________________________

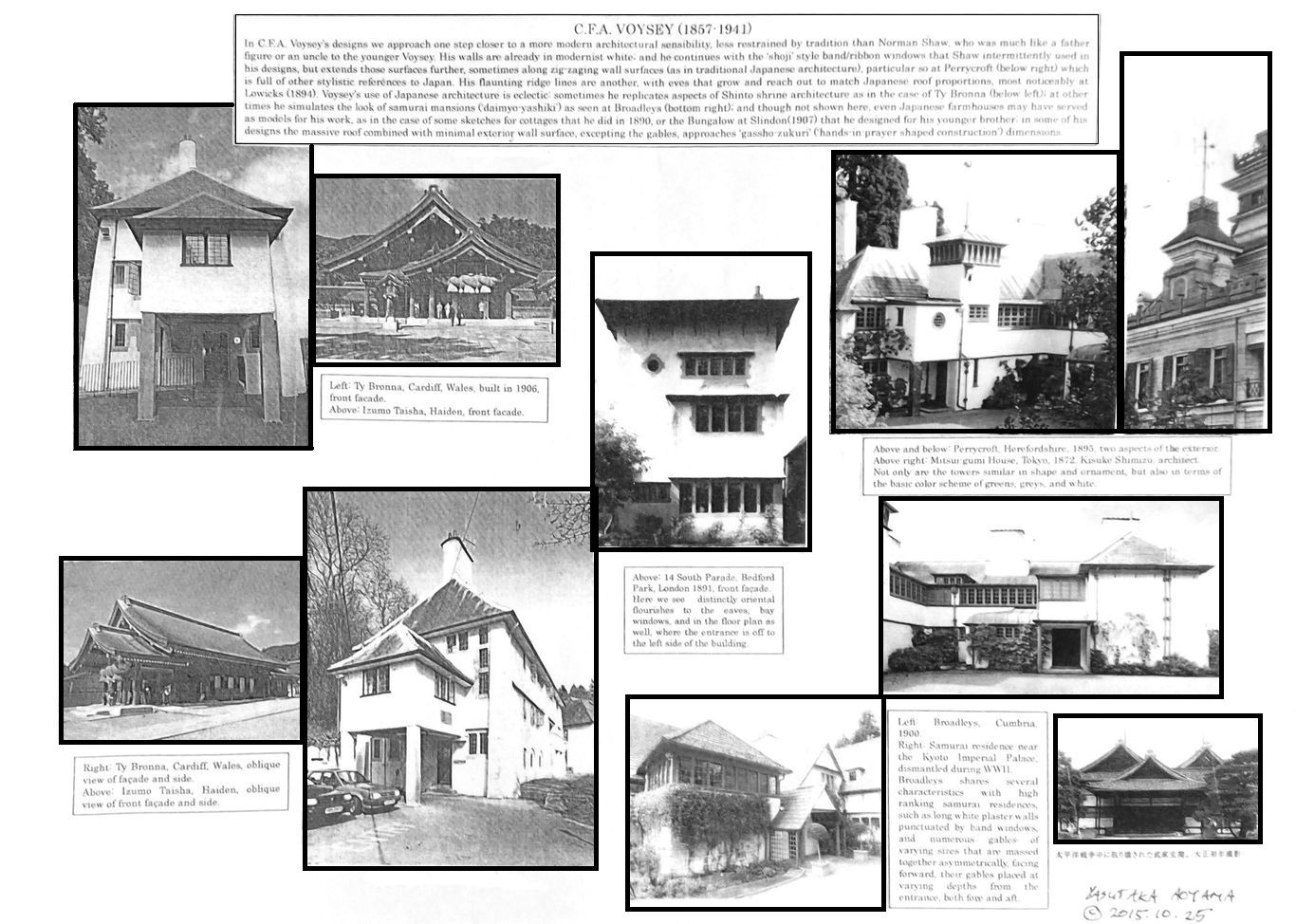

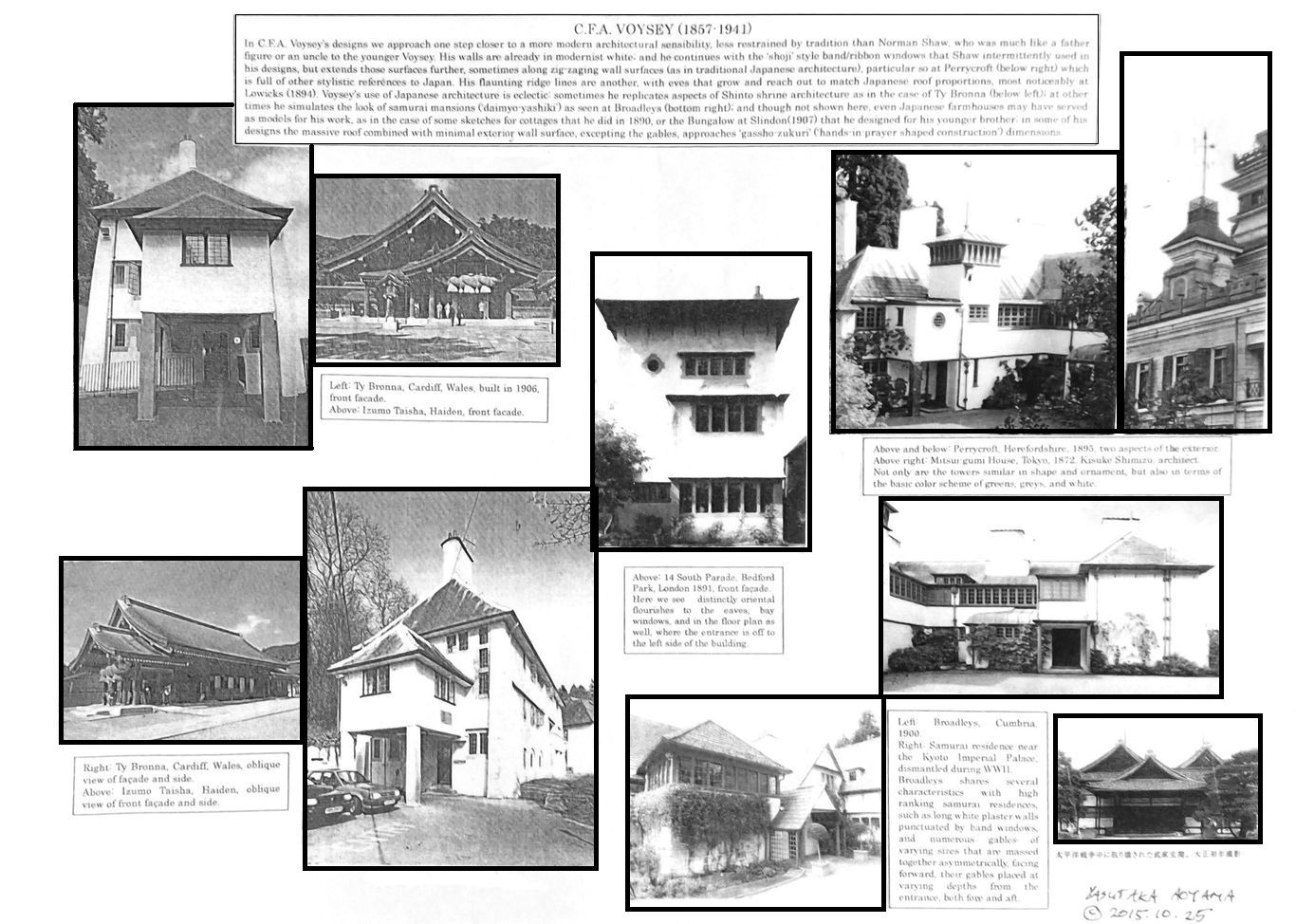

C. F. A. Voysey (1857-1941)

Part I: Exteriors

Perhaps Best Described as a 'Tibeto-Japanese' Melange

Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 22

Yasutaka Aoyama

Voysey's creative sources have not been sufficiently investigated. While his interiors can be evaluated within the context of the general trend of japonisme, his exteriors, while exhibiting elements of Japanese architecture, also exhibit commonalities with Tibetan, or more widely, Himalayan architectural forms, available, for instance, in the 1783 paintings of Bhutan dzongs by Samuel Davis.

The Tibeto-Bhutan parallels aside, circumstances and relationships of Voysey point to a link with Japanese art. For instance, Voysey, on the recommendation of his friend Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo (known for his involvement with Japanese interiors most notably that of the Mortimer Mempes House discussed later in this section), tried his hand at designing wallpaper, carpets, and textile designs, often using motifs which were very likely taken from katagami designs, an example of which is shown in Katagami Style (2012, supervised by Mabuchi Akiko, Director of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo) of a poppy flower motif for a decorative fabric (c. 1894, exhibit #2033). The 1890's was a time when publications on Japanese design became readily available, and the astonishing diversity and dramatic visual impact of katagami attracted designers in all fields, including architects.

The following added 2024.9.14

Robert Schmutzler, a leading historian of Art Nouveau in the English-speaking world, in his classic Art Nouveau (1962,1977), after commenting on how Voysey was influenced by Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo, writes:

“However, for Voysey as an architect, Japanese influences were perhaps even more important, though they are scarcely recognizable as such in his work. One of his most interesting works, the tower-like house in Bedford Park [shown below, center] that he finished in 1891, is an exception. The light roof with its low gradient, the concave curved roofing of the oriels, the thin metal supports that seem to raise the roof over the body of the building, the unusually small windows, and the one stressed bull’s-eye window are not outright Japanese forms; but the graphic, abstractly ornamental, and asymmetrical character of the surfaces, the contrast in black and white between the apertures and the white-washed walls, not to mention the frieze-like disposition of various groups of windows under the thin horizontal ledges, all clearly reveal the relationship to Japanese architecture, easily recalling Japanese teahouses and small temples, as for example Voysey’s similar but lower and longer country houses, which are a particular national achievement of English art.” ---Schmutzler, Art Nouveau, 1977 abridged edition, pp. 128-9.

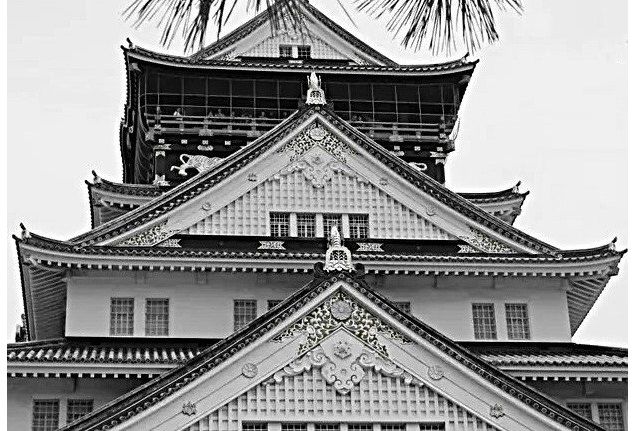

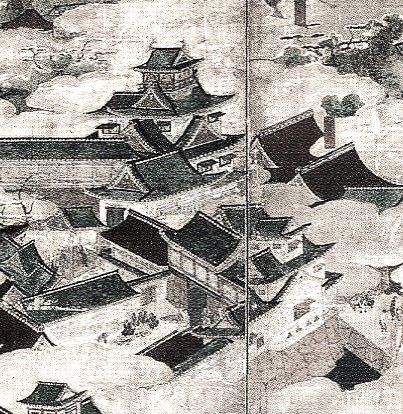

Yet we should add that those elements which Schmutzler categorizes as not obviously Japanese forms, as a low gradient roof, concave curved roofing, thin supports that raise the roof over the body of the building; or the bull’s-eye window---are in fact common features of traditional Japanese architecture, though not necessarily found together in one building. Even the small windows could be considered so, if we think of Japanese castle architecture. Indeed, the whole structure resembles a Japanese castle in various respects, including the frieze-like disposition of various groups of windows under the horizontal ledges, the white washed walls and their thick appearing aspect, and the contrast of black and white, though this is shared with Tibetan and Bhutanese architecture as well.

As to which inspired Voysey, Japan or Tibet/Bhutan in this case, either or both are possible; but as so much of his other architectural work reflects Japanese elements, both in his exteriors and interiors, as well as in his other designs, with hints such as “Tokyo” (wallpaper, 1893), the former seems more likely. Furthermore, models of Japanese castles were exhibited in Britain and on the Continent in world expositions and privately collected, and paintings and prints of castles abounded in England by the time of Voysey’s designing the Bedford Park house. On the other hand, Tibetan/Bhutanese models were scarcer though existing in sketches and paintings by a few, but we would not like to close the door on the possibility. It is an intriguing parallel, and at the very least it deserves mention as enriching our global perspective on modern architecture, even if there is no causative connection.

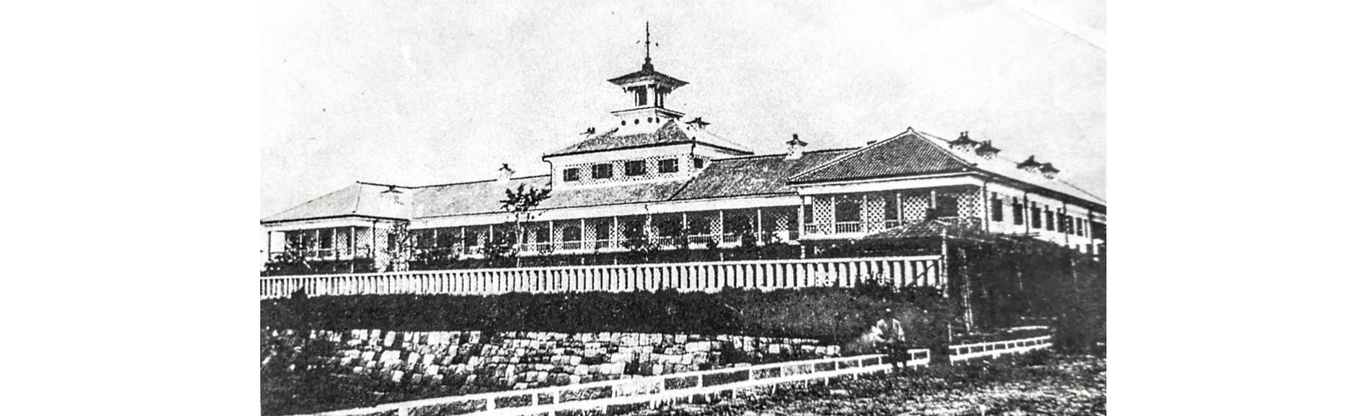

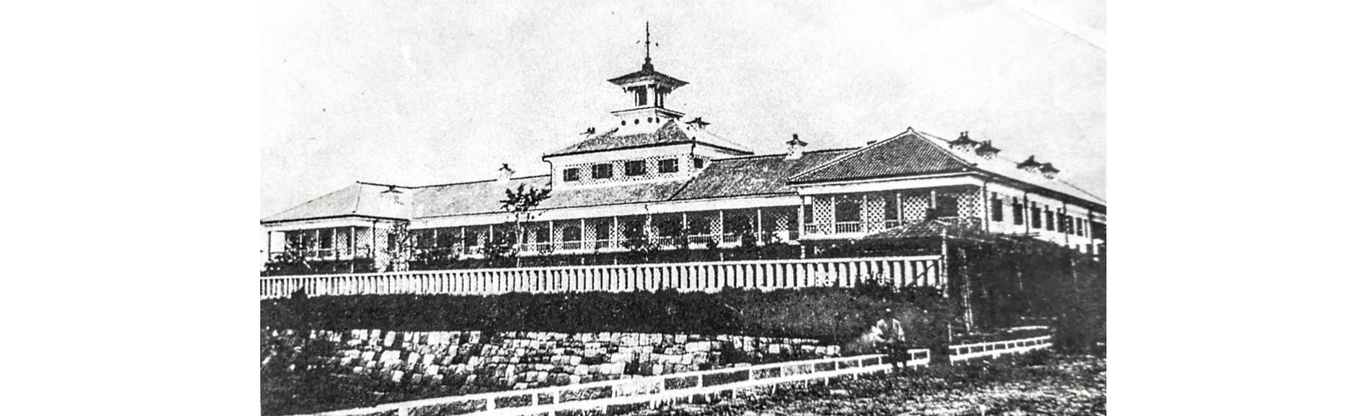

Below: An example of early Meiji era architecture, the Tsukiji Hotel, Tokyo, 1868. This was a hotel built for Western visitors. There are aspects of its design reminiscent of Voysey. Novel architectural forms were being produced in abundance in Japan from the late 1860's onward to the early 20th century, that precede the appearance of similar forms in the West. It might be said that much of the reputation for originality of certain architects in Europe or America in those days depends on an ignorance of the building activity going on in Japan at the time.

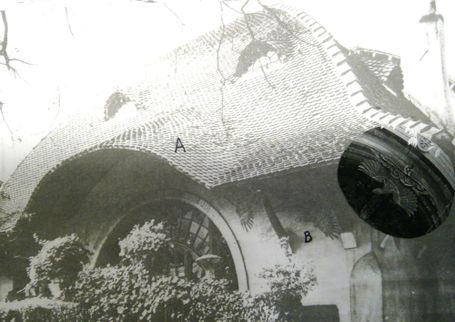

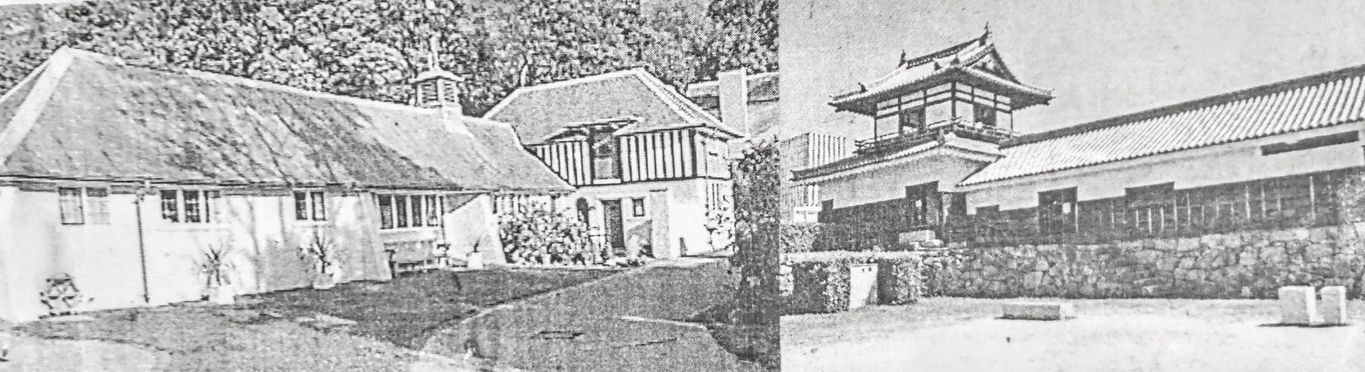

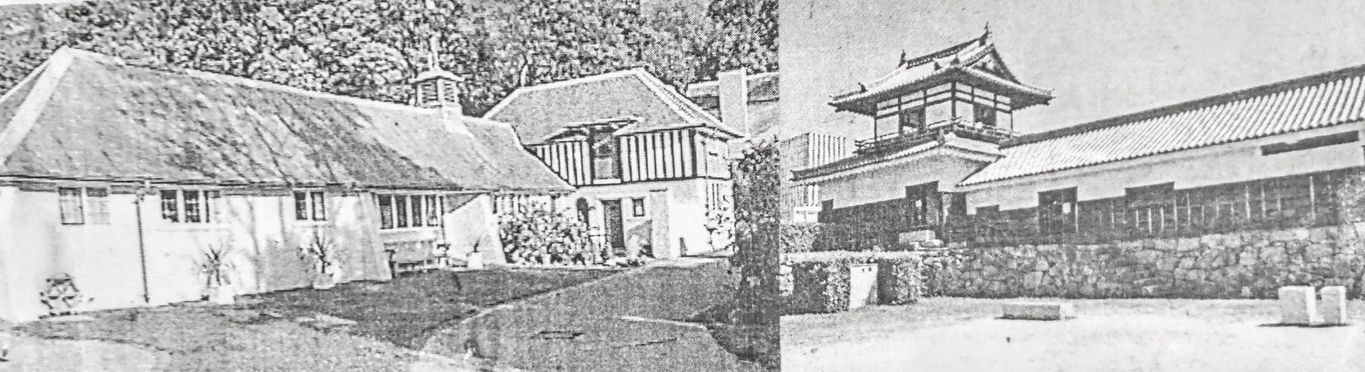

Below: Photos pasted side by side from the author's scrapbook, on the left is a Voysey designed house, on the right a Japanese castle 'yagura' (a corner tower and storehouse/sentinel quarters combination). Despite obvious differences, there is an affinity of general conceptualizations between Japan's and Voyseys' architecture.

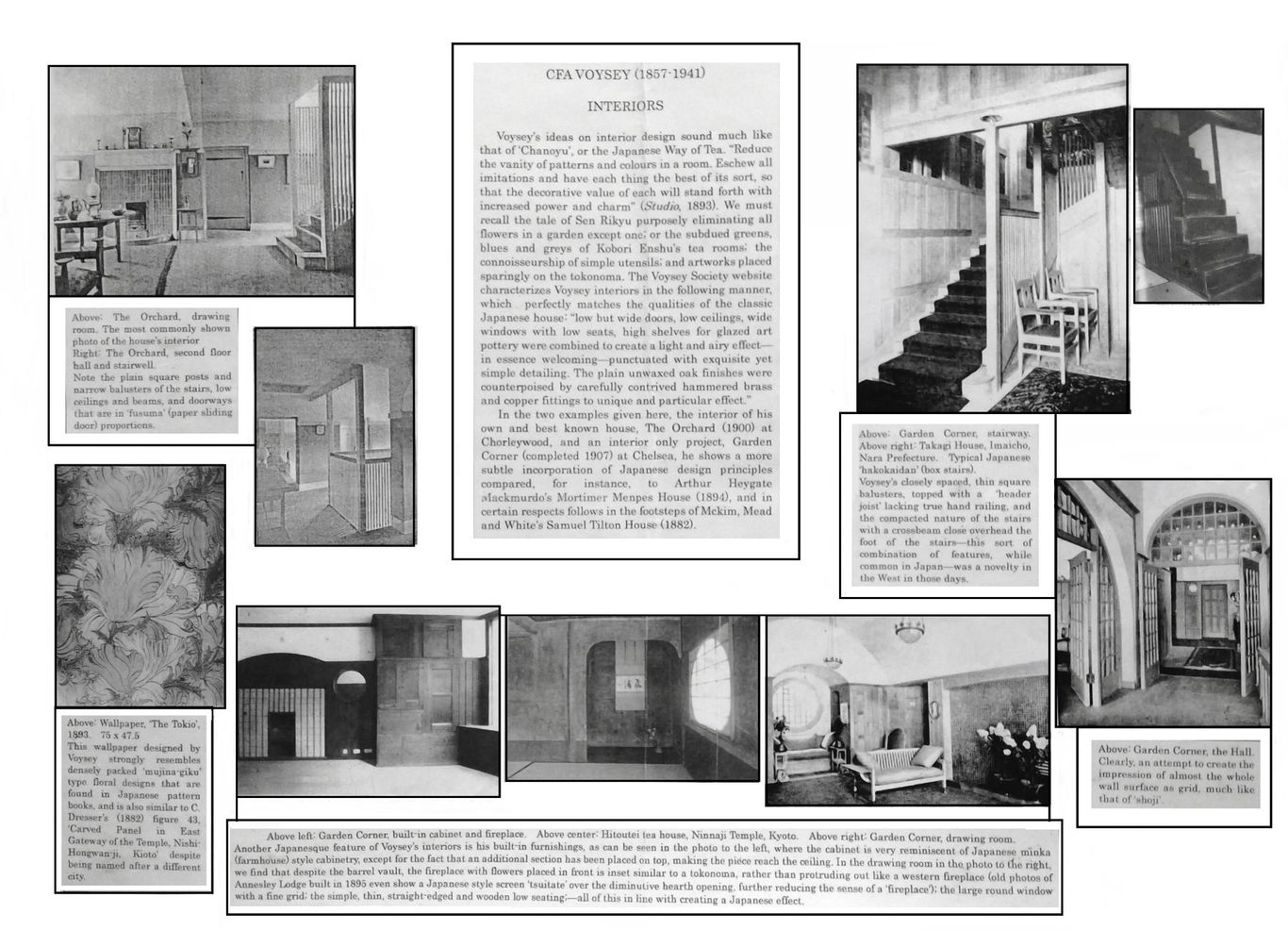

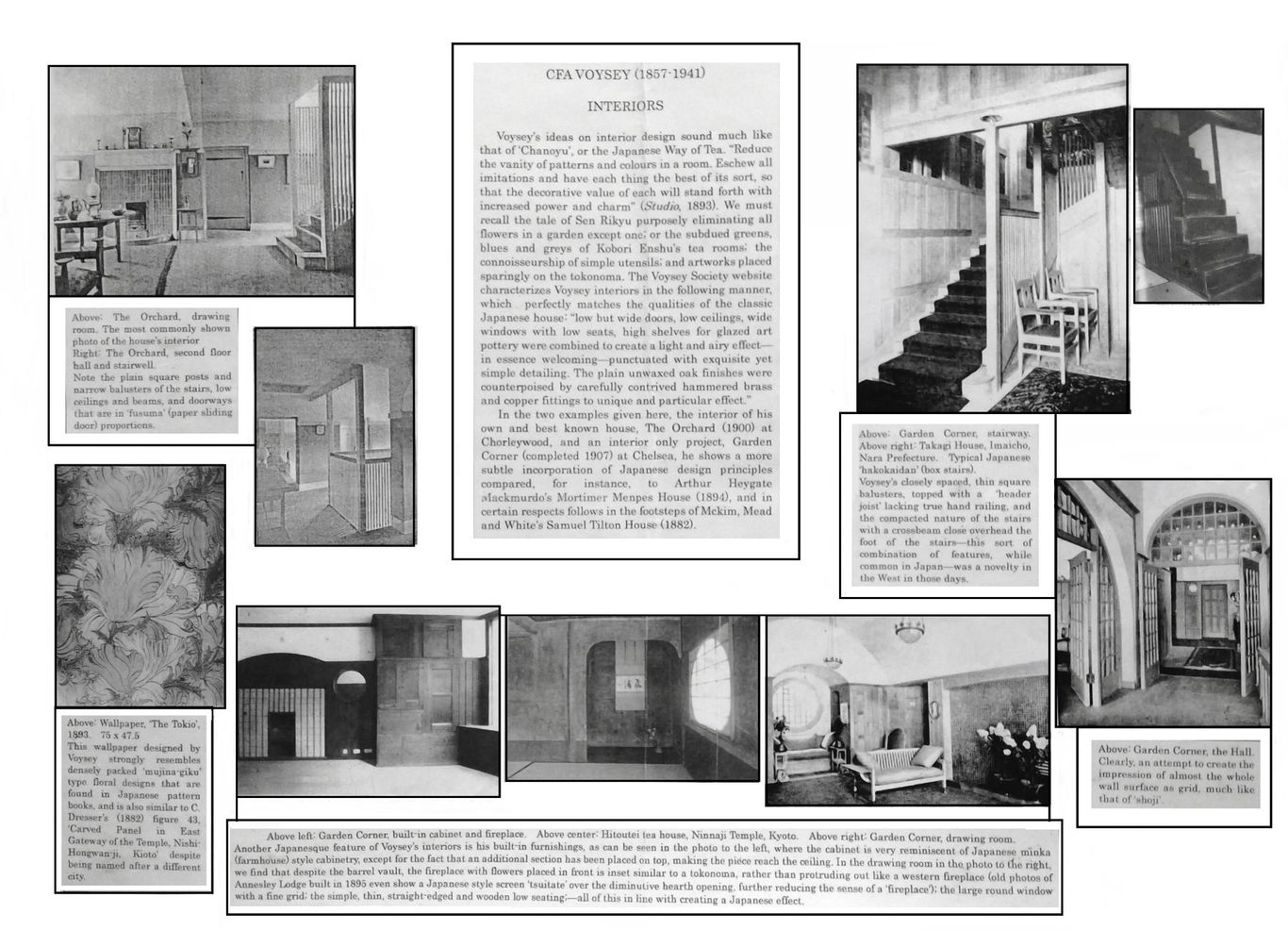

C. F. A. Voysey (1857-1941)

Part II: Interiors

Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 23

________________________

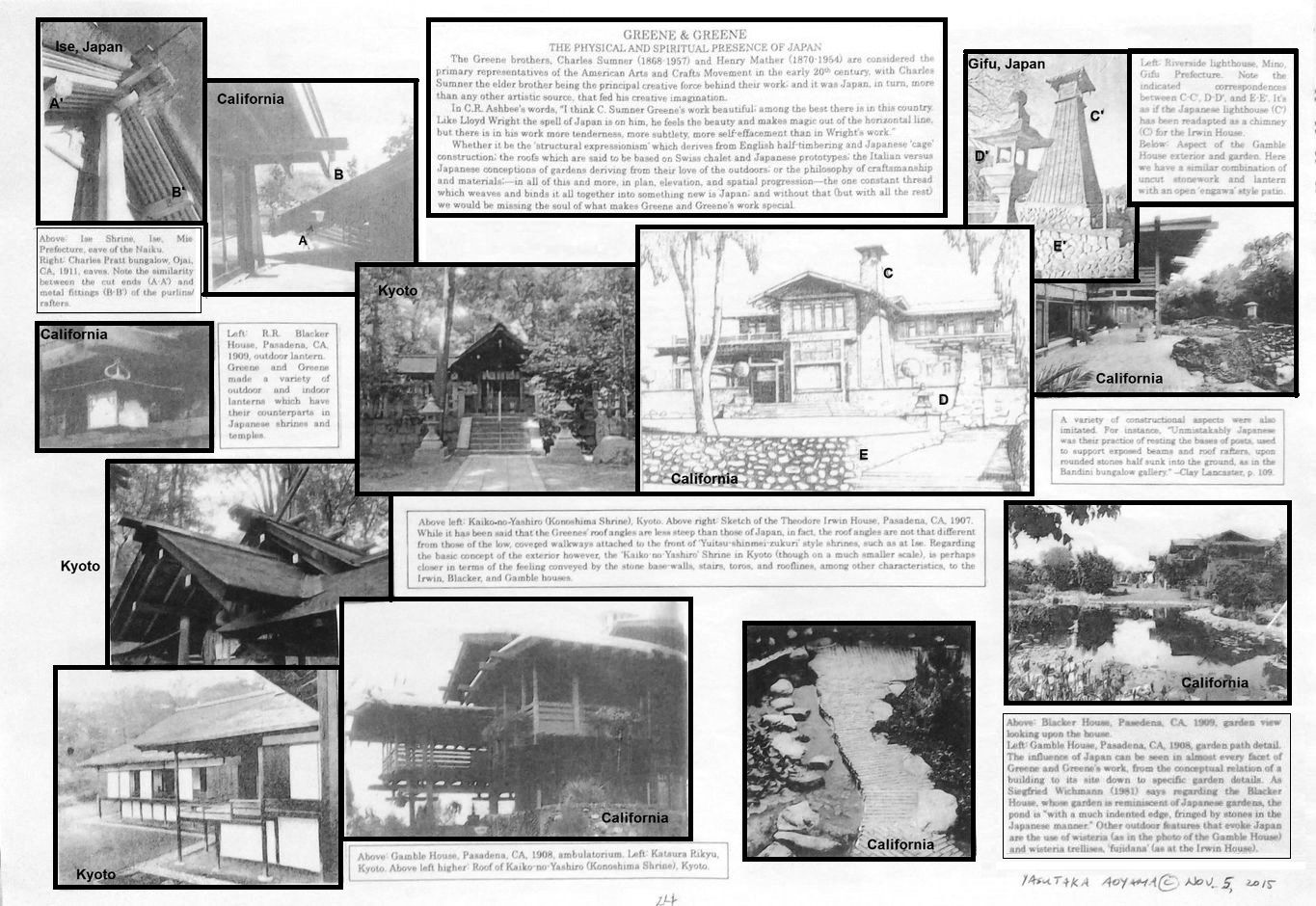

Greene and Greene

Charles Sumner (1868–1957) & Henry Mather (1870–1954)

Part I: The Physical and Spiritual Presence of Japan

Lecture handout 2015.11.5, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 24

Yasutaka Aoyama

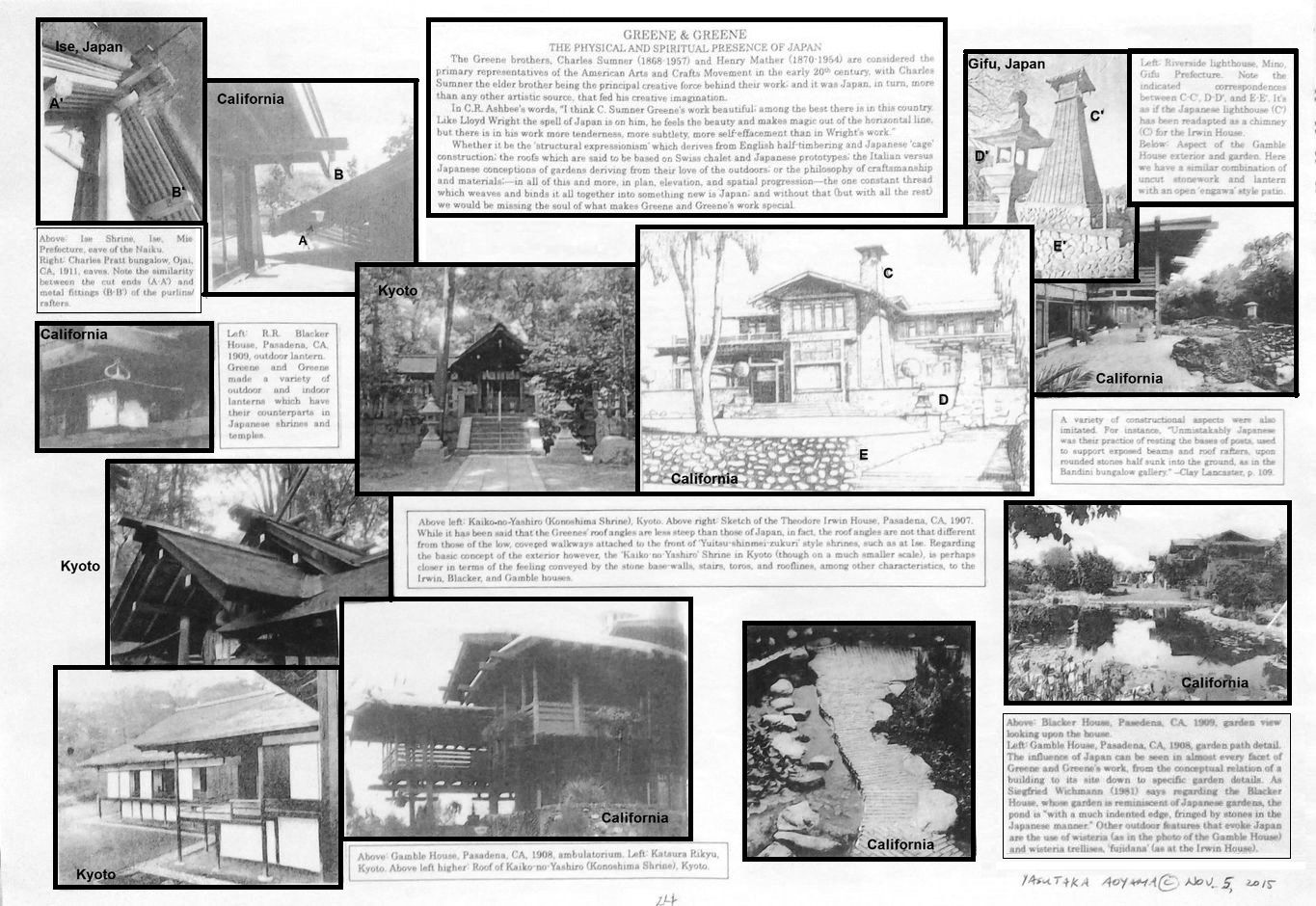

The Greene brothers, Charles Sumner and Henry Mather, are considered the primary representatives of the American Arts and Crafts Movement of the early 20th century, with Charles Sumner, the elder brother, being the principal creative force behind their work; and it was Japan in turn, more than any other artistic source, that fed his creative imagination.

In the words of Charles Robert Ashbee, of English Arts and Crafts renown, "I think C. Sumner Greene's work beautiful; among the best there is in this country (meaning the USA). Like Lloyd Wright the spell of Japan is on him, he feels the beauty and makes magic out of the horizontal line, but there is in his work more tenderness, more subtlety, more self-effacement than in Wright's work."

Vincent Scully, the pre-eminent historian of 19th century American architecture wrote: "Their use of materials---rough wood, cedar shakes, and cobblestones---also grows out of the use of natural materials of the shingle style [a Japanese influenced style according to Scully] but in a sense exaggerates it, insisting obsessively upon the total articulation of each element. Also significant in their work is a strong oriental influence, the apotheosis of that insistent relationship with Japanese framing and spatial techniques which had been important since the 70's [1870's]." (The Shingle Style and The Stick Style, Revised Edition, 1971, p.157)

While Henry-Russell Hitchcock, usually sparing in his comments regarding the role of Japan in his Architecture: Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (The Pelican History of Art), considers the Greene's houses "most interesting for their successful assimilation of oriental influences", writing: "Shingled walls, low-pitched and wide-spreading gables, and extensive porte-cocheres and verandas of stick-work surpassing in virtuosity those of the Stick Style, were combined by the Greenes in rather loosely organized compositions. Less formal and regular than Wright's Prairie Houses, theirs are executed throughout with a craftsmanship in wood rivalling that of the Japanese, whom they, like Wright, so much admired." (1977, p. 452)

Other architectural historians have characterized it in various ways; but whether it be the 'structural expressionism' of their designs which derives from English half-timbering and Japanese 'cage' construction; the roofs which are said to be based on Swiss chalet and Japanese prototypes; the Italian and Japanese conceptions of gardens deriving from their love of the outdoors; or the philosophy of craftsmanship and materials;---in all of this and more, in plan, elevation, and spatial progression---the one constant thread which weaves and binds it all together into something new---is Japan; and without that (but with all the rest) we would be not missing the soul of what makes Greene and Greene's work special?

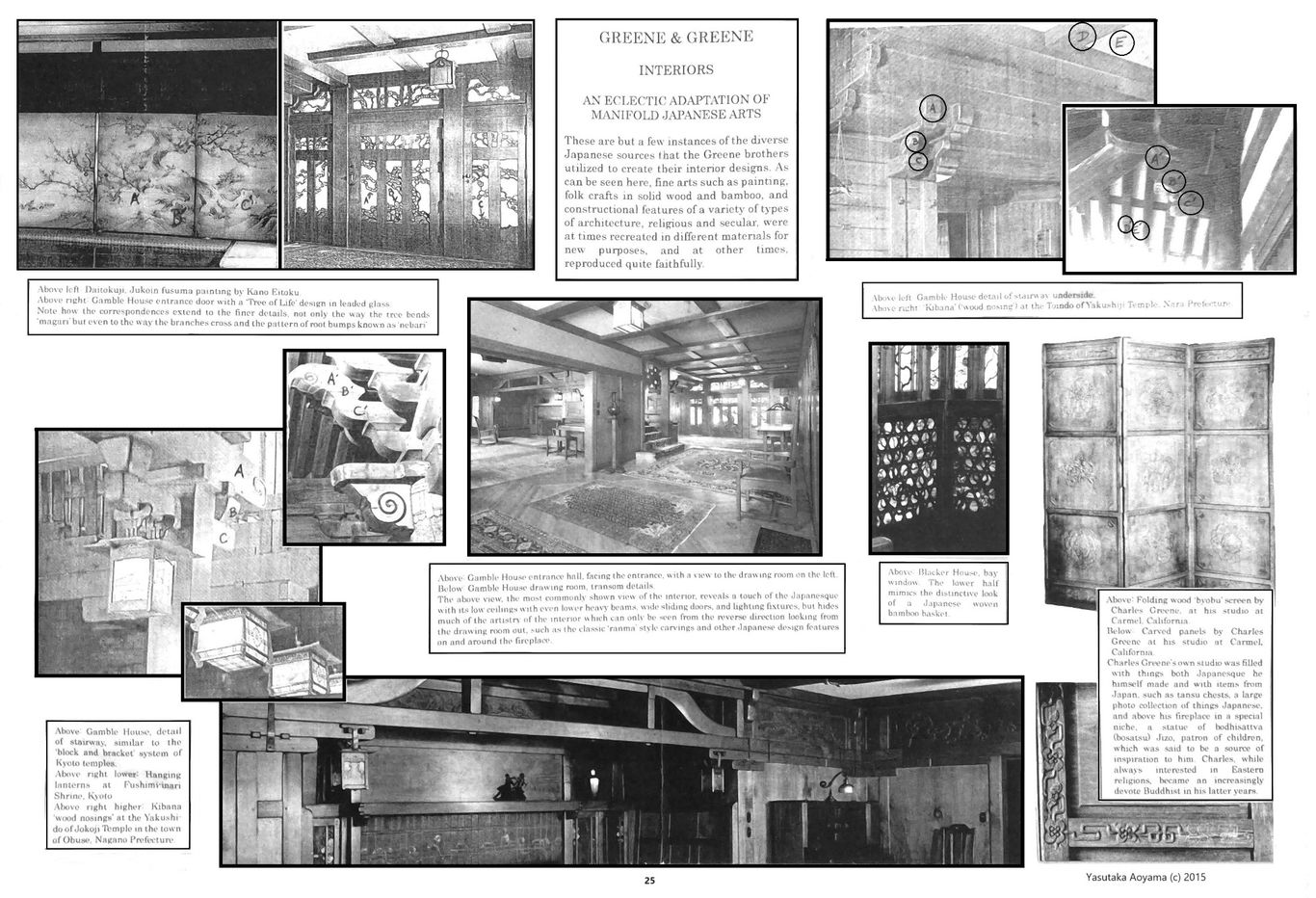

Greene and Greene

Part II: Interiors

An Eclectic Adaptation of Manifold Japanese Arts

Lecture handout 2015.11.5, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 25

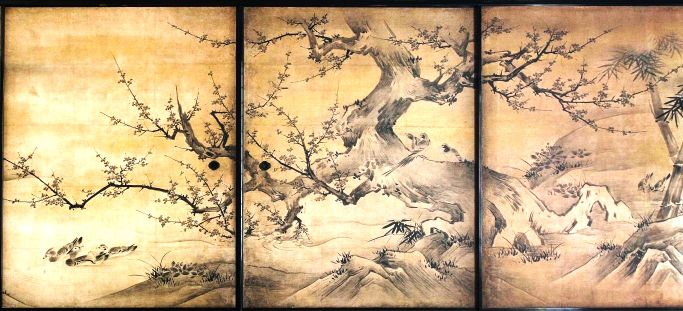

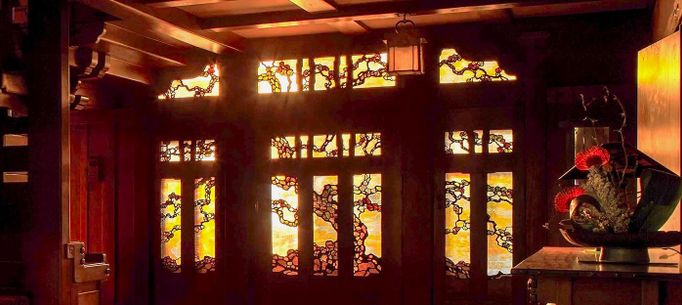

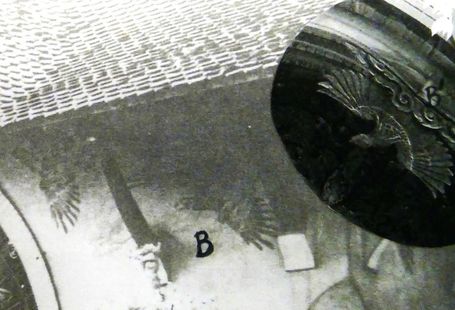

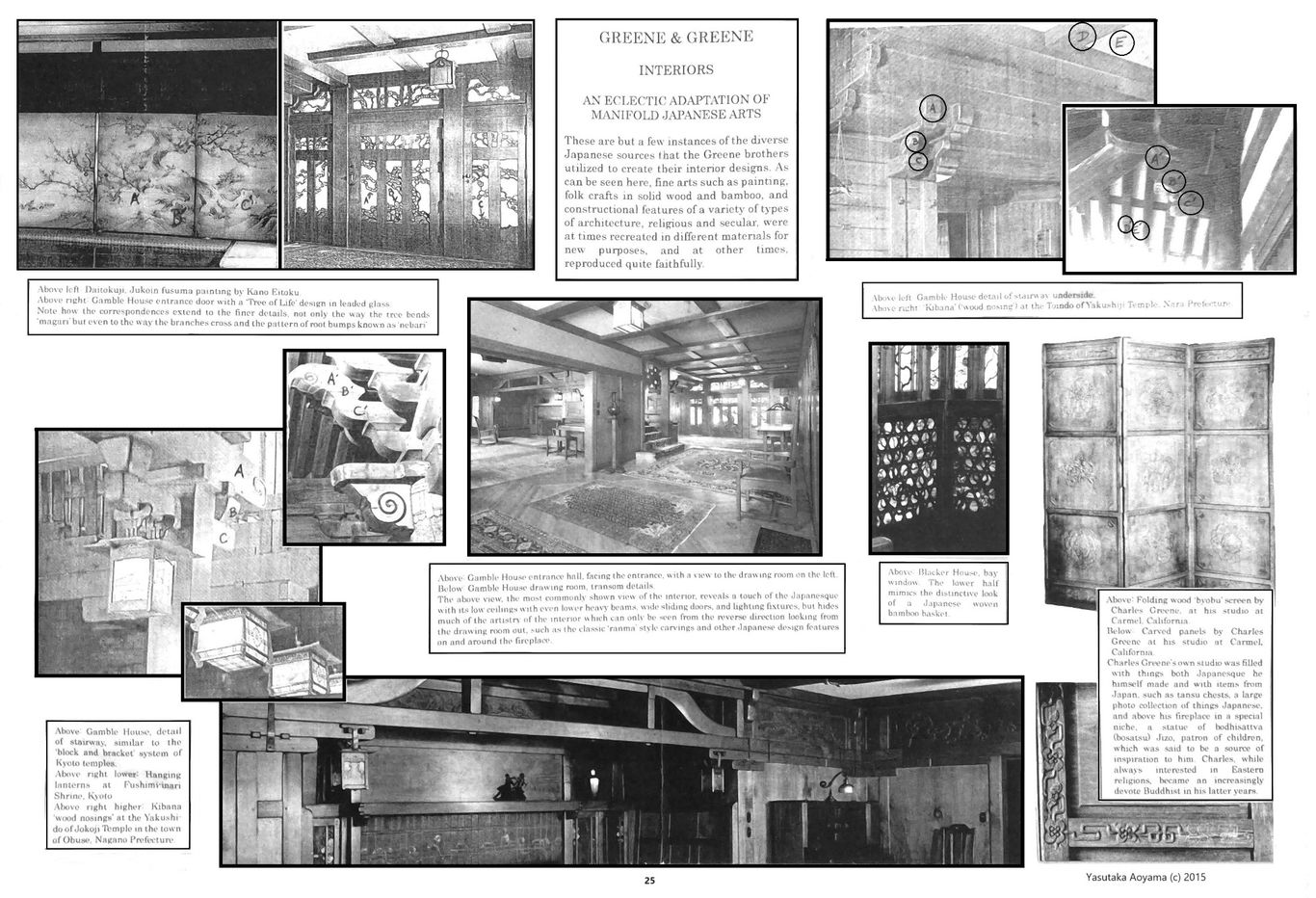

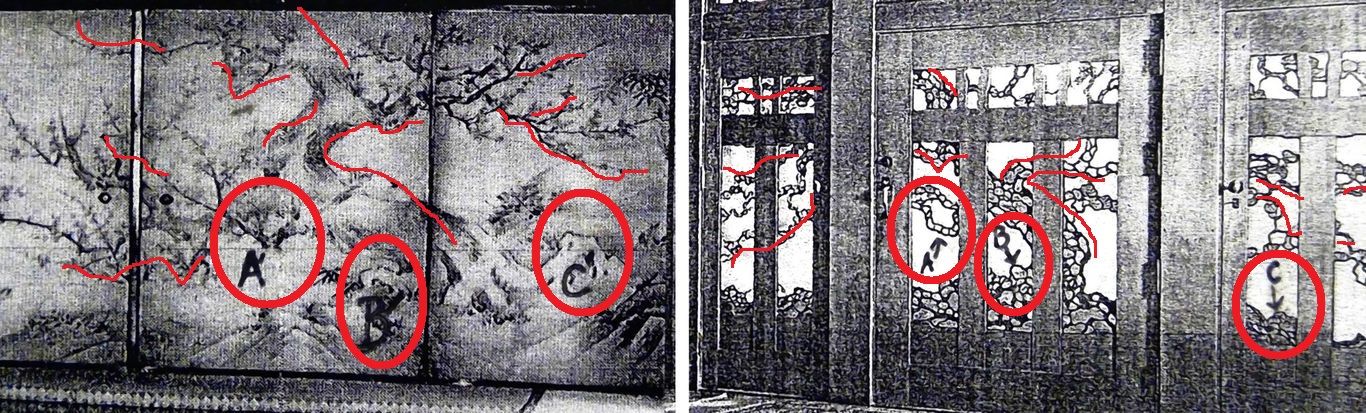

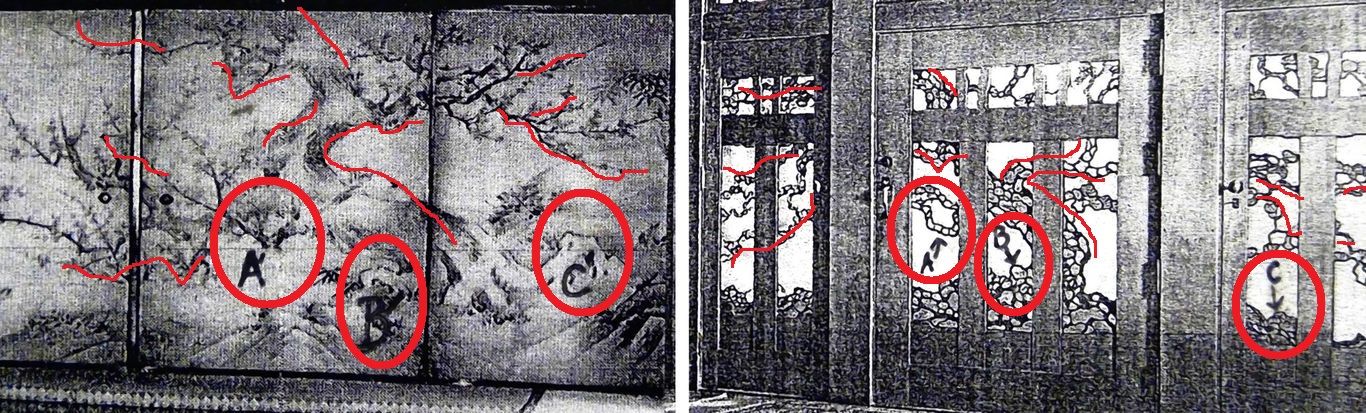

Below: Close up of the Daitokuji Temple Jukoin fusuma (sliding door panel) by Kano Eitoku (left) and the Gamble House entrance door with the 'Tree of Life' design in leaded glass (right). Note how the correspondences extend to the finer details (e.g. A=A', B=B', C=C') not only in the pronounced way in which the tree bends and extends horizontally known as 'magari' but even to the way the branches cross and the pattern of root bumps know as 'nebari'. In Japan the aesthetic appreciation of the details of garden tree shape, like bonsai, especially their sideways extension was a matter of high connoisseurship.

