as an inspiration for the Queen Anne style in discussions of Japonisme.

It is certainly at least possible that it did have an influence upon the Queen Anne style; there is no question that Japanese architecture in general did, as Vincent Scully, in his classic The Shingle Style and the Stick Style, wrote, regarding the formation of the Queen Anne style and the general direction of American architecture in the late 19th century: "other sources of inspiration and direction also began to be explored; Japanese architecture, for instance, had an important influence." (revised edition, Yale University Press, 1971, p. 4)

Below is an example of that influence in the work of the architect Francis Kimball.

Regarding these kinds of carved or plaster moulded exteror decorations and panel work, Vincent Scully writes: "Queen Anne shingles, panel work, and open interior space were reinforced by the architectural influence of another country represented by wooden buildings at the Centennial: that is, Japan. The Japanese buildings, a 'Bazaar' and a 'Dwelling' were of frame construction with overhanging eaves, and their structural articulation in some ways recalled the American stick style. The American Architect wrote of the 'Dwelling,' 'A bird is handsomely carve in bas-relief on the wooden panel between the top of the front door and the overhanging porch.' This feature relates to Queen Anne decorative motifs, as, for example, to its carved barge boards and plaster panels." (The Shingle Style and the Stick Style, Revised Edition, 1971, p. 21)

Here we have focused upon the ornamental aspects of the Queen Anne style; we must add as a concluding note that this does not preclude other fundamental Japanese influences.

That influence extended to Queen Anne interiors, and is more apparent in contemporary writings of the 19th century. Take George Sheldon's description in his Artistic Country Seats---Types of Recent American Villa and Cottage Architecture (1886) of the Millbank House at Greenich, Connecticut, designed by architects Lamb and Rich---whose other designs, by the way, also exhibit Japanesque qualities: "The parlor, twenty by forty-four feet, is in Japanese style, in a deep-red lacquer, with a bamboo ceiling, and walls covered with Japanese embroidery. A semicircular bay-window is at one end of the room and an octagonal at the other. Standing at the mantel, which faces the entrance to the hall and is Japanese in spirit, you look across the parlor, across the hall, across the library, and across the dining-room, out of the latter's bay-window, and on to the lawn---an unusually extensive view." (p. 65)

This leads us to an even more critical point: the influence of the Japanese free and flexible floor plan. As Scully comments on this topic, "More importantly, of Japanese interior spatial organization, the Architect stated: 'Thus at any moment any partition can be taken down, and two or more rooms, or the whole house, be thrown into one large apartment, broken only by the posts which marked the corners of the rooms. Doors and windows, as we use them, there are none.' Consequently, Queen Anne materials and general spatial direction received, by 1876, the support of influences from similar aspects of Japanese domestic architecture. These had already been allied, through comparable---though in Japanese hands more sensitive and integral---handling of the wooden frame, to the American stick style itself." (1971, p. 22)

________________________

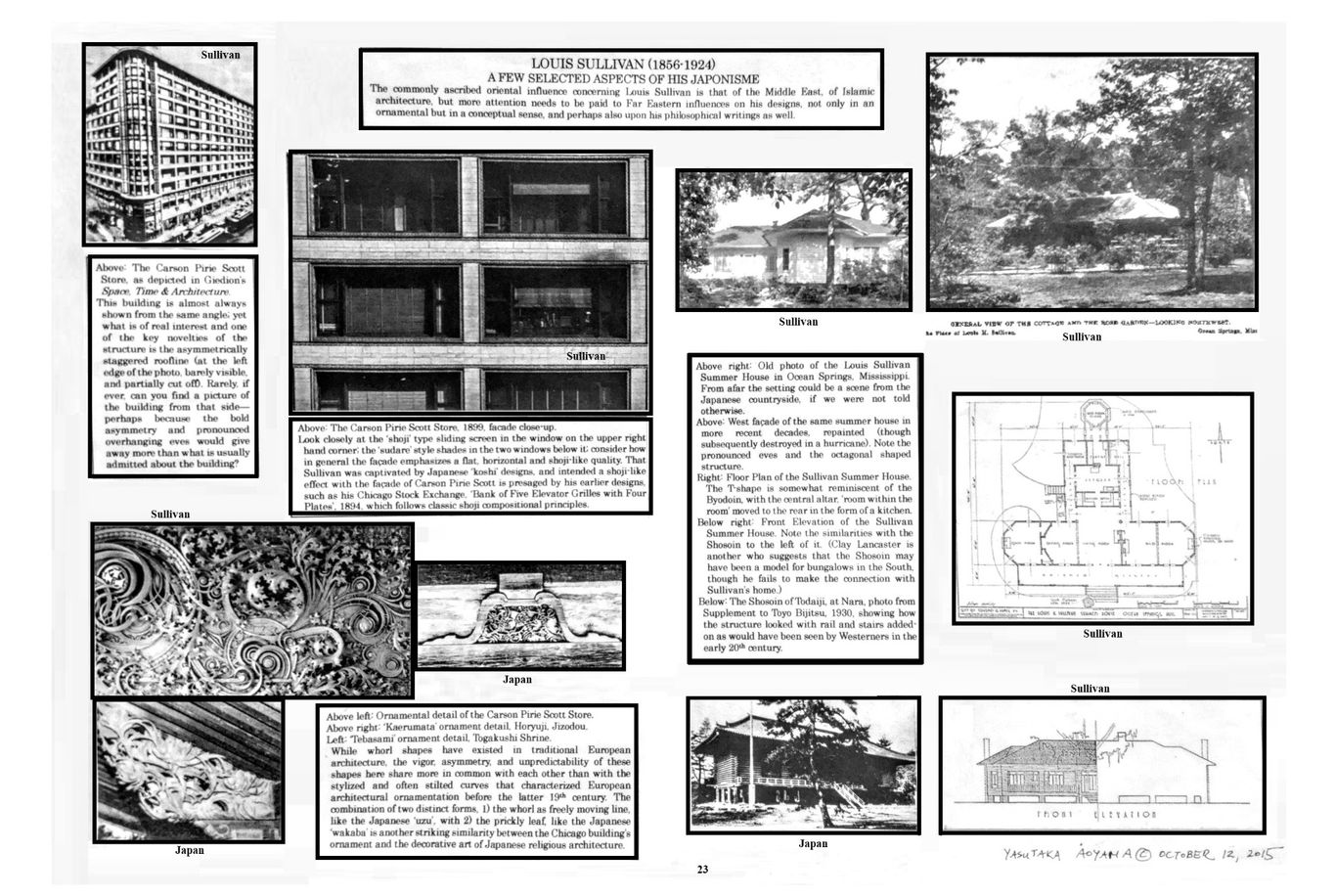

Louis Sullivan (1856-1924)

Selected Aspects of his Japonisme:

Perhaps more Japanese than Islamic in Style

Lecture handout 2015.10.12, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 28

Yasutaka Aoyama

There are definitely Islamic decorative elements in Louis Sullivan's designs, such as his National Farmers Bank (Owatonna, MI) interior, or his Garrick Theater (Chicago, IL) or his Prudential Building (Buffalo, NY) exteriors, among other works, as pointed out by biographers and architectural historians in terms of geometry, color, motif, and level of intricacy. But a key characteristic of most Islamic art, even floral art, is symmetry and a sense of perfect balance. However there are less tame and more wildly asymmetric lines in Sullivan's designs, and also a great amount of near full sculptural relief, that is alien to the Islamic tradition and much closer in spirit to the type of ornate Shinto religious architecture (with carvings by master sculptors such as Ishikawa Uncho), that was to be found flourishing in every region of Japan from the 18th century onward.