Bottom two photos from Wikipedia.

________________________

McKim, Mead and White

Charles Follen McKim (1847–1909), William Rutherford Mead (1846–1928) and Stanford White (1853–1906)

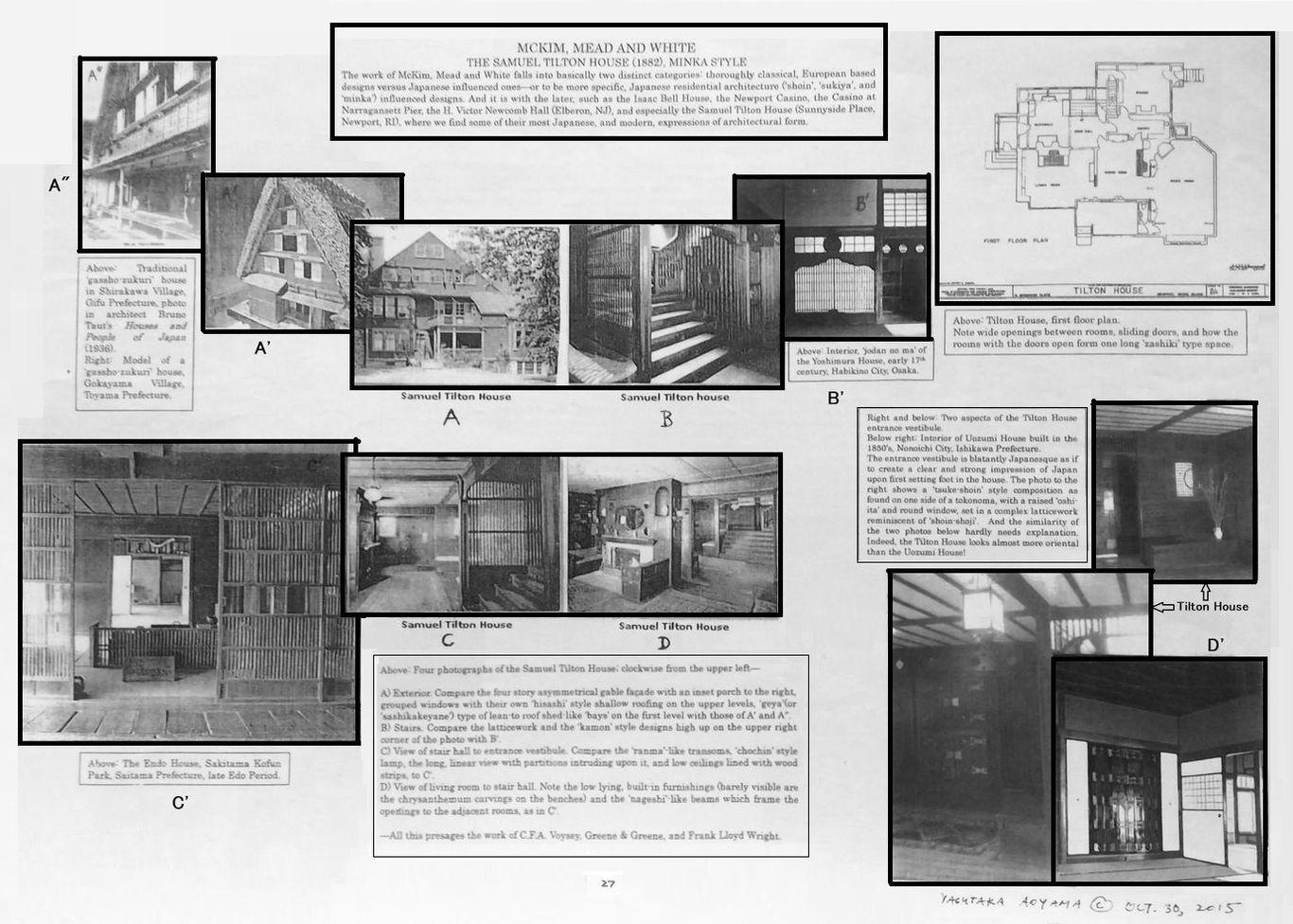

The Samuel Tilton House, American 'Minka Style'

Lecture handout 2015.10.30, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 27

Yasutaka Aoyama

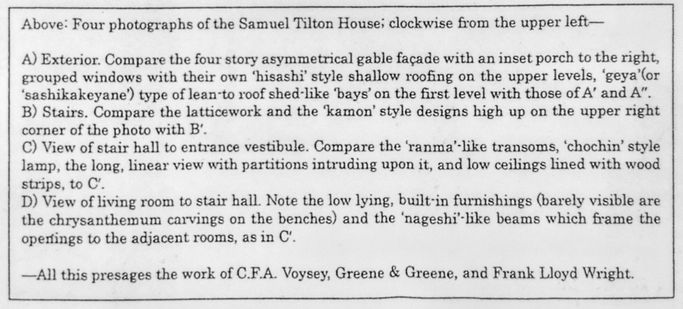

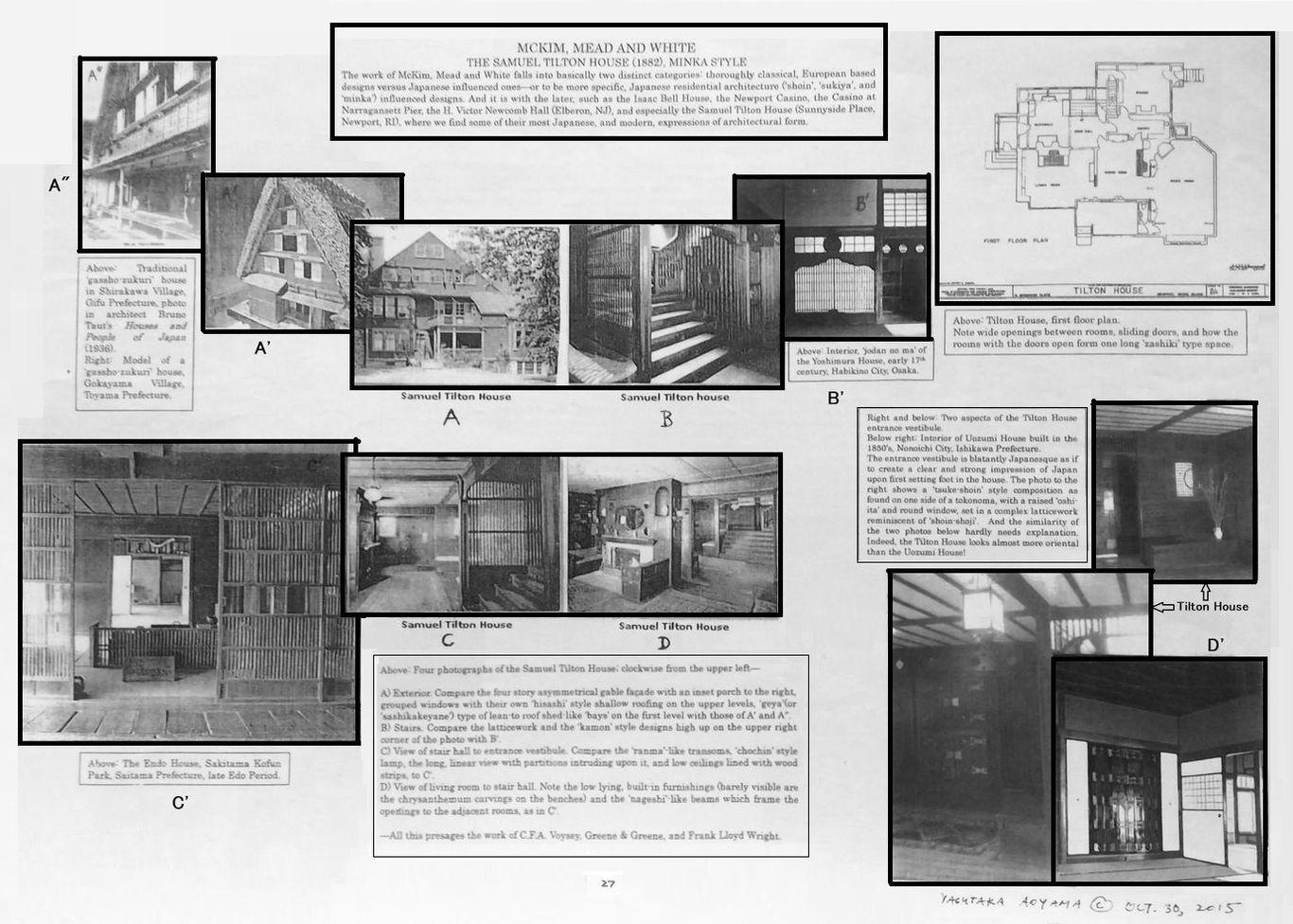

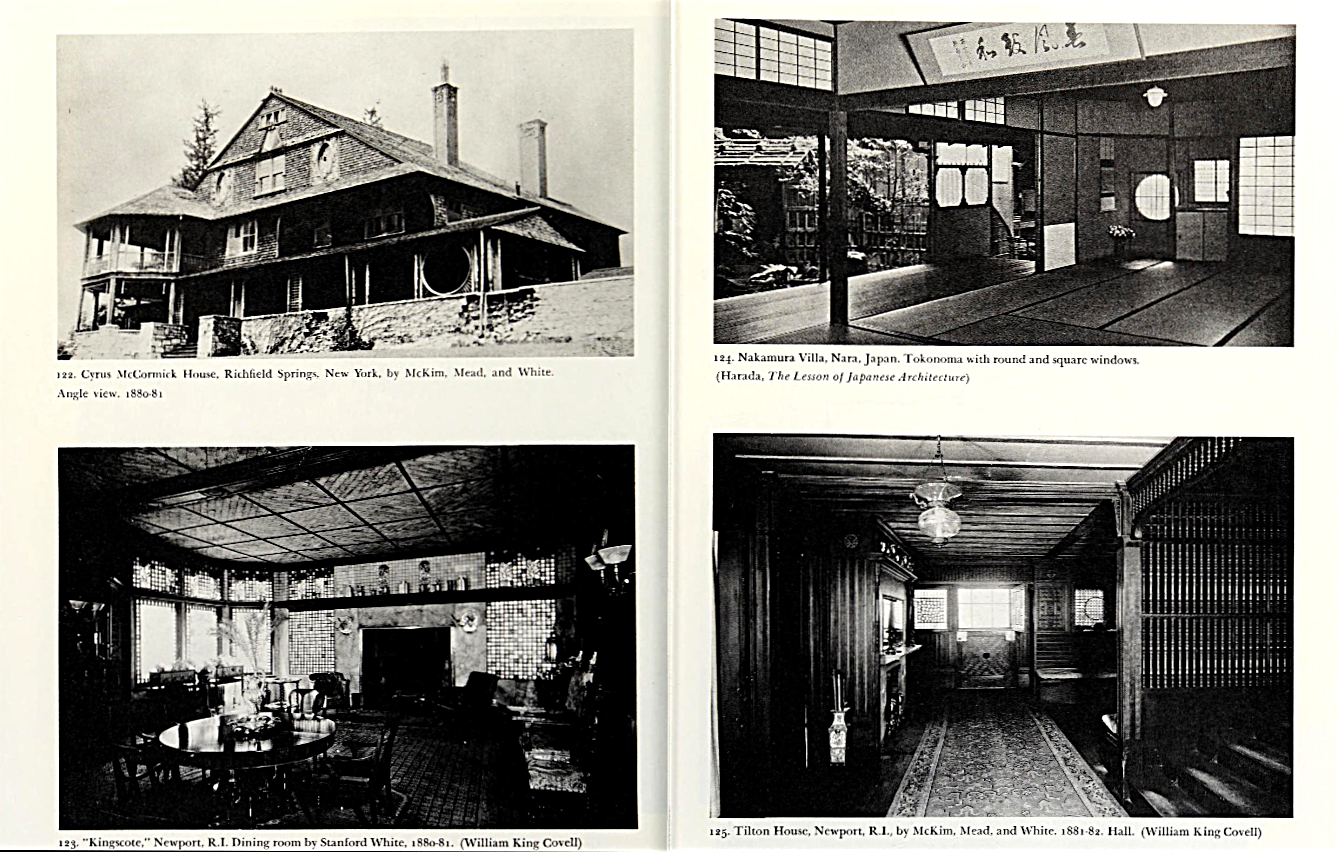

The work of McKim, Mead and White falls into basically two distinct categories: thoroughly classical, European based designs vs. Japanese influenced ones---or to be more specific, Japanese residential architecture ('shoin', 'sukiya' and 'minka') influenced designs. And it is with the later, such as the Isaac Bell House, the Newport Casino, the Casino at Narragansett Pier, the H. Victor Newcomb Hall (Elberon, NJ), and especially the Samuel Tilton House (Sunnyside Place, Newport, RI), where we find some of their most modern expressions of architectural form.

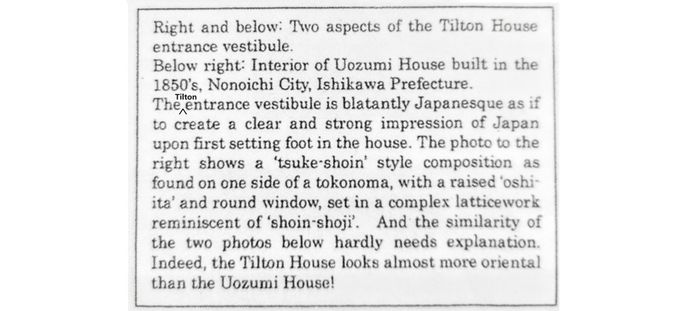

The text for two of the caption boxes (center bottom and right side middle) have been reproduced below for better legibility.

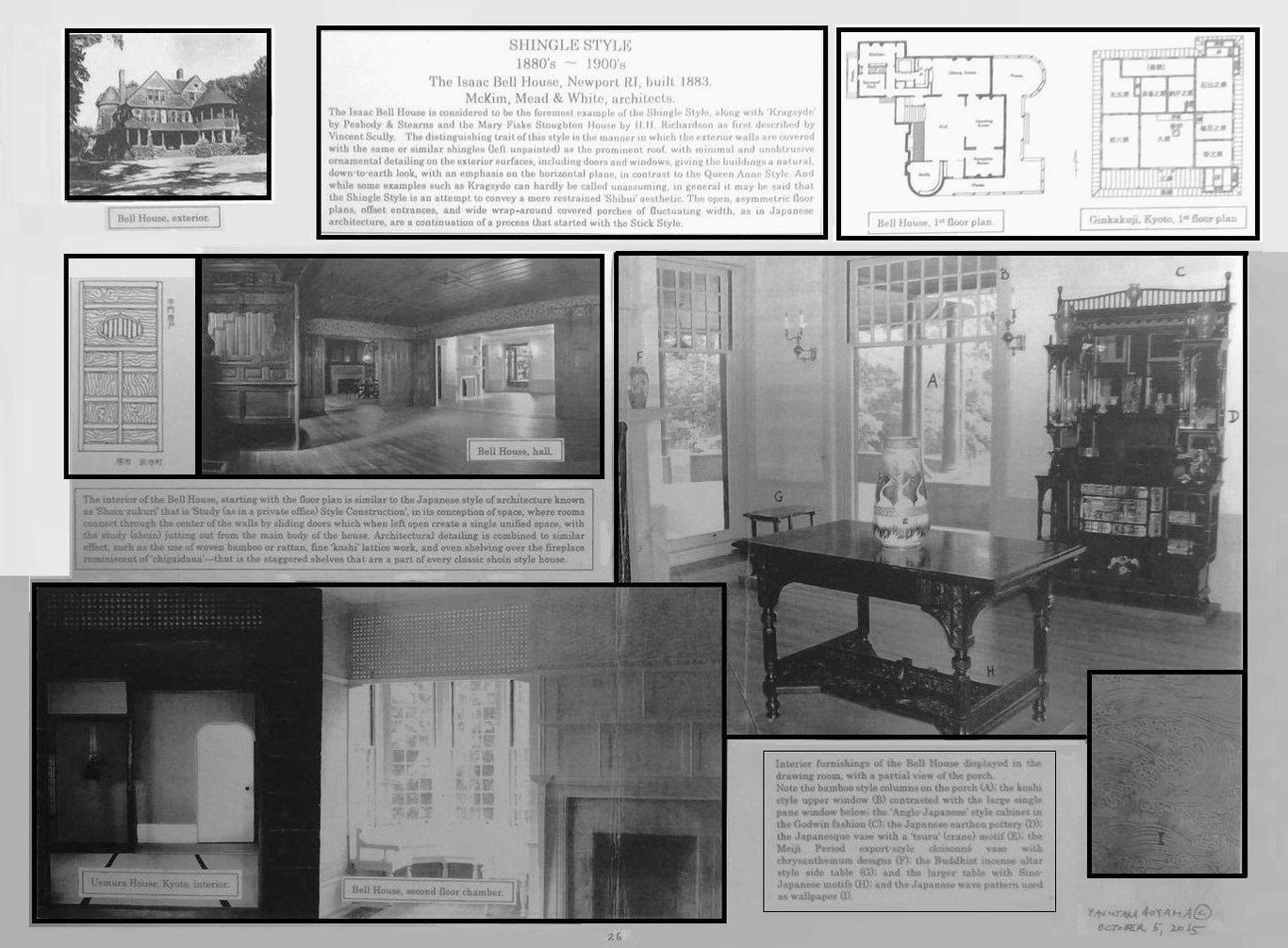

McKim, Mead and White

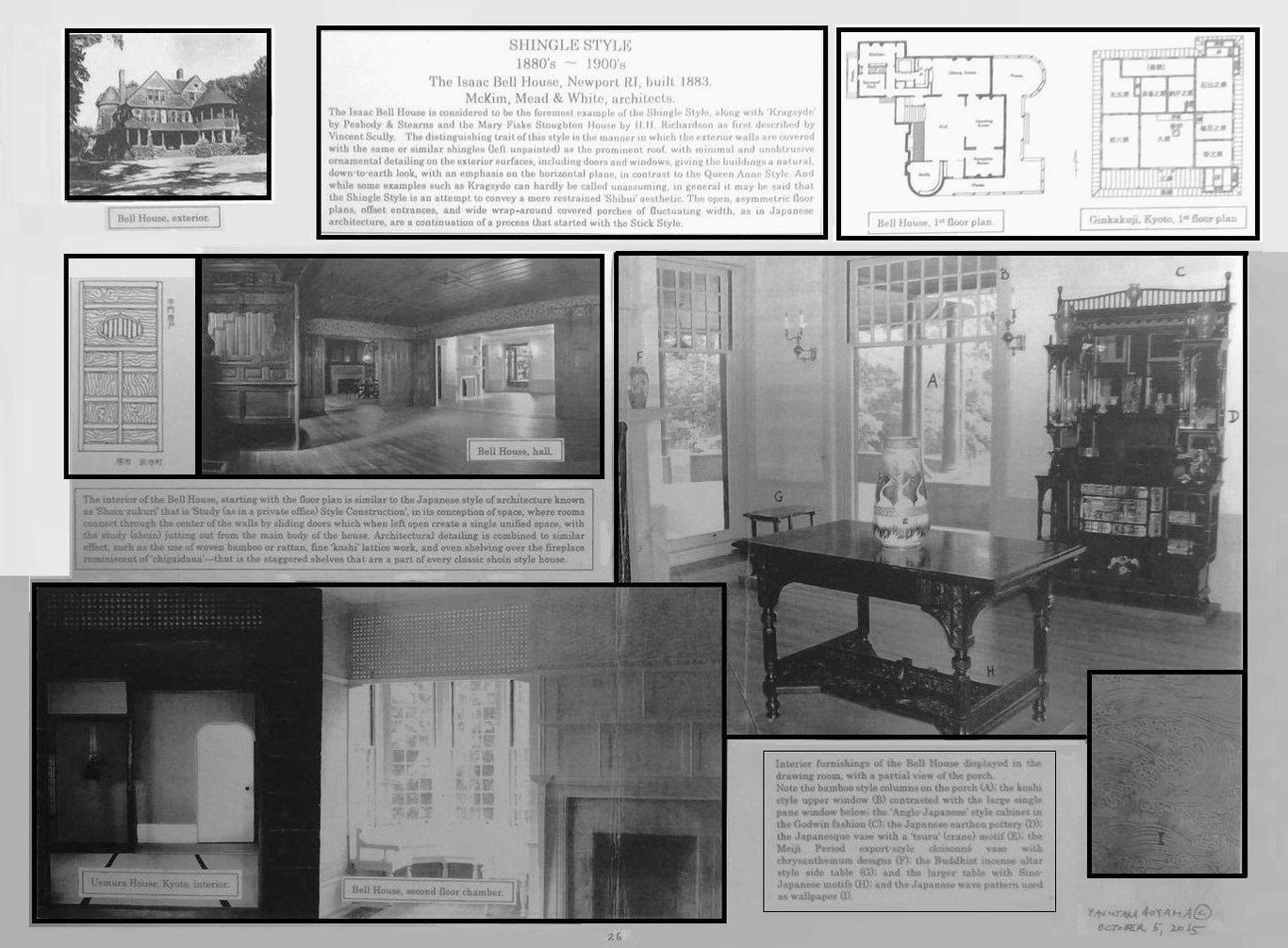

The Isaac Bell House and Japan in the Shingle Style (1880's -1900's)

Lecture handout 2015.10.5, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 26

Yasutaka Aoyama

The following text added 2024.6.18:

The above are but a sampling of the Japanese influences seen in McKim, Mead and White, and various other designs could be raised as examples:

Regarding the "remarkable" Casino at Newport, Rhode Island (1879-81), Vincent Scully writes: "The differentiation in scale here between the framing members and the grilled panels between them recalls Japanese wooden architecture---with the post, the kamoi, and the ramma---and reveals McKim, Mead and White's important amalgamation of influences from that source with indigenous American framing habits. ... It combines a sense of order by no means academic with a variety of experiments in picturesque massing and spatial articulation. More over, it combines Japanese and American stick-style sensitivities with that sweep of design which is typical of the shingle style." (The Shingle Style and Stick Style, revised edition, 1971, pp. 132-133) Even the "experiments in picturesque massing and spatial articulation", as well as the "sweep of design", however, have their precedents in Japanese architecture, which perhaps Scully is not fully aware of.

As for the Victor Newcomb House at Elberon, New Jersey (1880-81), "a building which exhibits qualities more peculiar to McKim, Mead, and White at their original best", we will quote Scully at some length, for it contains some very important observations:

"The hall is paneled in vertical wood siding, with battens, up to door height, where a strip molding passes around the wall. This molding is continuous above the dorrway openings. It is a decorative and nonstructural derivation from the Japanese kamoi, the bracing beam below which the screens slide in a Japanese interior. The space between molding and celing in the Newcomb House is filled by a latticework screen, derived from the Japanese ramma; this creates a continous flow of space, partially screened, between the hall and the other rooms, as well as a constant sense of scale. The Japanese use of the continuous beam or molding with open work above had been clearly described in the American Architect in 1876... As a concession to American living McKim, Mead and White eliminate here the movable screens, but they are obviously experimenting with the continuous frame and open work to give an impression of movability and spatial continuity. ... The elegantly rectangular floor pattern, probably derived from the Japanese mat and looking much like 20th century De Stijl work, also functions to enforce scale and spatial direction. ... The architecture itself is straightforward and decisively interwoven. The ceiling overhead, emphasized by the subtly varied exposed timbers---which are crisscrossed in patterns a little like a Japanese mat system---slides visually through from room to room; the continuity of human scale is kept by the molding. The spaces do not merely open widely into each other they actually penetrate each other; and the whole space thereby expands horizontally with absolute, not relative, continuity. While the toal space thus expands, each unit of space continues to keep its own individuality through the passage of molding and screen. Consequently, space is at once integrated and articulated. This spatial concept, representing a creative assimilation of Japanese influences, appears as a basic principle in the work of Wright; indeed it has been erroneously believed that Wright was the first to achieve it in America." (1971, pp. 134-136).

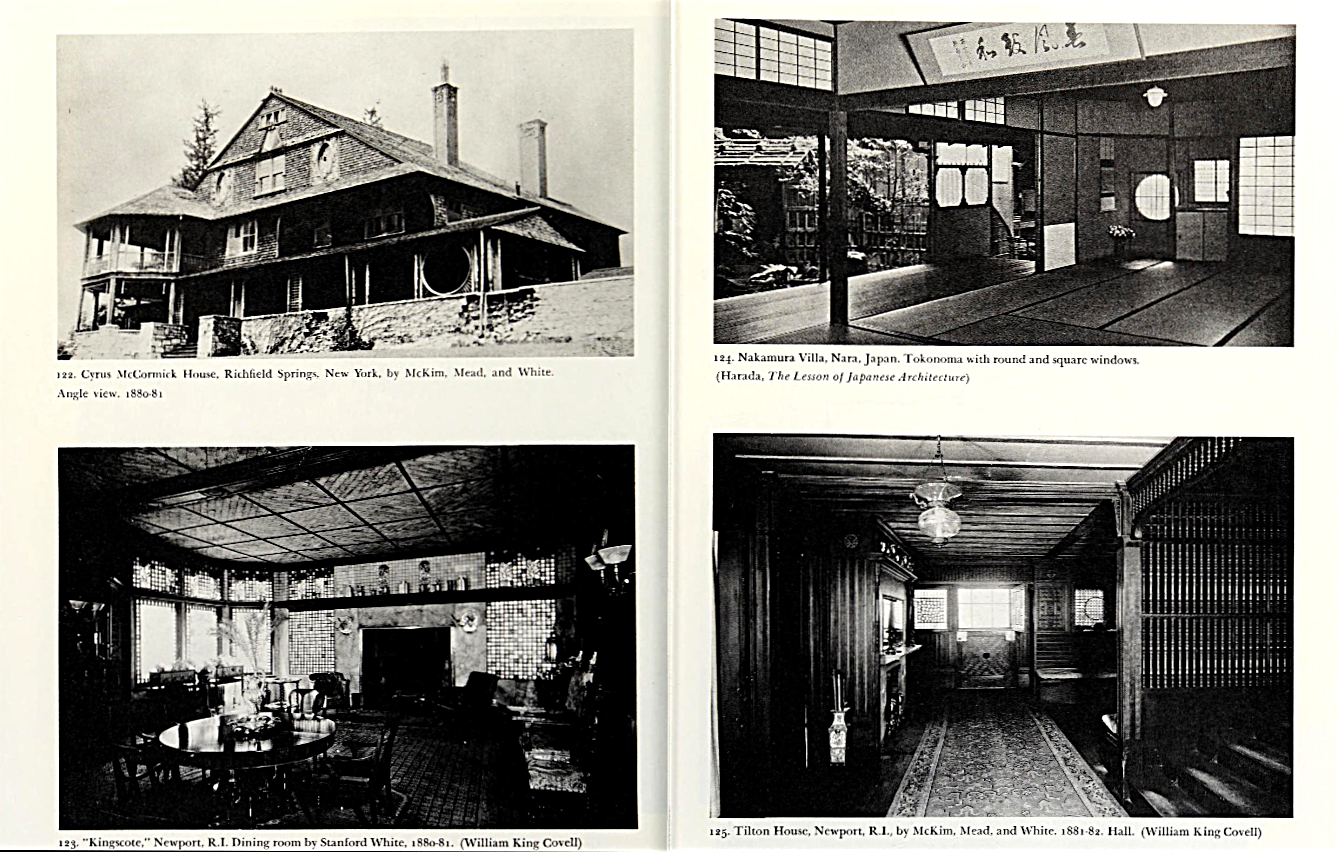

Concerning the Cyrus McCormick House at Richfield Springs, New York (1881-82), which Scully rates as "their best cottage building in the early 80's" thanks to its "lightness of scale and its creative combination of gable front, porch pavilions, and structural and textural vitality" with "its interwoven basketry of skeletal elements" he says: "Here again there is much of the Japanese and much of the later Wright." And adds that rooms in the house, "are equally distinguished and use delicately scaled details partly colonial, partly Japanese, and wholly proto-Art Nouveau." (p. 137)

From Vincent Scully, The Shingle Style and the Stick Style, Revised Edition (1971), where he includes a photo of the Nakamura Villa of Nara for comparison with various shingle style houses.

Further Examples of the Shingle Style

and

Diversity in Japanese Regional Farmhouse Architecture

The Japanese influence upon the Shingle Style has been discussed by Vincent Scully in his classic work of the same name; we should add here that within the Japanese influenced exterior elements, not uncommonly the original interiors had rooms also of a Japan-conscious style.

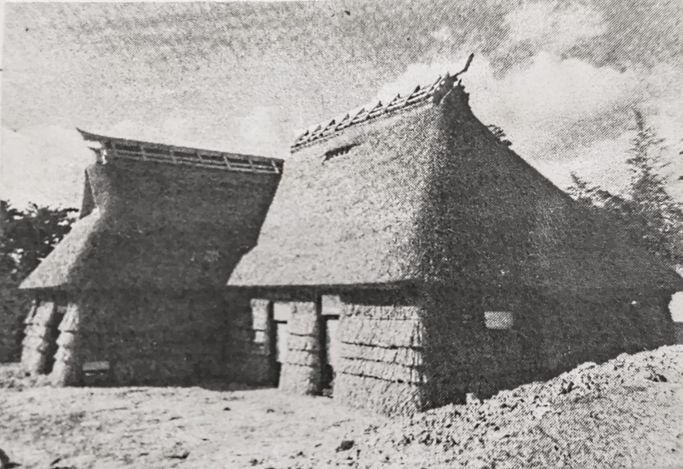

Note below how the shingles of the Stroughton House resemble the overlapping, down to earth effect of the straw-like fiber walls of the Japanese farmhouse, and how the rounded house corners and staggered walls of the latter are also recreated in the former by the roundish turret and house extensions which likewise are made to blend together without sharp corners.

________________________

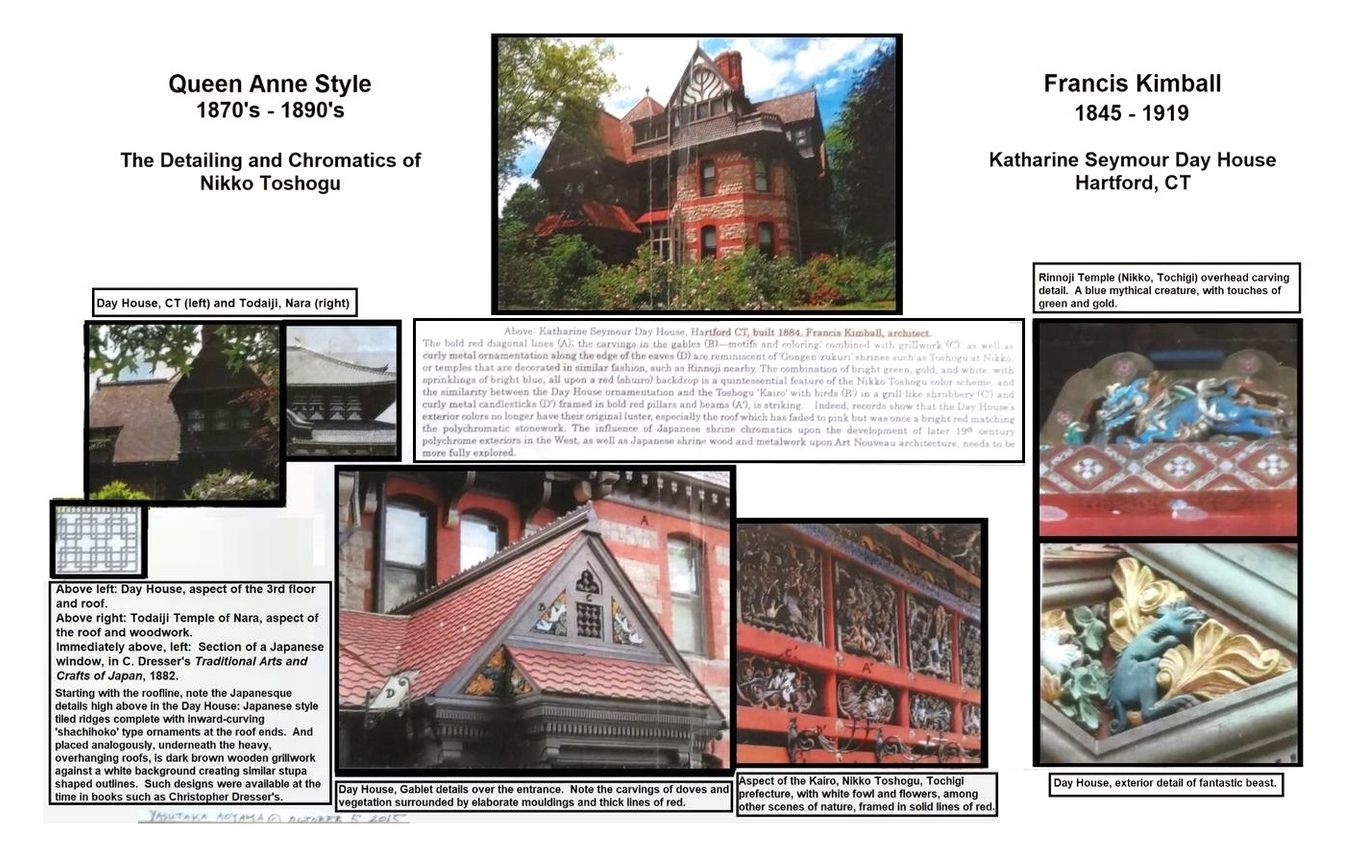

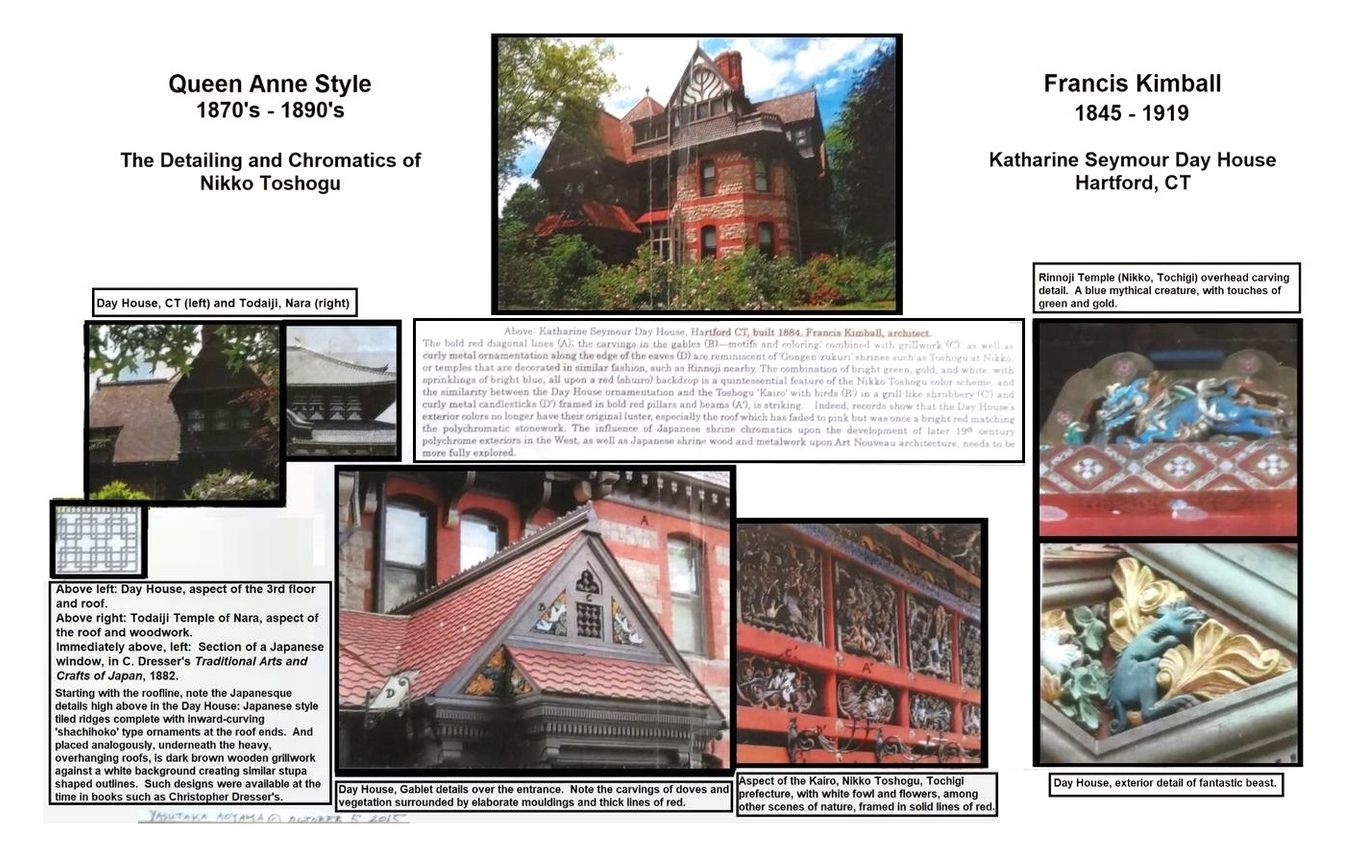

Queen Anne Style in America (1870's to 1890's)

The Japonisme of Unpredictable Complexity and Full-Color Ornateness

Lecture handout 2015.10.5, Architectural Juxtapositions, p.30

Yasutaka Aoyama

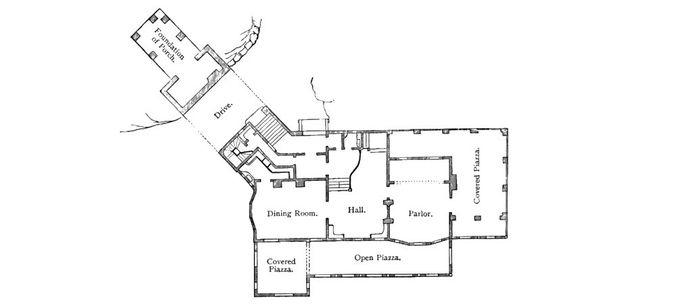

"The style of architecture dubbed Queen Anne was Japanesque in a different way. Here the move away from the traditional rectangular box, a standard of Western housing for centuries, was finally taken to its logical extreme. ... Think of the controlled-accident effect in the design of Japanese ceramics or the conspicuous avoidance of repetition in most Japanese arts, and you can see how the Japan idea relates to American Queen Anne architecture. It is especially apparent in the work of the architect Stanford White and the firm of Peabody and Stearns. The Opera House built in Norfolk, Connecticut, in 1883 and the Goodwin Building, a mix-use office and apartment complex built for Francis and James Goodwin in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1881... are rich in Japaneseque detail. ... The Japan craze affected the look of rural villages throughout New England through the growing popularity of new architectural forms, such as libraries, opera houses, and town halls."

William Hosley, The Japan Idea: Art and Life in Victorian America (1990, p. 105)

The Queen Anne style in the United States is often characterized as an eclectic mix of cultural styles--which it is, and the Japanese element is blended into that mix so that it often goes unrecognized. But many of the features of the style--the bold exterior coloring, the ornamental pattern details, the prominent roofs and complex intersecting rooflines, the asymmetric floor plans, the bay windows and other protrusions from the exterior wall surface--are prominent features of Japanese architecture. Of particular importance in the Queen Anne style seems to be Japanese shrine architecture, such as the Nikko Toshogu shrine-masoleum, dedicated to the Tokugawa Shogun Ieyasu, in Tochigi, Japan. Nikko was an extremely popular site for western tourists and visiting artists in the late 19th century, and many praises and depictions of it followed. It has not however, been sufficiently recognized as an inspiration for the Queen Anne style in discussions of Japonisme.

It is certainly at least possible that it did have an influence upon the Queen Anne style; there is no question that Japanese architecture in general did, as Vincent Scully, in his classic The Shingle Style and the Stick Style, wrote, regarding the formation of the Queen Anne style and the general direction of American architecture in the late 19th century: "other sources of inspiration and direction also began to be explored; Japanese architecture, for instance, had an important influence." (revised edition, Yale University Press, 1971, p. 4)

Below is an example of that influence in the work of the architect Francis Kimball.

Regarding these kinds of carved or plaster moulded exteror decorations and panel work, Vincent Scully writes: "Queen Anne shingles, panel work, and open interior space were reinforced by the architectural influence of another country represented by wooden buildings at the Centennial: that is, Japan. The Japanese buildings, a 'Bazaar' and a 'Dwelling' were of frame construction with overhanging eaves, and their structural articulation in some ways recalled the American stick style. The American Architect wrote of the 'Dwelling,' 'A bird is handsomely carve in bas-relief on the wooden panel between the top of the front door and the overhanging porch.' This feature relates to Queen Anne decorative motifs, as, for example, to its carved barge boards and plaster panels." (The Shingle Style and the Stick Style, Revised Edition, 1971, p. 21)

Here we have focused upon the ornamental aspects of the Queen Anne style; we must add as a concluding note that this does not preclude other fundamental Japanese influences.

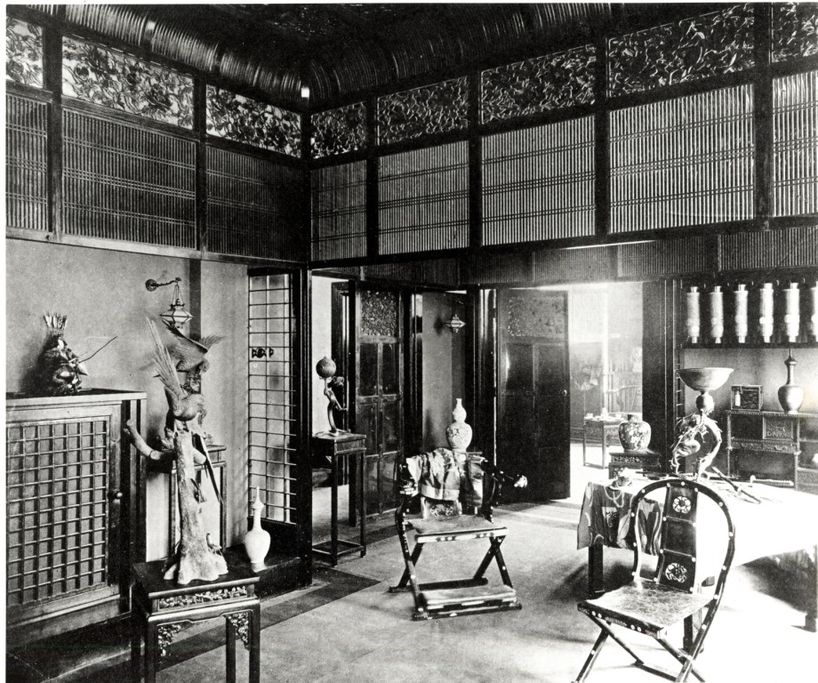

That influence extended to Queen Anne interiors, and is more apparent in contemporary writings of the 19th century. Take George Sheldon's description in his Artistic Country Seats---Types of Recent American Villa and Cottage Architecture (1886) of the Millbank House at Greenich, Connecticut, designed by architects Lamb and Rich---whose other designs, by the way, also exhibit Japanesque qualities: "The parlor, twenty by forty-four feet, is in Japanese style, in a deep-red lacquer, with a bamboo ceiling, and walls covered with Japanese embroidery. A semicircular bay-window is at one end of the room and an octagonal at the other. Standing at the mantel, which faces the entrance to the hall and is Japanese in spirit, you look across the parlor, across the hall, across the library, and across the dining-room, out of the latter's bay-window, and on to the lawn---an unusually extensive view." (p. 65)

This leads us to an even more critical point: the influence of the Japanese free and flexible floor plan. As Scully comments on this topic, "More importantly, of Japanese interior spatial organization, the Architect stated: 'Thus at any moment any partition can be taken down, and two or more rooms, or the whole house, be thrown into one large apartment, broken only by the posts which marked the corners of the rooms. Doors and windows, as we use them, there are none.' Consequently, Queen Anne materials and general spatial direction received, by 1876, the support of influences from similar aspects of Japanese domestic architecture. These had already been allied, through comparable---though in Japanese hands more sensitive and integral---handling of the wooden frame, to the American stick style itself." (1971, p. 22)

________________________

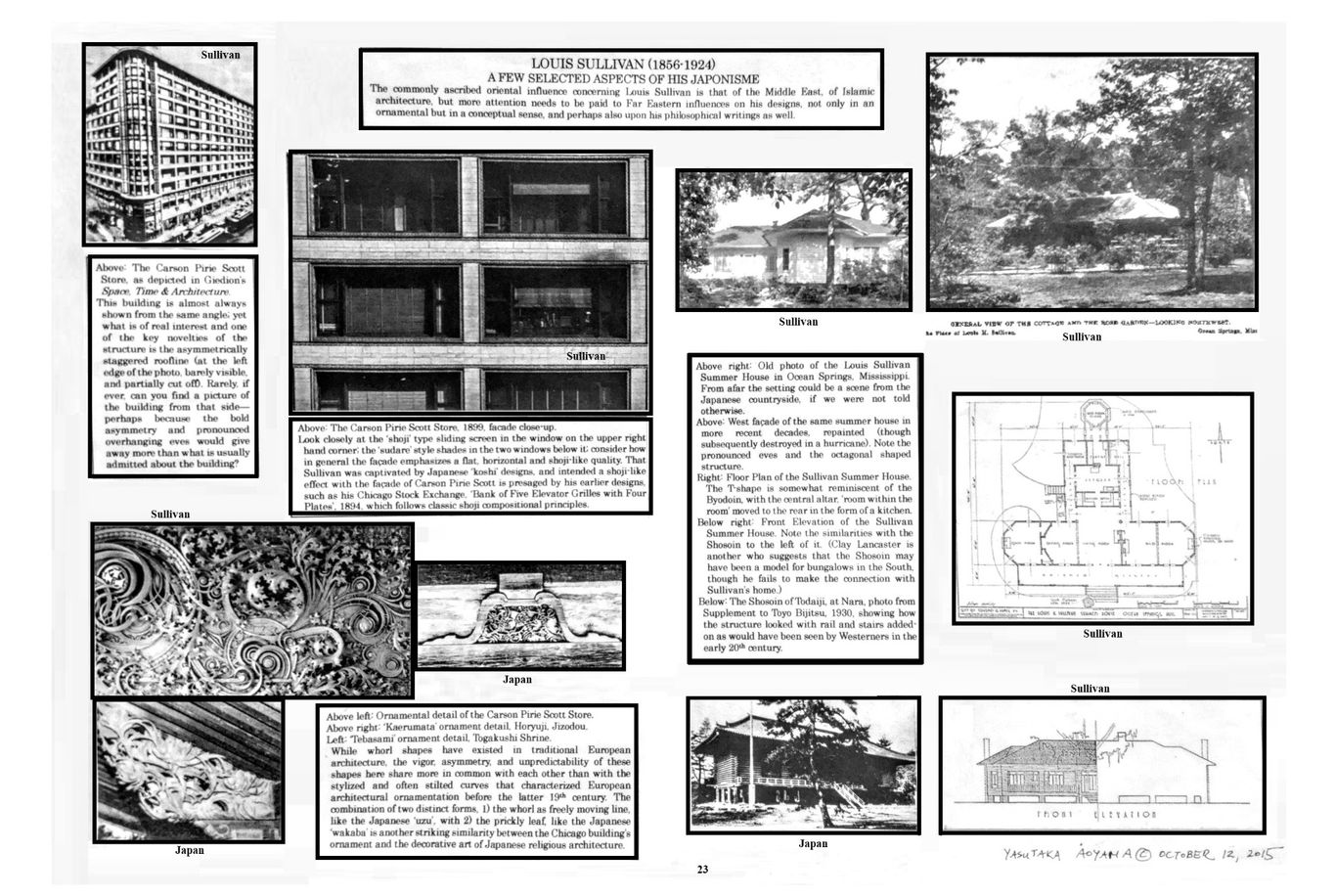

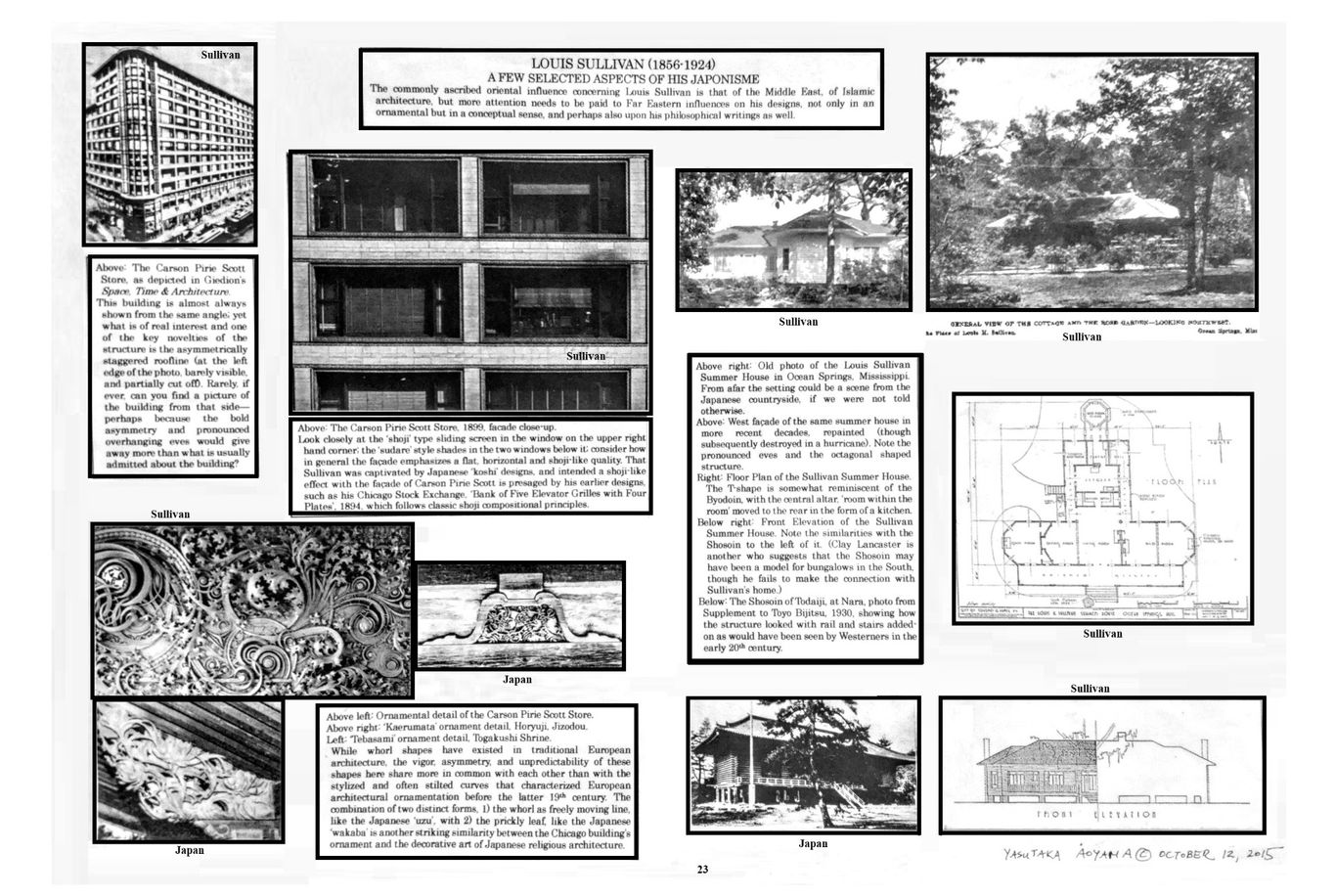

Louis Sullivan (1856-1924)

Selected Aspects of his Japonisme:

Perhaps more Japanese than Islamic in Style

Lecture handout 2015.10.12, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 28

Yasutaka Aoyama

There are definitely Islamic decorative elements in Louis Sullivan's designs, such as his National Farmers Bank (Owatonna, MI) interior, or his Garrick Theater (Chicago, IL) or his Prudential Building (Buffalo, NY) exteriors, among other works, as pointed out by biographers and architectural historians in terms of geometry, color, motif, and level of intricacy. But a key characteristic of most Islamic art, even floral art, is symmetry and a sense of perfect balance. However there are less tame and more wildly asymmetric lines in Sullivan's designs, and also a great amount of near full sculptural relief, that is alien to the Islamic tradition and much closer in spirit to the type of ornate Shinto religious architecture (with carvings by master sculptors such as Ishikawa Uncho), that was to be found flourishing in every region of Japan from the 18th century onward.

Therefore, given his blend of Islamic and Japanese aesthetic qualities, his ornamental style, might be described as 'Islamo-Japanese', though leaning more heavily toward the Japanese in form and spirit. That Sullivan was interested in Japanese design is testified by the fact that he had several books on Japan and Japanese art, and that furthermore, he occasionally asked Frank Lloyd Wright, who worked for him, to bid at auctions on his behalf for Japanese art objects (Sullivan bio by Yamabana Nami, in Katagami Style, 2012, edited by Mitsubishi Ichigokan Museum et. al., supervised by Mabuchi A, et. al.)

A few further comparisons between Sullivan's designs and those of Japan (and China) follow the lecture handout immediately below.

Below: Japanese shrine and festival wagon carvings compared with exterior detail of Sullivan Center, Chicago (center)

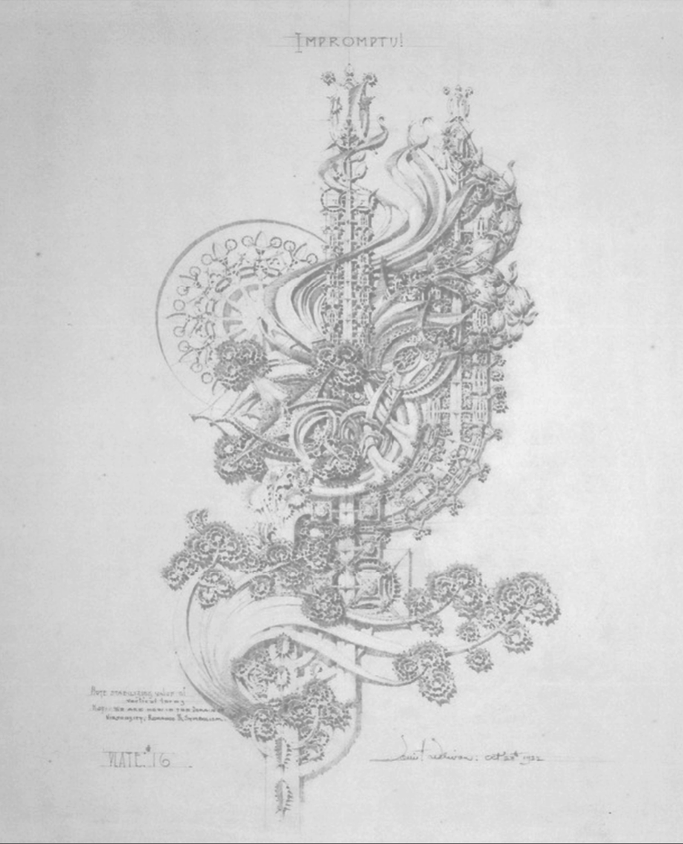

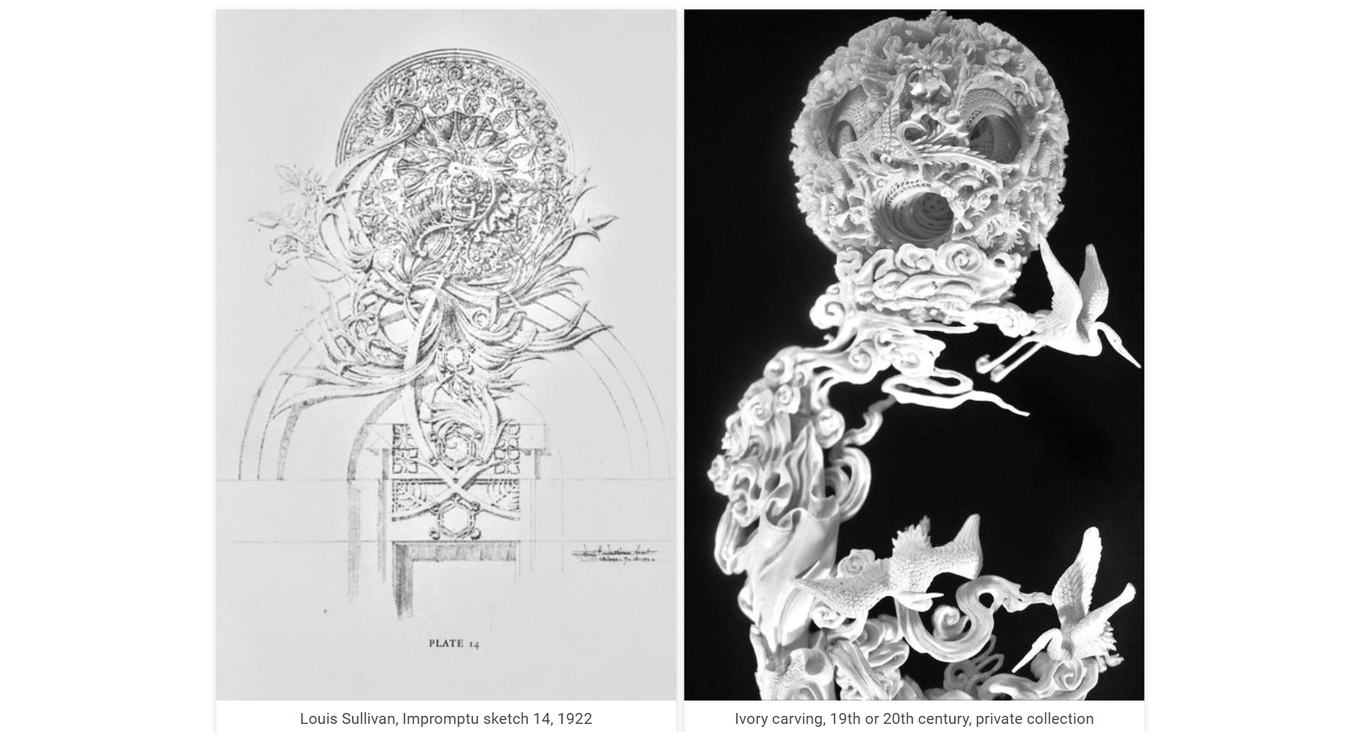

Below left: Louis Sullivan sketch 16 of 'Impromptu' (1922). Right: Japanese eave carvings (19th century)

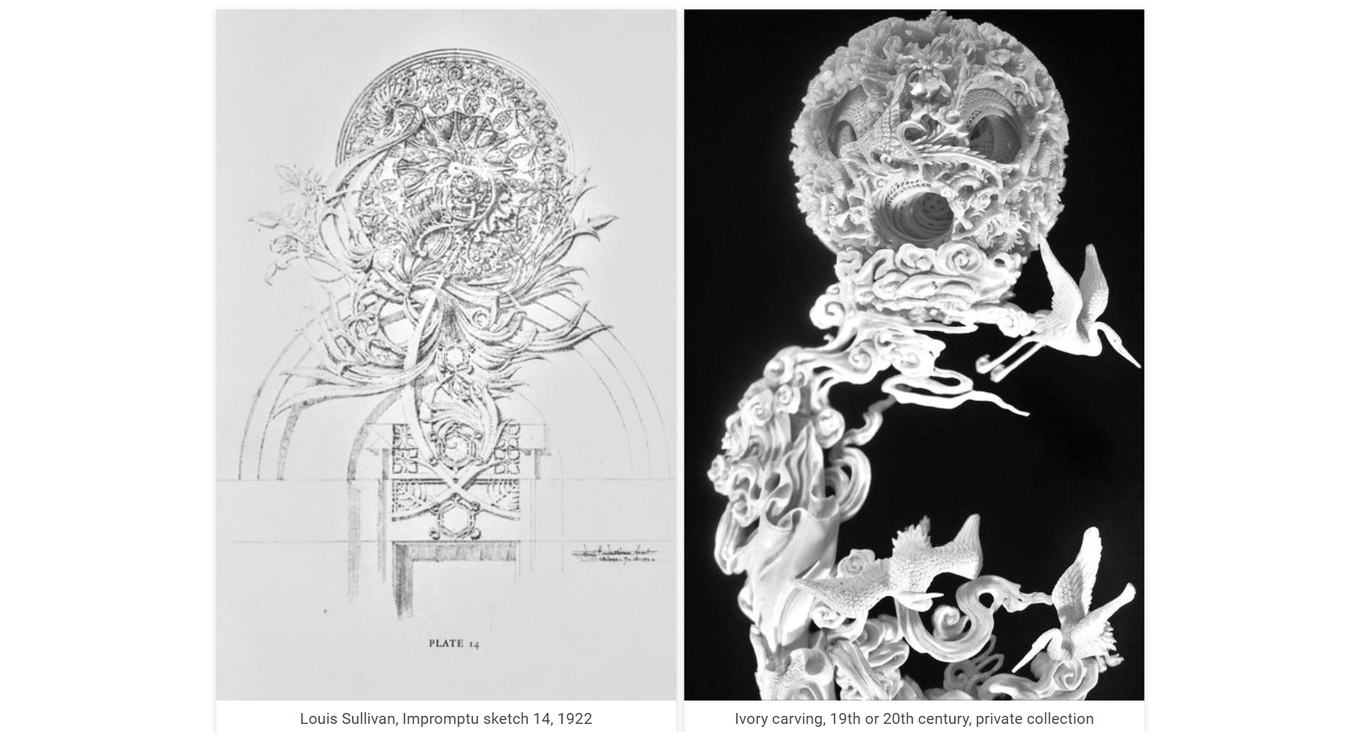

Below left: Louis Sullivan sketch 14 from 'Impromptu'. Right: Chinese style ivory carving, Japanese private collection, 19th or 20th century. Done in a style well developed by the mid 19th century, these intricate balls are known as a form of Chinese craftsmanship, but numerous pieces of the most elaborate kind are held in Japanese collections. Those at the National Palace Museum of Taiwan are the best known.

________________________

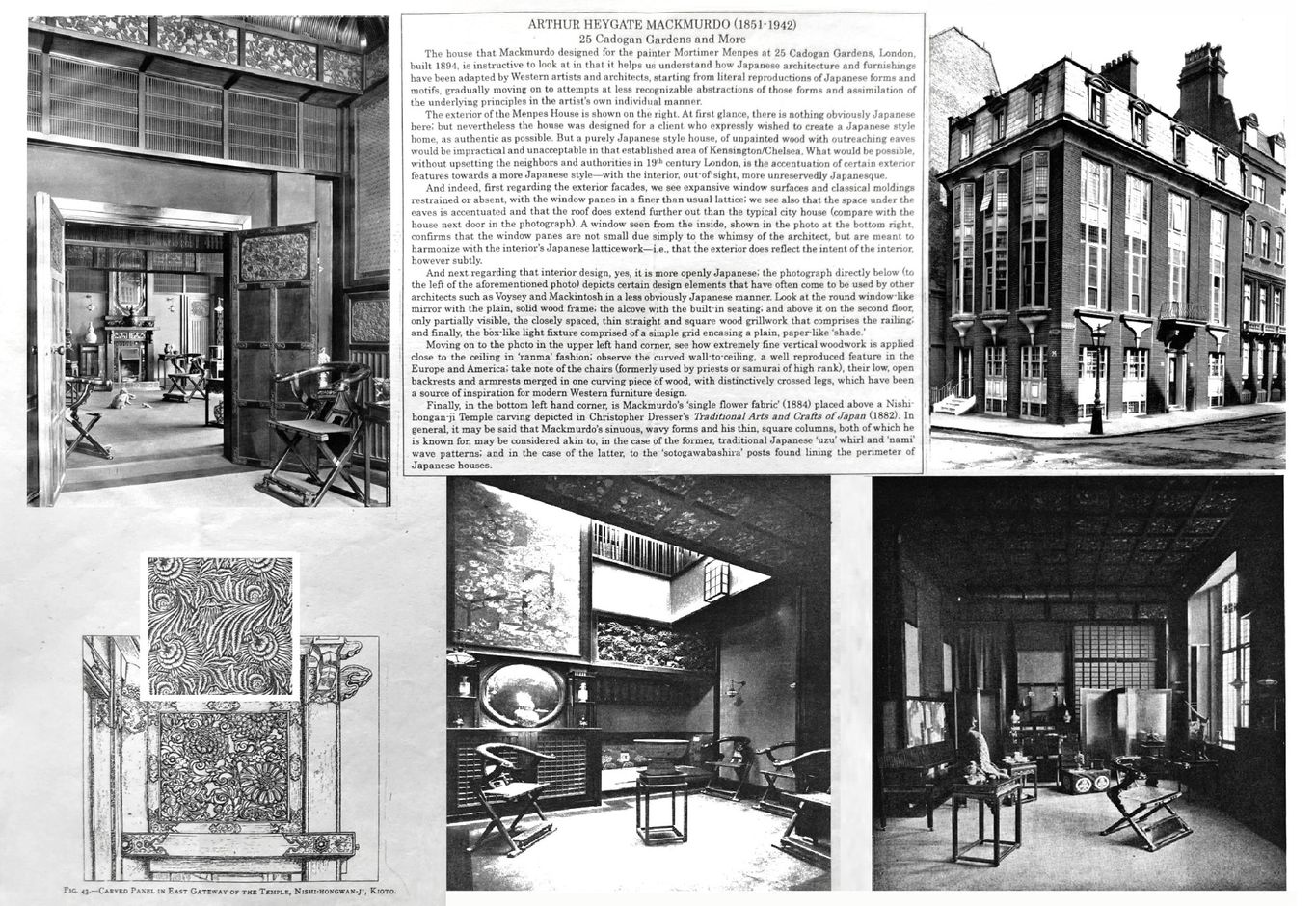

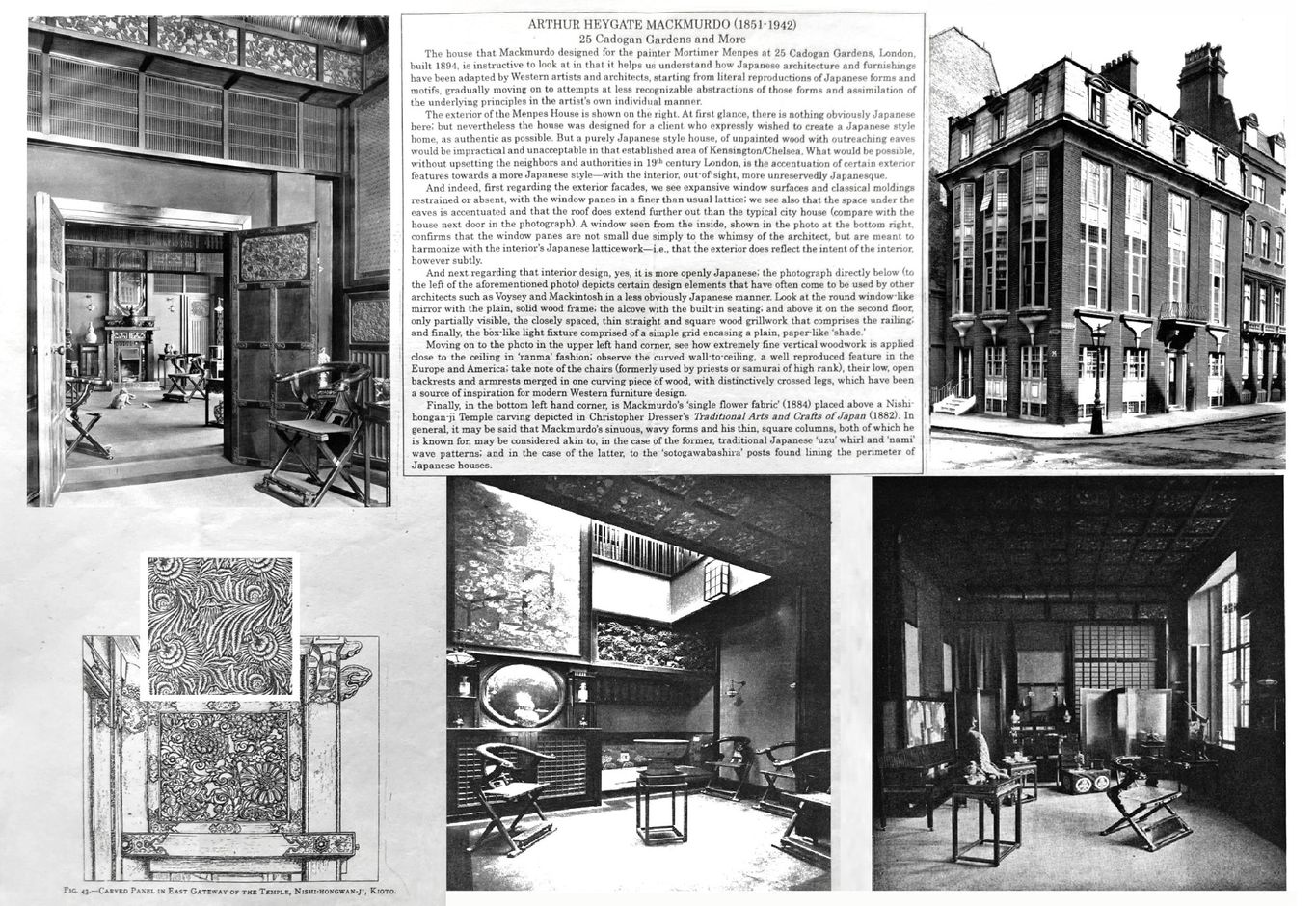

Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo (1851-1942)

Japonisme in a Pioneer of Art Nouveau

Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 29

Yasutaka Aoyama

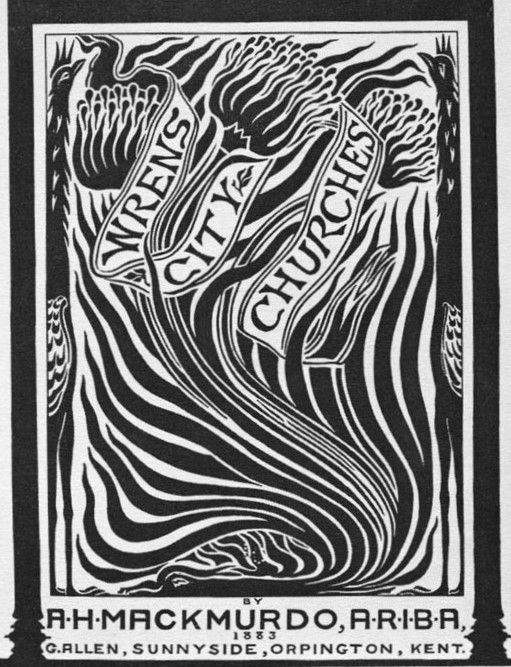

Arthur Mackmurdo's early designs such as his cover for Wren City Churches or Hobby Horse are considered precursors to the 'Art Nouveau' style. His characteristic thick wavy lines are of a type very much characteristic of ukiyo-e use of line found in woodblock prints. In Japan, from the earliest of times, reaching back to Jomon prehistory and carried on into the Edo period up to the 19th century, the bold and unpredictably curving line, whether representing water, fire, tree branch, wood grain or smoke has been a favorite theme for artists, cherished for its qualities of 'iki (stylish verve) and 'ikioi' (lively momentum).

Robert Schmutzler, one of the foremost historians of Art Nouveau, writes of the web of relationships that existed among artists involved with that movement, and the thread of Japanese design that was woven into it:

“Just as between Whistler and Rossetti, there also existed a relationship between Mackmurdo and Whistler and the Japanese style, and another one between Mackmurdo and Morris and the Pre-Raphaelites.” ---Schmutzler, Art Nouveau, 1977 abridged edition, p. 40.

.

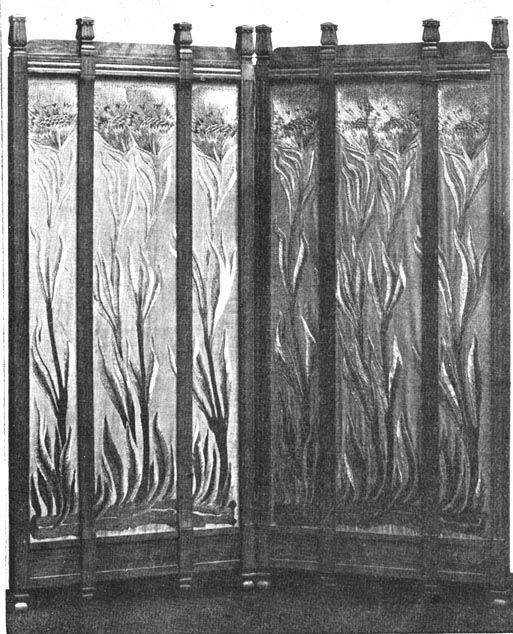

Below left, a Japanesque folding screen by Mackmurdo, 1884, and right, another image of the Mackmurdo designed Mempes house. Scanned images by George P. Landow, at victorianweb.org and The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, at rbkclocalstudies.wordpress.com.

Below, 1st row: Mackmurdo's cover for the book Wrens City Churches with waving vegetation filling the picture from end to end (left), and a tryptych center panel of Mackmurdo's depicting wavy flames (right).

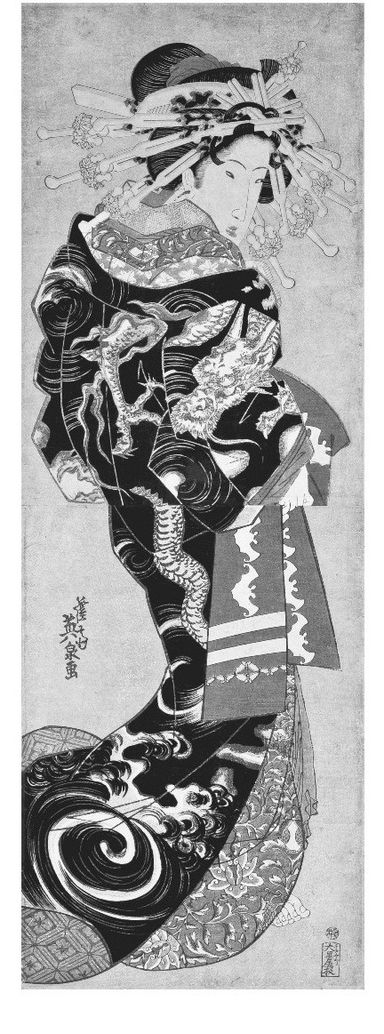

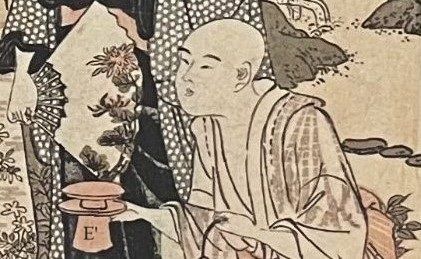

An Utagawa Kuniyoshi woodblock print of kabuki actors. The dynamic waves of billowing smoke are the real interest of the print, rather than the actors in front, which rise up and transform into Mackmurdo's wavy lines. This print is but one example of the Japanese genre depicting a variety of forceful waves and lively curves.

________________________

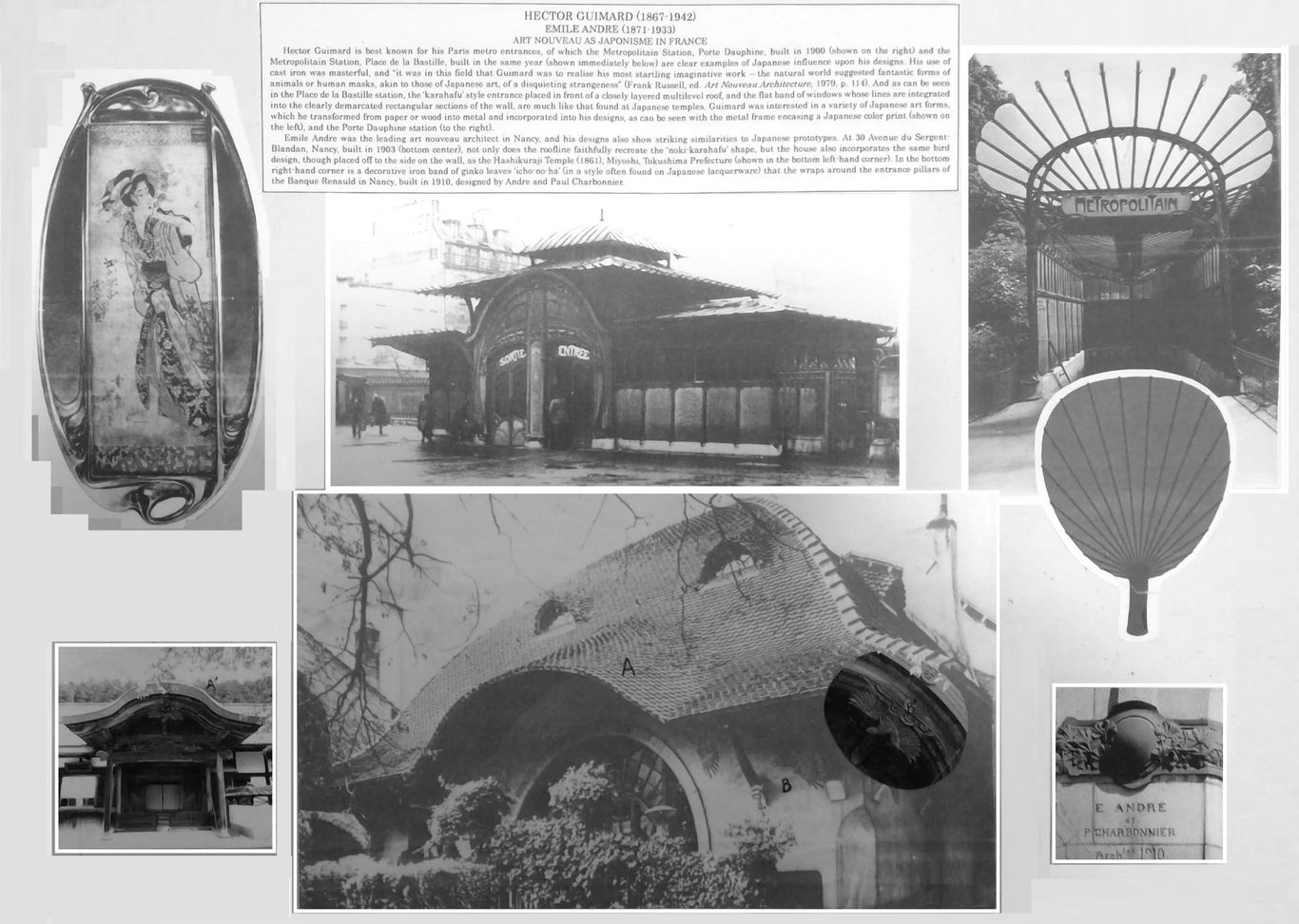

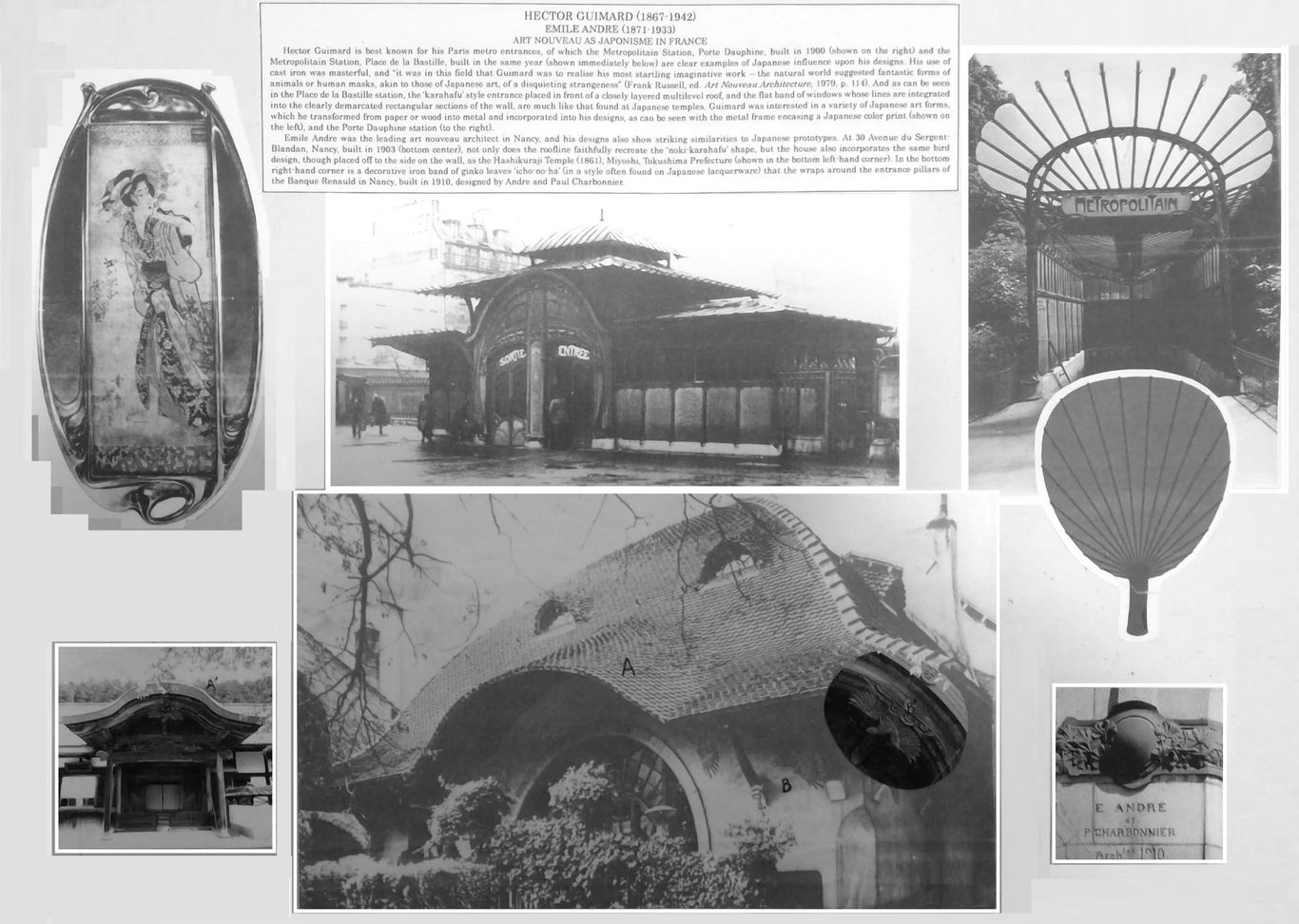

Hector Guimard (1867-1942)

Émile André (1871-1933)

Followed by brief comments on Henri Sauvage (1873- 1932),

Lucien Weissenberger (1860-1929), and Paul Charbonnier (1865-1953)

Art Noveau as Japonisme in Paris and Nancy

Lecture handout 2015, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 31, comments added 2023 August

Yasutaka Aoyama

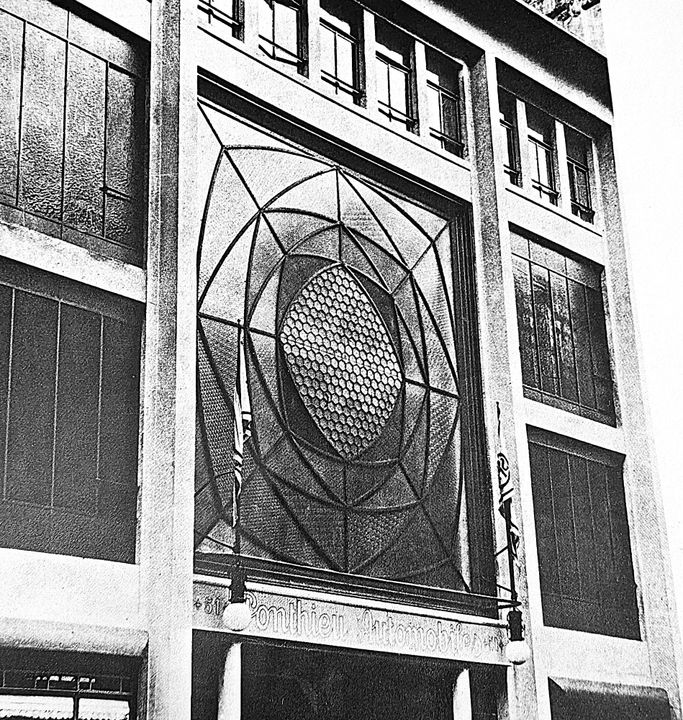

Hector Guimard is well-known for his Paris metro entrances, of which the Metropolitan Station, Porte Dauphine, built in 1900 (shown top right) and the Metropolitan Station Place de la Bastille, built in the same year (center top) are fine examples of his work showing clear indications of Japanese influence.

His use of case iron was masterful, and "...it was in this field that Guimard was to realise his most startling imaginative work---the natural world suggested fantastic forms of animals or human masks, akin to those of Japanese art, of a disquieting strangeness..." (Frank Russell, ed. Art Nouveau Architecture, 1979, p. 114).

And regarding one of Guimard’s celebrated architectural designs, the Castel Béranger, Robert Schmutzler, perhaps the foremost authority on Art Nouveau, writes that it was clearly Japanese art that was the driving force behind it:

“The most remarkable detail of the Castel Béranger consists in the surprisingly freely conceived asymmetrical ironwork of the main entrance, where Rococo blends with flamboyant Gothic. However, the decisive force, the stimulus that sets everything in motion, again springs from the flowing lines of the curves of Japanese woodcuts in particular and Japanese surface ornamentation in general. In the application of the characteristic features of these smooth and gliding lines, Guimard outshines even Horta, whose furniture basically appears knotted and cramped as if riveted together.” (Schmutzler, Art Nouveau, 1977 abridged edition, p. 100)

The Place de la Bastille station's 'karahafu' style shaped entrance, with its roof extending from a closely layered, multilevel roof, and the flat band of windows whose lines are integrated into the clearly demarcated rectangular sections of the wall, are reminiscent of Japanese temples (though the design seems to incorporate aspects of Nepalese religious architecture as well). Guimard was interested in a variety of Japanese art forms, which he transformed from paper or wood into metal and glass, thus incorporated them into his designs, as can be seen with the metal frame encasing a Japanese ukiyo-e print (top left), and the 'uchiwa' fan style roof, made of metal and glass jutting out over the Porte Dauphine station entrance (top right).