Therefore, given his blend of Islamic and Japanese aesthetic qualities, his ornamental style, might be described as 'Islamo-Japanese', though leaning more heavily toward the Japanese in form and spirit. That Sullivan was interested in Japanese design is testified by the fact that he had several books on Japan and Japanese art, and that furthermore, he occasionally asked Frank Lloyd Wright, who worked for him, to bid at auctions on his behalf for Japanese art objects (Sullivan bio by Yamabana Nami, in Katagami Style, 2012, edited by Mitsubishi Ichigokan Museum et. al., supervised by Mabuchi A, et. al.)

A few further comparisons between Sullivan's designs and those of Japan (and China) follow the lecture handout immediately below.

Below: Japanese shrine and festival wagon carvings compared with exterior detail of Sullivan Center, Chicago (center)

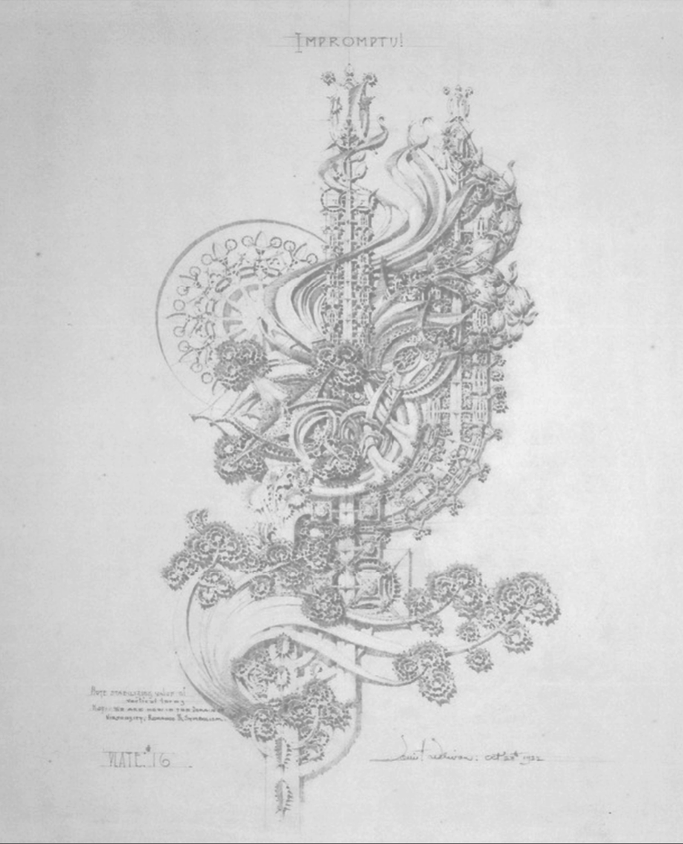

Below left: Louis Sullivan sketch 16 of 'Impromptu' (1922). Right: Japanese eave carvings (19th century)

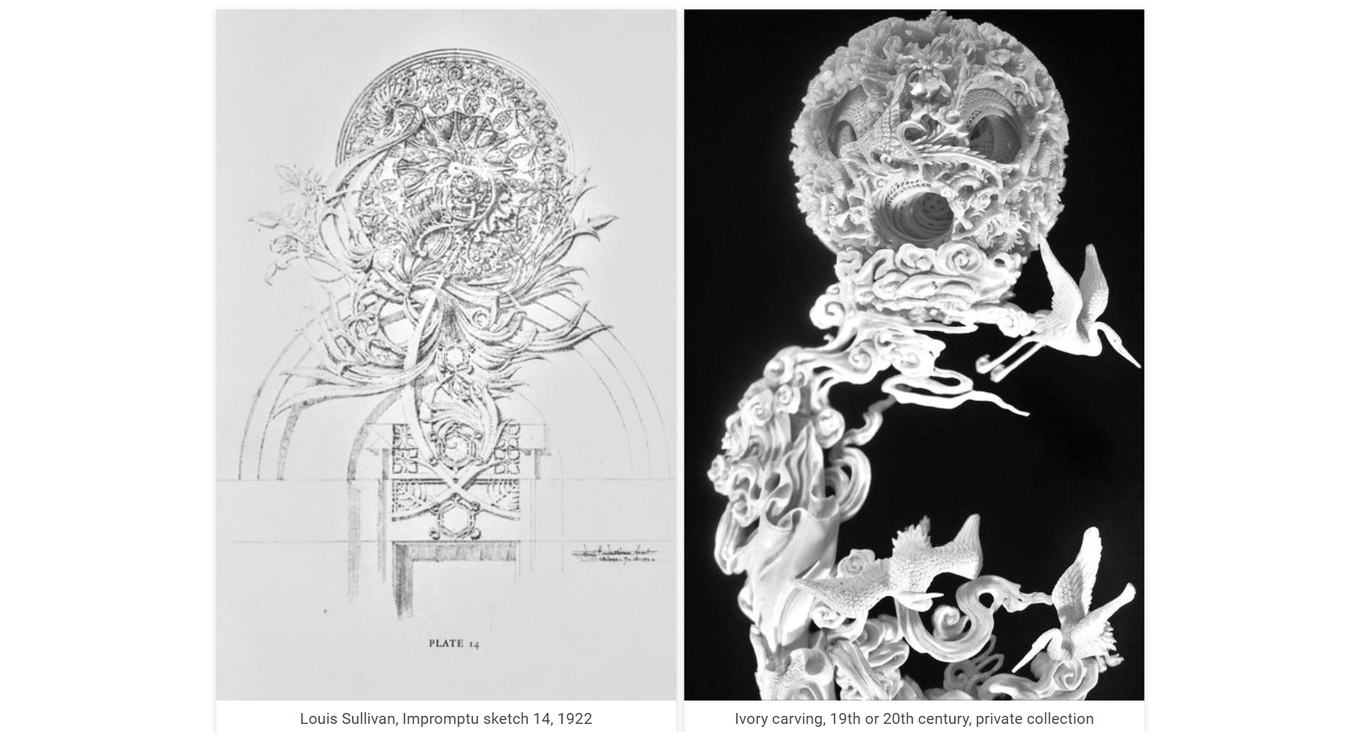

Below left: Louis Sullivan sketch 14 from 'Impromptu'. Right: Chinese style ivory carving, Japanese private collection, 19th or 20th century. Done in a style well developed by the mid 19th century, these intricate balls are known as a form of Chinese craftsmanship, but numerous pieces of the most elaborate kind are held in Japanese collections. Those at the National Palace Museum of Taiwan are the best known.