Below: Close up of Hashikuraji Temple in Tokushima prefecture with a typical carved bird with wide spread wings under a karahafu entrance (left) and the Emile Andre designed house in Nancy with an extremely similar painted bird under a karahafu style arched entrance roof (middle), with a close up of Andre's bird design with the Japanese example inset (right). Unfortunately, Andre's lovely japoniste bird design has disappeared--white washed--simply painted over. As in so many cases of famous works of architecture, traces of Japanese influence are eradicated by later generations, less cosmopolitan.

Nancy as a Center of Japonisme

(The following text and illustrations added August 2023)

It seems Nancy was a particularly active center of japonisme, especially among the architectural community there. The famous Henri Sauvage (1873-1932), also an architect at Nancy during this time, reveals an underlying Eastern inspiration in various aspects of his design for Villa Majorelle (1902). His prominent and multiform gables, and the loggia on the west facade for instance, suggest Japanese influences that had already been at work in the Stick Style in America decades earlier (see the following section on the Stick Style).

Japanese forms can also be seen in Lucien Weissenberger (1860-1929), who collaborated with Sauvage on the Villa Majorelle, and designed a detached stone garden kiosk-like structure, which is topped with what distinctly looks like a Japanese-type parasol.

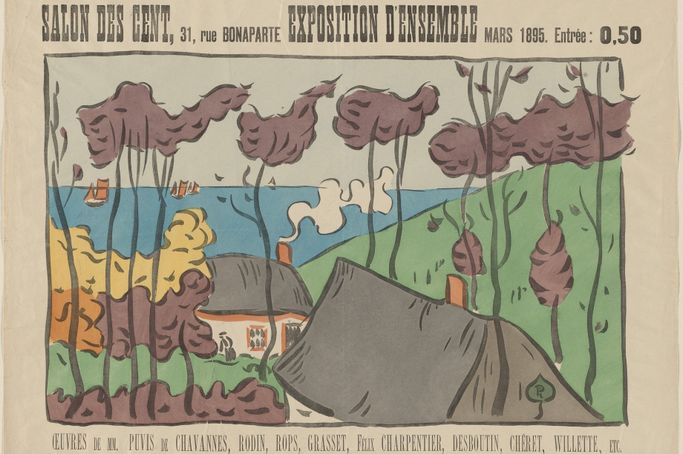

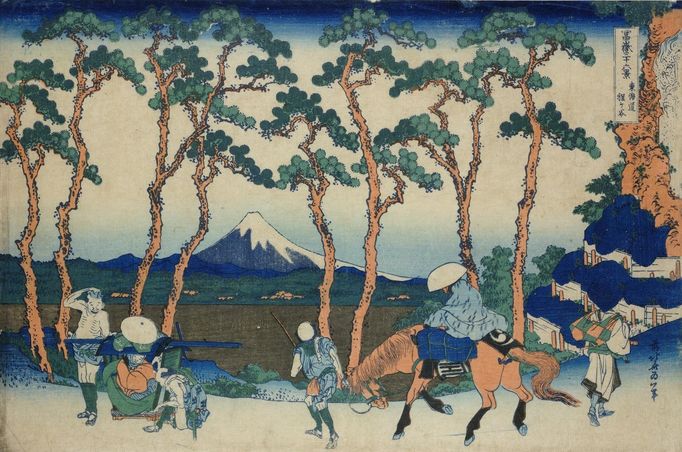

In the case of Paul Charbonnier, while his architectural designs show less prominent indications of Japanese influence, his other artwork, such as the poster below, is clearly in the japonisme style, following the example of Hokusai's famous print.

Paul Charbonnier's 'Salon des Cent, Exposition d'ensemble' (1895) Hokusai's 'Hodogaya on the Tokaido Road' (1832).

The following added 2024.9.15

That there was in Nancy a general and keen interest in Japanese art among those involved with design is suggested by the activity of those in other fields besides, but related to, architecture and interior design. As Robert Schmutzler writes:

“It was not in Paris but in Nancy that French Art Nouveau achieved its greatest independence, reaching the highest quality in the glassware of Emile Galle (1846-1904)). … In the South Kensington Museum [London], he was fascinated most of all by Japanese glassware displayed there after the World Exposition of 1862. Chinese and Japanese glassware, above all the coloring techniques used in and complicated method of production and inspired his artistic style. In Nancy (where he settled in 1874 and founded his own glassworks) Gallé later became acquainted with a Japanese student, who had come there in 1885 to study botany. …

... It is difficult to establish a chronology of the productions of his own workshop, so that we cannot distinguish with any certainty when his Art Nouveau period started and when he actually arrived at High Art Nouveau. But a Far Eastern touch can always more or less be felt and must certainly have already been noticeable in the works he sent in 1889 to the World Exposition in Paris. E. de Vogue writes about Gallé in his Remarques sur l’Exposition de 1889, 'Let us praise the whims of fate for having allowed a Japanese to be born in Nancy.' " (Art Nouveau, 1977 abridged edition, p. 97)

---Reflecting, by the way, not only the strong influence of Japan upon Gallé, but also just how much good design was associated with Japan by the aesthetically inclined readership in France at the time.

Unfortunately, as in many such cases, we are not given the name of the Japanese student who seems to have been instrumental in Gallé’s endeavors. Schmutzler writes also of Gallé‘s collaboration with Prouvé in Nancy, creating furniture pieces of elaborate marquetry; these too show aspects of Japanese marquetry and lacquerware design which Schmutzler seems unaware of, which he attributes solely to a Rococo resurgence. That aside, it seems clear that the example of Japan loomed large in the hearts of those at the forefront of design innovation in Nancy, in architecture, and the crafts which furnished it.

________________________

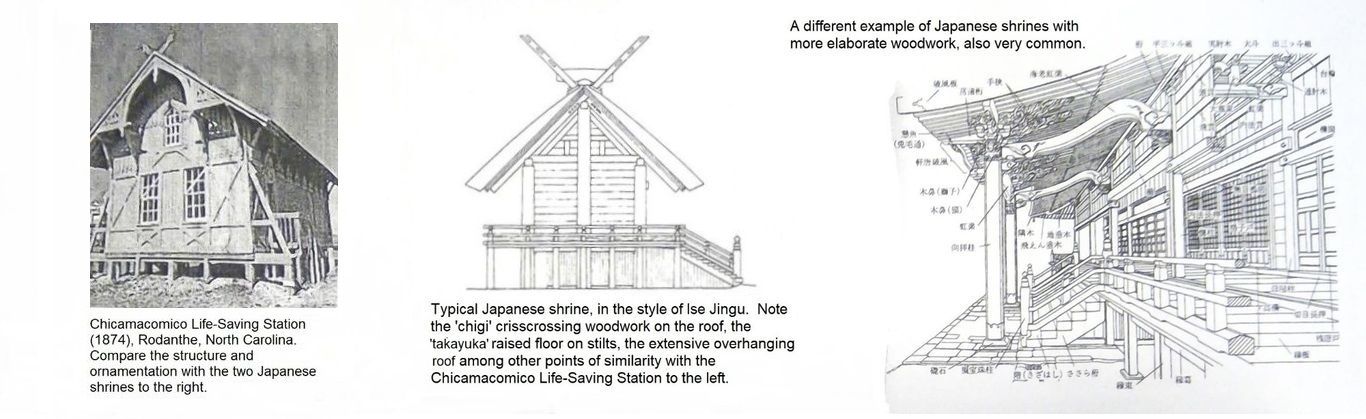

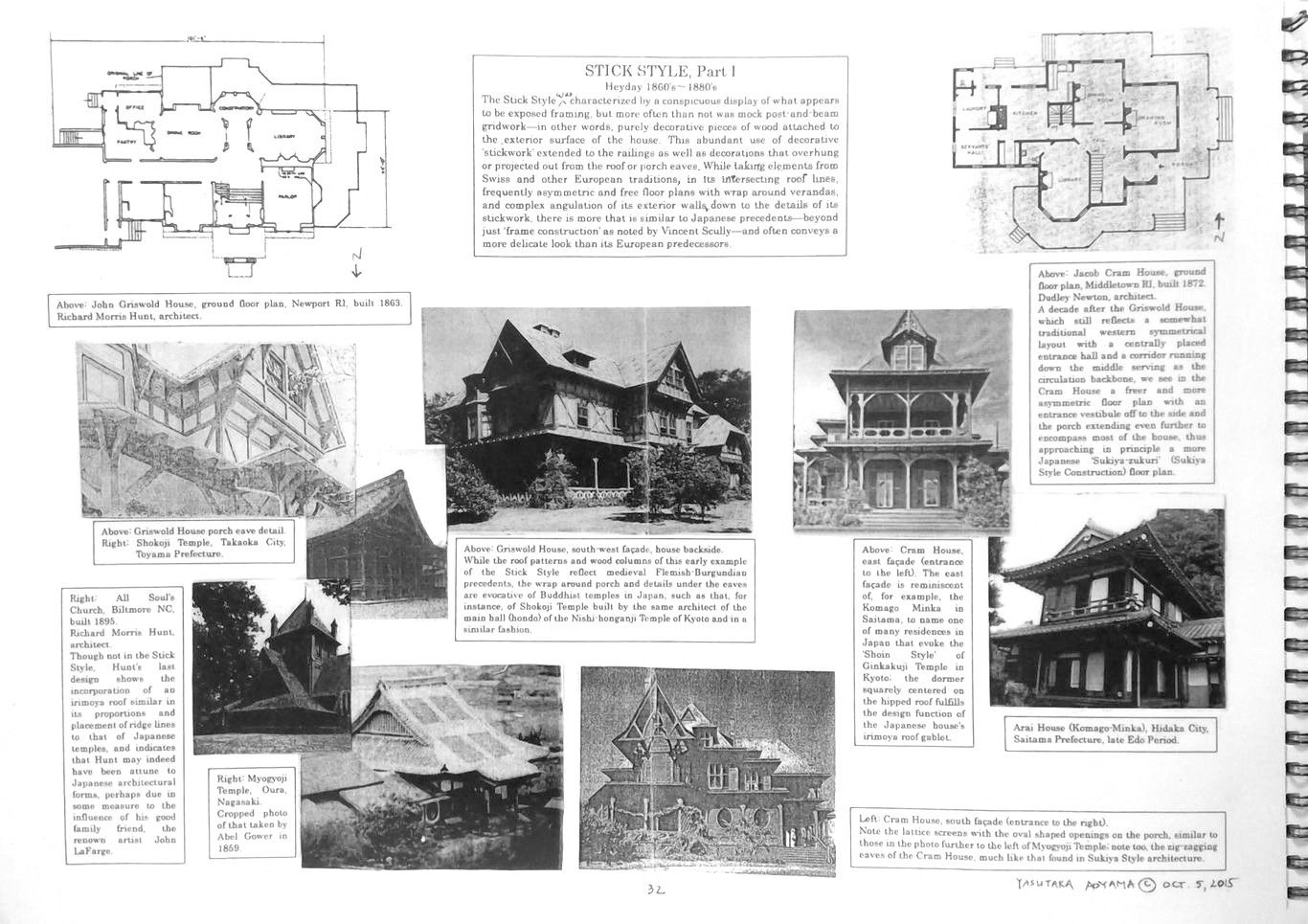

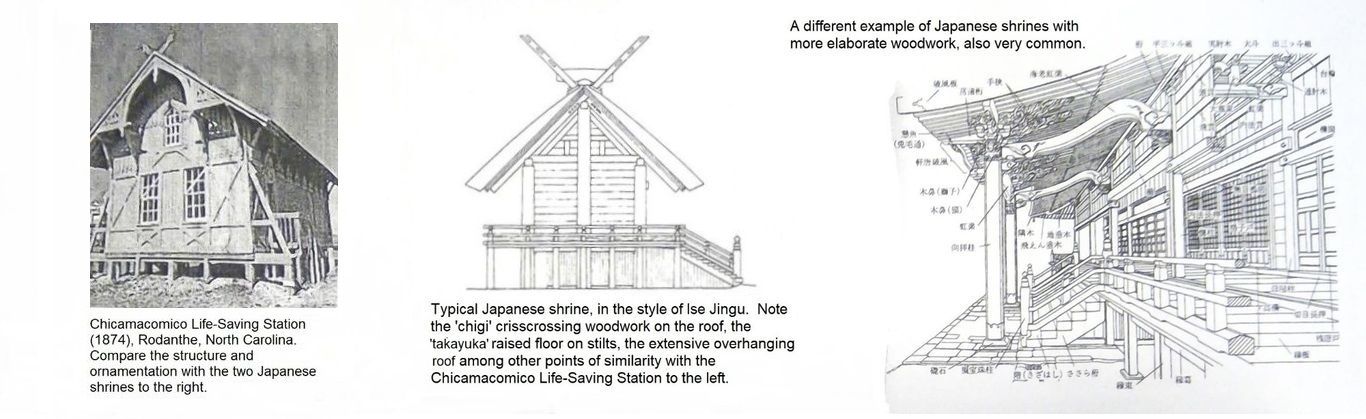

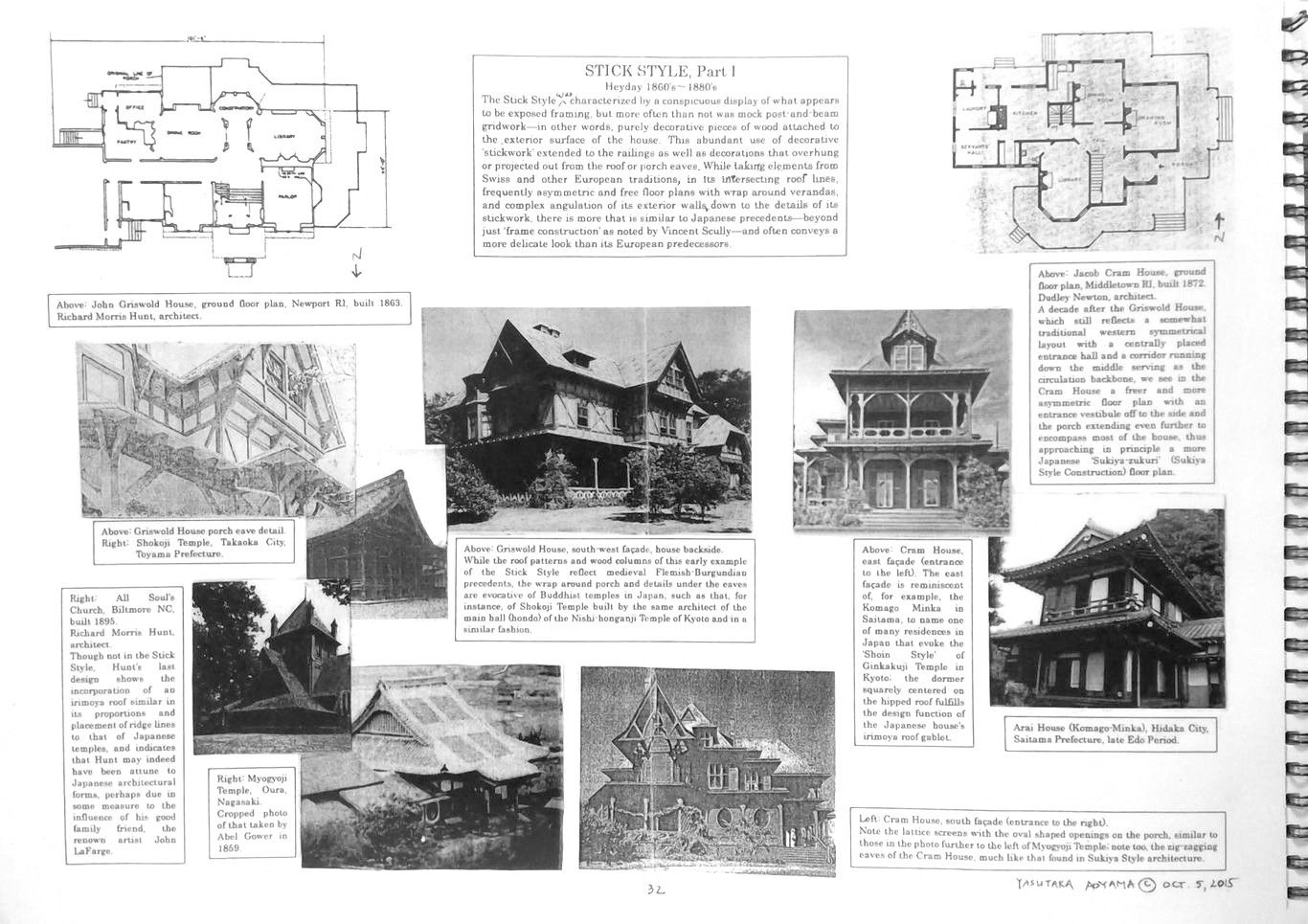

Stick Style, Part I

Incorporating Japanese Jinja (Shrine) Woodwork in American Style

Lecture handout 2015.10.5, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 32

Yasutaka Aoyama

"The Japanese pavilion in Philadelphia (at the 1876 Centennial Exposition) helped to stimulate a popular craze for things Japanese... At a deeper level its influence soon appeared in the American house in a predilection for the open plan, latticework, extended eaves, a craftsmanlike assembly of parts, and the integration of the building with its landscaped setting ... "

Frederick Koeper, American Architecture, Vol. 2: 1860 to 1976, MIT Press, 1983.

"Japanese influence in Victorian American architecture is demonstrated in the content of specific styles and in subordinate ornament, both inside and out. Most of all it was communicated through moveable furnishings and wall and window treatments, without which the architecture appears barren and confusing. One of the most intriguing arguments in favor of Japanese influence in American architecture is Scully's stick style, the most radical, modern, and explicitly American of the reform styles."

William Hosley, The Japan Idea: Art and LIfe in Victorian America, Wadsworth Atheneum, 1990.

Uploaded 2024.6.19

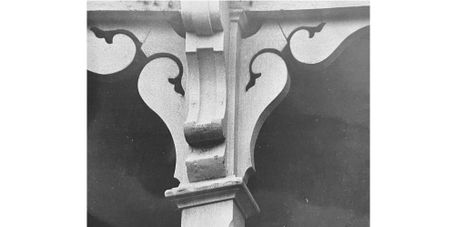

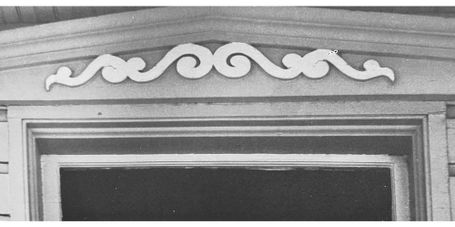

Japanese Motifs in Stick Style Ornament

The following photos of stick style ornament are from Ben Karp's Wood Motifs in American Domestic Architecture (1966), of exteriors dating from 1850-1900, from primarily the east coast of the United States, centered on New York State, though examples can be found across the United States. As Vincent Scully, one of the foremost authorities on the Stick Style wrote, ''the builders of the stick style broke with the grand styles of the past and absorbed influences from the comparable wooden styles of Switzerland and Japan.'' (The Shingle Style and the Stick Style, Revised Edition, 1971, p. 3)

True, Switzerland was a factor; but a look at the fine details of the more distinctive design characteristics of American stickwork points to the influence of Japan. Just as Japanese ukiyo-e awakened English artists and artisans to find comparable inspirational sources in gothic traditions closer to home but nevertheless mirroring Japanese designs and taste, so too, did American architects claim precedents in Swiss architecture, while in fact often incorporating specific patterns and decorative conceptions from Japan.

Text be added and individual photos to be captioned.

The Uzu and Wakaba Motif in the Stick Style

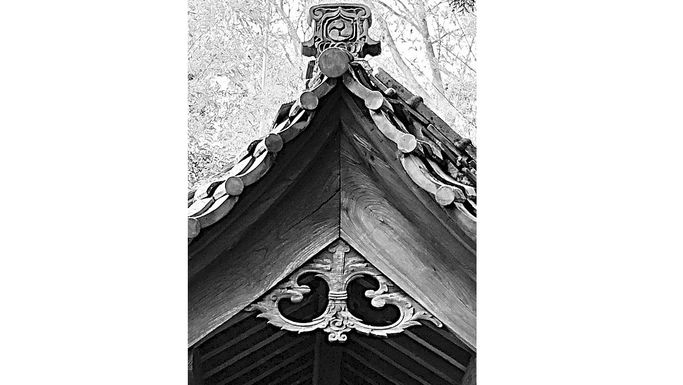

Examples of the Uzu Wakaba Motif in Japanese Shrine Eaves and Archways

Juxtapositions of the Stick Style and the Japanese Uzu Wakaba Motif

Stick Style Ranma-type Woodwork

Stick Style and Japanese Gegyo-type Gable Ornaments

Stick Style Design Elements from Japanese Temple/Palace Doorways to Eaves

The stick style reproduced various Japanese architectural forms freely on its exteriors; even gates and doors might be replicated on the facade of a building as in the example below left. The Daitokuji Temple karahafu-roofed mon (gate) is shown to the right for comparison. Sometimes there is a chrysanthemum emblem in the center panel of the temple gate doors, corresponding to the roundrel on the stick style facade, though not on the Daitokuji gate doors shown here. Nevertheless, the similarity is still quite apparent. The stick style facade includes other details of mon doors, such as the 'I' bar bracing boards situated between the three panels on each side.

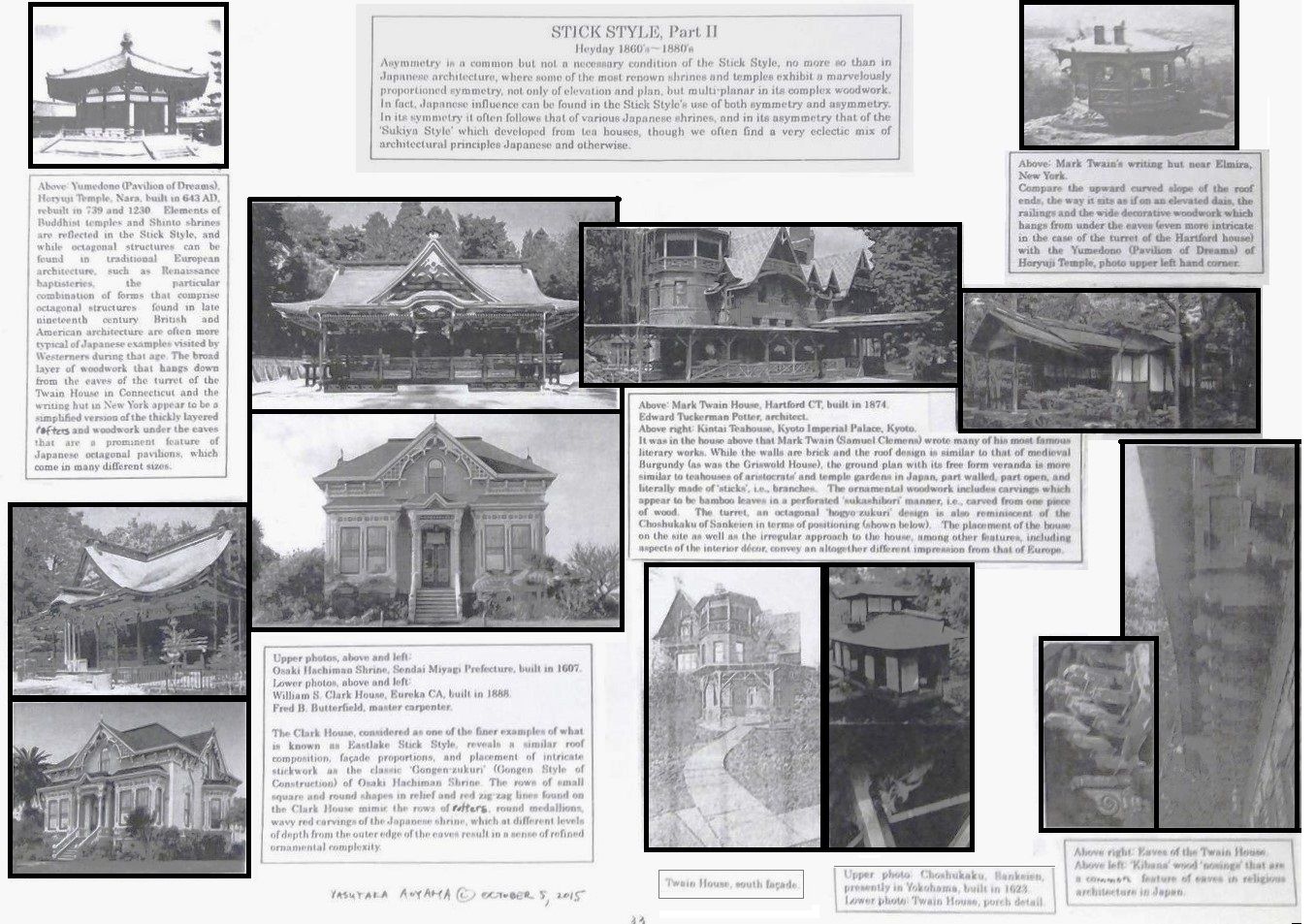

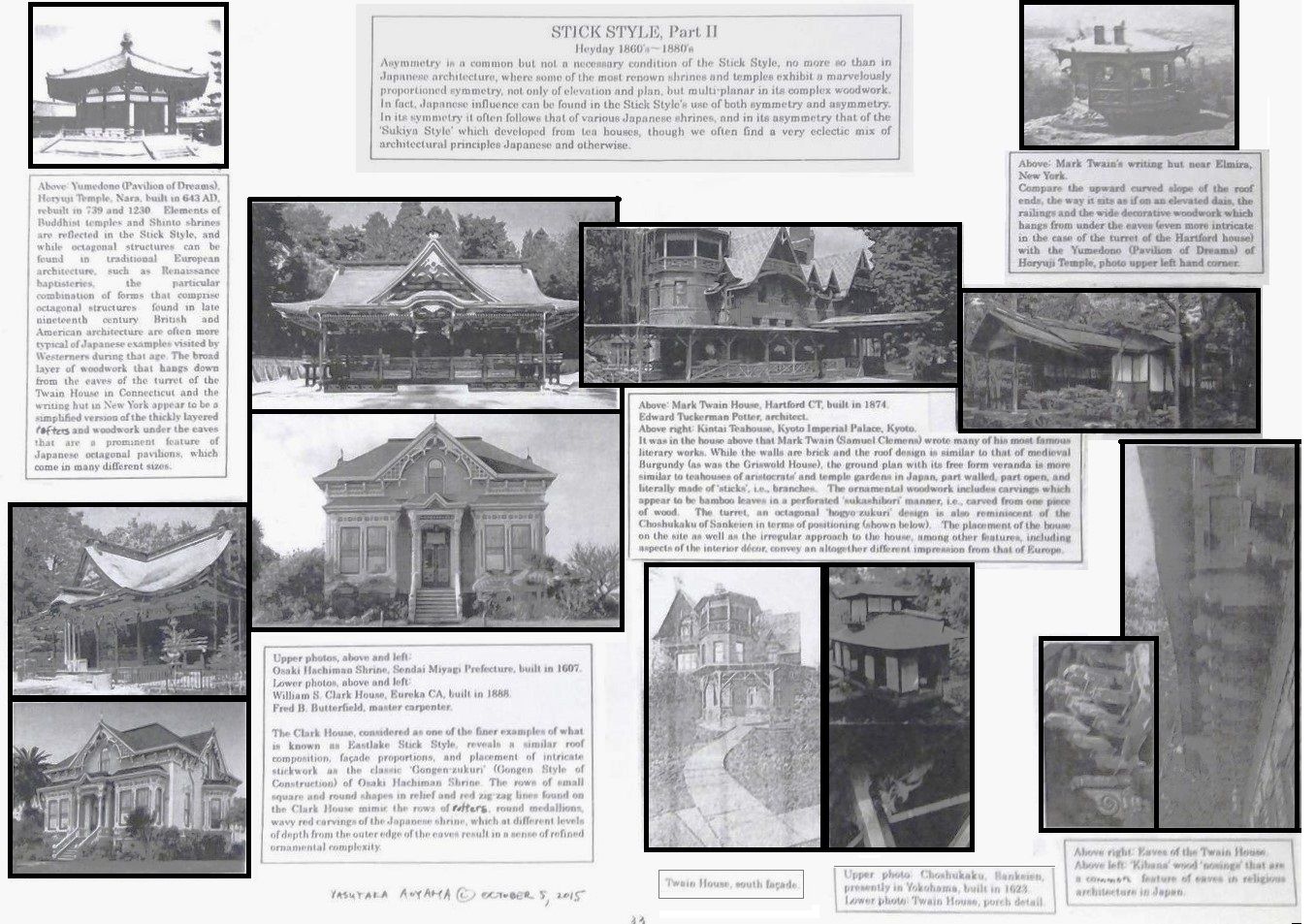

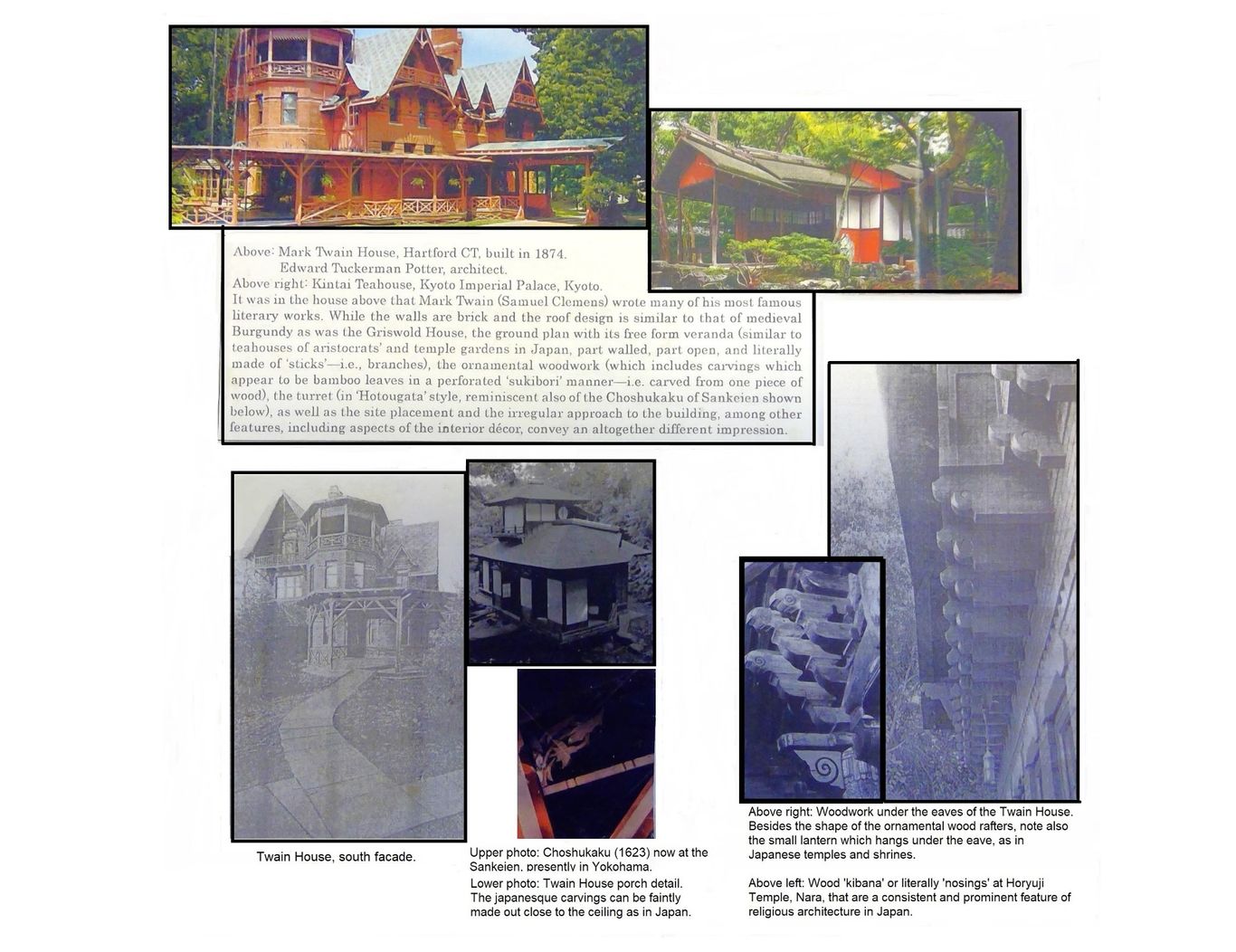

Stick Style, Part II

Incorporating Japanese Style Symmetry and Asymmetry into American Design

Lecture handout 2015.10.5, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 33

Asymmetry is a common but not a necessary condition of the Stick Style, no more so than in Japanese architecture, where some of the most renown shrines and temples exhibit a marvelously proportioned symmetry, not only of elevation and plan, but multiplanar in its complex woodwork. In fact Japanese influence can be found in the Stick Style's use of both symmetry and asymmetry. In its symmetry it often follows that of various Japanese shrines, and in its asymmetry that of the 'Sukiya Style' which evolved from tea houses; though we frequently find a very eclectic mix of architectural principles, Japanese and otherwise in Stick Style designs.

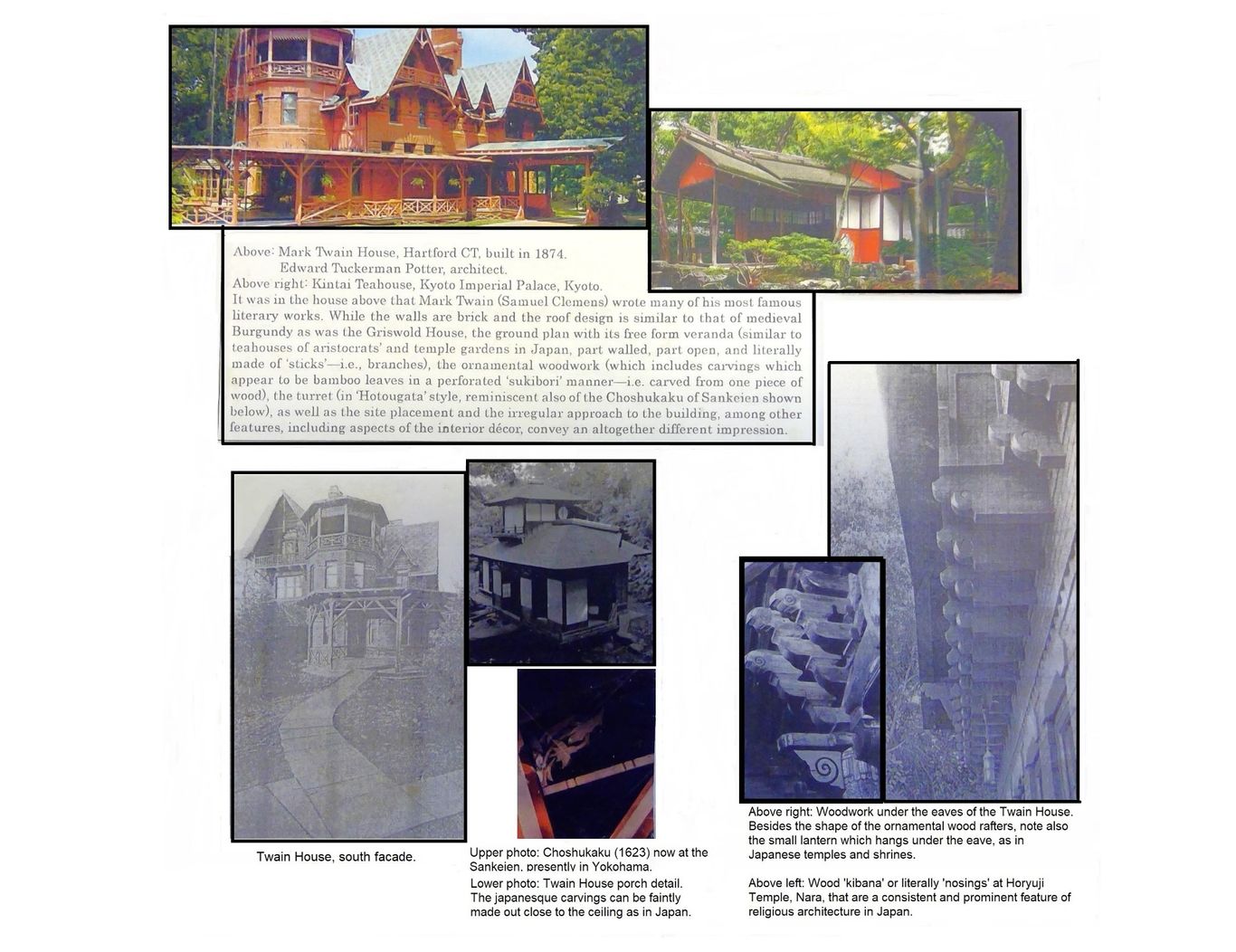

Sections on Mark Twain from Stick Style, Part II

Twain House Eave Details

Low sloped, extended eaves with taruki-like boards, ranma-like woodwork on wide open engawa or tsukimi type porches.

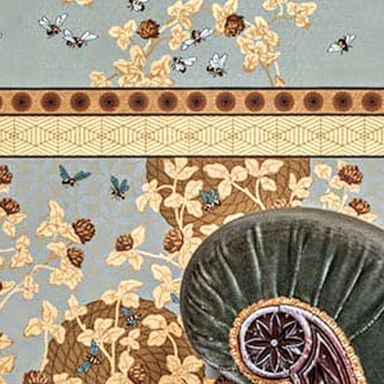

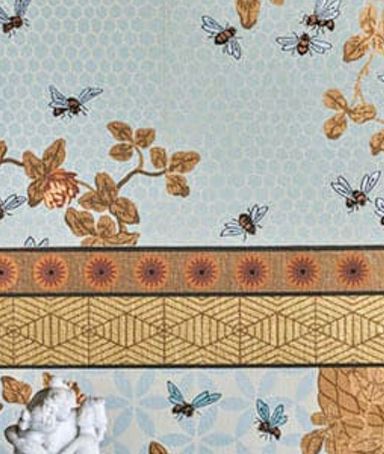

Katagami Patterns and Traditional Japanese Motifs throughout the Twain House

Restoration of the original wallpaper clearly shows the Japanesque influence in the decorative approach at the Twain House.

Japonaiserie objects scattered throughout the Twain House

Typical mid-19th century style Japanese cloisonné and wallpaper designs as well as Japanese temple-reminiscent carvings of the fireplace mantle, blend with classical figures, paintings and books.

Japonaiserie in the Indoor Garden/Greenhouse of the Twain House

Note in this old photo how numerous oriental objects some Japanese and others possibly Chinese, were nonchalantly placed here and there in a very eclectic style: Japanese chochin lanterns above, and a frog on the rim of the indoor pond below, porcelains in cabinets and on a Chinese style displaying stand, mixed with classical Greco-Roman style sculptures. Among the indoor plants, it looks as if there are some of Japanese origin, such as the morning glory (朝顔)and aspidistra (ハラン). Alongside the japonisme of Japanese visual and plastic arts, was a well-documented interest and importation of Japanese plant varieties and gardening ideas, including philosophical / poetic concepts associated with them. See for instance, Hashimoto Yorimitsu, 'Asagao wo meguru eigoken no japonisumu---gadeningu kara zen made' [The japonisme of the morning glory in anglophone countries---from gardening to Zen] in The Japonisme Association edited Japonisme Reconsidered: The Other and the Self in Representations of Japanese Culture, Tokyo: Shibunkaku Publishing, 2022.

This caption uploaded 2024/3/17.

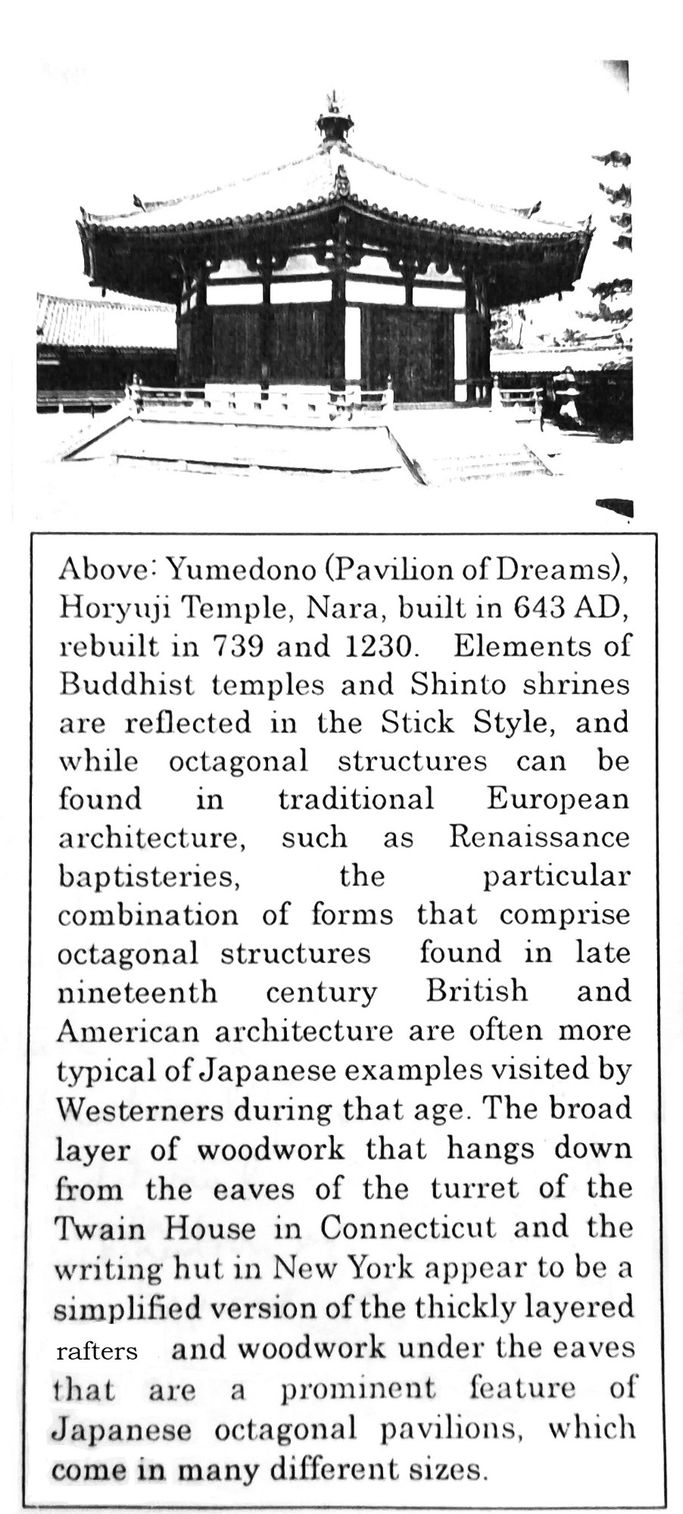

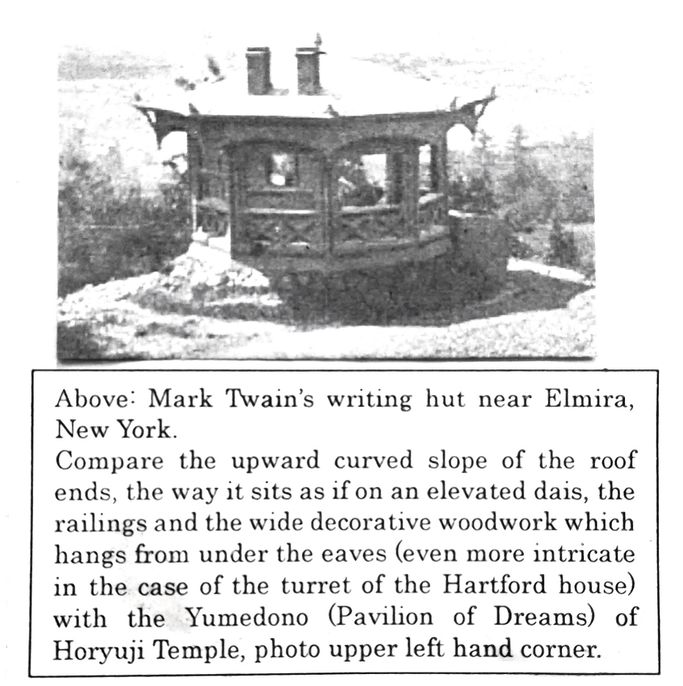

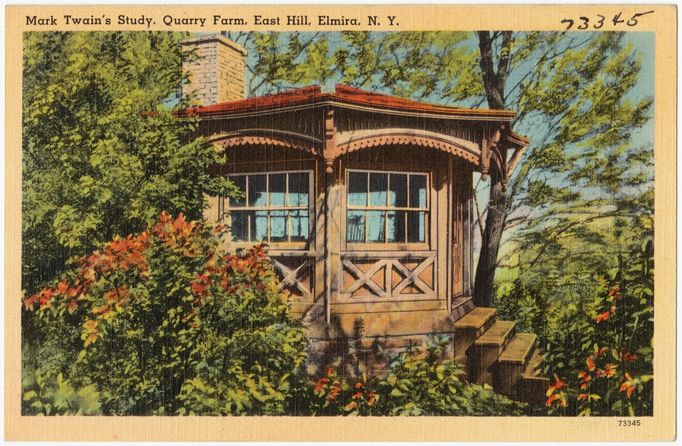

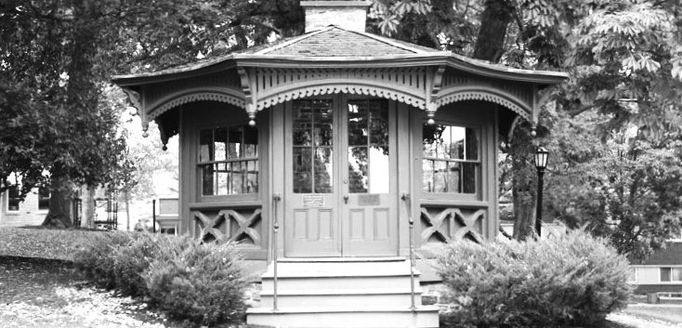

The Yumedono of Horyuji Temple, Nara, and Twain's writing hut in Elmira, New York

The top and middle (postcard) photos on the right show the hut in its original location on Quarry Farm in Elmira, New York, with splendid views of the surrounding countryside. The last photo shows it in its present location on the campus of Elmira College in Elmira, New York.