________________________

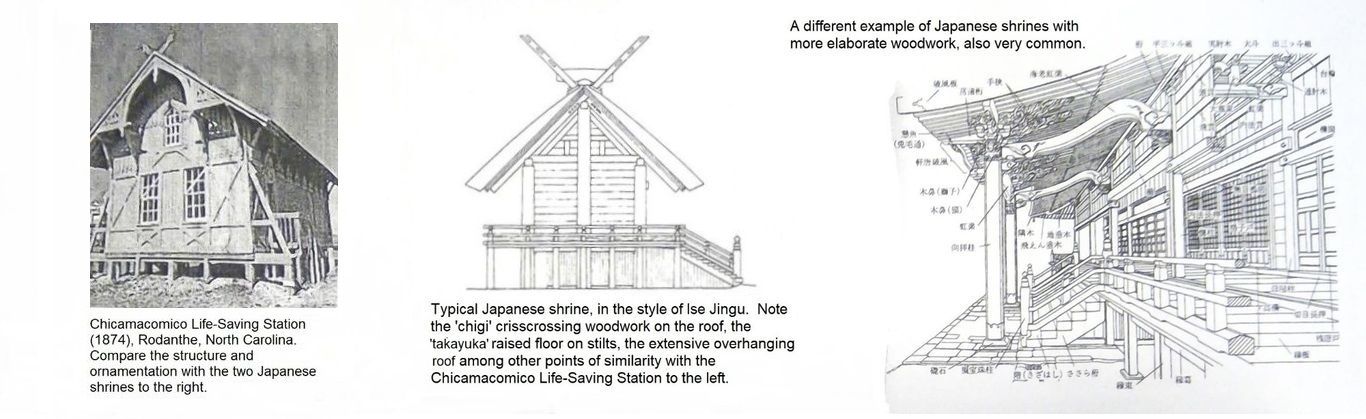

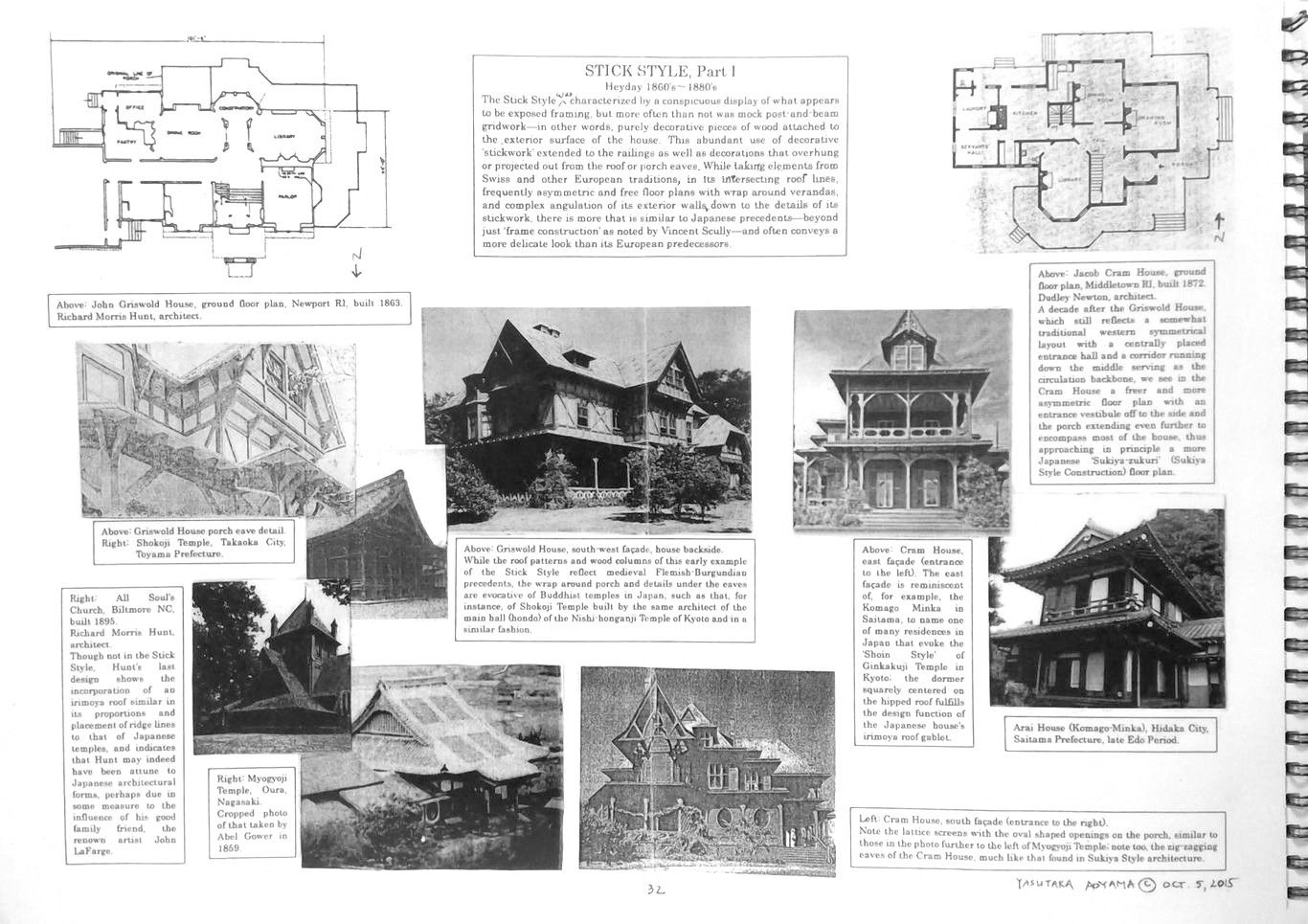

Stick Style, Part I

Incorporating Japanese Jinja (Shrine) Woodwork in American Style

Lecture handout 2015.10.5, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 32

Yasutaka Aoyama

"The Japanese pavilion in Philadelphia (at the 1876 Centennial Exposition) helped to stimulate a popular craze for things Japanese... At a deeper level its influence soon appeared in the American house in a predilection for the open plan, latticework, extended eaves, a craftsmanlike assembly of parts, and the integration of the building with its landscaped setting ... "

Frederick Koeper, American Architecture, Vol. 2: 1860 to 1976, MIT Press, 1983.

"Japanese influence in Victorian American architecture is demonstrated in the content of specific styles and in subordinate ornament, both inside and out. Most of all it was communicated through moveable furnishings and wall and window treatments, without which the architecture appears barren and confusing. One of the most intriguing arguments in favor of Japanese influence in American architecture is Scully's stick style, the most radical, modern, and explicitly American of the reform styles."

William Hosley, The Japan Idea: Art and LIfe in Victorian America, Wadsworth Atheneum, 1990.

Uploaded 2024.6.19

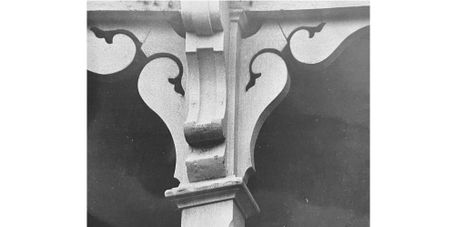

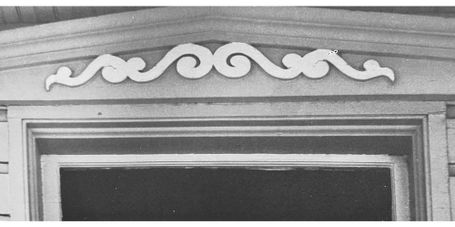

Japanese Motifs in Stick Style Ornament

The following photos of stick style ornament are from Ben Karp's Wood Motifs in American Domestic Architecture (1966), of exteriors dating from 1850-1900, from primarily the east coast of the United States, centered on New York State, though examples can be found across the United States. As Vincent Scully, one of the foremost authorities on the Stick Style wrote, ''the builders of the stick style broke with the grand styles of the past and absorbed influences from the comparable wooden styles of Switzerland and Japan.'' (The Shingle Style and the Stick Style, Revised Edition, 1971, p. 3)

True, Switzerland was a factor; but a look at the fine details of the more distinctive design characteristics of American stickwork points to the influence of Japan. Just as Japanese ukiyo-e awakened English artists and artisans to find comparable inspirational sources in gothic traditions closer to home but nevertheless mirroring Japanese designs and taste, so too, did American architects claim precedents in Swiss architecture, while in fact often incorporating specific patterns and decorative conceptions from Japan.

Text be added and individual photos to be captioned.

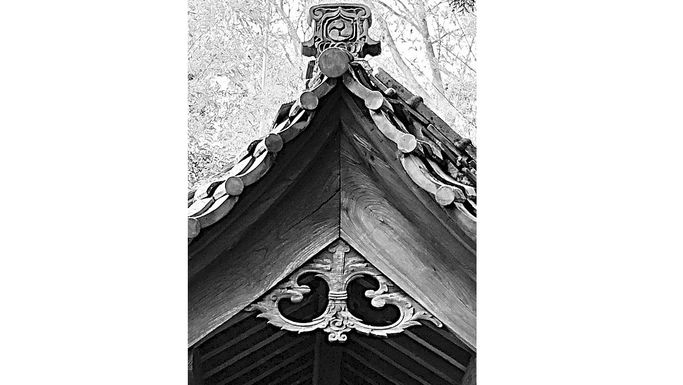

The Uzu and Wakaba Motif in the Stick Style

Examples of the Uzu Wakaba Motif in Japanese Shrine Eaves and Archways

Juxtapositions of the Stick Style and the Japanese Uzu Wakaba Motif

Stick Style Ranma-type Woodwork

Stick Style and Japanese Gegyo-type Gable Ornaments

Stick Style Design Elements from Japanese Temple/Palace Doorways to Eaves

The stick style reproduced various Japanese architectural forms freely on its exteriors; even gates and doors might be replicated on the facade of a building as in the example below left. The Daitokuji Temple karahafu-roofed mon (gate) is shown to the right for comparison. Sometimes there is a chrysanthemum emblem in the center panel of the temple gate doors, corresponding to the roundrel on the stick style facade, though not on the Daitokuji gate doors shown here. Nevertheless, the similarity is still quite apparent. The stick style facade includes other details of mon doors, such as the 'I' bar bracing boards situated between the three panels on each side.

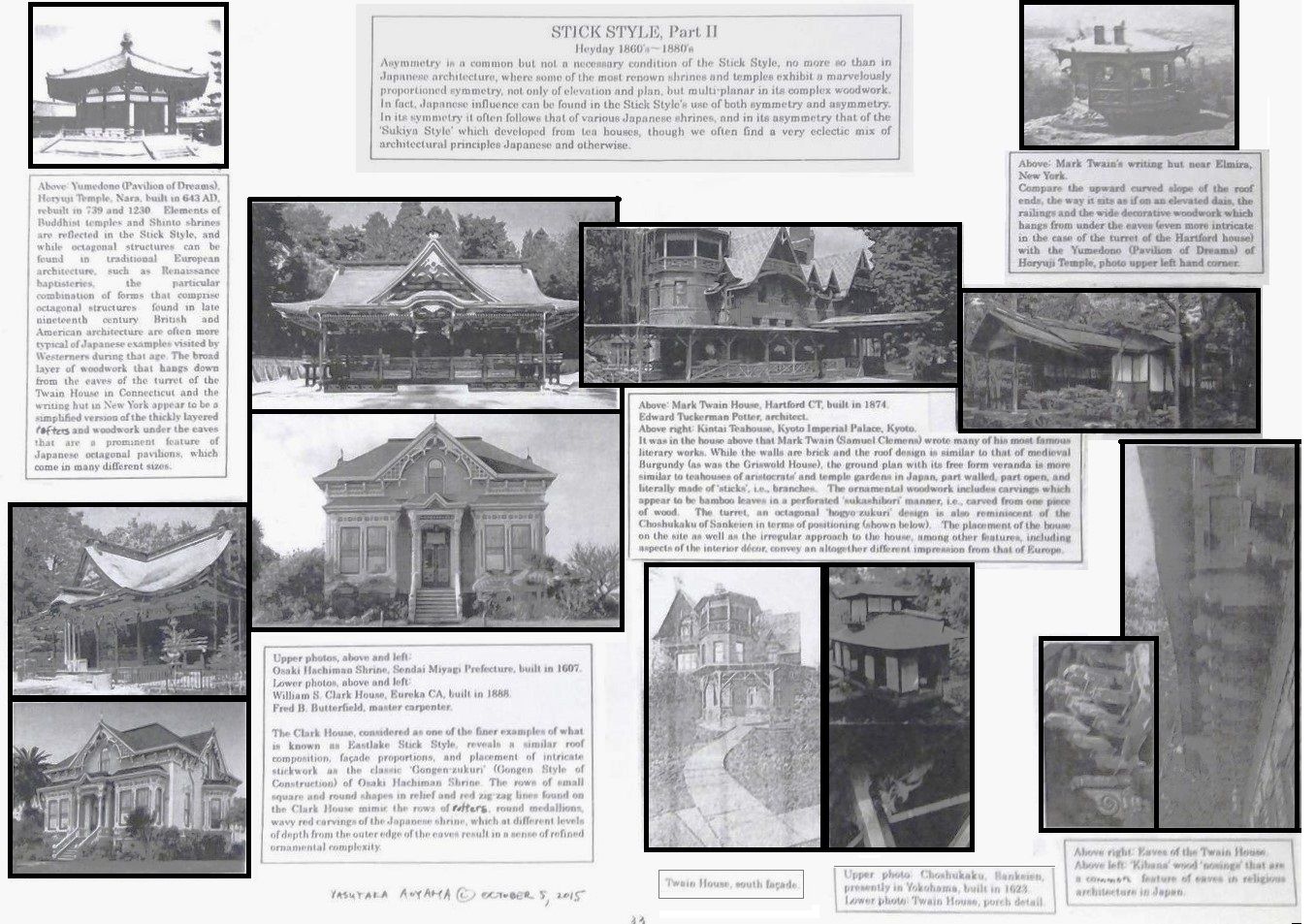

Stick Style, Part II

Incorporating Japanese Style Symmetry and Asymmetry into American Design

Lecture handout 2015.10.5, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 33

Asymmetry is a common but not a necessary condition of the Stick Style, no more so than in Japanese architecture, where some of the most renown shrines and temples exhibit a marvelously proportioned symmetry, not only of elevation and plan, but multiplanar in its complex woodwork. In fact Japanese influence can be found in the Stick Style's use of both symmetry and asymmetry. In its symmetry it often follows that of various Japanese shrines, and in its asymmetry that of the 'Sukiya Style' which evolved from tea houses; though we frequently find a very eclectic mix of architectural principles, Japanese and otherwise in Stick Style designs.