________________________

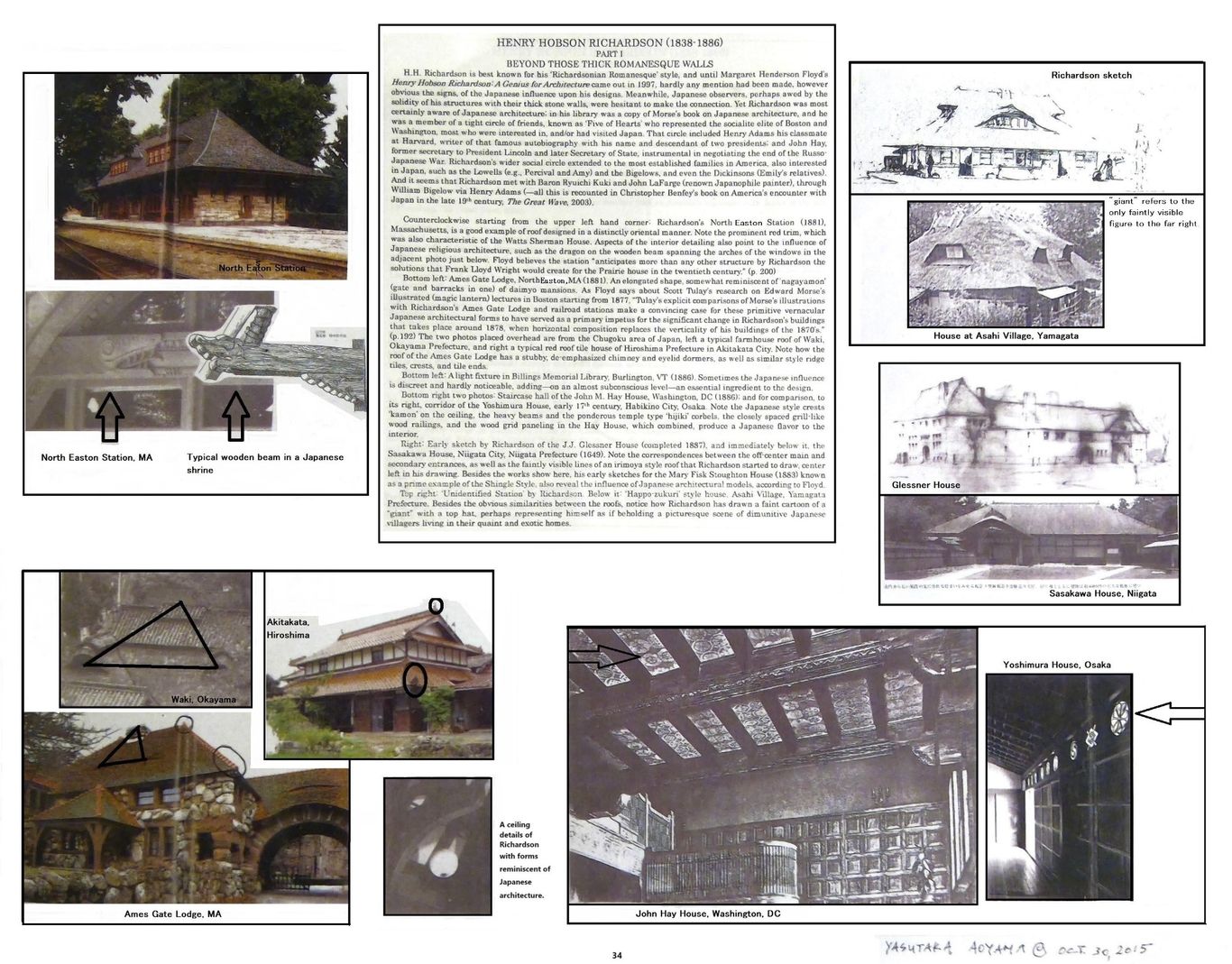

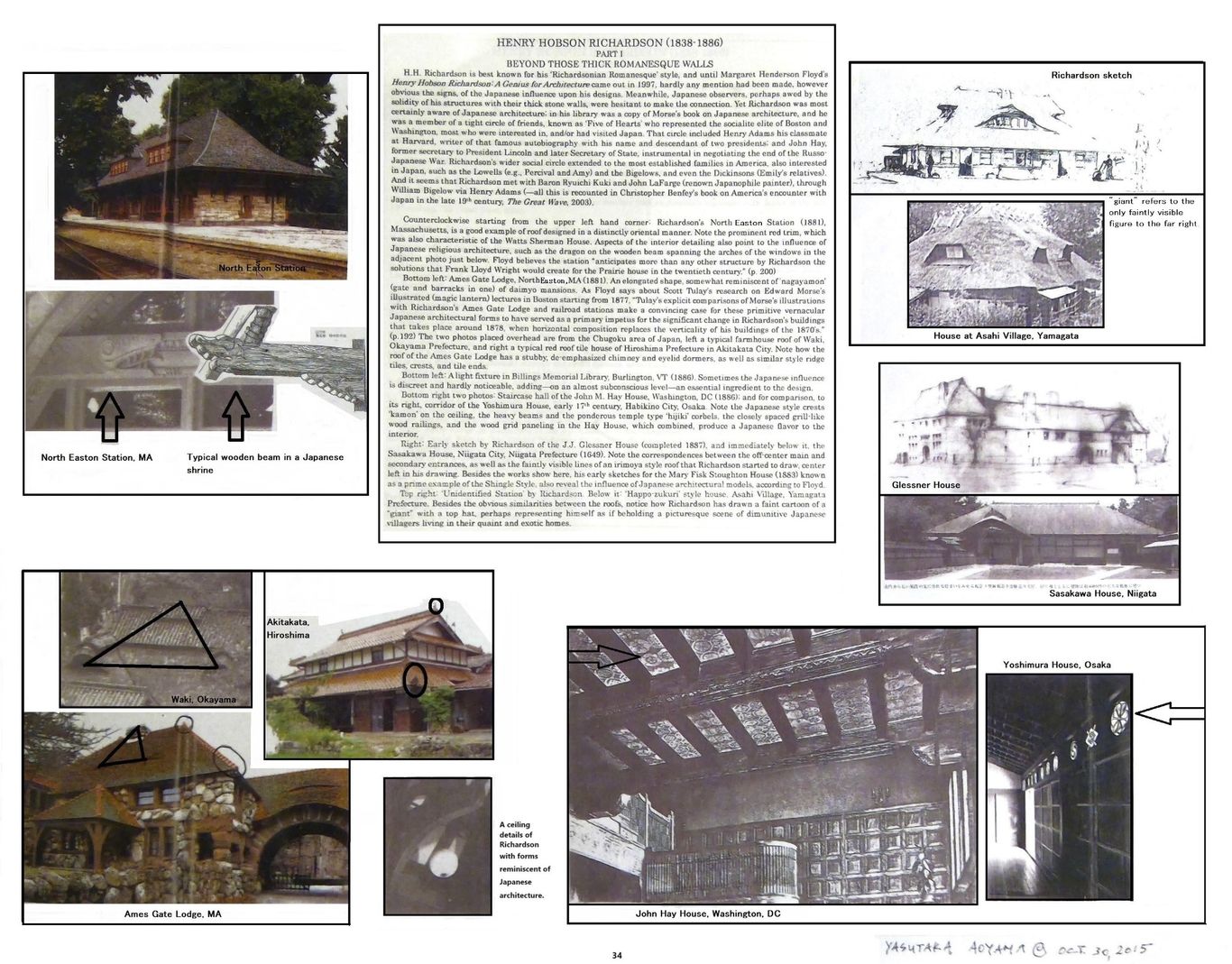

Henry Hobson Richardson (1838-1886)

Part I: Beyond those Thick Romanesque Walls

Lecture handout 2015.11.5, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 34

Yasutaka Aoyama

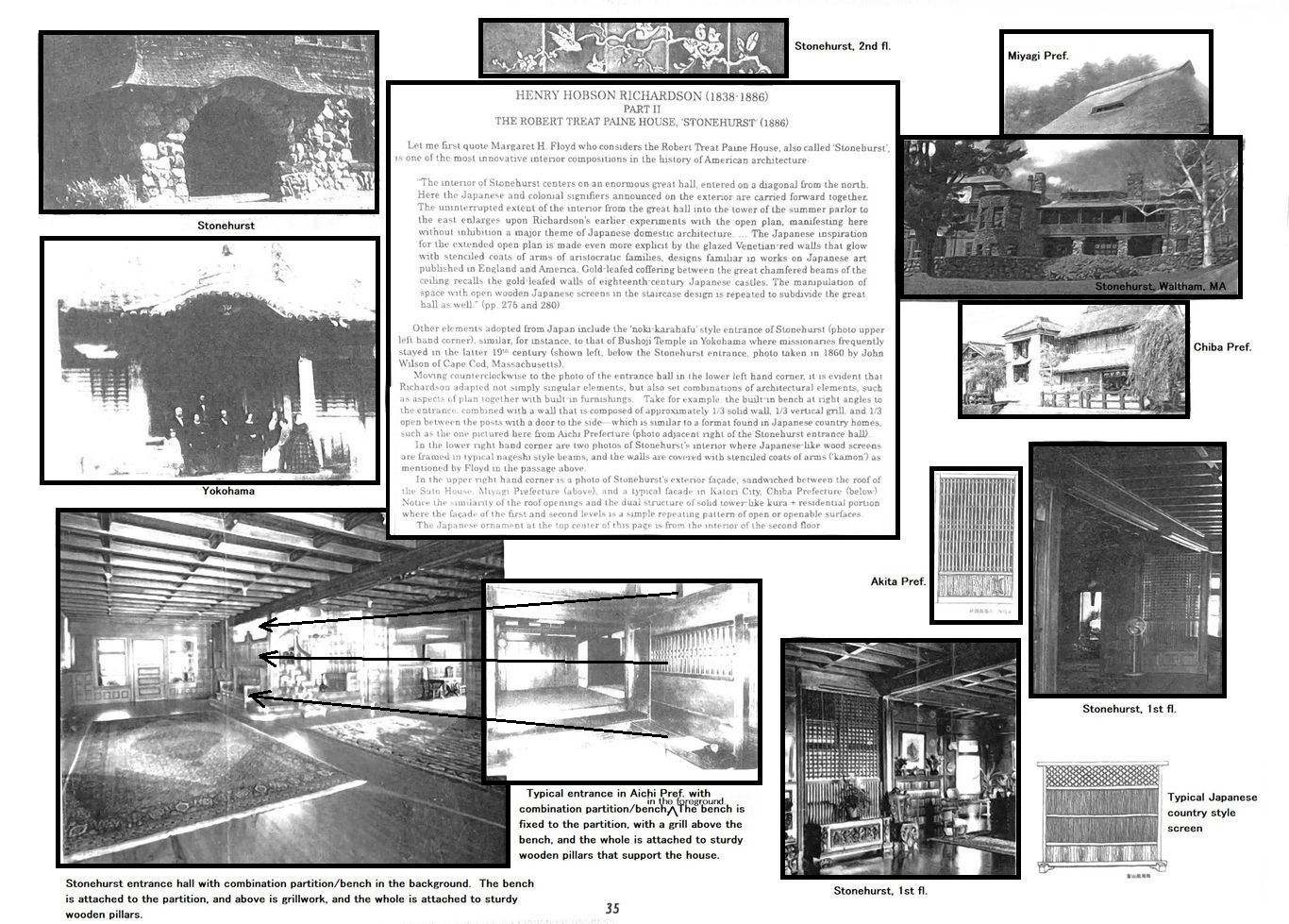

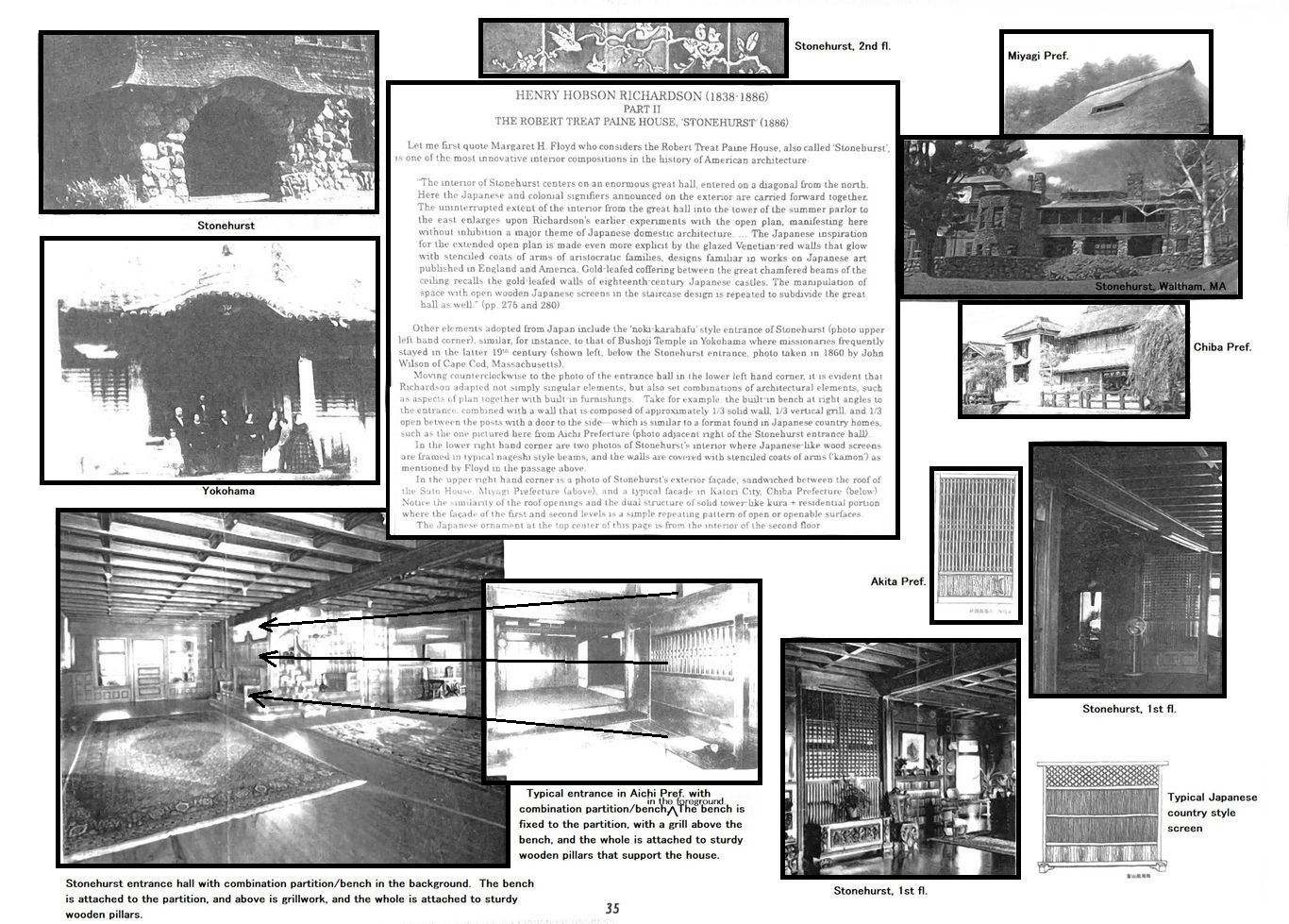

Henry Hobson Richardson, Part II

The Robert Treat Paine House, 'Stonehurst' (Waltham, MA)

Lecture handout 2015.11.5, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 35

________________________

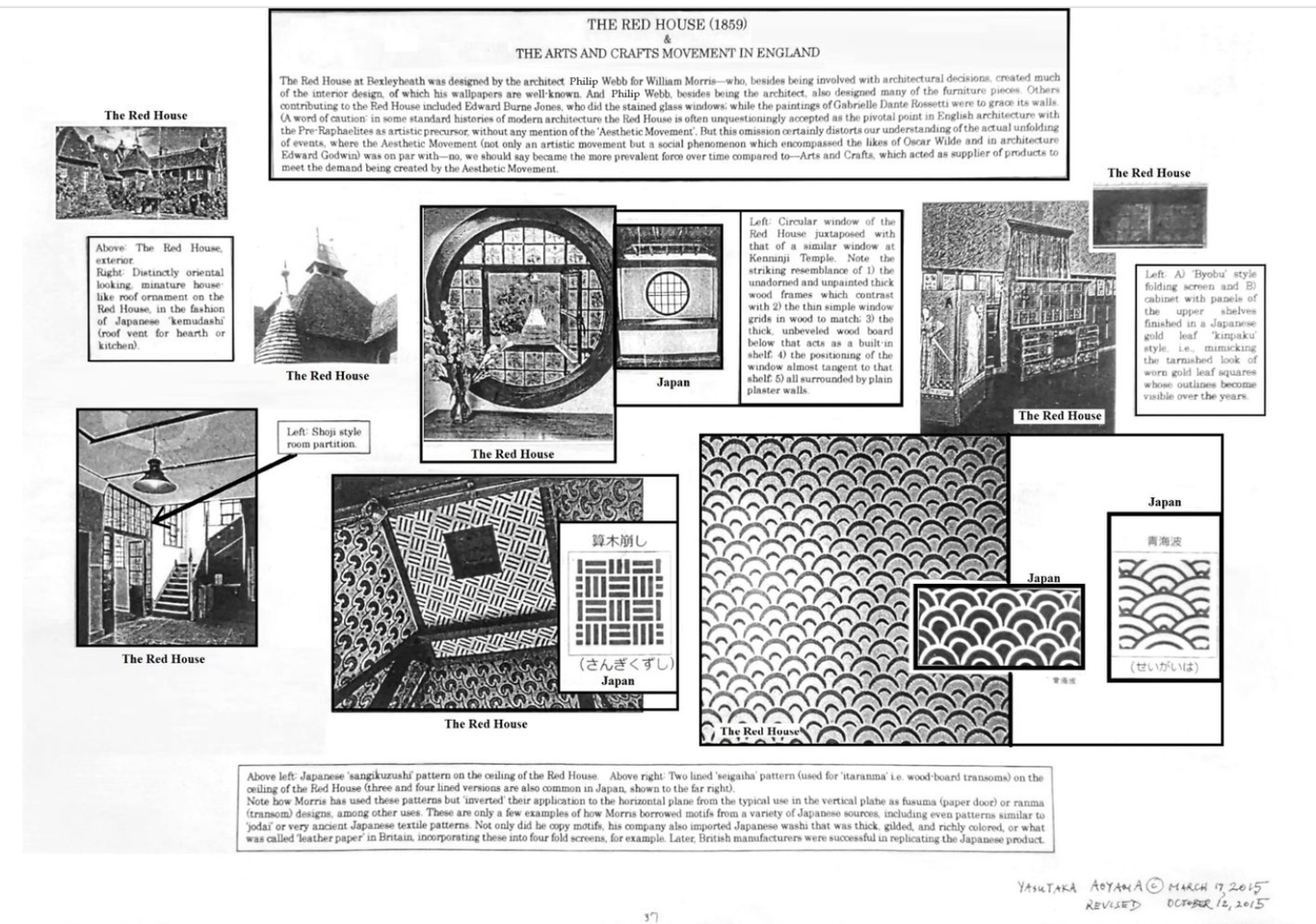

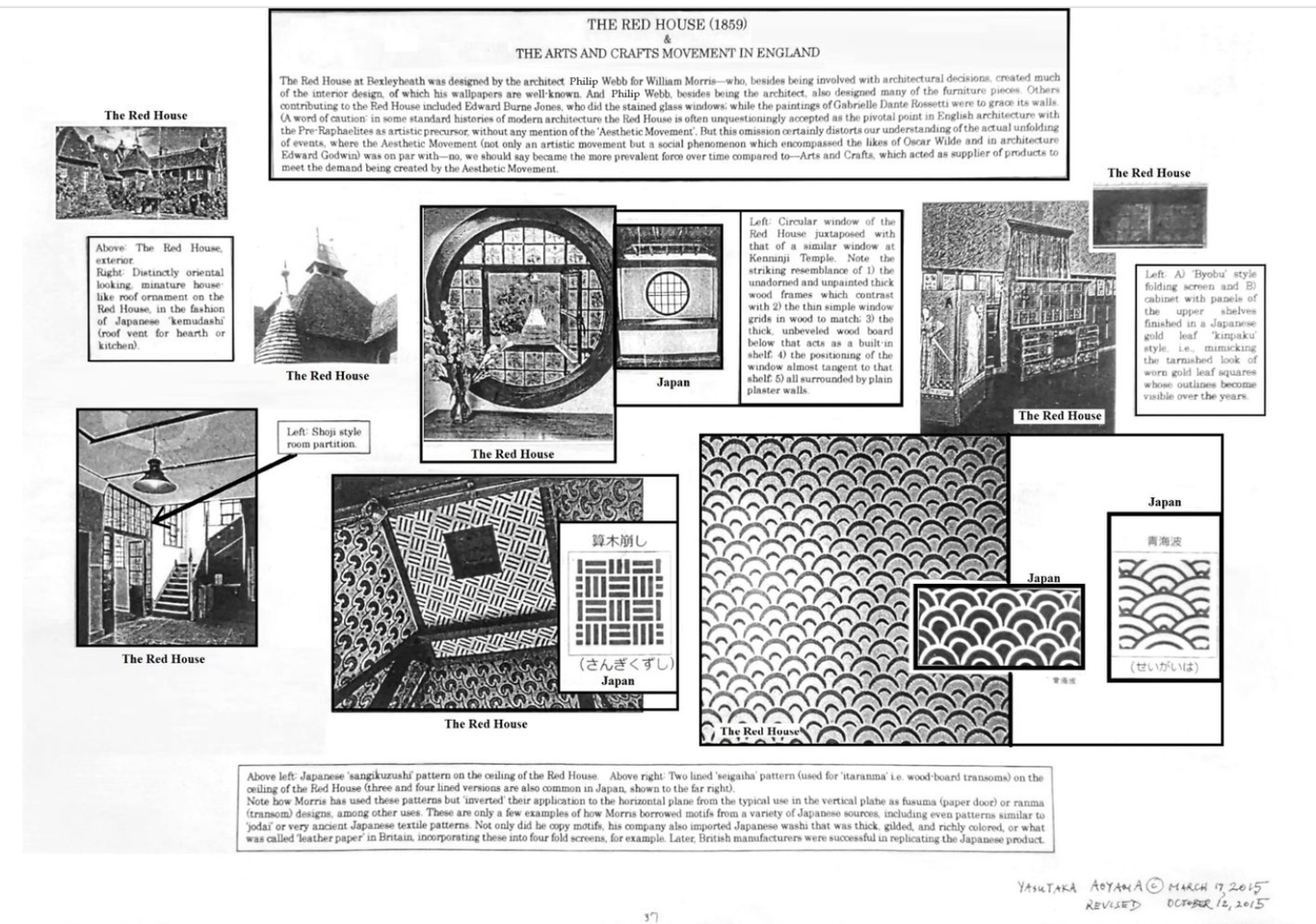

Philip Speakman Webb (1831-1915)

The Red House and the Arts and Crafts Movement in England

Lecture handout, 2015.3.17, revised 2015.10.12, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 37, with added material, 2023

Yasutaka Aoyama

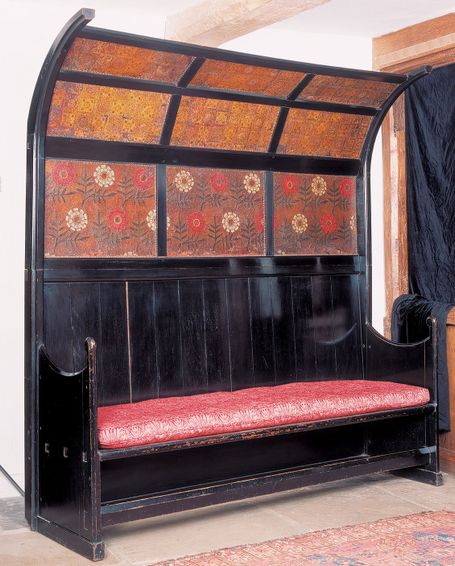

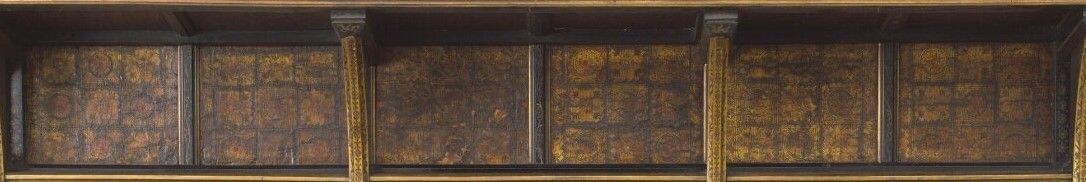

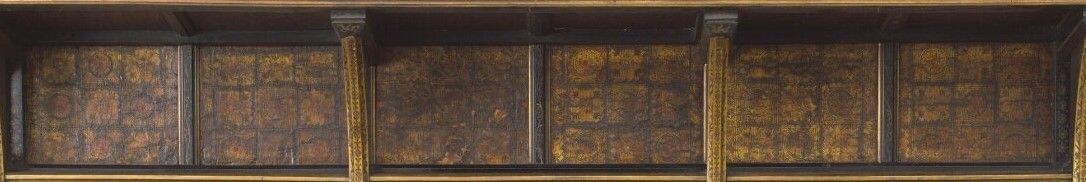

Above center is a settee designed by Philip Webb at Kelmscott Manor (but originally made for the Red House), that is remarkably similar in impression to the form and designs on 'gotenjo' (格天井) ceilings found in temples, shrines, palaces and castles in Japan, such as in Nijojo Castle, Kyoto, shown on both sides of Webb's settee.

The Arts and Crafts Movement is often discussed--strangely enough--in isolation from other contemporary artistic movements, such as the Aesthetic Movement at the time, and certainly not in relation to japonisme. Perhaps because William Morris (1834 – 96), its leading spokesman, never admitted to any Japanese influence. Yet in so many respects, the Arts and Crafts Movement--from the espousal of a general raising of the level of artistry in British craftsmanship, down to the specific textile designs Morris himself produced, show a strong affinity to the ideas and designs of Japan. A variety of Japanese artwork, artifacts, depictions, and accounts had been trickling into Britain particularly after Commodore Perry's expedition to Japan in 1853 and the Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Amity and Commerce in 1858. Such plausible influences however, are often met with disbelief, due in part to modern surveys of western civilization and art history which tend to minimize certain trends--even if they were once an incontrovertible part of everyday life. This holds especially true in the case of Japanese influence. As Elizabeth Aslin in The Aesthetic Movement: Prelude to Art Nouveau (1969, p. 79) writes:

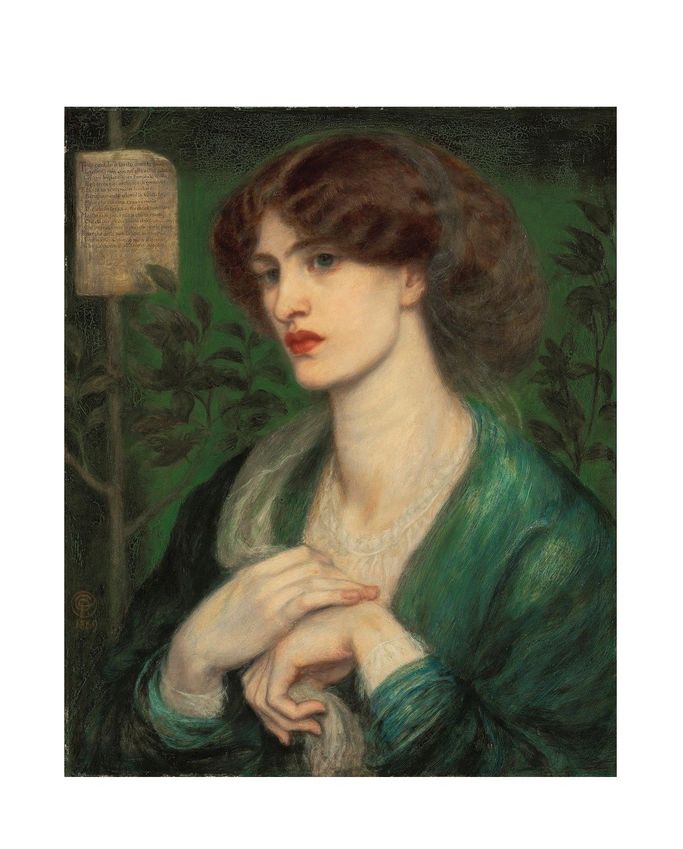

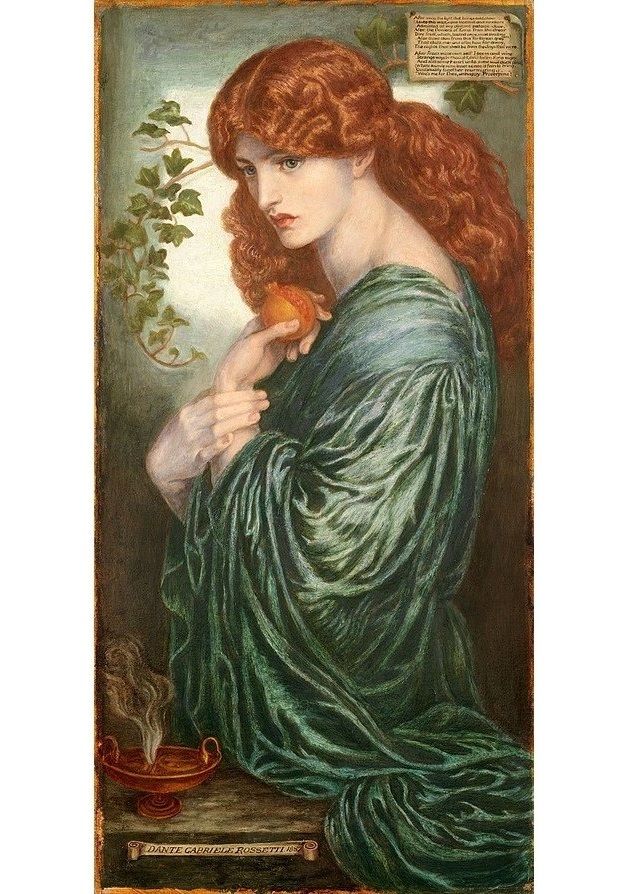

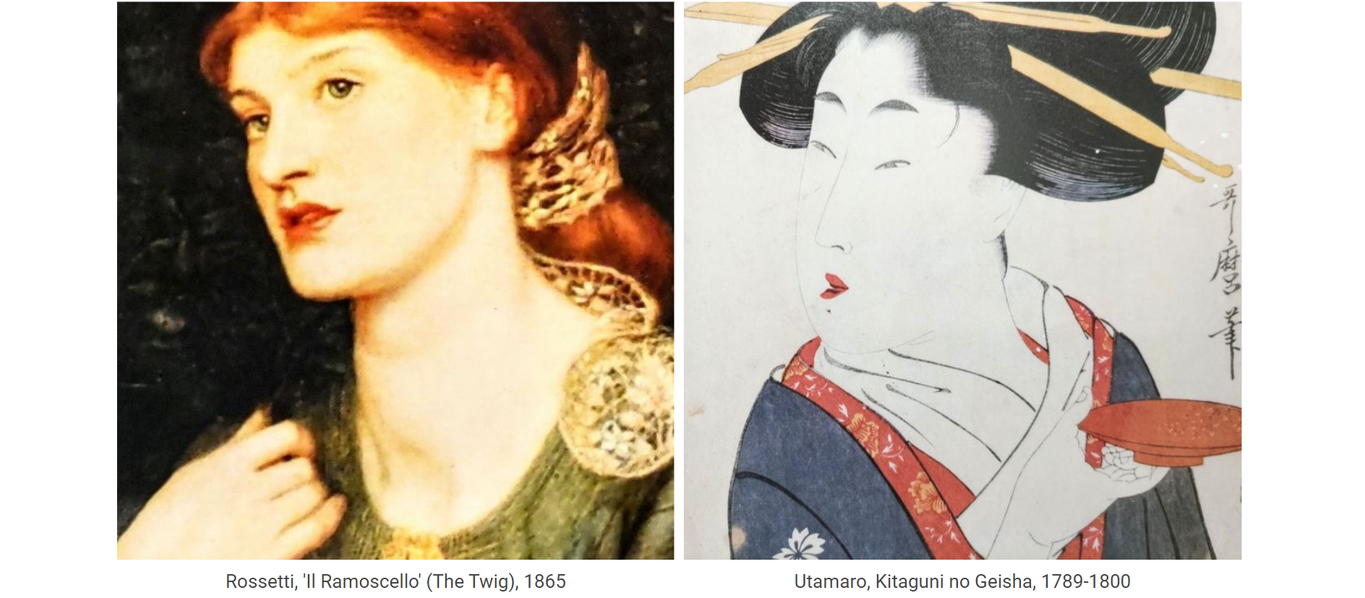

"The impact of Japan on the decorative arts in England in the second half of the nineteenth century has never been fully explained though the influence itself passed through three clear phases each of which conveniently falls into a decade. In the eighteen-sixties it was a matter for individual collectors and enthusiasts, both in England and in France, and in that period Whistler produced his earliest Japanese-inspired paintings, Rossetti designed a Japanese bookbinding and a few amateurs began to collect lacquer, porcelain, glass and prints. In the 'seventies, the fashion was in full swing amongst informed people and Japanism and the Aesthetic Movement were virtually synonymous, while the Philistines scoffed. Interior decoration and furniture design were based on what were believed to be Japanese principles, rather than on the superficial forms and ornament which were the hallmark of the 'eighties when what had been a movement became a mania. Every mantelpiece in very enlightened household bore at least one Japanese fan, parasols were used a summer firescreens, popular magazines and ball programmes were printed in asymmetrical semi-Japanese style and asymmetry of form and ornament spread to pottery, porcelain, silver and furniture."

The Japanese artistic influence upon those associated with Morris or his wider circle, such as Edward Burne-Jones, Ford Madox Brown, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and William Burges has been repeatedly documented. If William Morris himself did not admit to a general Japanese influence, those intimately associated with him did. Even Warrington Taylor, Morris’ business manager, in a letter to the architect Edward Robert Robson (1835–1917) who associated with the Pre-Raphaelites, clearly recognized Japan as a major force in shaping English art, architecture, and crafts, writing in praise of Japanese styles: "Japanese spirit of early Worcester china is good" and the "painted cabinets in Japanese style of Queen Anne time are good" and he considered English Gothic as being "Japanese" in its small, picturesque, and homely nature. (Warrington Taylor to E. R. Robson, in Mark Girouard, Sweetness and Light: The “Queen Anne” Movement, 1860– 1900. Oxford: Clarendon, 1977, p. 15.) One only has to dig a little below the surface, and around Morris, to find Japan firmly intertwined in the roots of the Arts and Crafts Movement.

The Red House below designed by Webb is a solid example of the early phase of japonisme in Britain.

Below: Close-up of cabinet detail in the upper right hand corner of the lecture handout above. Note the squarish shaped indistinct pattern, very much like 'kinpaku' or gold leaf coverings pasted in similar squares, on Japanese walls/ceilings and byobu screens, whose divisions gradually become apparent and grow sullied over time. The main part of the cabinet, though not show here, is also very much in the style of Japanese box-like lacquer cabinets, adopted for Western style use, in vogue from the 17th century onward among elites in Holland and Germany.

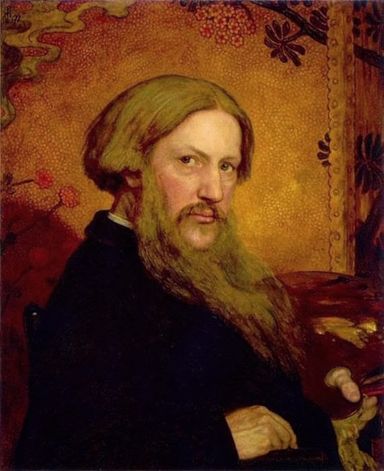

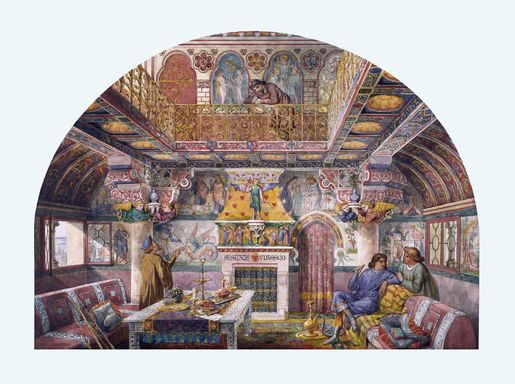

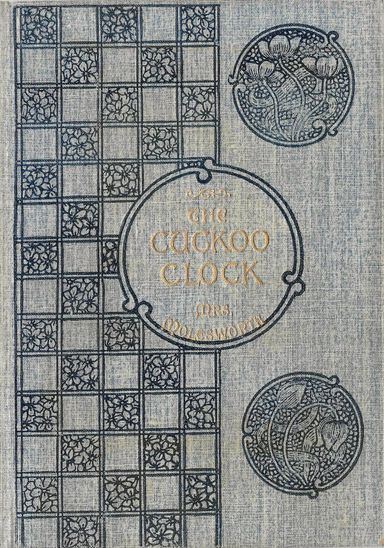

Japonisme added color, verve, refinement, and diversity to English arts and crafts. Below, from left to right: Ford Madox Brown chooses to paint himself in front of a Japanese, or Japanesque screen (1877). Using Gothic motifs, William Burges has all but re-created the Nikko Shrine of the Tokugawa Shogun in his 'Summer Smoking Room' design for Cardiff Castle (1870). Recall that Burges, upon seeing the Japanese Court at the International Exhibition of 1862, declared "if the visitor wishes to the see the Middle Ages, he must visit the Japanese Court" (Ashmolean Museum, www.ashmolean.org/article/east-meets-west-in-the-victorian-colour-revolution). Walter Crane, well researched for his Japanese design proclivities, here creates a book binding (1901) that without the English words might easily be mistaken by anyone familiar with traditional Japanese patterns as being from that country. Edward Byrne-Jones, inspired by Japan to advance English aesthetics based on home grown sources, merges Japanese lacquer case and vegetal design into a discoidal object in 'Days of Creation--The Third Day' (1870-1876).

Though we will not delve deeply here, ceramic dishes by William de Morgan, while many are clearly influenced by Persian and Turkish ceramics, an equal number of other pieces are likely to have been influenced by Japanese Kutani ware, such as his blue, green and yellow colored plates with dragon or beast motifs (corresponding to 'ryu' and 'shishi' / 'komainu') or his all red on white ceramics reminiscent of red Kutani plates (some with fish motifs corresponding to swimming carp and jumping 'tai' sea breams), while his richly multicolored peacock plates (one shown below) may be considered part of the same stream coming from Japan that gave birth to Whistler's Japanesque peacock room. Besides being a common traditional motif in 'kacho-zu' (bird combined with flower designs), peacocks have been drawn and sculpted in painstaking detail for approximately a millenium as the vehicle of the Buddhist deity, 'Kujaku Myo-o'. Regarding furniture, Charles Robert Ashbee's designs at times shows similarities to those typical of Tohoku (northern) Japan, box-like with oversized drop-handle pulls against large back plates and elaborate escutcheons; while there are other pieces by him, more light and airy, that seem influenced by Edward Godwin's 'Anglo-Japanese' style or examples of thin, straight-legged laquered Japanese table and desks. And finally, some of William Morris's woodblocks at Kelmscott Manor for making prints on fabric, indicating the analogous nature of his approach to that of Japanese woodblock printmaking; and as in Japanese woodblock prints, it is said that sometimes a dozen or so blocks were used to complete one design.