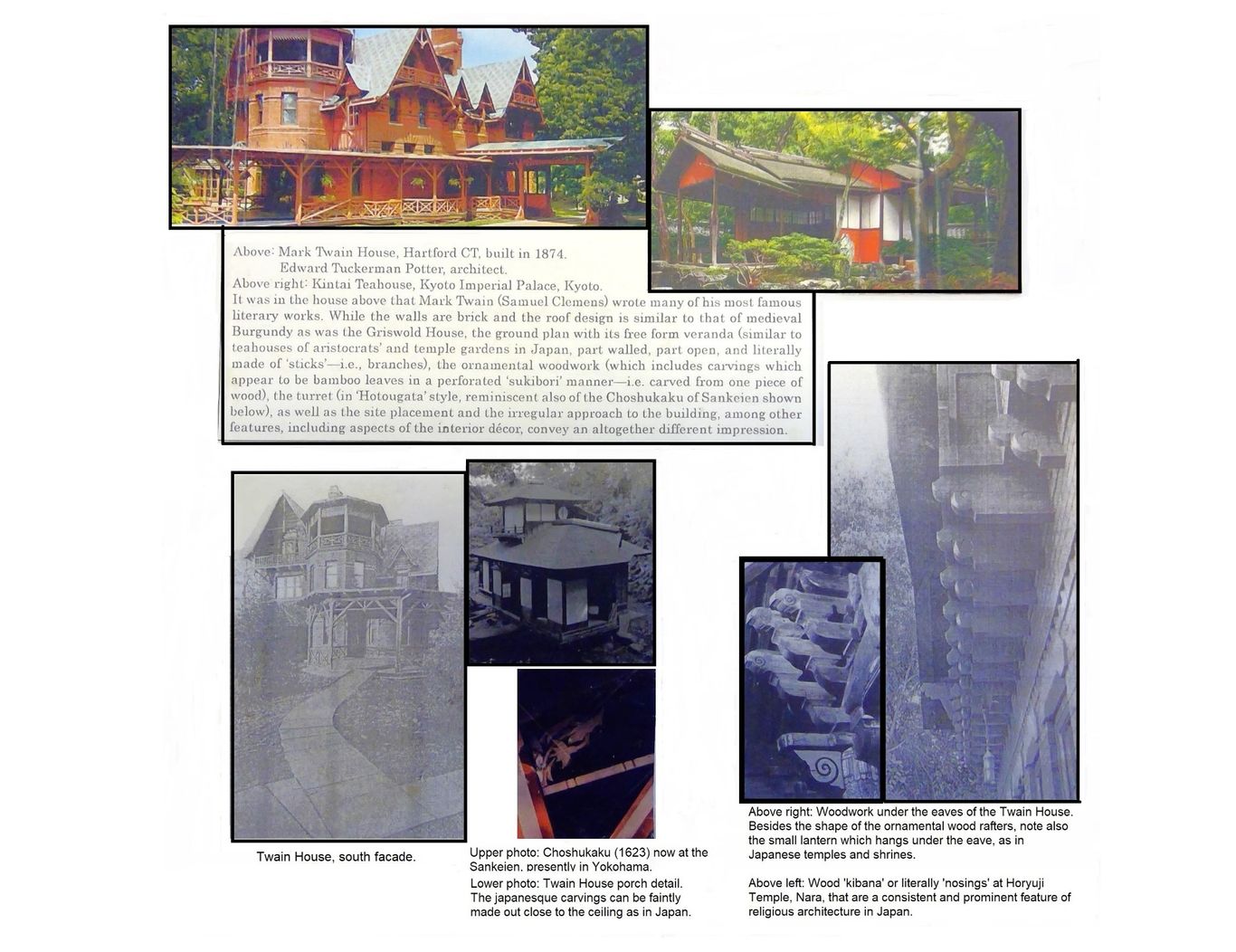

Sections on Mark Twain from Stick Style, Part II

Twain House Eave Details

Low sloped, extended eaves with taruki-like boards, ranma-like woodwork on wide open engawa or tsukimi type porches.

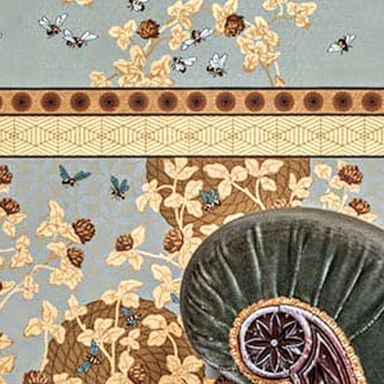

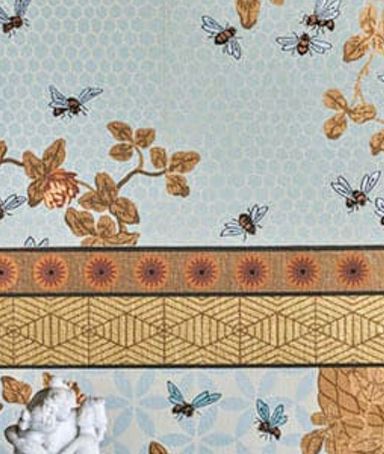

Katagami Patterns and Traditional Japanese Motifs throughout the Twain House

Restoration of the original wallpaper clearly shows the Japanesque influence in the decorative approach at the Twain House.

Japonaiserie objects scattered throughout the Twain House

Typical mid-19th century style Japanese cloisonné and wallpaper designs as well as Japanese temple-reminiscent carvings of the fireplace mantle, blend with classical figures, paintings and books.

Japonaiserie in the Indoor Garden/Greenhouse of the Twain House

Note in this old photo how numerous oriental objects some Japanese and others possibly Chinese, were nonchalantly placed here and there in a very eclectic style: Japanese chochin lanterns above, and a frog on the rim of the indoor pond below, porcelains in cabinets and on a Chinese style displaying stand, mixed with classical Greco-Roman style sculptures. Among the indoor plants, it looks as if there are some of Japanese origin, such as the morning glory (朝顔)and aspidistra (ハラン). Alongside the japonisme of Japanese visual and plastic arts, was a well-documented interest and importation of Japanese plant varieties and gardening ideas, including philosophical / poetic concepts associated with them. See for instance, Hashimoto Yorimitsu, 'Asagao wo meguru eigoken no japonisumu---gadeningu kara zen made' [The japonisme of the morning glory in anglophone countries---from gardening to Zen] in The Japonisme Association edited Japonisme Reconsidered: The Other and the Self in Representations of Japanese Culture, Tokyo: Shibunkaku Publishing, 2022.

This caption uploaded 2024/3/17.