________________________

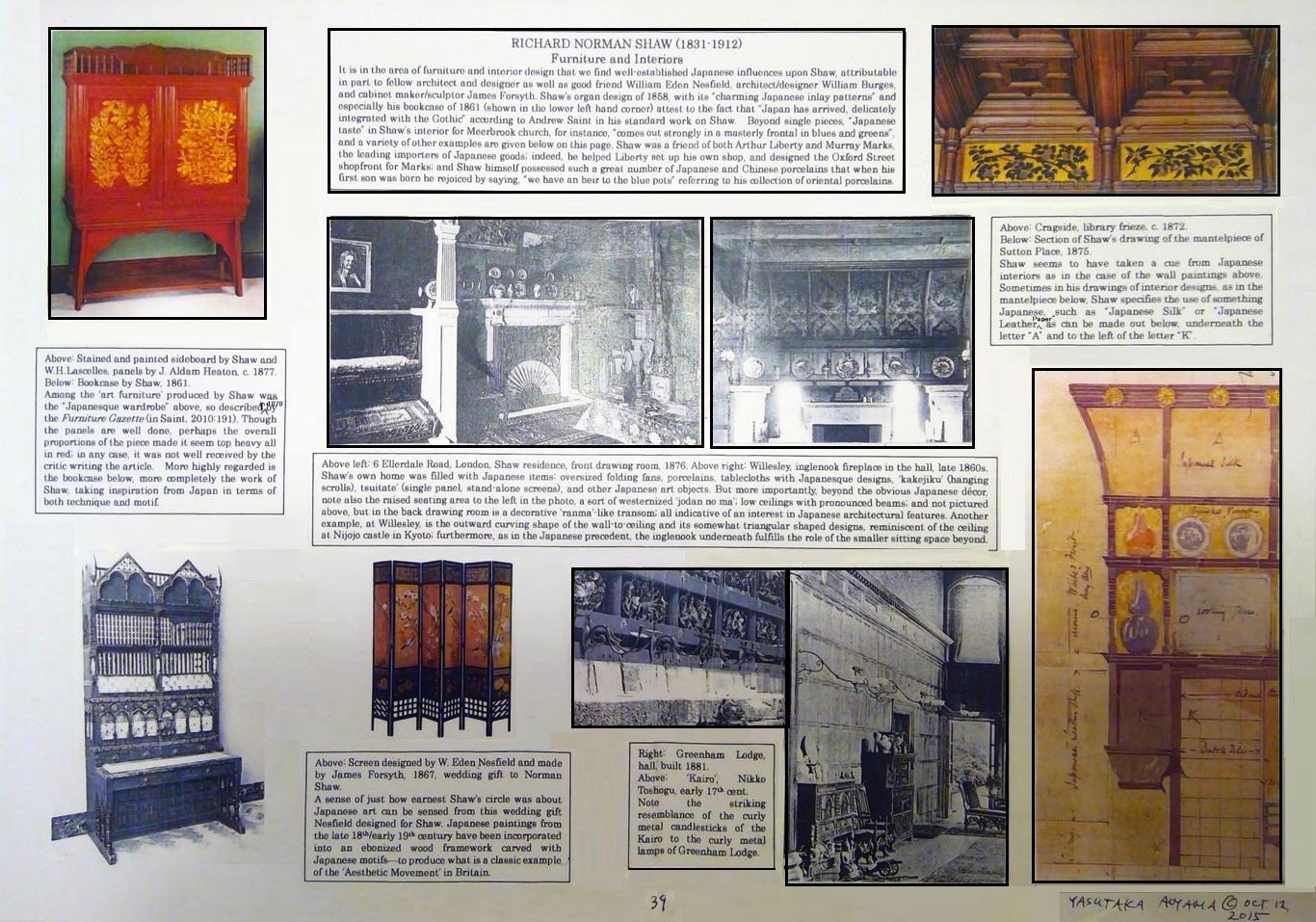

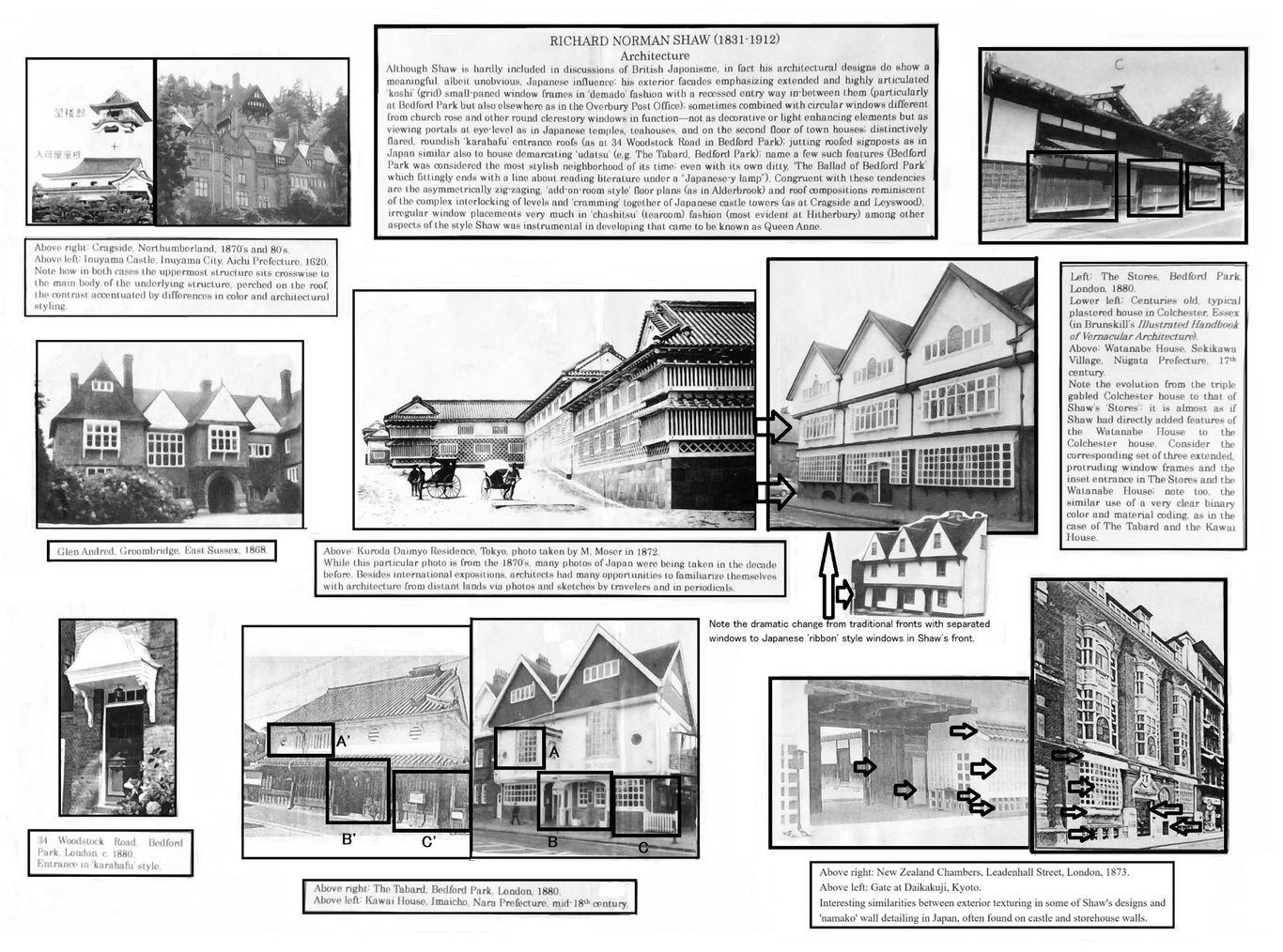

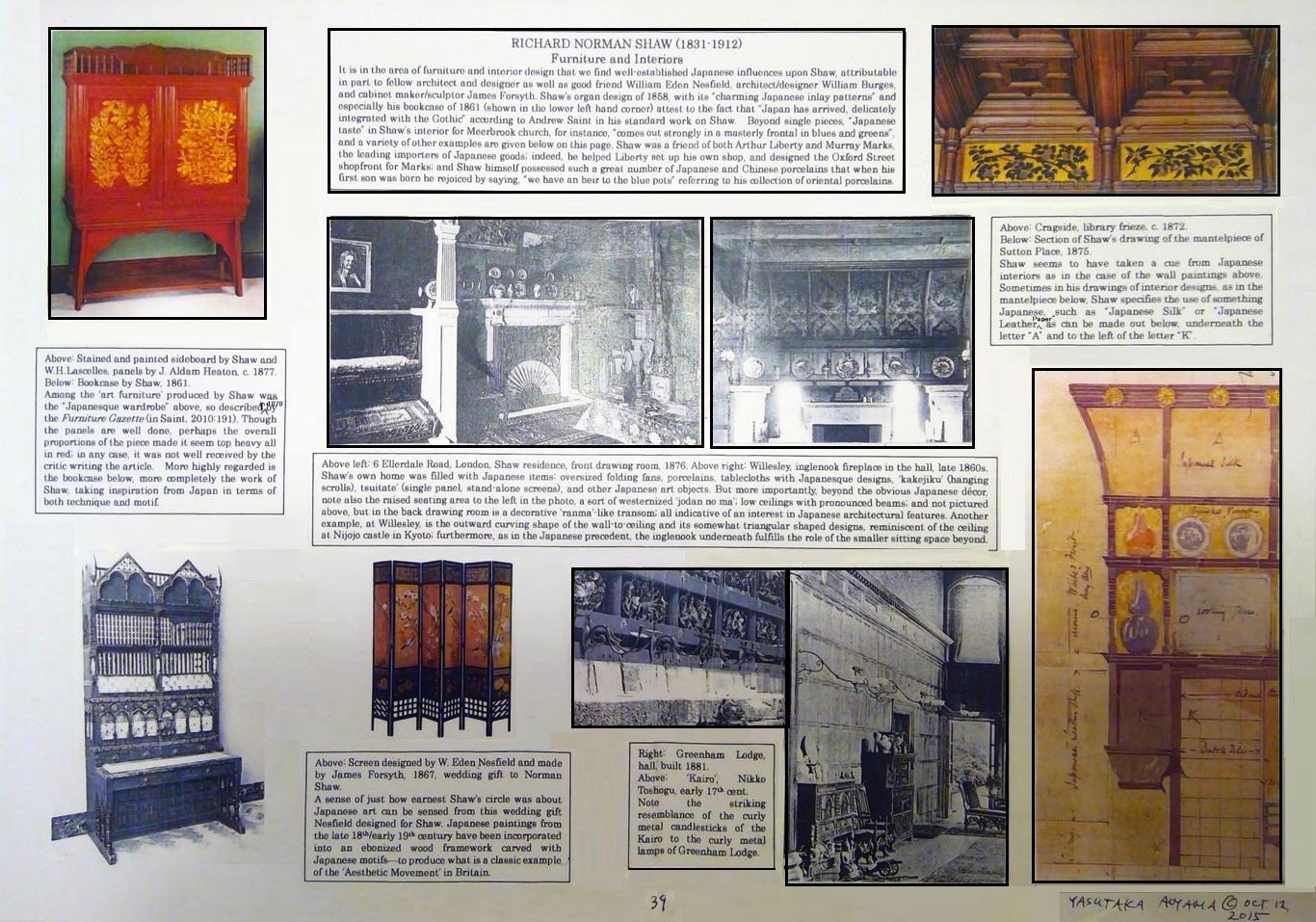

Norman Richard Shaw (1831-1912)

A Confluence and Congruence of Japanese and English Taste

Furniture and Interiors

Lecture handout 2015.10.12, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 39

Yasutaka Aoyama

Regarding Cragside's interior design, Andrew Saint writes of the subtlety with which Shaw incorporates Japanese taste, before becoming obviously oriental looking in the years to come: "In the movable furniture weight and nimbleness respond to one another in fresh guise, llike the second subject in a symphony. Mass of table and density of carpet form a backdrop for a superb set of ebonized chairs made by Gillows, presumably from Shaw's own pencil though touched by the impact of the lighter early pieces made by the Morris firm. They stand for a moment of equilibrium in English furniture design, before the Japanese taste dissolves into the spindliness of aestheticism. Their neatly turned legs and cane seats are spiced up with discreetly exotic small back panels in gilt leather, parading pomegranates and picking up the tones of the frieze." (Richard Norman Shaw, revised edition, Yale Univ. Press, 2010, p. 84)

Regarding Shaw's designs for Meerbrook church in Staffordshire, Saint comments, after describing various decorative details and fittings of the chancel: "The Japanese taste, well subordinated in these fittings, comes out strongly in a masterly frontal in blues and greens, the first recorded piece to be worked by the ladies of the future Leek Embroidery Society." (2010, p. 303)

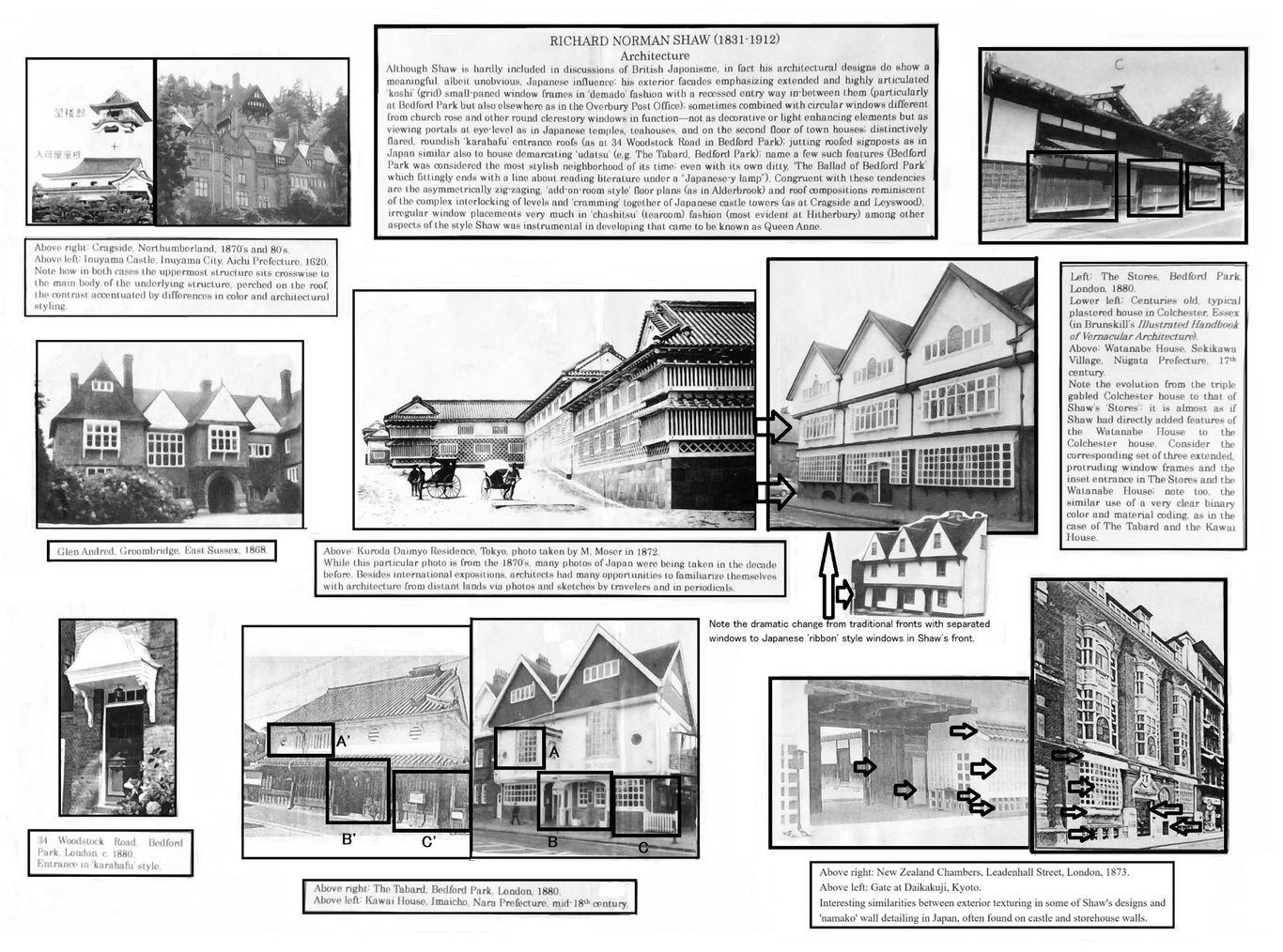

Richard Norman Shaw

A Confluence and Congruence of Japanese and English Taste

Architecture and Exteriors

Lecture handout 2015.10.12, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 38

Yasutaka Aoyama

Text below added 2023.7.19

While the Japanese influence upon Shaw's interiors is straightforward, and of a decorative aspect, the influence of Japanese architecture upon his exteriors is likely to be met with greater skepticism. Yet the fact that the creators of the Queen Anne style, led by Norman Shaw and Edward Godwin, had a strong interest in Japanese art is undisputable, and and at times reveals itself in earlier proposals for houses, which are then modified to accustomed tastes (that might even be said of J.J. Stevenson, when one looks at his design for T.H. Green's house in Oxford, in its subtle asymmetric rendering of the exterior coloring).

Consider the basic concept and imagery of Bedford Park, as visualized in Shaw's sketches of the place, such as his 'St. Michael and All Angels' (1879). It has an unmistakable ukiyo-e feel to it, for one who is familiar with Japanese prints. The single, slender, dominating tree, which extends to the top of the picture, is somewhat reminiscent of the compositional technique that impressionists and post-impressionists are known to have adopted from Japanese prints. Colored expansively in consistent tones of light green and orange, with touches of yellow and pale violet in clear outlines, with certain areas left unpainted, and with hardly any shadowing (as if high noon were a device to minimize shadowing), it calls to mind mid-18th century ukiyo-e prints such as those of Suzuki Harunobu, sharing the same quiet softness of his images, despite the obvious difference of setting. The small child holding a Japanese style parasol in Shaw's watercolor---has she been placed there almost as if a reminder---to evoke the imagery of a far away land transposed to comfortable England?

Much the same can be said of other better known images of Bedford Park, such as the cherry blossom or the very cherry blossom-like apple blossom filtered lithograph 'Bedford Park' (1882) by Manfred Trautschold.

There is no insistence that each and every correspondence below be considered one of cause and effect. Rather, they are pointed out to show a growing congruence of Shaw's designs with Japanese architectural forms in many respects, and not substantially in another direction. And that as a whole such a convergence, whether conscious or unconscious, makes sense given the exposure to images of Japan in published photos or pictures as those in the Illustrated London News (see Japan and the Illustrated London News: Complete record of Reported Events 1853 - 1899, publ. 2006); and in ukiyo-e prints, inevitably filled with architectural forms, which were also to be found on porcelains, lacquerware, fans and the like, the sort of things Shaw collected and enjoyed. In Harunobu's ukiyo-e, just to take one example of devices reminiscent of what Shaw would come to employ with frequency, large round windows near gridded shoji panels (light passing and thus like translucent windows) are a favorite backdrop.

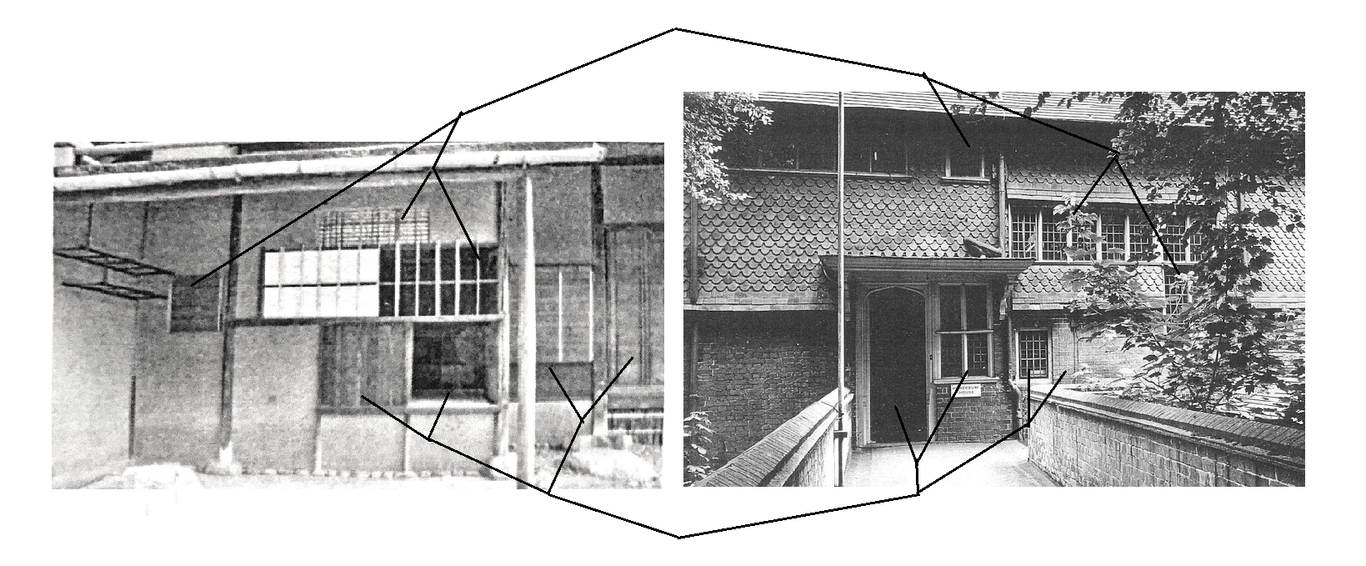

Below: From the author's scrapbook, the Shaw designed Hitherbury House (1882), Guildford, England on the right, next to an old Japanese teahouse 'chashitsu' on the left. Perhaps the most outstanding example of Shaw's incorporation of Japanese style architectural asymmetry, juxtaposition of elements of different scale, and textural variation for a facade.

For more on Shaw, see Architectural Japonisme II, 'William Eden Nesfield: An Unassuming Japonisme'.

________________________

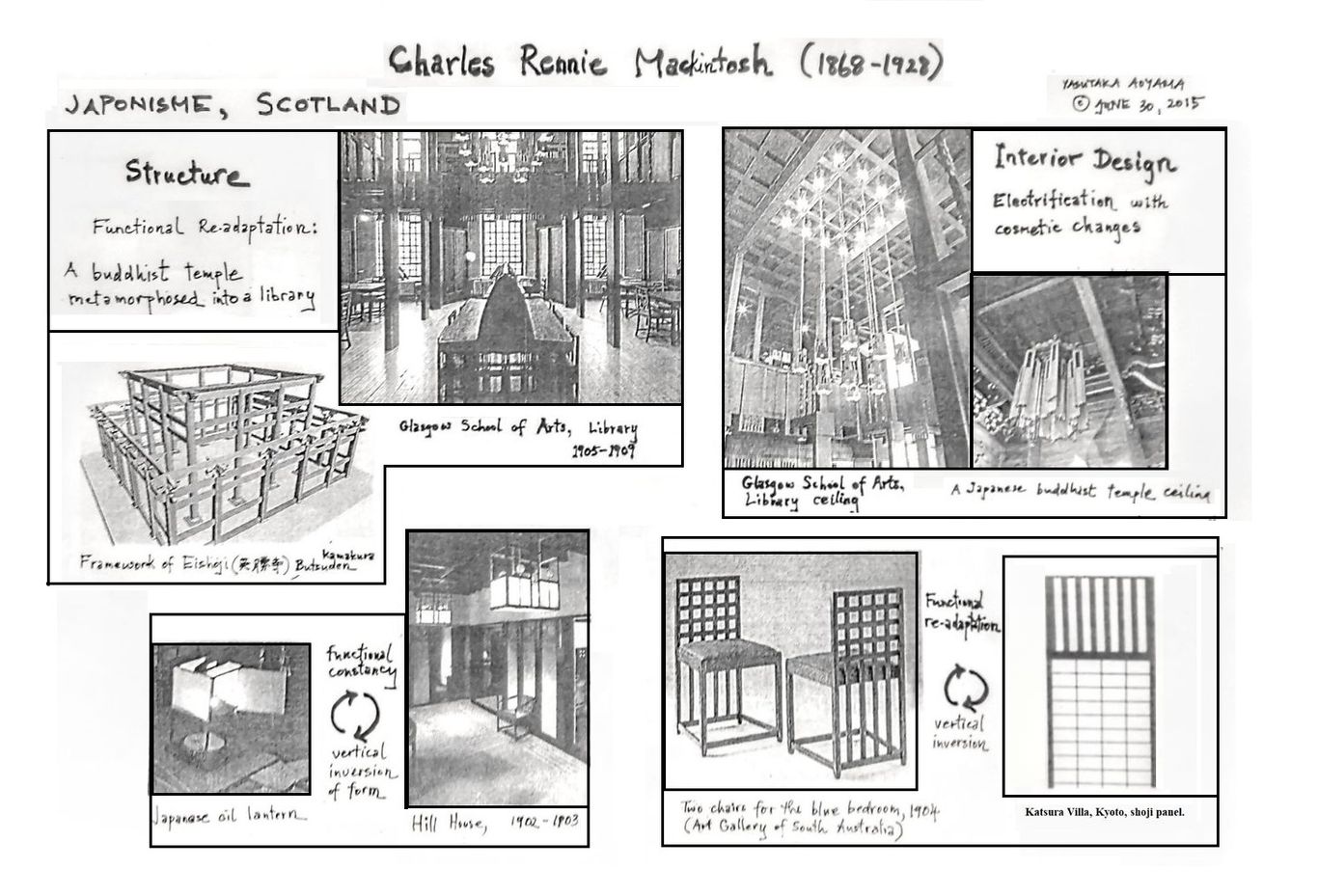

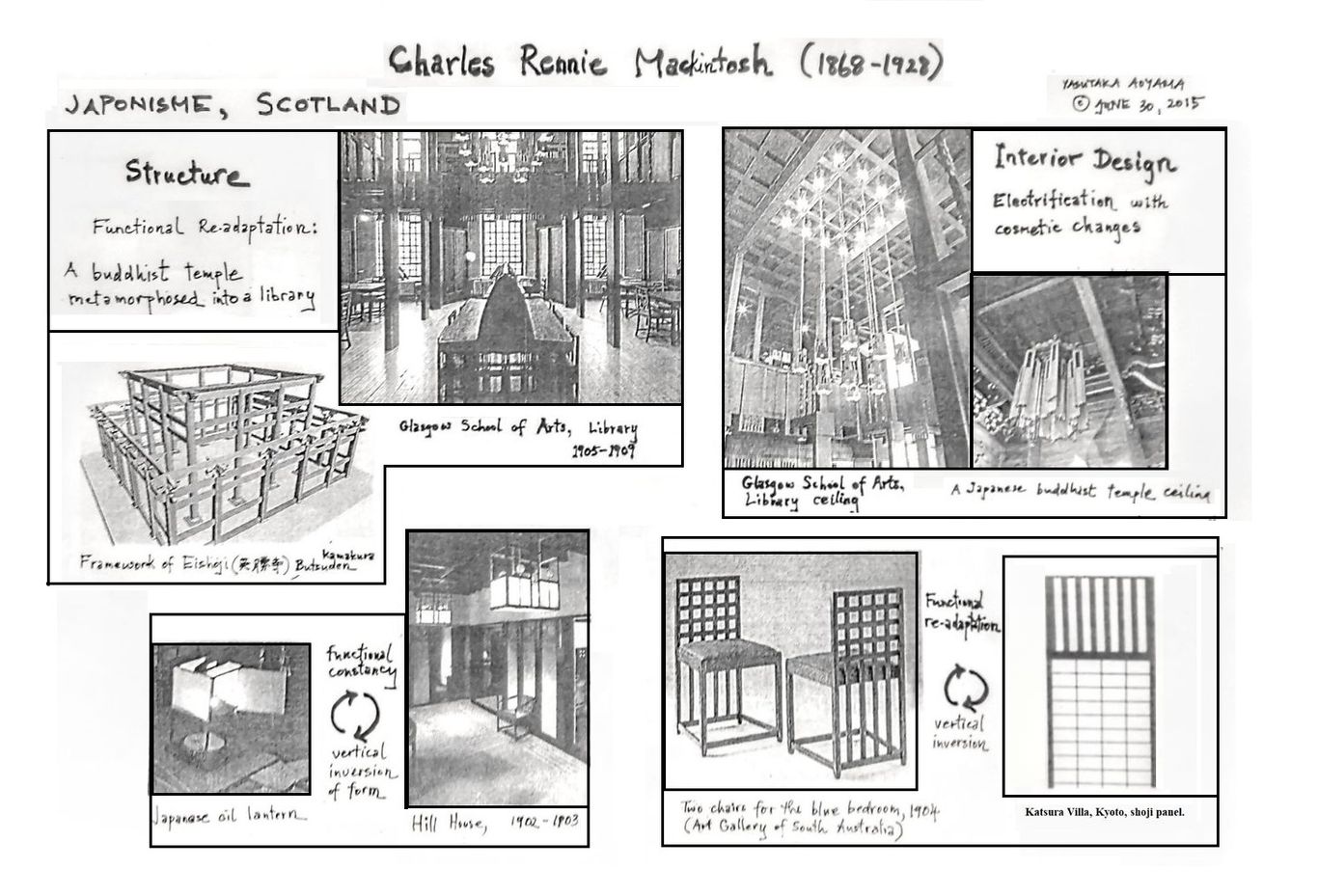

Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928)

Part I: Functional Readaptations of Japanese Designs

(with Observations on an Interior by Sir William Reynolds-Stephens)

Lecture handout, scrapbook form 2015.6.30, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 40, note on Reynolds-Stephens added 2024.9.17

Yasutaka Aoyama

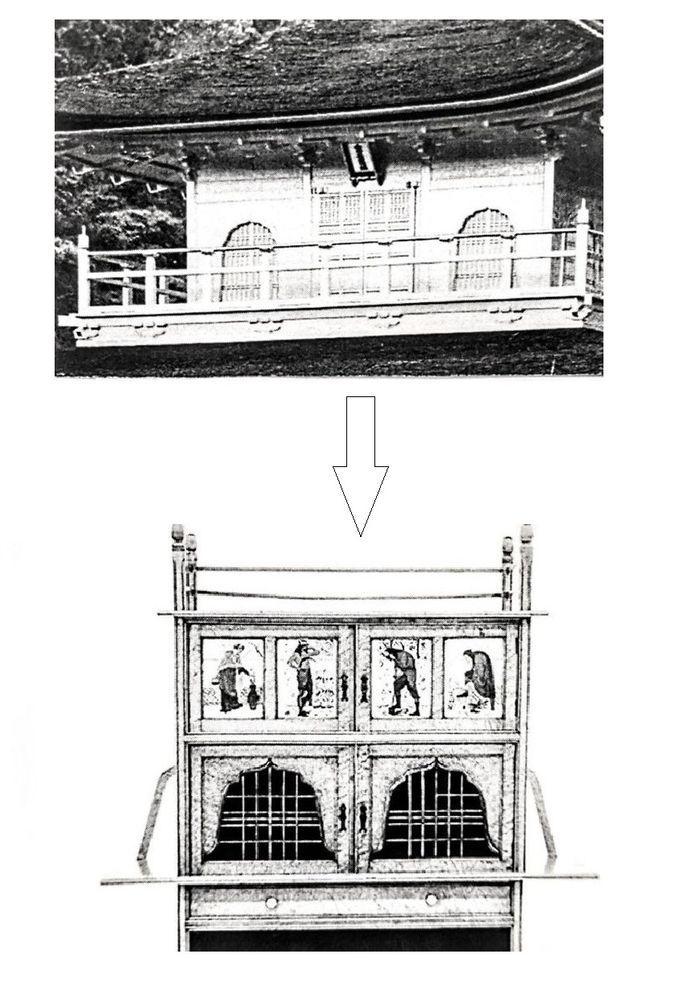

"To those with eyes to see, however, and especially to Mackintosh, the Japanese house presented a new challenge. Could the delightful freedom and spaciousness of the open plan be translated into Western terms; could its remarkable flexibility and exciting aesthetic potentialities be exploited under the climatic conditions prevailing here? These questions Mackintosh attempted to answer in his own way by the use of openwork screens, balconies, and square post and lintel construction. The influence of Japan is evident throughout his work, especially in the Cranston Tea-Rooms, and in the library at the Glasgow School of Art--even the boldly cantilevered galleries of Queen's Cross Church have at least one counterpart in the Far East, the balcony of an old inn at Mishima, illustrated by Morse."

Thomas Howarth, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, p. 225.

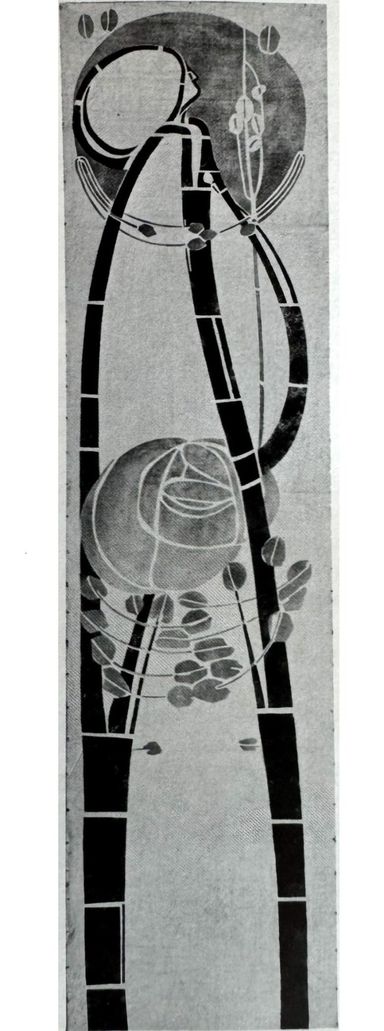

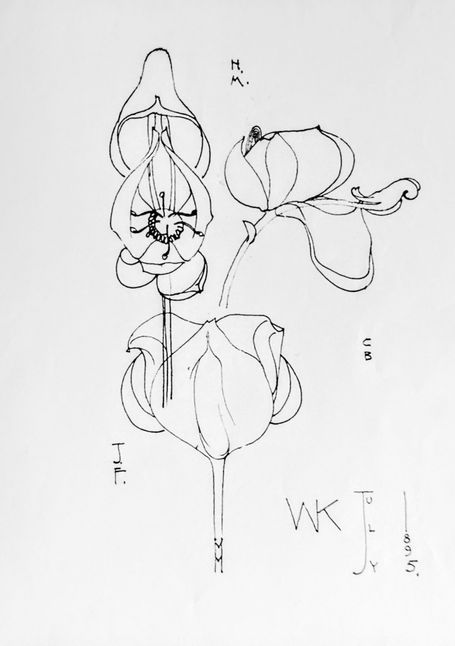

Mackintosh's first major biographer, Thomas Howarth, pointed out early on in his 1952 award-winning book, Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Modern Movement, the importance of Japan as an artistic influence on Mackintosh (see also Andrew MacMillan, 'Charles Rennie Mackintosh: A Mainstream Forerunner' Architectural Association Quarterly, vol. 12 no.3, 1980). There are many aspects of Mackintosh's Hill House, as well as his other creations such as the Willow Tea Rooms and his 78 Derngate house, that reveal an eclectic array of Japanese motifs. Those influences range from the kimono (e.g. his well-known 'kimono cabinet') and ikebana flower arrangement, to Buddhist temple design and ornament. Even his watercolor botanical sketches are reminiscent of sumi-ink painting, and are at times signed in a vertical, oriental fashion, with the words framed (boxed in) as in Japanese prints (e.g. his sketch 'Japonica'). That Mackintosh had an interest in Japanese art from his early days can be gleaned in a circa 1890 photo of Mackintosh's studio bedroom at Dennistoun, Glasgow, where an unidentified ukiyo-e print can be made out above the mantlepiece, though the Japanese lettering is indiscernible. Glasgow's relationship with Japan was closer than most might think in those years, thanks to the shipyards at the River Clyde where there was much contact with those related to shipbuilding, such as Japanese navy engineers.

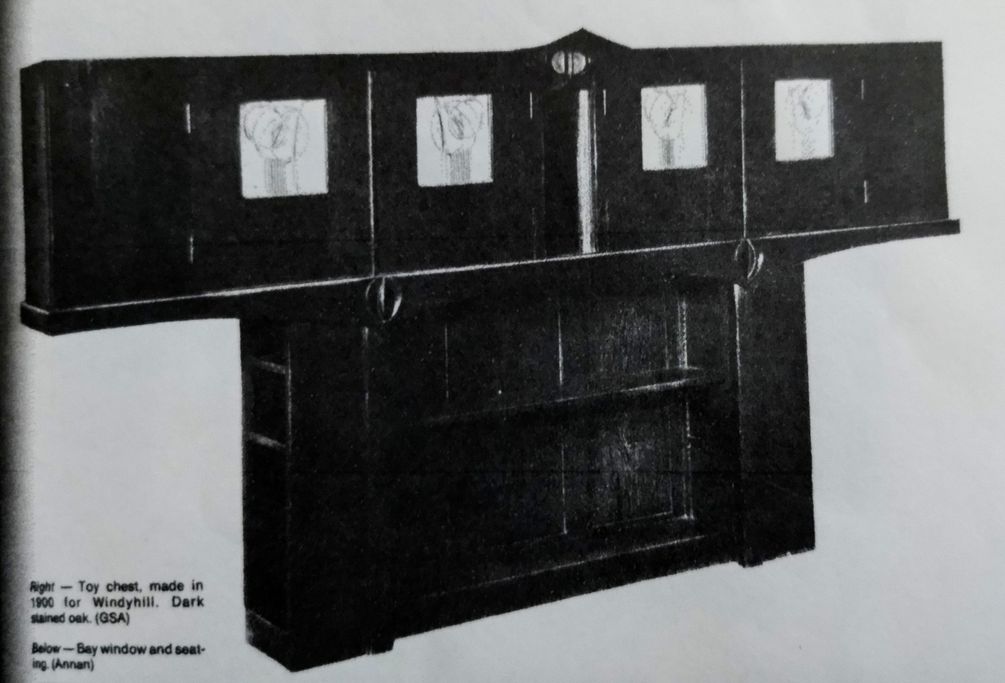

Below are some examples of Mackintosh's 'functional re-adaptations' of Japanese, especially Buddhist, architecture and ornament. A temple for instance becomes a library or a shoji window the back rest of a chair, for instance.

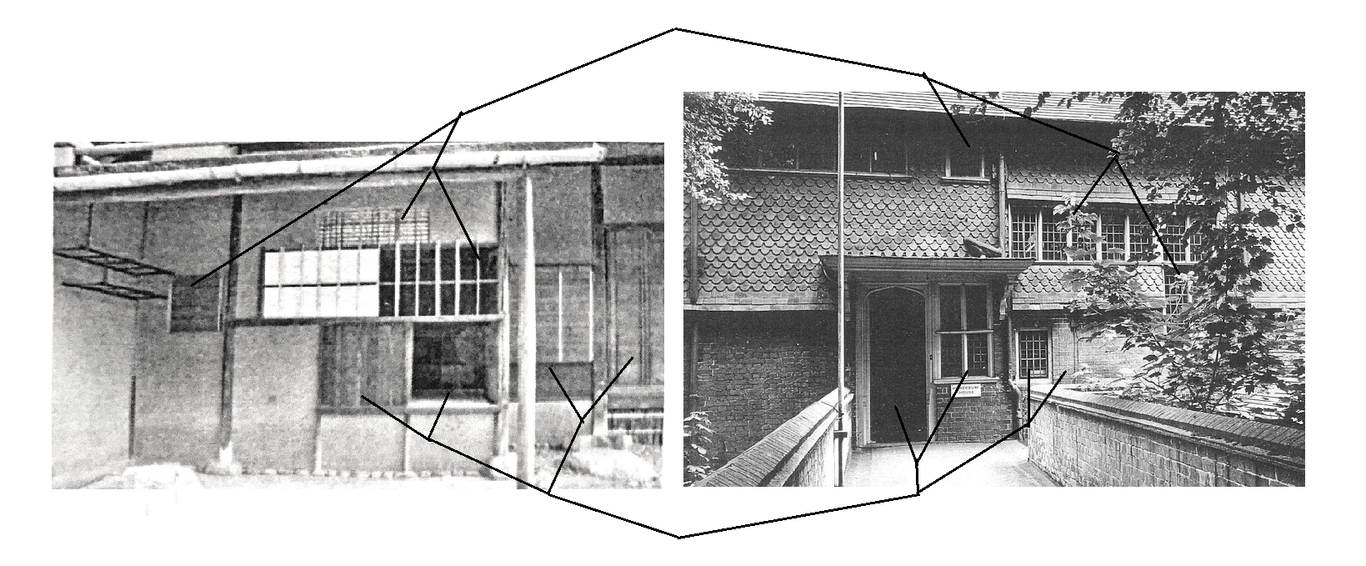

Below left: the Willow Tea Rooms, first two floors. Right: typical Japanese merchant house of the Edo period, with the 2nd floor walls in white with the quintessentially Japanese grilled window and first floor in dark wood, also with continuous windows with the lower half cut out towards the end.

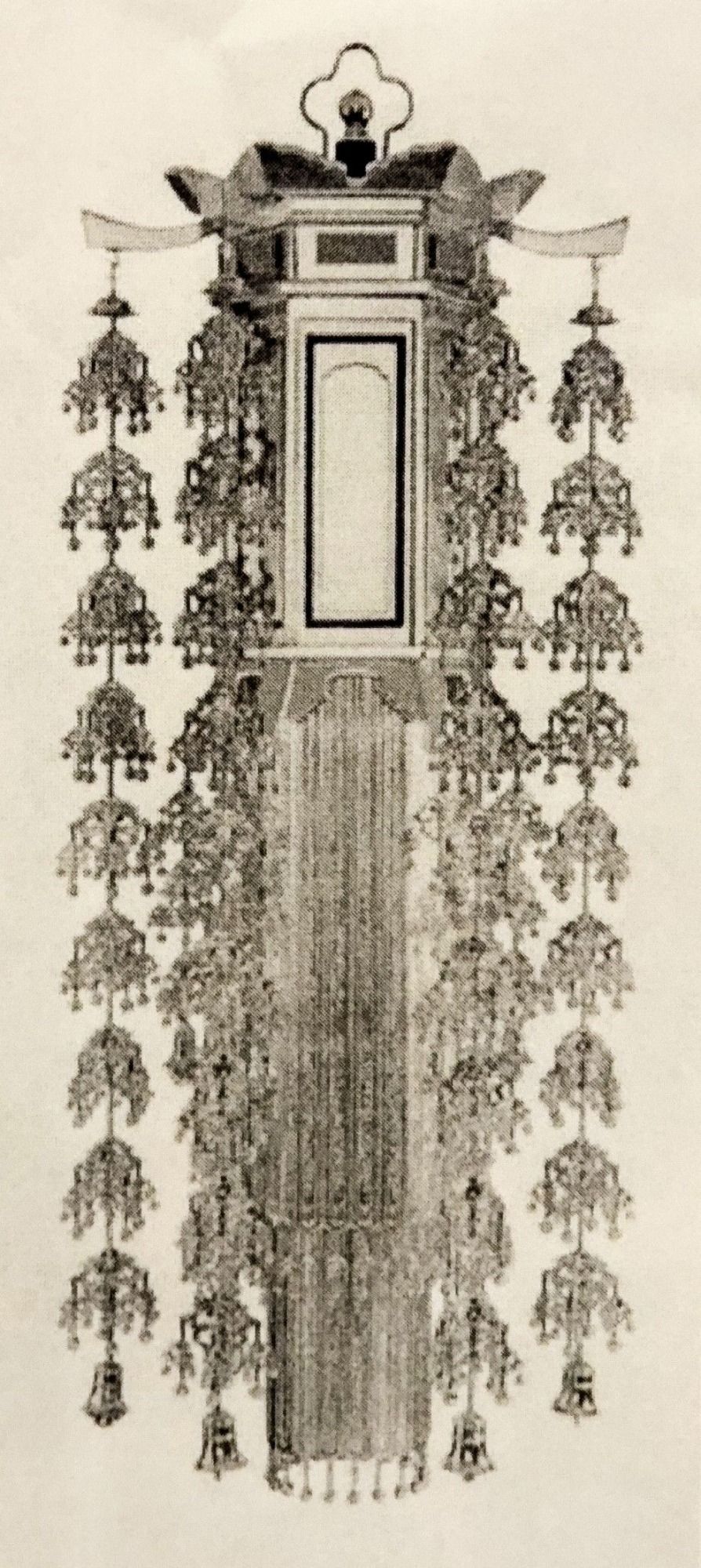

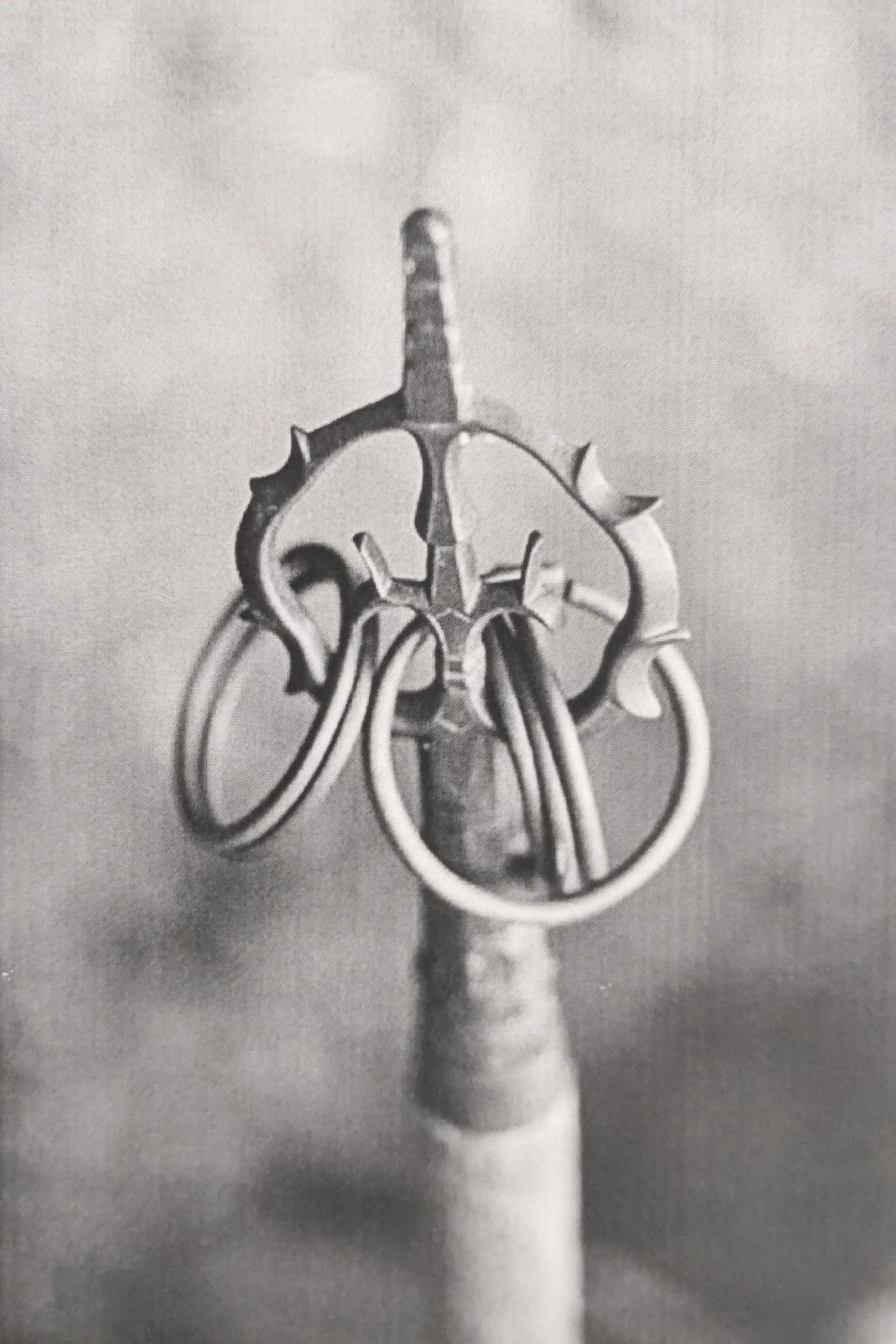

Below: Comparisons of various aspects of Mackintosh's interiors and exterior decor to the left, vis-a-vis elements of Japanese Buddhist temples and other buddhist paraphernalia to the right. Note the prominent use of black lacquer furnishings and hanging golden ceiling ornaments, and white silk panels or white plaster walls, abstracted in Mackintosh's 78 Derngate, Northhampton house, but still recognizable. These are but a few examples; not shown for instance, is a comparison of the large metal, somewhat bean-shaped ornaments that hang from Jodoshinshu sect temples of which an almost exact duplicate existed in Mackintosh's Willow Tea Rooms.

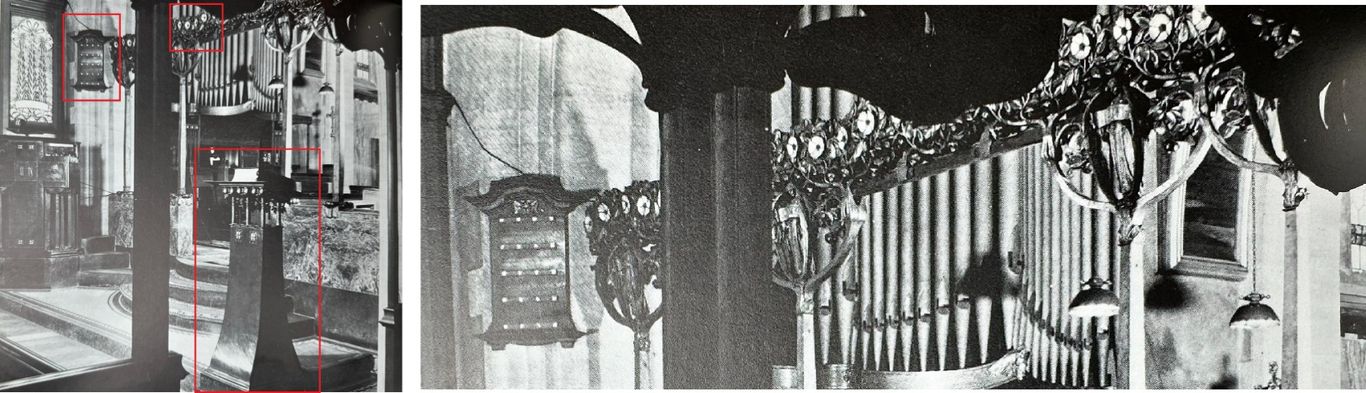

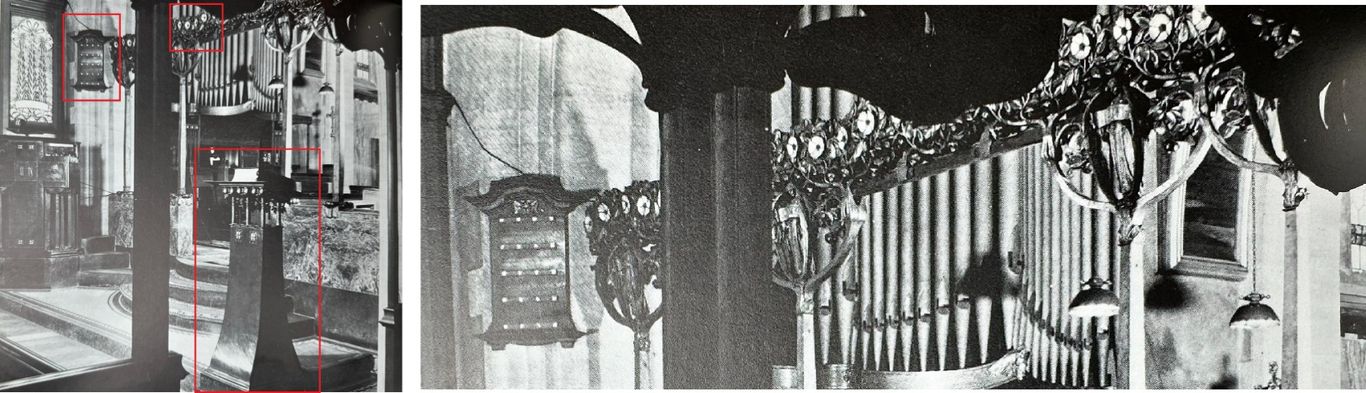

We might note as an aside that the interest in Japanese religious architecture was not limited to Mackintosh. Echoes of sacred Japanese architectural elements are found early on in the American Stick Style, discussed earlier, as well as elsewhere in Britain in Mackintosh's time. A good example is William Reynolds-Stephens' (1862-1942) design for the interior of St. Mary the Virgin, Great Warley, Essex (1904), shown below, which was completed just before the building of Mackintosh's Glasgow School of Arts Library (1905-1909). The elements blocked in red reflect various aspects of Buddhist temple or Shinto shrine structures and ornament.