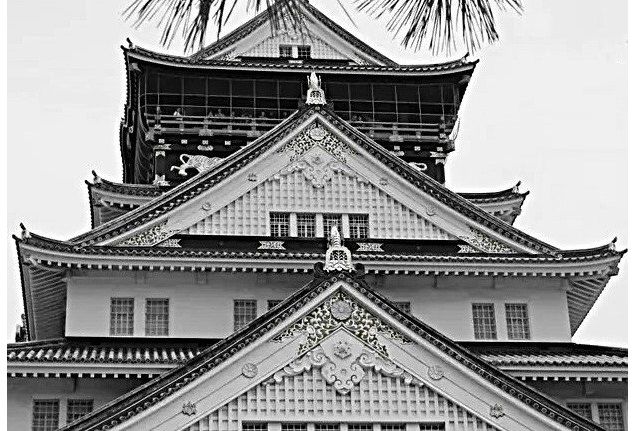

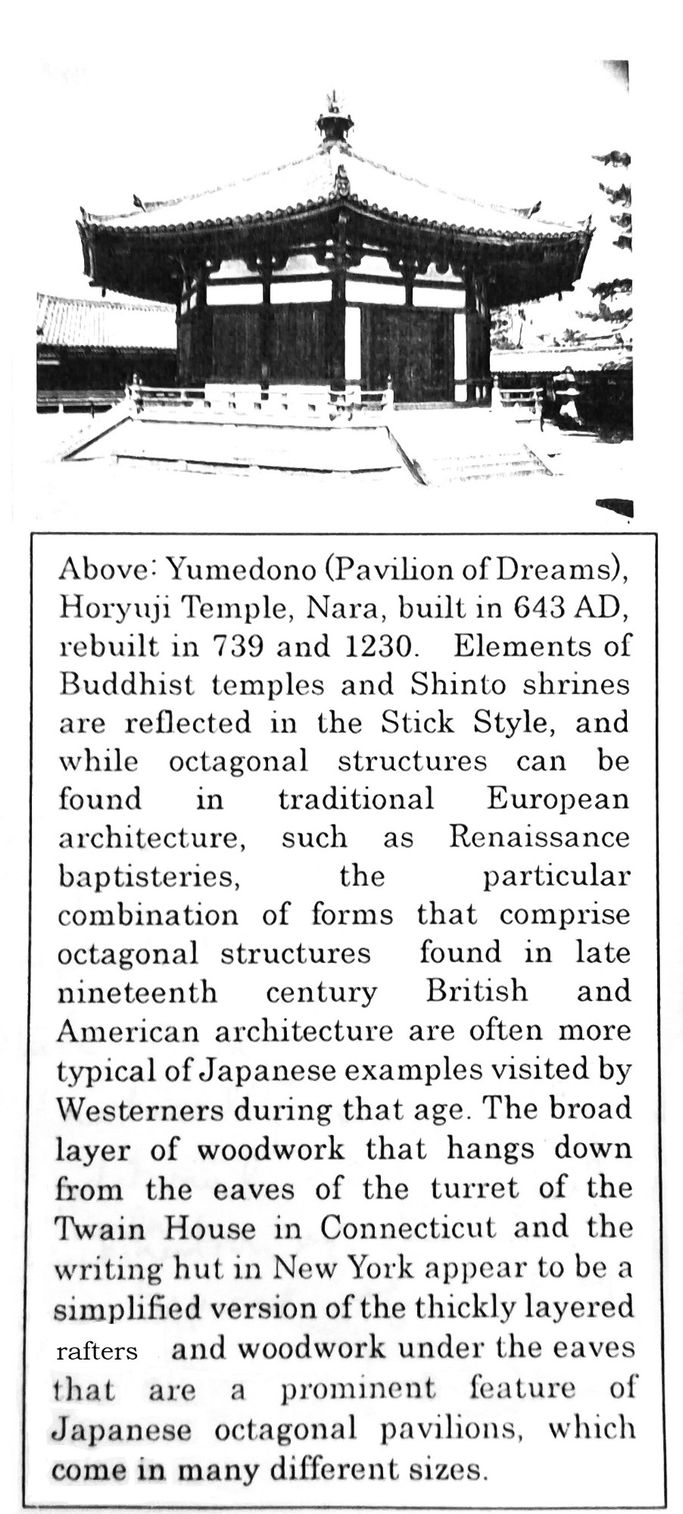

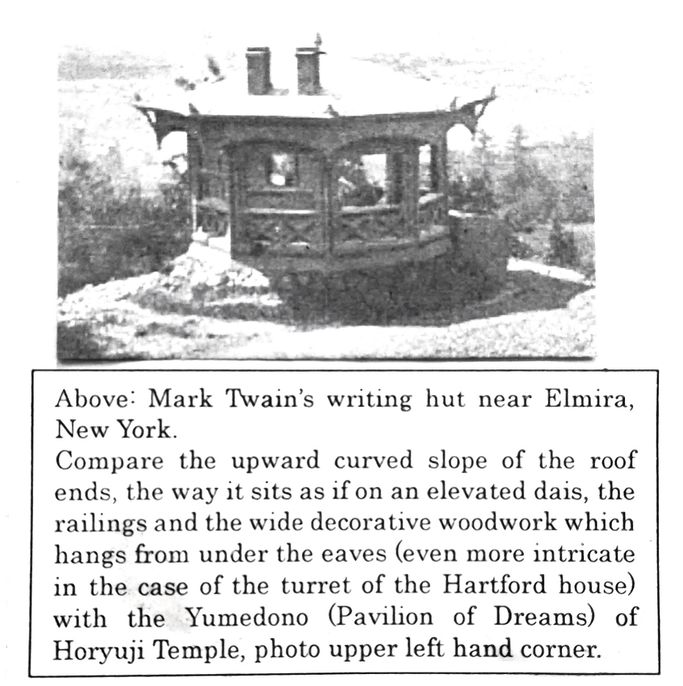

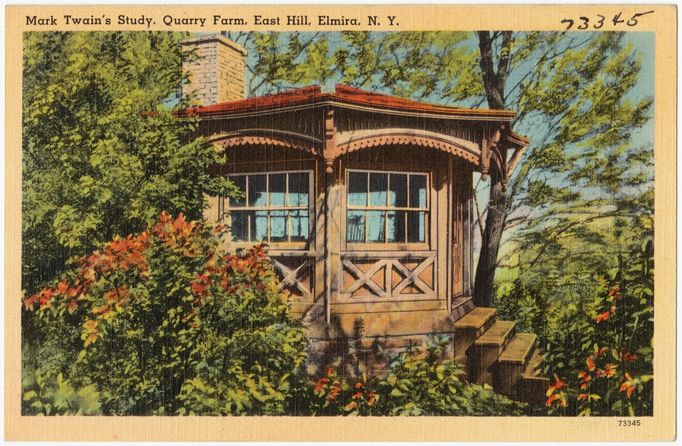

The Yumedono of Horyuji Temple, Nara, and Twain's writing hut in Elmira, New York

The top and middle (postcard) photos on the right show the hut in its original location on Quarry Farm in Elmira, New York, with splendid views of the surrounding countryside. The last photo shows it in its present location on the campus of Elmira College in Elmira, New York.