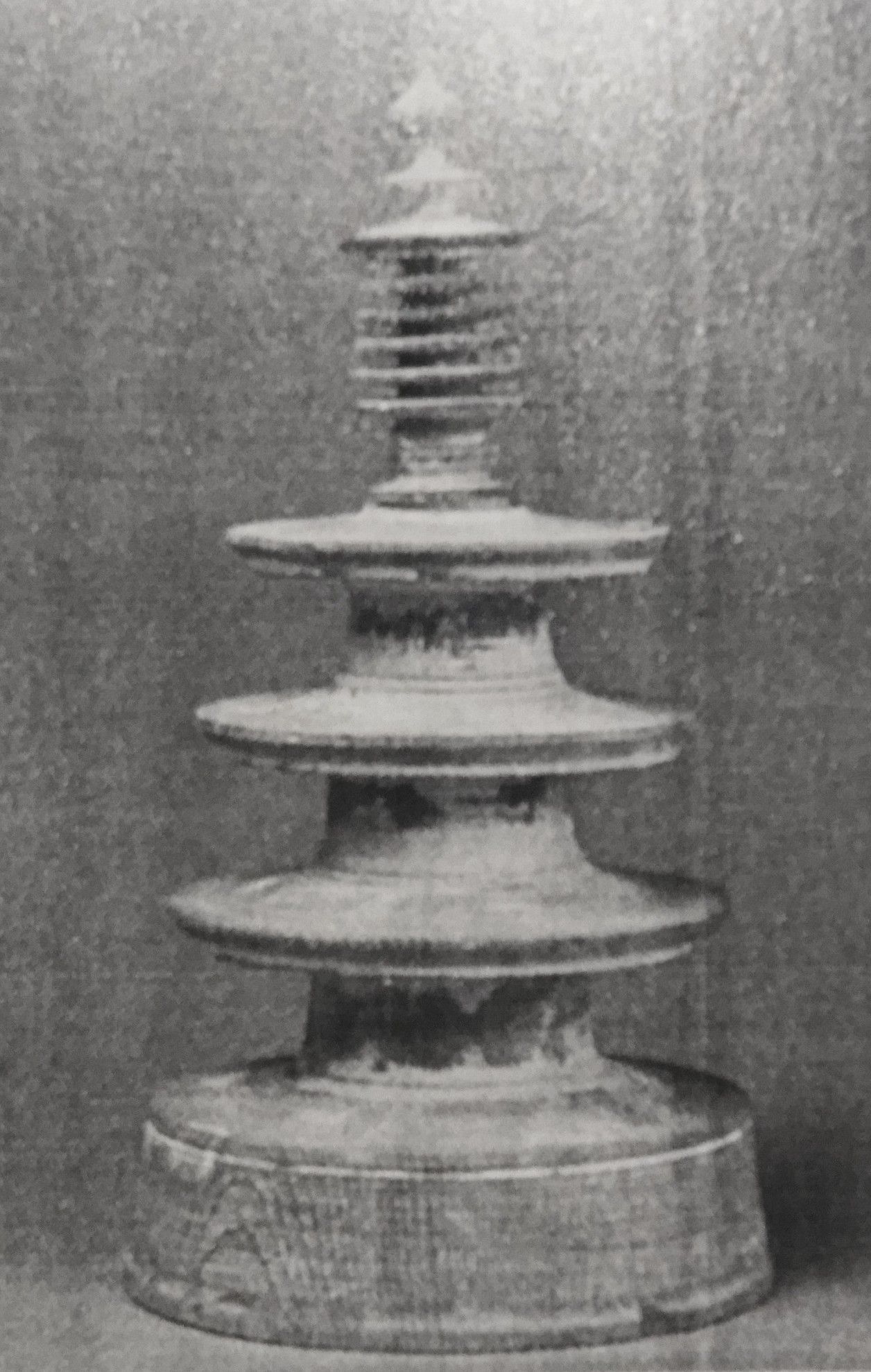

In the foreground of the picture to the left is a minature tower-like structure, which looks as if made of metal, whose form is much like that of a temple or shrine 'toro' (stone or wood lantern). To the right is a close up of the upper part of the photograph (from R. Schmutzler, Art Nouveau, 1977). In it is a hanging, roofed, plaque-like object much like a 'zushi' (minature, portable reliquary) in form, and to the right of it running horizontally is a metal ornament with a floral design, reminiscent of temple or shrine eave decorations.

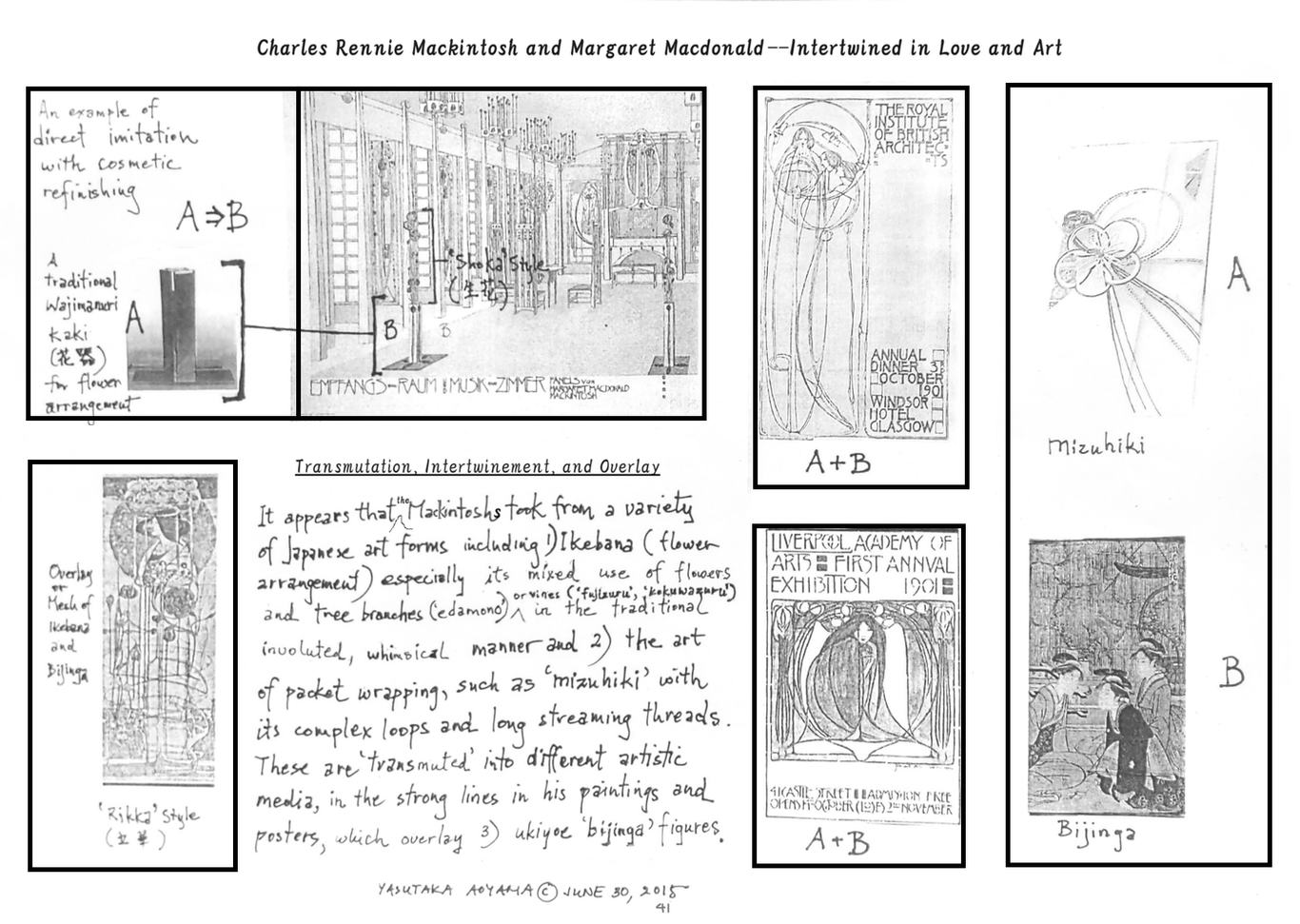

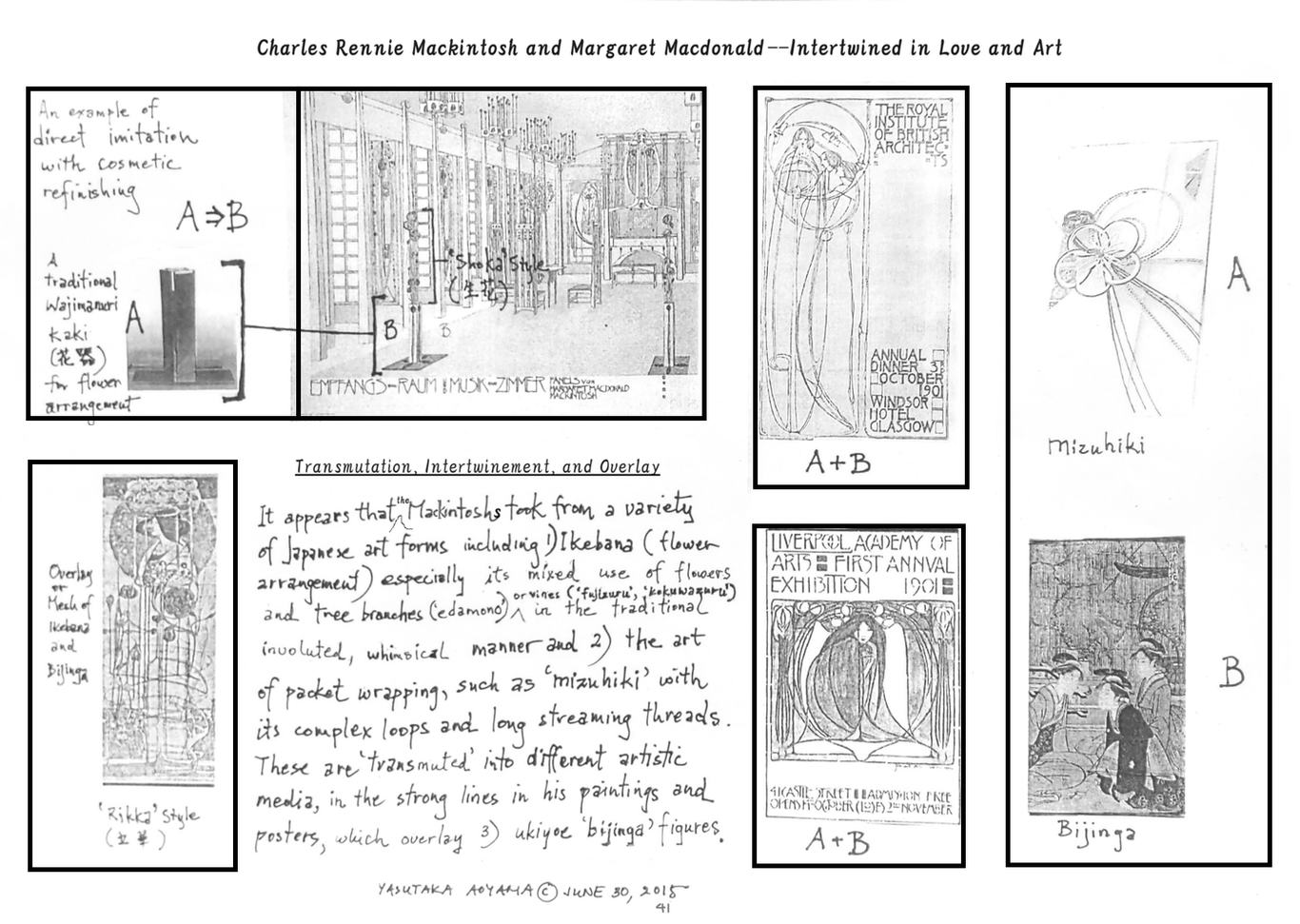

Charles Rennie Mackintosh & Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh

Part II: Transmutation, Intertwinement, and Overlay

Lecture handout, scapebook format, 2015.6.30, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 41

Revisions, editing, and added commentary 2023.9.16 -28

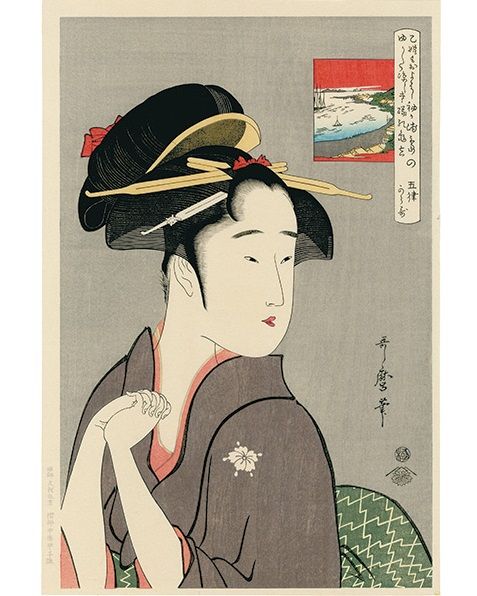

It appears that the Mackintoshs took inspiration from a variety of Japanese art forms including ukiyo-e bijin-ga (pictures of beautiful women, often courtesans), sumi-e (charcoal painting) or suiboku-ga (landscape ink wash painting), and ikebana flower arrangement, especially its mixed use of flowers and edamono (tree branches) or tsuru (vines, e.g. fujizuru or kokuwazuru) in the traditional Japanese convoluted and whimsical manner. They may also have discovered the Japanese art of packet wrapping and decorative tying known as mizuhiki with its complex loops and long streaming threads. These sources were combined and 'transmuted' into art of different media, namely paintings and sculptures, their forms reflected in the strong and multitidinous lines found in their works, those lines often overlaid or fused with bijinga type figures.

The following is an attempt to illustrate the idea, taking a decorative wall hanging (1902) by Charles Rennie Mackintosh as an example, on the right. On the left is the ukiyo-e print 'Unryu Uchikake no Oiran' by Keisai Eisen (1790-1848), the courtesan print that Van Gogh modeled his painting 'The Courtesan' upon. She is in a classic ukiyo-e pose, depicting a female figure in flowing robes with her hair bunched up in the back, poised in a way where she is somewhat sideways with her shoulder accented, jutting towards us, her face at an angle partially hidden.

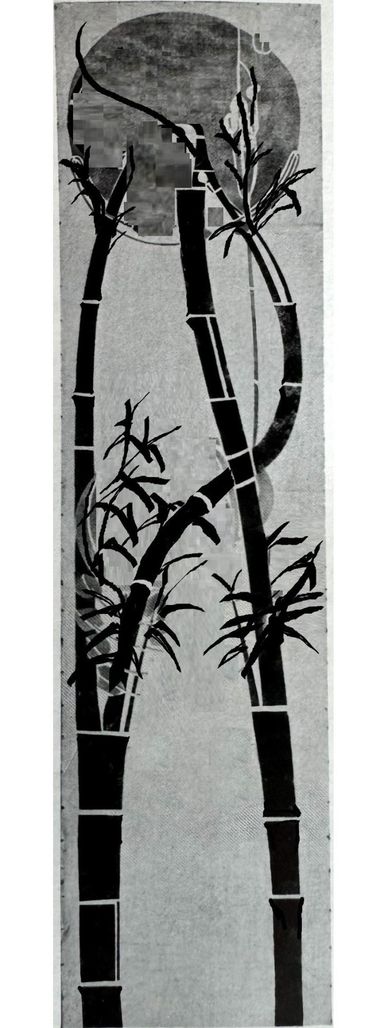

In the center, this author has taken the liberty of creating a quick, kakejiku (hanging scroll) type painting using Mackintosh's picture, making some modifications but relying very much on Mackintosh's original design. More bamboo twigs and leaves are needed, but enough is there to show how close Mackintosh's wall hanging is to sumi-e hanging scroll compositions, including aspects of detail (as the bamboo segmenting or leaves silhouetted by the moon). It seems highly probable that Mackintosh was inspired by sumi-e / suiboku-ga scroll imagery depicting bamboo in moonlight, a common motif in that type of painting. In Mackintosh's picture the bamboo trunks have become outlines of the woman's robe-like dress; a large rose or other flower-like shape sits where usually a mass of bamboo leaves would typically be painted; or otherwise where the bold, focal element of a kimono or uchikake (long overgarment) might be displayed in a bijinga---in Eisen's print it is the face of a dragon, but a large flower or other round shape would not be uncommon.

It is not difficult to see how Mackintosh's image is an amalgamation and entwining, or otherwise an overlaying of imagery, to create something new, which draws from the artistry and emotional content of those very disparate artworks.

Though barely discernable in the bijinga image above (bottom right corner), in the background of the three women is a ikebana display of curving, interwined branches. In Japan flower arrangements have traditionally incorporated the branches, twigs, vines, and leafs of plants much more so than in the West (where flower arrangement until then was basically making a bouquets of flowers) and it was this more primal, vegetative aspect that must have caught the attention of the Mackintoshes, and the complex and convoluted formations that were actively pursued by ikebana artists.

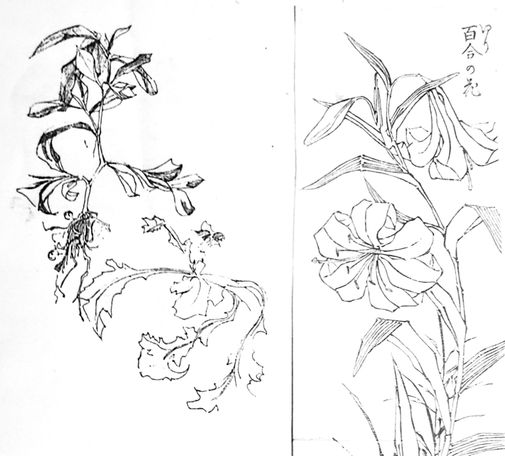

Below: left--his watercolor 'Japonica'; center--a sketch signed a labeled horizontally in Japanese fashion; right--a juxtaposition of a Mackintosh sketch and a Japanese traditional sketch of lilies.

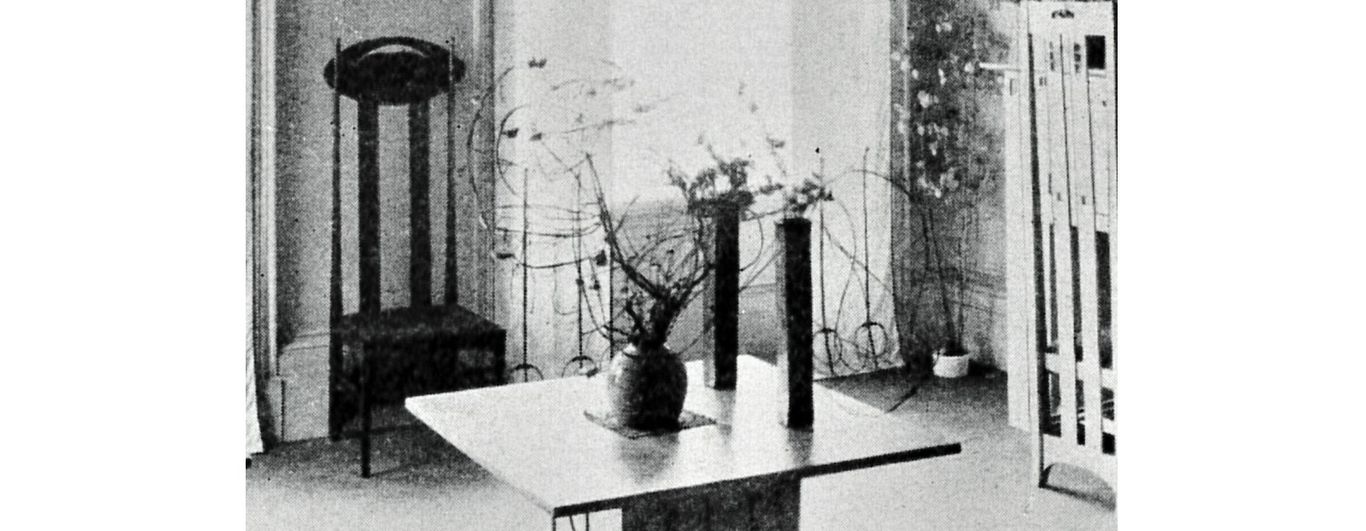

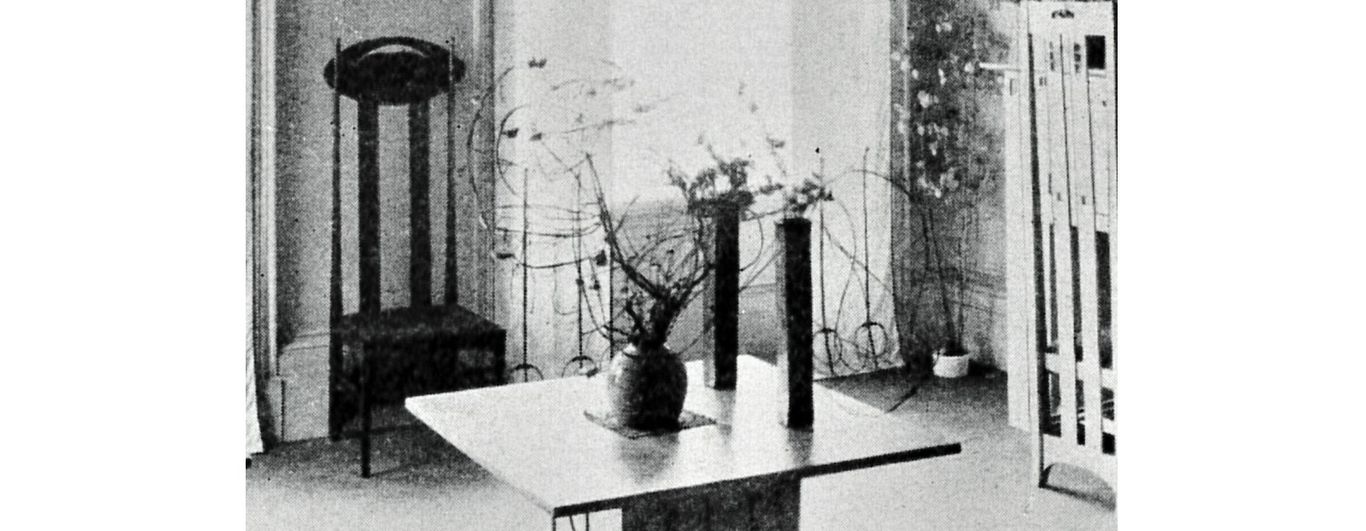

Living with ikebana

It seems ikebana was a heartfelt passion for the Mackintoshes, and not just a device for designs. The Mackintosh studio flat, 120 Mains Street, Glasgow (1900) was overflowing with multiple ikebana-type flower arrangements it seems, as captured in the photo below (from Howarth, 1952). Note the tall, rectangular 'kaki' (flower arrangement container) style vases, peculiar to ikebana in Japan. On the mantlepiece, not visible here, were ukiyo-e prints (See Erin McQuarrie, 'Ma, Mon, Tori-i: The Influence of Japanese art and design on Charles Rennie Mackintosh's masterwork, The Glasgow School of Art'. Glasgow School of Art dissertation.)

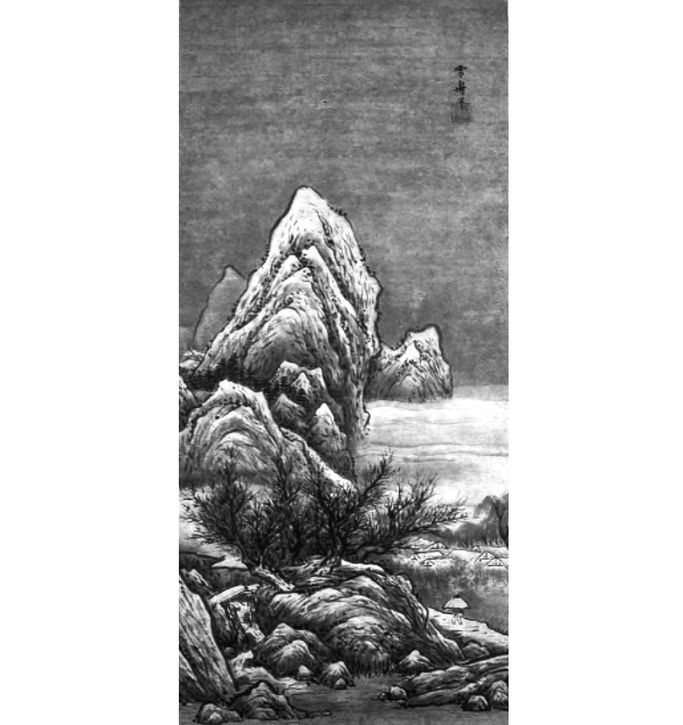

The influence of suiboku-ga, or Chinese style ink wash painting in Mackintosh

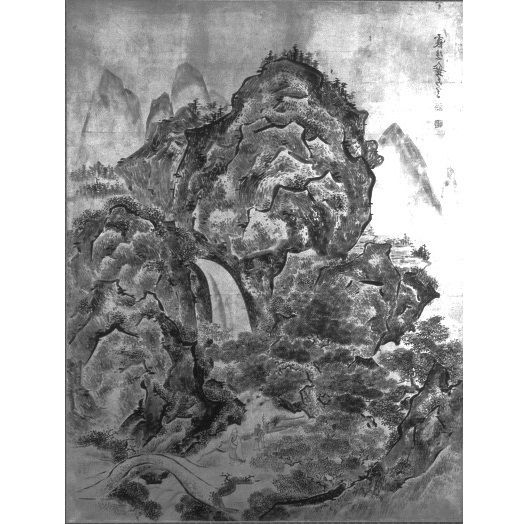

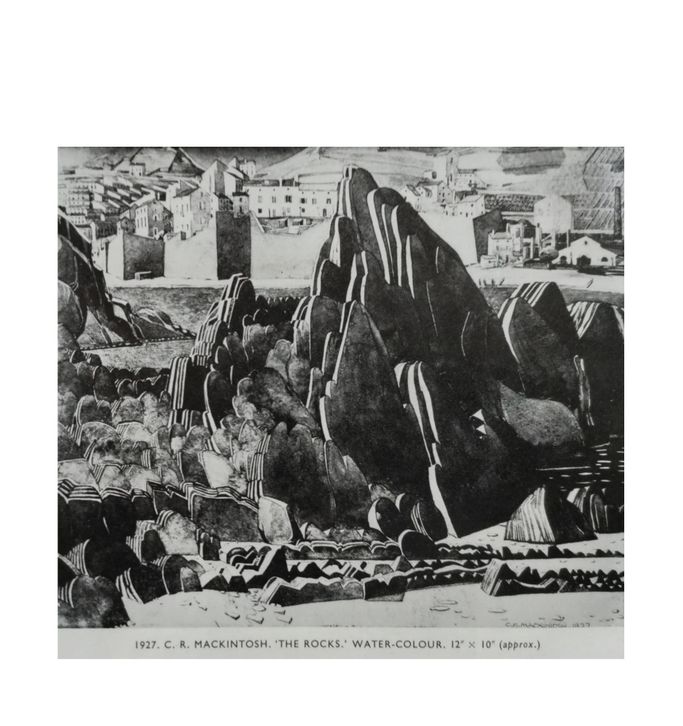

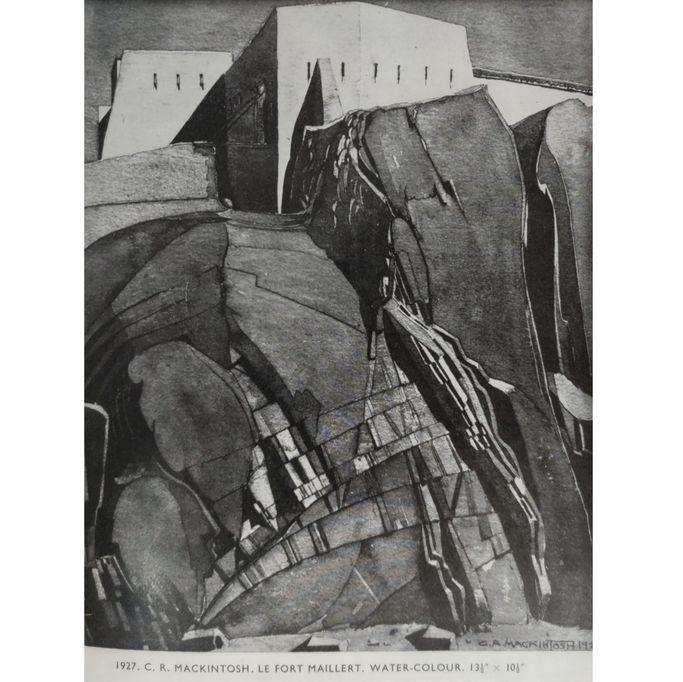

Below: 1) Sesshu, 'Winter Landscape',15th century (Univ. of Michigan); 2) Mackintosh, 'The Rocks', 1927 (in Howarth); 3) Mackintosh, 'Le Fort Maillert', 1927 (in Howarth); and 4) Ike no Taiga, 'Mountain Landscape and a Waterfall', between 1750-1776 (Univ. of Michigan).

Regard the striking similarities, particularly between the first two images. Sesshu (1420-1506), the most renown of Japan's suiboku artists (acclaimed as the greatest painter alive during his stay in China by his contemporary Chinese painters), was prominently featured in books on Japanese art by the early 20th century in Europe and America, thanks to men like Ernest Fenollosa.

The idea that 'rocks' were a worthy subject of painting on their own, that they might be allowed to fill a canvas with little else, and that they were objects of immeasurable aesthetic value, in fact of religious veneration, was of course new to Western painters, and must have been a significant aesthetic revelation. The techniques of painting rock formations was an ancient and well-developed technique in China, and carried on by Japan, whose artists leaned towards either extremely soft (e.g., Uragami Gyokudo and Hasegawa Tohaku) or more sharply formed outlines (e.g., the Kano school and Hokusai's painted landscapes) as found in Mackintosh. The numerous suiboku techniques of painting rock formations, each with a name, and the manner in which Mackintosh has attempted to assimilate them, requires a paper of its own and will not be delved into here in depth; suffice it to say that even to an untrained eye, various aspects of form, shadowing emphasis, over all composition and detail, and what one might call 'directionality' and 'presence', take from suiboku models.

Just to point out a few specific points of interest, observe in Mackintosh's 'The Rocks' how 1) the smaller foreground rocks on a flatter ground surface paralleling those Sesshu, and 2) the creation of open spaces toward which the rocks lean, 3) the various similarities in the grouping of rocks, and of course 4) the similar layering technique of the rock surfaces.

The second pair is a comparison of Mackintosh and Ike no Taiga (1723-76), one of the great 'bujin-ga' (literati painting) painters of the Edo period along with Yosa Buson. While Mackintosh's 'Le Fort Maillert' rock textures might resemble other suiboku works better, the fundamental compositional equivalence of squat, massive, squarish rocky formations, filling up much of the picture space, one taller with a waterfall between them, is worth noting. In Mackintosh's work, the waterfall has been transformed into a vein of the rock itself, but its fluvial origins can be discerned. The classic example of this type of squarish rock formation is Fan Kuan's (late 10th to early 11th century) iconic scroll painting 'Travelers among Mountains and Streams' (谿山行旅図) at the National Palace Museum in Taipei, and which is also characterized by broad, flat rock surfaces.

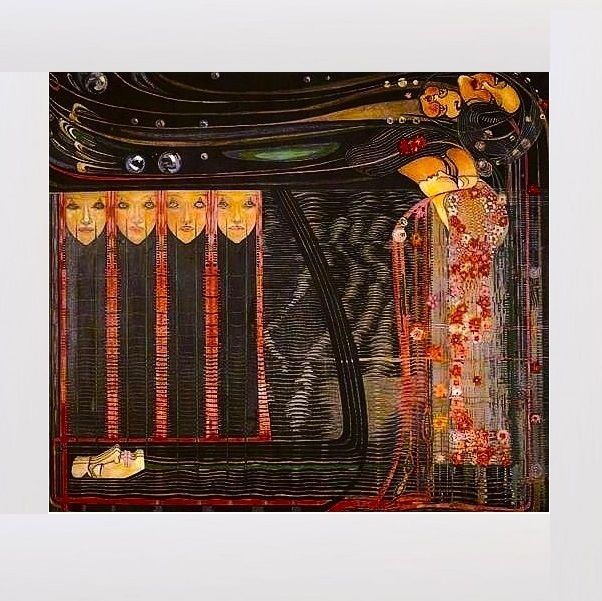

Some further observations regarding Mackintosh's spouse, Margaret Macdonald

Mackintosh's wife Margaret also incorporated various Japanesque qualities into her art, as discussed earlier, and can also be seen in her painting 'The Opera of the Seas' (between 1903-15, whereabouts unverified) shown above. This may be fruitfully compared to the design of Edo period lacquer picnic boxes, such as the one at the Suntory Museum of Art (Tokyo) to the right, for instance. Note the parallels in bold contrapositions of rectangular sections and curving lines; and motifs such the use of bands of scattered flowers and hanging screen-like forms. Regarding the picnic box: "The tiered picnic box was a set of picnic utensils with a handle used on outdoor excursions such as flower viewing parties. ... The design is rich in allusions to Japan's aristocratic court culture including images of court screens used by aristocratic women, the bugaku dance and paulownia combined with phoenix motifs." (Suntory Museum of Art, Iwai: Arts of Celebration, 2007) Both Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Margaret Macdonald looked to Japan as a rich store of inspirational ideas, and as has been emphasized elsewhere on this site, from the early 20th century onward Western artists utilized an increasingly diverse array of Japanese arts and crafts in their work.

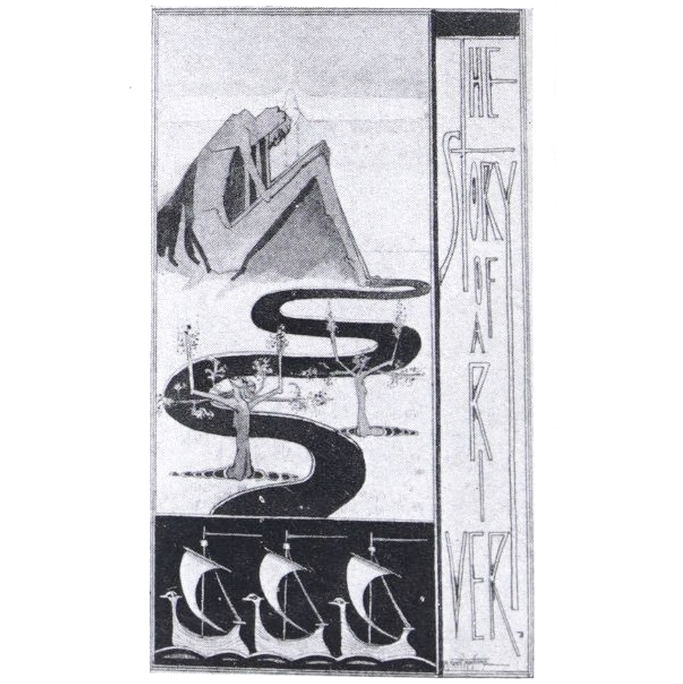

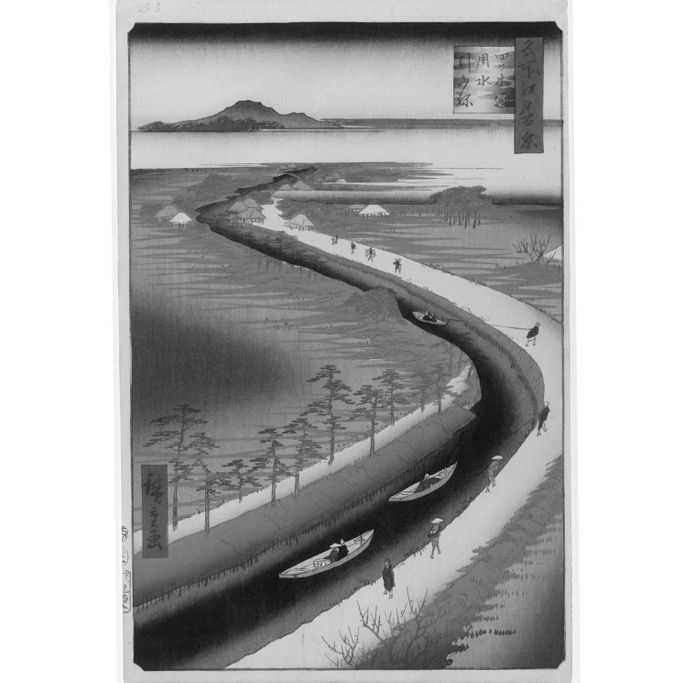

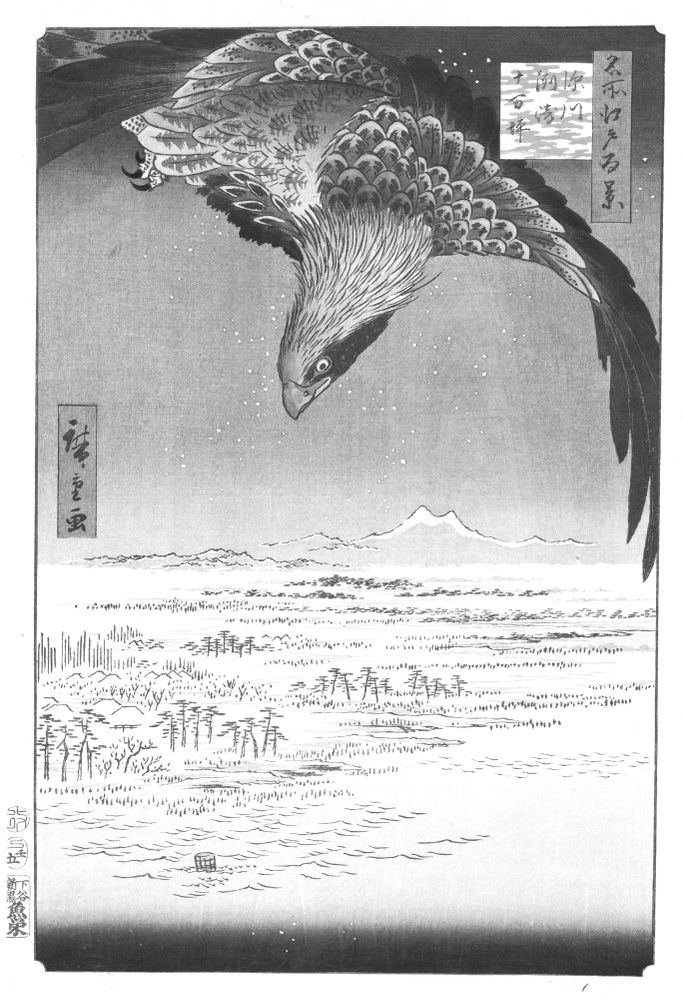

Two other examples of her use of Japanese imagery and the possible Japanese sources are offered below. Left to right: 1) Margaret Macdonald's 'The Story of a River'. 2) Ando Hiroshige's 'Yotsugi dori yosui hikifune' from his series 'Meisho Edo Hyakkei' (hundred views of Edo). Hiroshige's Mount Fuji afar in the background, represented as one higher peak and a lower peak to its right, is transmuted by Macdonald into an enormous resting giant, with bent knee; but the schema is still recognizable as that of Hiroshige's. The title of Macdonald's work is prominently displayed within the picture to the right in a vertical box, a la japonaise. 3) Macdonald's wall plasters for the Willow dinning area look very much like 4) the outfit of a traveling Buddhist monk, to the far right (there are more precisely paralleling priestly outfits, but of which no images were available).

________________________

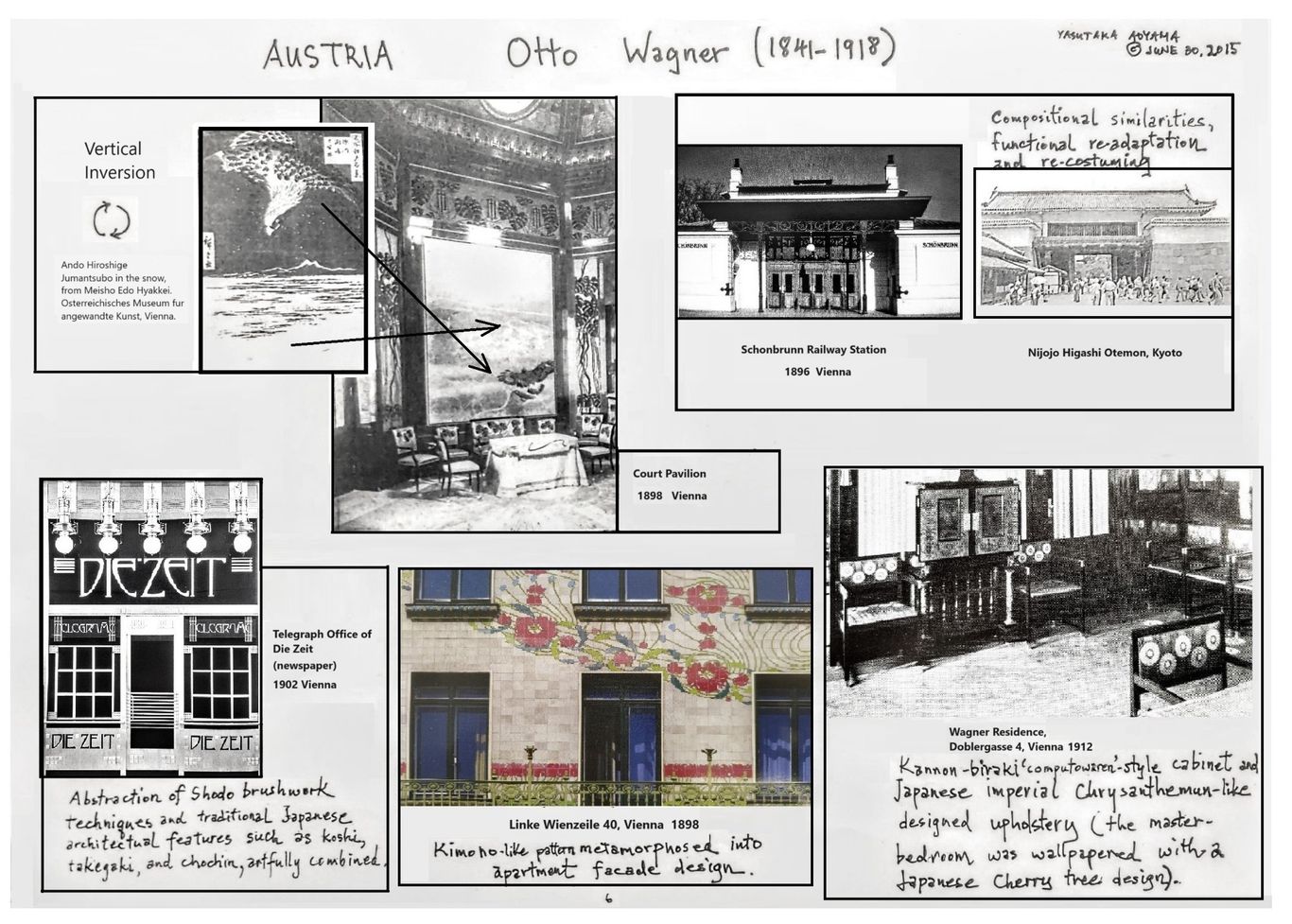

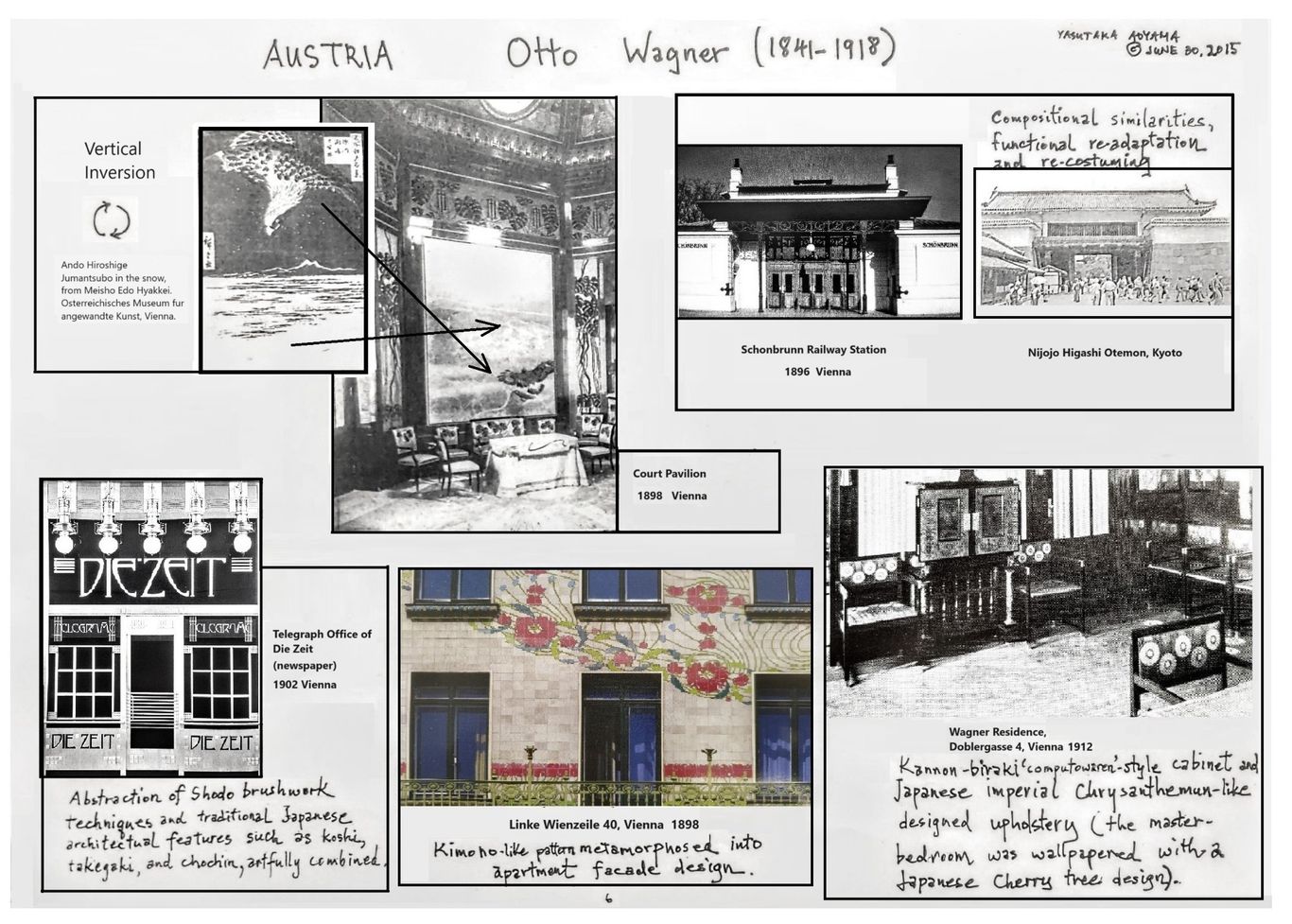

Otto Wagner (1841-1918)

Japonisme as the Epitome of Elegance in a Pioneer of Modern Architecture

Lecture handout scrapbook format 2015.6.30, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 36

Yasutaka Aoyama

"...our sense must already tell us that the lines of load and suppport, the panel-like treatment of surfaces, the greatest simplicity, and an energetic emphasis on construction and material will thoroughly dominate the newly emerging art-form of the future."