________________________

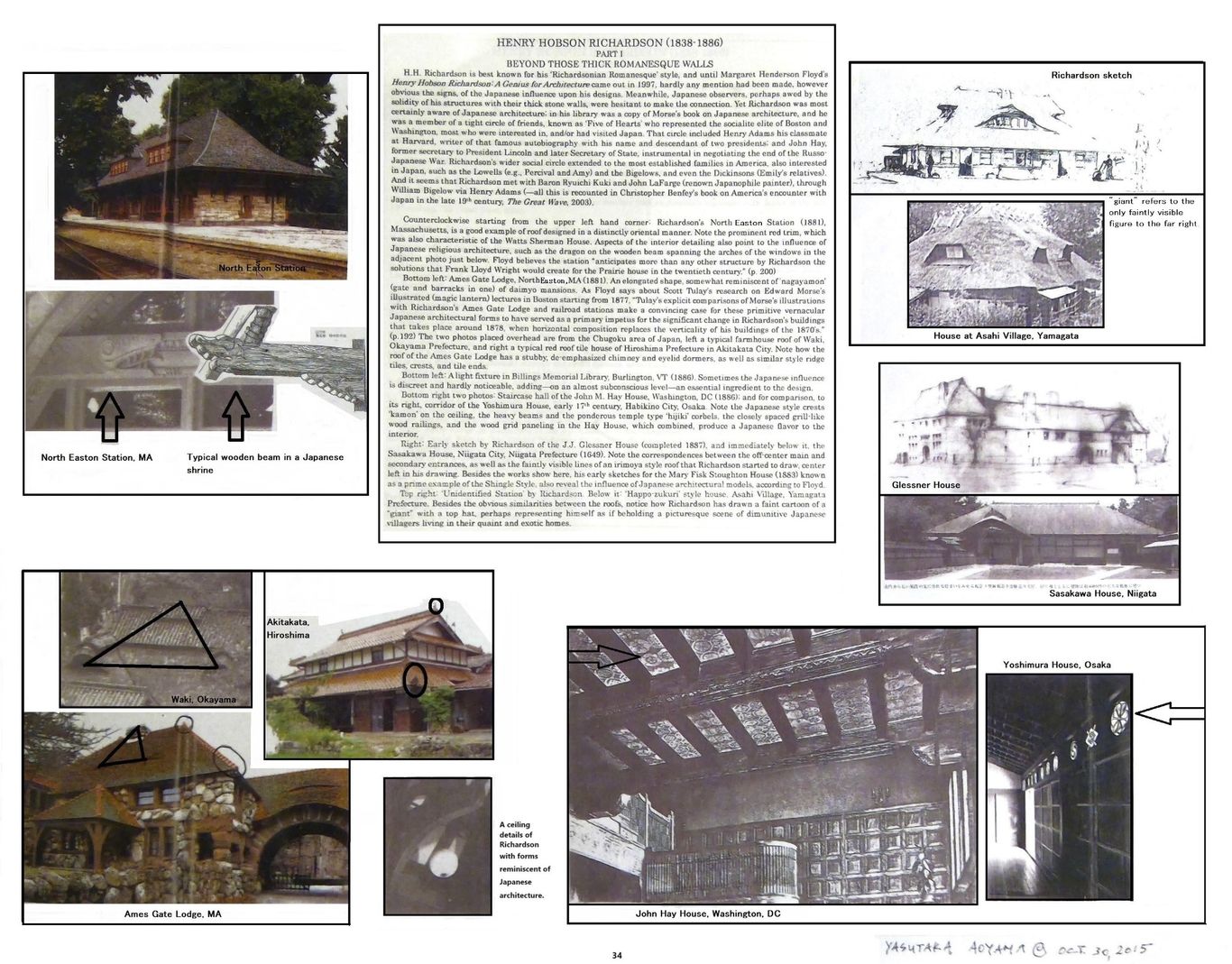

Henry Hobson Richardson (1838-1886)

Part I: Beyond those Thick Romanesque Walls

Lecture handout 2015.11.5, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 34

Yasutaka Aoyama

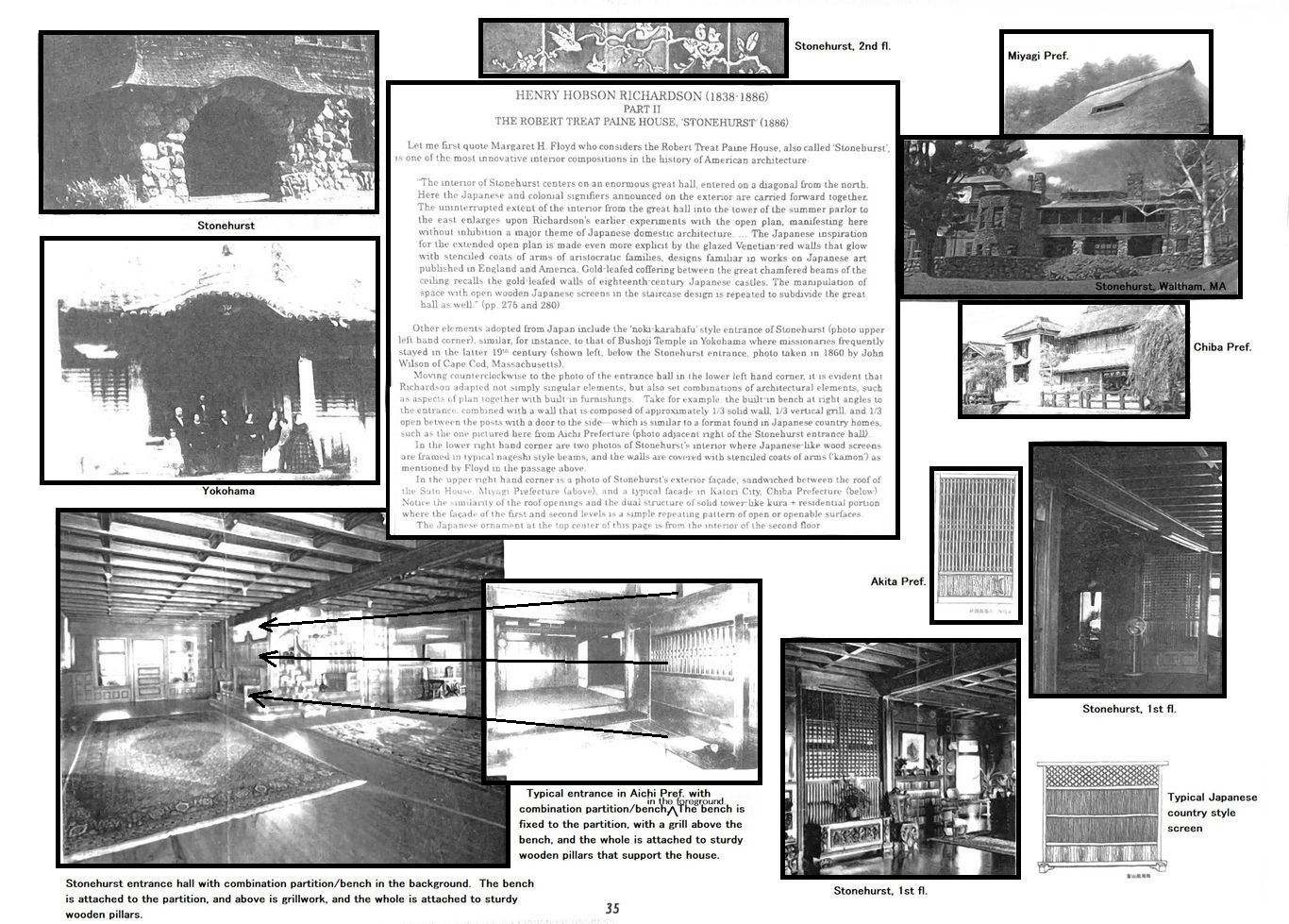

Henry Hobson Richardson, Part II

The Robert Treat Paine House, 'Stonehurst' (Waltham, MA)

Lecture handout 2015.11.5, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 35

________________________

Uploaded 2023/5/5, under construction

Peabody and Stearns

Shingle Style 'Castles' and Byobu Painted 'Castles in the Sky'

Kragsyde vs. Jurakudai

Probing the Possible Sources of Architectural Whimsy in Japanese Castle Design

With Additional Examples from W. R. Emerson, Lamb and Rich, and John Rex

Yasutaka Aoyama

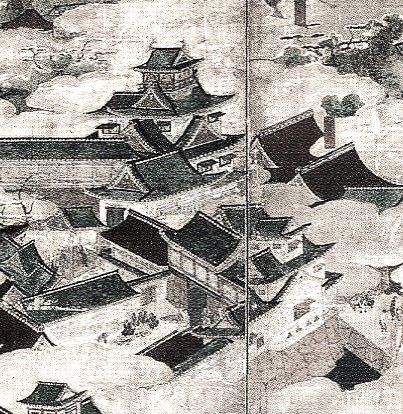

Idyllic Japanese farmhouses were probably not the only Japanese inspiration for the American Shingle Style. A fine comb comparison of Peabody and Stearns' 'Kragsyde' mansion (1883-1885) with byobu screen depictions of the 'Jurakudai' palace/castle of 16th century Osaka reveals intriguing correspondences adds spice to our appreciation of architectonics across space and time.

Besides the Isaac Bell House by McKim, Mead, and White and the Mary Fiske Stoughton House by H. H. Richardson, Kragsyde, by Peabody and Stearns (the leading architectural firm of its day alongside the aforementioned), is one of the most well-known examples of what Vincent Scully of Yale University coined 'The Shingle Style'. The growing freedom of plans and sometimes exaggerated asymmetry not only in plan but in elevation, with offset entrances, wide covered porches or walkways ('engawa' or 'fukinuki roka') was a continuation of a process that started with Stick Style homes, also influenced by Japanese architecture. And once again, as in the Isaac Bell House, we find the use of paired sliding doors ('hikido') which when retracted allow the rooms to become unified llarger spaces following the age old principle of entertaining in Japanese reception rooms ('zashiki'). In the case of Kragsyde, the abundant parallels in terms of conceptions and detail with Toyotomi Hideyoshi's 'Jurakudai', a combination of palace and castle, makes for great food for thought.

Robert S. Peabody, of Peabody and Stearns, once read what Vincent Scully called "a revealing paper" at the Boston Society of Architects entitled 'A Talk about Queen Anne’ but which was really meant to be about the broader movement of American architecture at the time. The paper ends with a paragraph of which we will quote the first sentence: "Thus I have meant to show that this movement is very strong and well established in England, and consequently of importance to our designers; that bric-a-brac, and Japan, and India, and classic mythology, and odds and ends, inspire it quite as much as Queen Anne; and that after all it is a curious support to our American eclectic notions." (in The Shingle Style and the Stick Style, revised edition, 1971, p. 42). Scully's footnote regarding this statement starts with: "The 'Japanese' reference is also important, as indicated earlier."

Among the various architectural sources of Peabody and Stearns, it is the Japanese element which Scully singles out for re-emphasis. For while India (not without reason 'the crown jewel of the British Empire'), was of influence in England, as seen in Brighton Pavilion, Japan loomed larger in the American architectural imagination, the land which America was the most instrumental in opening to Western nations. As for 'classic mythology', of course familiar, and thus lacking in stimulative power as a novel design source, except in combination with other things different. And 'bric-a-brac' was simply a catch-all phrase for a miscellaneous array of ornamentation, like 'odds and ends' which supplied little in terms of motivating inspiration; it was a term to characterize the look of things after they had been completed, rather than a wellspring source of design ideas.

It was thus Japan in particular that provided a truely new aesthetic ideal in architecture, as it did for the rest of the arts at the time. And in the case of Kragsyde, that impression is not limited just to the 1) Japanesque helter-skelter of intersecting roof lines or 2) the general 'bending' of the plan, but also 3) the large diagonally placed 'double-decker' roofed bridge-like feature on a solid stone wall formation; 4) the existence of another extending, but more lighter raised walkway, at an off-angle to the more ponderous arched edifice, with also 5) a major and minor protruding bays situated in-between the two bridge-like extensions; as well as various minor details, such as 6) the castle window shutters jutting straight out above the windows; ---all are repeated with similar effect to a Japanese castle by somewhat different means in Kragsyde---excepting (speaking only somewhat tongue in cheek) 7) Kragsyde's 'tenshukaku' or high tower, while also rimed with a balcony, takes a polygonal, rather rectangular form.

For perspective on this idea, it may be of help to compare Kragsyde with other American houses with Japanese castle-like designs of the same period.

Perhaps closest to Kragsyde in many respects of plan, elevation, construction material, and site, is William Ralph Emerson's W. B. Howard House (1883-84) on Mount Desert, an island in the state of Maine. As Scully describes it, "High on one of the wooded hills of that island, it echoed with its light, shingled masses and pointed gables the forms of the mountains and pine trees around it. Eminently pictorial, it was a 19th-century romantic landscape painter's ideal of an upland dwelling, perched lightly above misty valleys, its rough texture and warm colors in harmony with the colors and textures of its terrain. ... As many of the best houses under consideration, there was a great sense of openness to the vista, of a plunge into the voids of space. In this the Howard House is similar to Peabody and Stearns' Kragsyde, but looser, less Richardsonian. It is playful in such features as the porch above the billiard room section, covered by an open gable roof supported on shingled piers and with lattice work in the open gable. The undercurrent of influence from Japanese frame construction, which had been present ever since the midcentury, gave this porch a vaguely Oriental aspect." (The Shingle Style and the Stick Style, Revised Edition, 1971, pp. 110-111) The Howard House also shares with Kragsyde the Japanese castle-like qualities in its 'stacking' of structures of different shape one on top of the other at different angles, on a base of stone; and the open gable roof with its lattice work plays the counterpart to a tenshukaku.

Just to mention one more example, Lamb and Rich's House at Navesink Park, NJ (1882) is also reminiscent of Japanese castle architecture, with its solid, sloping stone base and gables of different sizes facing in various directions and its extensive, outward extending porchways and extensive latticework. Japanese castles were also distinguished by extremely solid, sloping stone bases upon which more delicate structures were built, unlike traditional European castles where stonework of similar nature rose from bottom to top. Most castles in Japan had free plan, sprawling wooden palaces on the massive stone platform as well plastered keeps with grilled windows and latticework, crowned by a relatively small tenshukaku.

Text to be added.

John Rex (with unidentified Japanese architect), Wyle House, Madera County, CA, 1961

"The Modernist design of the house, tinged with a Japanese-esque influence possibly from one of John Rex's draftsmen, features expansive floor-to-ceiling windows and a distinctive umbrella-shaped roof." (Open Space, 'Mid-Century Modern Glass House on a 3,000-Acre Ranch | House Tour', Premiered Jan 18, 2024, Youtube). While cut off in this image, the Japanese castle style curving of the stone wall can still be made out on the extreme right. Even without it, the stacking of irregular stonework, the use of it as a platform for a structure with extending eaves gives it a recognizably Japanese look. The stone sculpture to the left in the foreground is also reminiscent of stone monuments placed on castle grounds; also cut off from view to the left are more rock formations recalling zen rock gardens. There is much about the interior which also echoes Japanese architecture, such as the exposed wood framing of the ceiling combined with round chochin like lamps, for example.

Text to be added.

Undelivered Lectures and Material for Architectural Juxtapositions II continued in Architectural Japonisme II - VIII.