Otto Wagner, 'Concluding Remarks' in Modern Architecture, 1896

Otto Wagner's Modern Architecture was a prophetic statement of modernist ideas, and would be echoed in the writings of Adolf Loos and Le Corbusier and in other proclamatory tracts on modern architecture. In Wagner's lines above, it is clear to anyone with a knowledge of Japanese architectonic and constructional principles that those comments are also a perfect description of the fundamentals of traditional architecture in Japan. Otto Wagner was immersed in the japonisme influenced milieu of the Vienna Secession, and his works reflect, albeit in a a masterfully subtle way, the aesthetics of Japanese art and architecture.

As curator of the MAK (Austrian Museum of Applied Arts) Johannes Wieninger writes (in the superbly organized Japonisme in Vienna, 1994), regarding the impetus away from classical styles in Viennese design in the late 19th century, Wagner "is most likely to have been the first one to aim a pointer in the direction of Japanese art. Indications of an artistic nature exist to document this. In his first villa in Hutteldorf, built in 1886, Otto Wagner used Imari vases for the exterior, and put heavy, Meiji-period bronze vases in two large facade niches, which had in fact been intended for sculptures. ... To see in Otto Wagner the first great Japoniste is certainly to exaggerate. But his freer treatment of the European historical vocabulary of forms brought about a drastic atmospheric change, which instilled the young generation of artists in his vicinity with their creativity." ("A Europeanised Japan" Reflections on "Japonisme in Vienna" in Japonisme in Vienna, p. 205.) We might add that to see Otto Wagner as the first great Japoniste is to exaggerate; but to see him simply as a great Japoniste is not at all---and quite apropos.

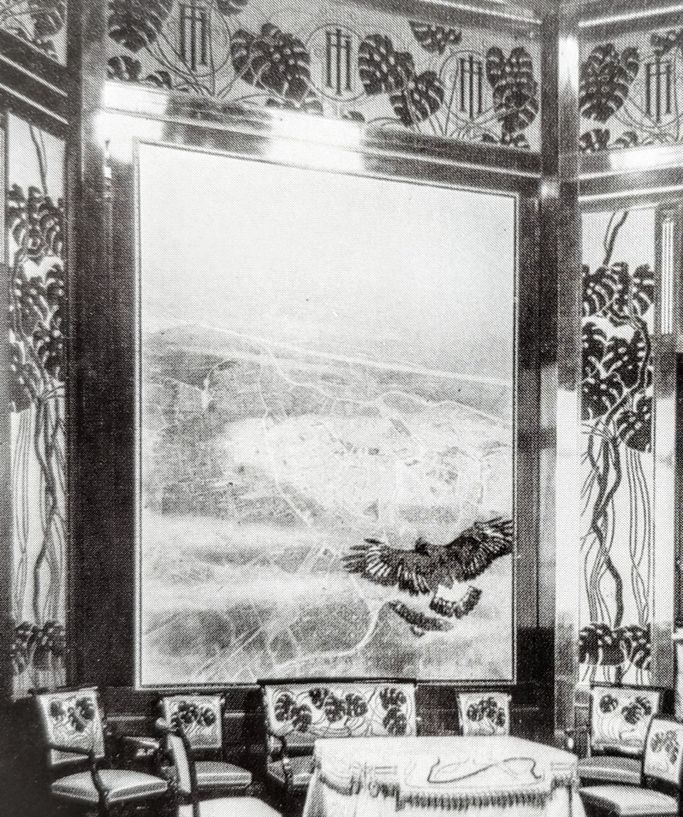

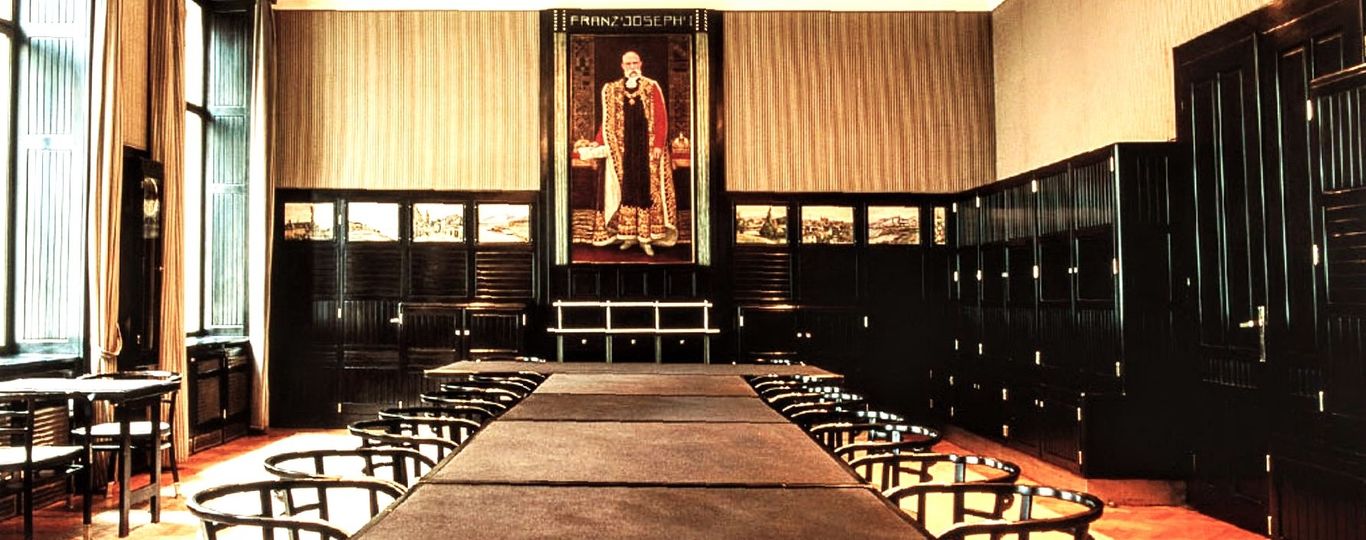

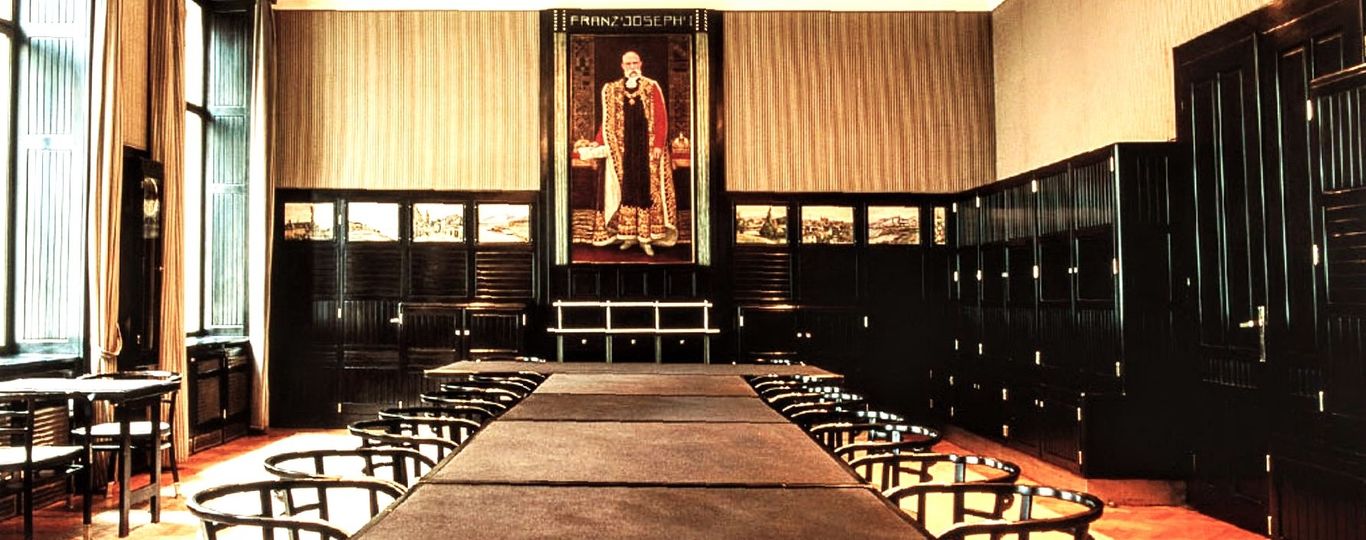

Postal Savings Bank

The Postal Savings Bank (1903-1912) conference hall. Here Wagner artfully blends 'japanned' built-in cabinets with a byobu screen style painting of Emperor Franz Joseph wearing an almost kimono-like robe in rich golds and starkly contrasting red and black.

Let us recall that connected, extended cabinetry, part and parcel of the walls, was an adoption of Japanese interior ideas, and that lacquering furniture black was, like the practice of creating jet black lacquered pianos, also a result of the study of urushi techniques. That influence extends back to the 17th and 18th centuries, when lacquered cabinets were imported into Europe and graced the halls of the German speaking aristocratic and wealthy, as elsewhere in Europe.

Villa Wagner I and Wagner's Kostlergasse Residence

Other aspects of what we might call the 'discreet japonisme' of Otto Wagner. Left: Villa Wagner I (1886) with its shallow sloping and extended eaves with painted undersides characteristic of Japanese Edo period buddhist temple architecture. The four ornamental roof supports over the entrance area also echo Japanese religious architecture. Right: Wagner's city residence, Kostlergasse 3, bedroom wall paper, in classic Japanese style outward 'groping' twigs with ample empty spaces between them. Wagner may be said to be one of the most successful architects in creating an elegant blend of Japanese and Western (and at times Persian) architectural elements.

Shown below is Villa Wagner, extended and painted eave undersides with the four ornamental supports, followed by the painted eaves and four ornamented supports of the 'sanjunoto' (3 level pagoda) of Shinshoji Temple, Chiba prefecture (1712). The style became popular in Japan from the early 18th century, as Buddhist temples sought ways to attract more believer visitations as state patronage waned. This kind of decor was called the 'nokimiage', or literally 'looking up at the eaves'. Wagner also followed the concept in making sure that the visitor would naturally look up at the eaves as he approached, climbing the relatively steep stairs facing the house, making sure the visitor would repeatedly view the painted eaves by angling the next set of stairs parallel to them.

Above Villa Wagner, below Shinshoji Temple.

Vienna Osterriechisches Museum fur angewandte Kunst

Left: one of Ando Hiroshige's most famous prints, also at the Vienna Osterriechisches Museum fur angewandte Kunst. Right: Court Pavilion interior, Vienna. A possible case of image 'inversion', a standard technique of modifying the original image by European japoniste artists.

Majolikahaus

Left, Majolikahaus, Vienna, 1898. Right, Old Imari porcelain, Drick-Messing Collection, c. 1700. Note the extending floral design guided by diagonal lines and smaller budded stems extending diagonally outward (in Wagner upward, in the Imari downward) from the larger flower blossoms, and even the interspaced 'railing poles' ending in bulbs (in Wagner it takes the form of a real rail beneath the wall design) in both. Such patterns were typical of both kimonos and porcelains from Japan, prized by German princes in the first half of the 18th century.

Wagner designed stool

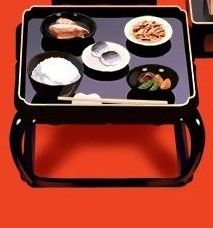

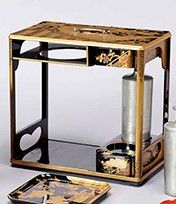

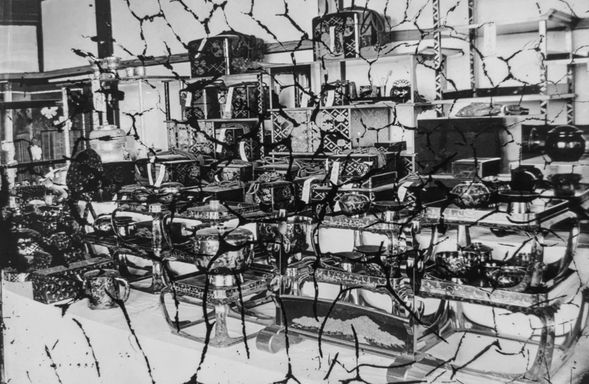

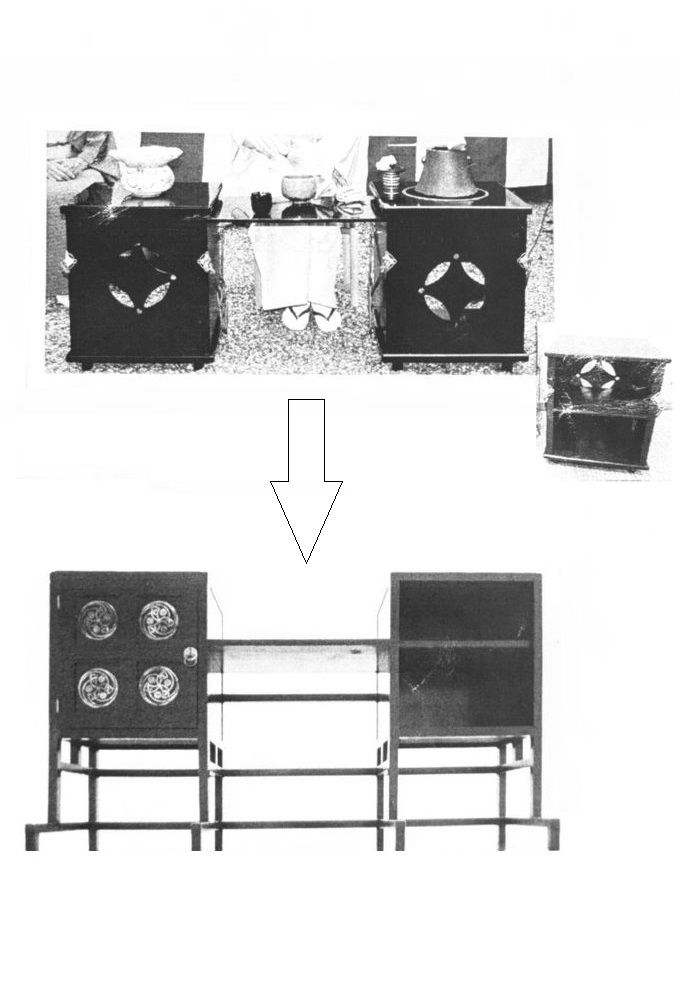

left to right: Two examples of traditional Japanese 'taka-ashi zen' or 'ai-seki zen', followed by a Wagner designed stool, an opened up Japanese picnic box. These sorts of items were often displayed at the world expositions of the 19th century. A photo by M. Moser of one of the Japanese exhibits at the Vienna Exposition of 1872 is shown last extreme right. Though the photo is rather damaged, one can clearly make out the same kind of taka-ashi zen upfront, centrally placed.

The method of connecting the legs and lacquering them black is standard Japanese furniture construction, prevalent because eating, sleeping, etc. was on raised, clean floors, as opposed to Europe, where furniture was raised high away from the ground, and minimal furniture contact with the floor preferred. A classic case of what I call 'functional re-adaptation', from table to stool (just as chopsticks have been used as a hair pin in the West), one of the standard techniques employed by japonisme influenced artists.

________________________

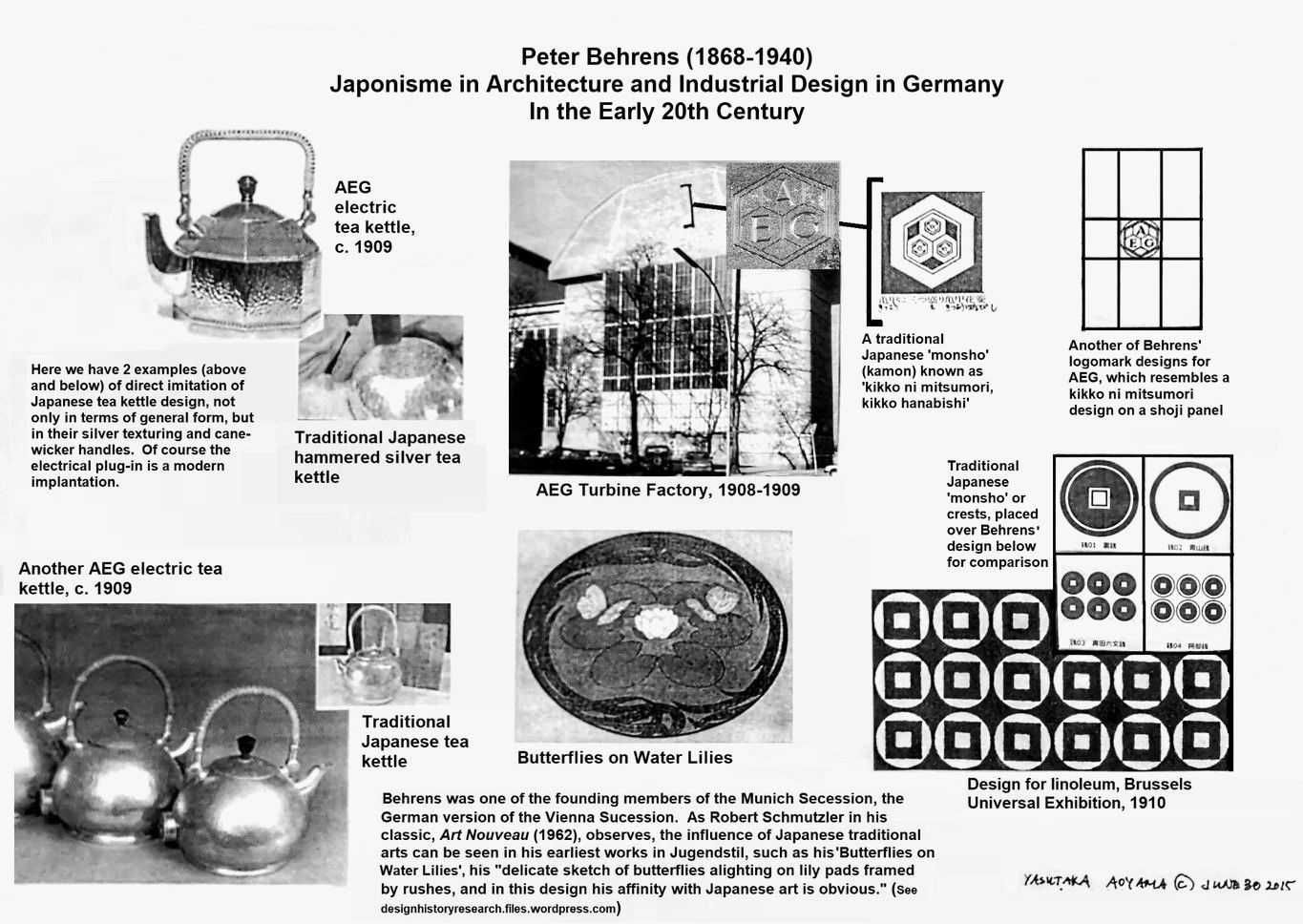

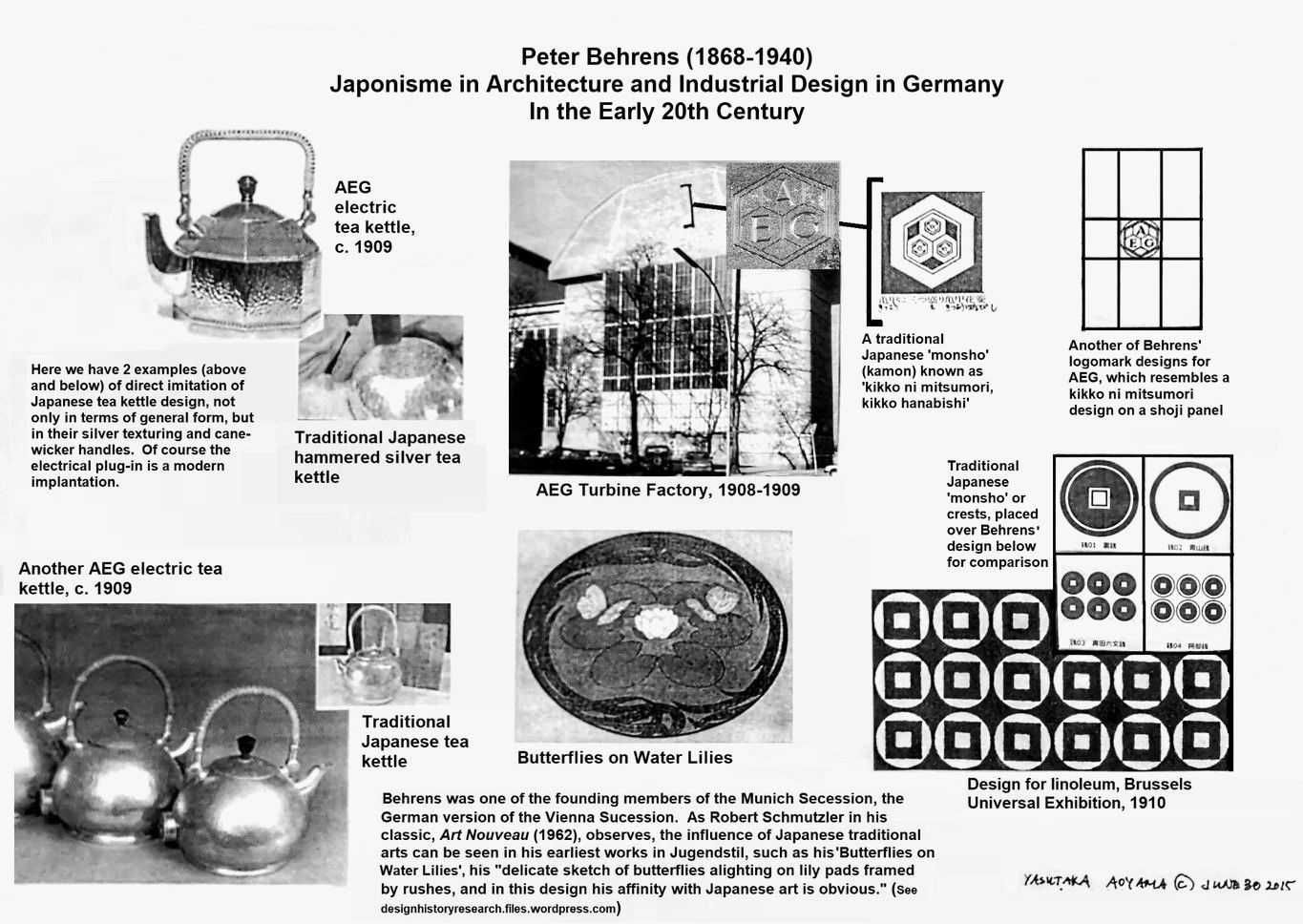

Peter Behrens (1868-1940)

Early 20th Century Japonisme in Architecture and Industrial Design in Germany

Lecture handout 2015.6.30, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 43

Yasutaka Aoyama

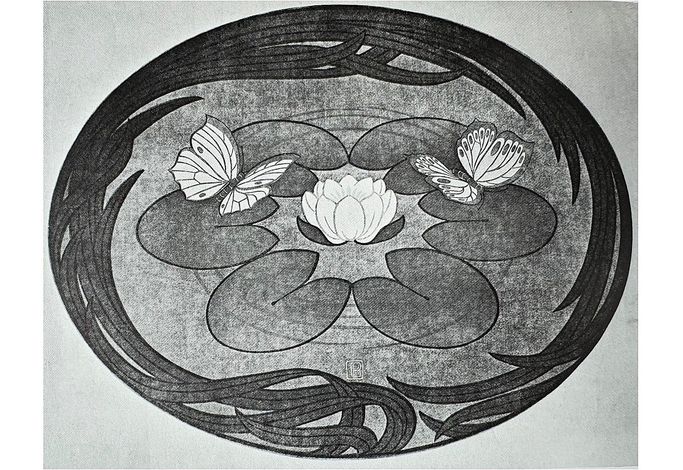

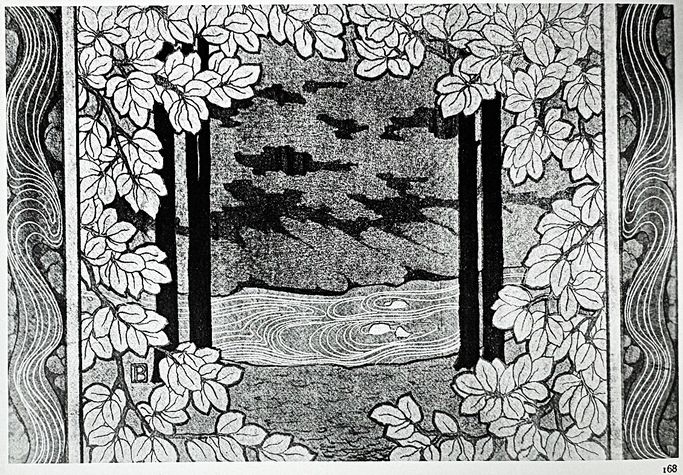

”Peter Behrens (1868-1940) was another of the more important Munich artists to draw inspiration from Japanese objects. The founder of the Vereinigten Werkstätten (United Workshops) in 1897, Behrens, like Eckmann, had also started his career as a painter and designer, then turned to the applied arts, where he chiefly designed carpets and furniture, and at last arrived at architecture, a field in which his work carried him far beyond Jugendstil into the realms of what can be called the modern art of building. His earliest works in Jugendstil are ornamental drawings like the delicate sketch of butterflies alighting on lily pads framed by rushes [shown below left], and in this design his affinity with Japanese art is obvious. ... The color lithograph, The Brook [shown below right], shows a highly abstract stream in the flat Japanese style flowing between tree trunks and framed by large leaves.”

---Robert Schmutzler, Art Nouveau, 1962, 1977 abridged edition, p. 153

Photos from R. Schmutzler, Art Nouveau, 1962, 1977.

Note also the signing in the Japanese ukiyo-e print style of lettering within a block, barely visible in the lower center of the water lilies sketch, and more distinct in The Brook, found in the lower left of the lithograph, nestled among the leaves. The butterfly sketch looks very much like it was based on a Japanese lacquer 'o-bon' tray; while one of the brook appears to be a melange of katagami-type patterns and a central image that once again is reminiscent of lacquerware iconography.

Peter Behrens surely must be included among those German architects influenced by Japanese design including that of lacquerware, but especially monsho crests, katagami patterns, and metal crafts. His interest in Japanese arts and crafts was especially strong in the 1890's during his years in Munich, and he himself owned ukiyo-e prints. (Behrens bio in Katagami Style, 2012, Mitsubishi Ichigokan Museum, eds., supervised by Mabuchi A.)

_______________________

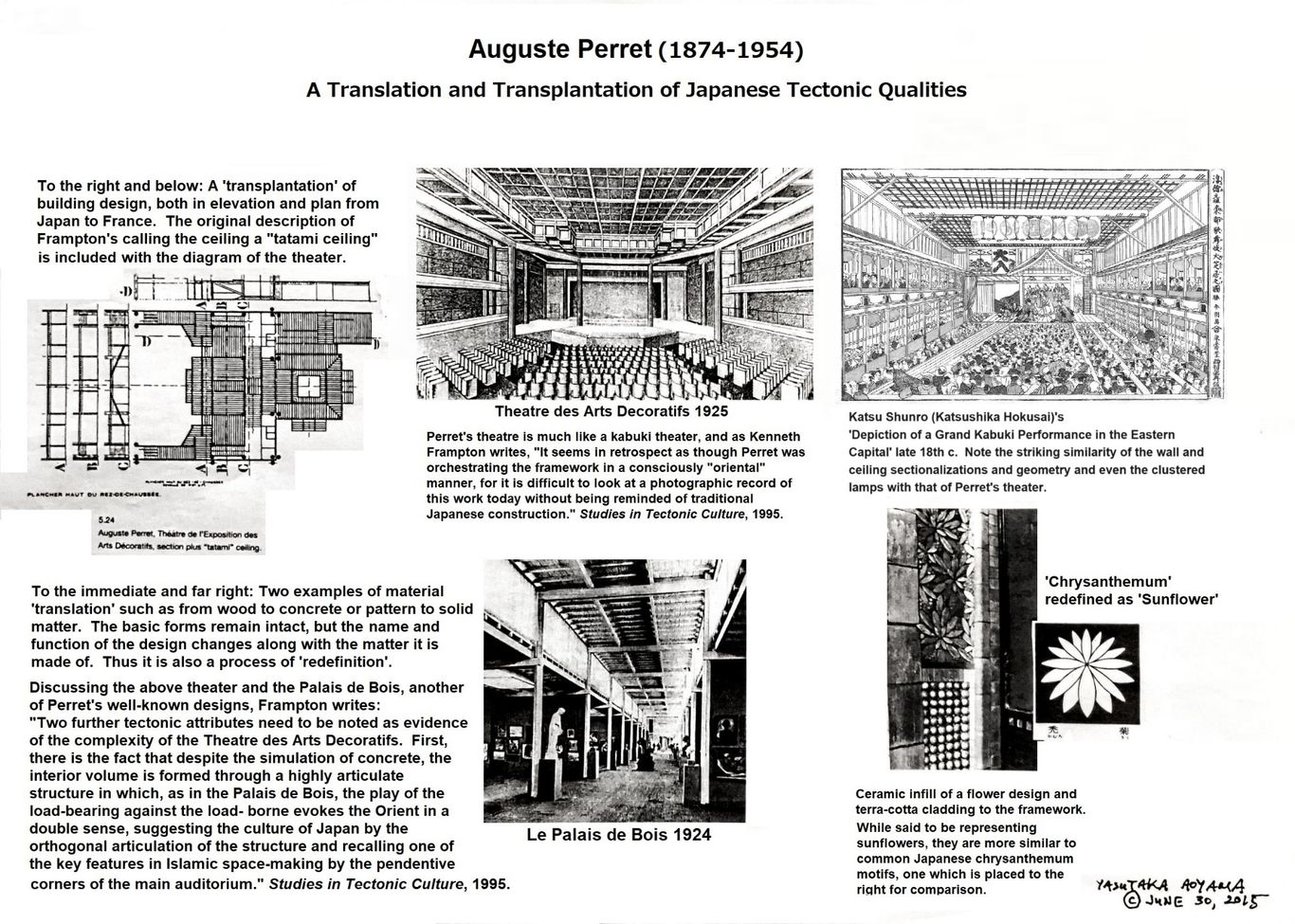

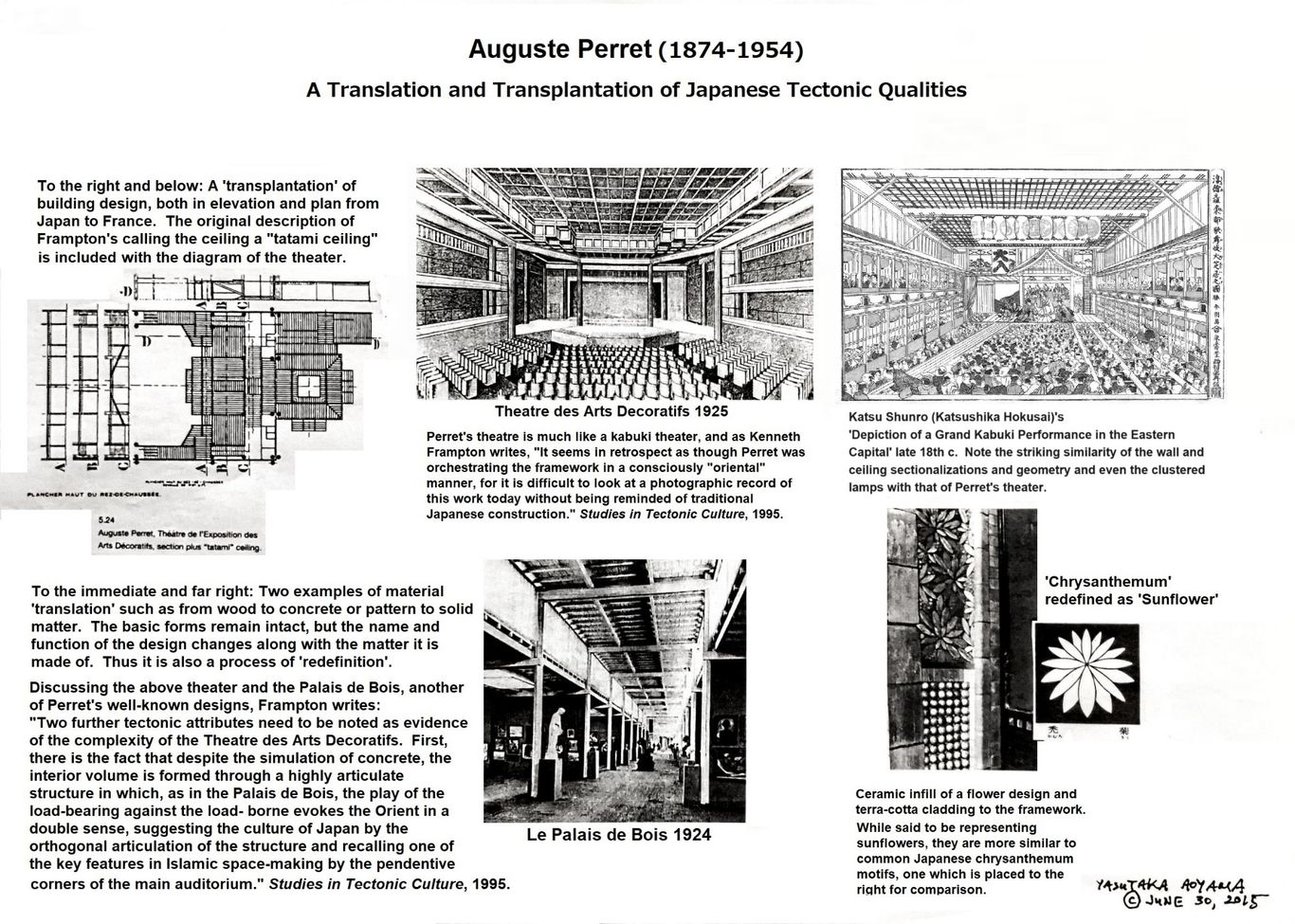

Auguste Perret (1874-1954)

Lecture handout 2015.6.30, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 44, revised 2024.5.23

Yasutaka Aoyama

The following text added 2024.9.17.

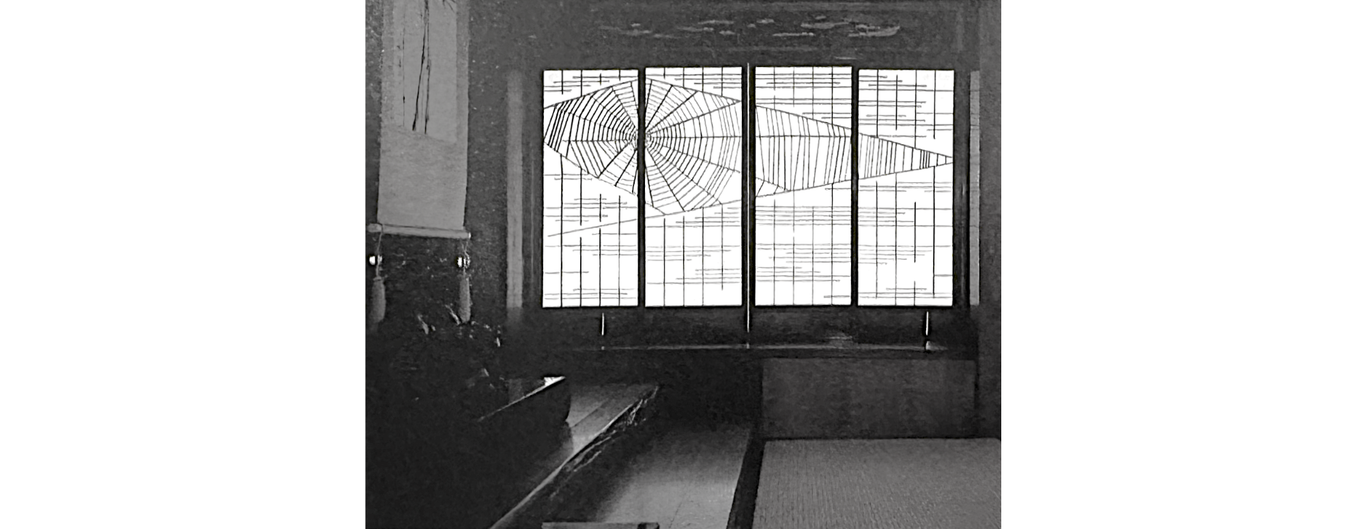

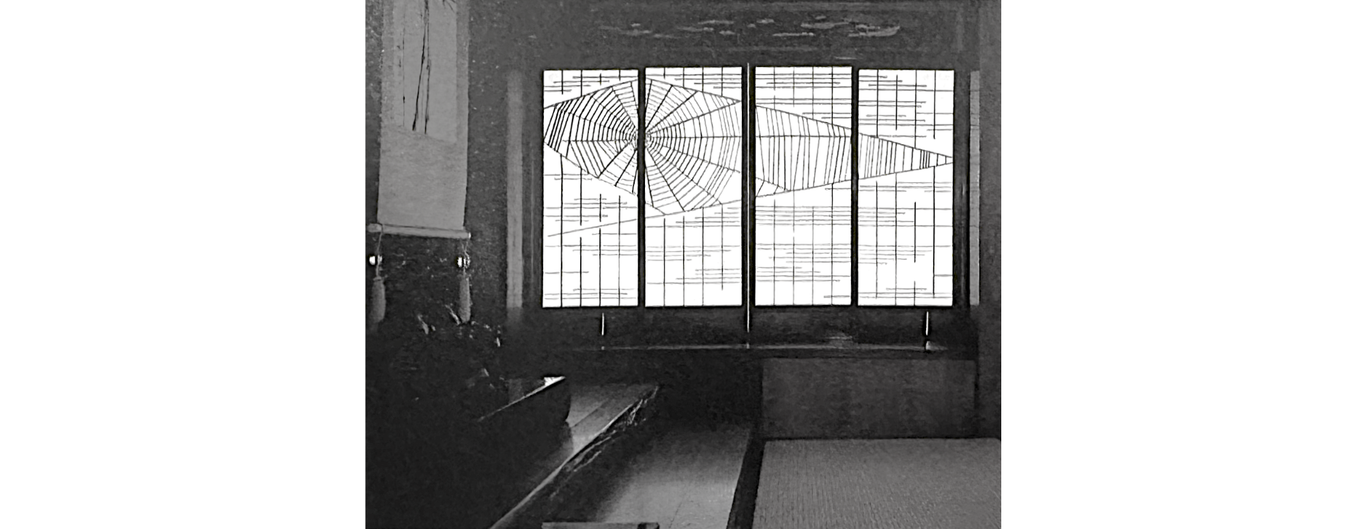

The same kind of Japanese architectural characteristics of the repeating grid, whether reminiscent of the shoji (the gridded sliding screen door) or gotenjo (ceiling with gridded with interlocking framed square panels) or tatami (interlocking rectangular floor mats), in combination with finer inconspicuous Japanese decorative elements, is seen also in his façade design for the Garage rue Ponthieu, Paris (1905), one of his best-known buildings.

At first glance, from a distance, the large, dominating central cathedral rosette-like window does not give a Japanesque impression to the viewer. But that is the same with his apartment house on rue Franklin, Paris (1903) as well; it is only when one looks at the details of it close up that one sees distinctly Japanese decorative motifs embedded into the design (e.g. the example above of the sunflower/chrysanthemum motif that is distributed on the exterior of the rue Franklin apartment). The central rosette-like window glass panels of the rue Ponthieu facade, on closer examination, each section varying in the glass texturing, is analogous to Japanese kumiko (extremely intricate geometrically patterned wood fretwork) that is fitted into shoji screens, where the larger, thicker koshi (framing wood pieces) section off different types of kumiko patterns.

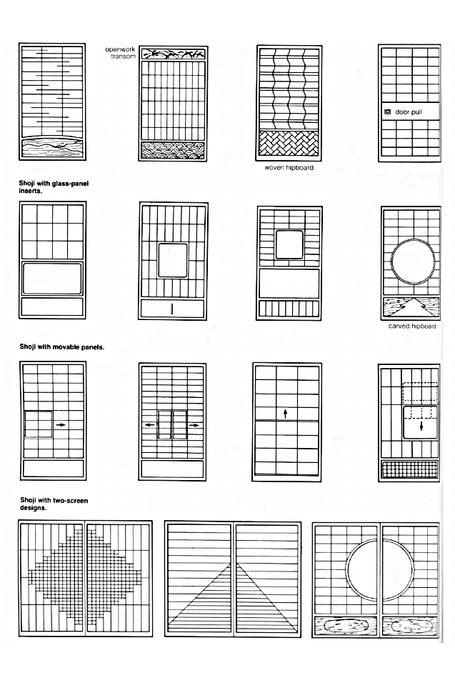

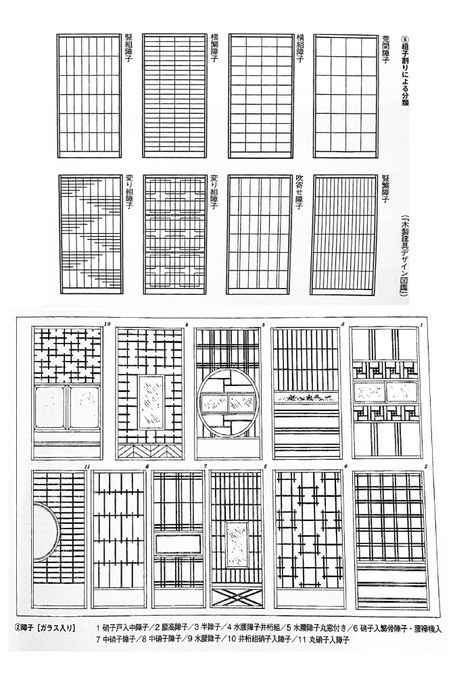

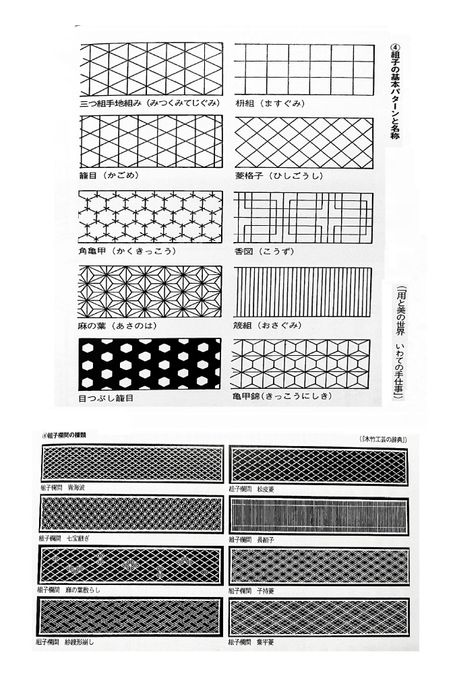

In other words, the whole front façade design is analogous to a giant shoji screen in which one fourth or so is often devoted to complex kumiko. Particularly in the early Meiji period, shoji designs started to veer off in varied directions in terms of composition and patterns though these are unfamiliar to most Westerners as well as to present day Japanese. Shoji came to be designed with a variety of whimsical motifs or shapes such as spiderweb designs, more centrally placed in the screen. While the intricate design of Perret's stained-glass windows of his Notre-Dame du Raincy may seem more Islamic or Indian in its ornamental style, and either may have been the greater influence there, for the works discussed here, and in his other works besides the church of Raincy, the composition of the gridwork along with other aspects of his designs are more akin to that of Japanese architecture.

Below is a limited sampling of shoji and ranma designs. These sorts of grids and patterns covered extensive 'wall' surfaces, with a wrap-around effect reminiscent of Perret's designs. Note that these pattern variations, numbering in the hundreds, if not thousands, usually had established names. This is something that indicates the traditional and widespread nature of this type of designing in Japan; what was commonplace in one culture may be celebrated by its novelty and rarity in another as modern and avant-garde.

Photo captions and sources to be added.

________________________

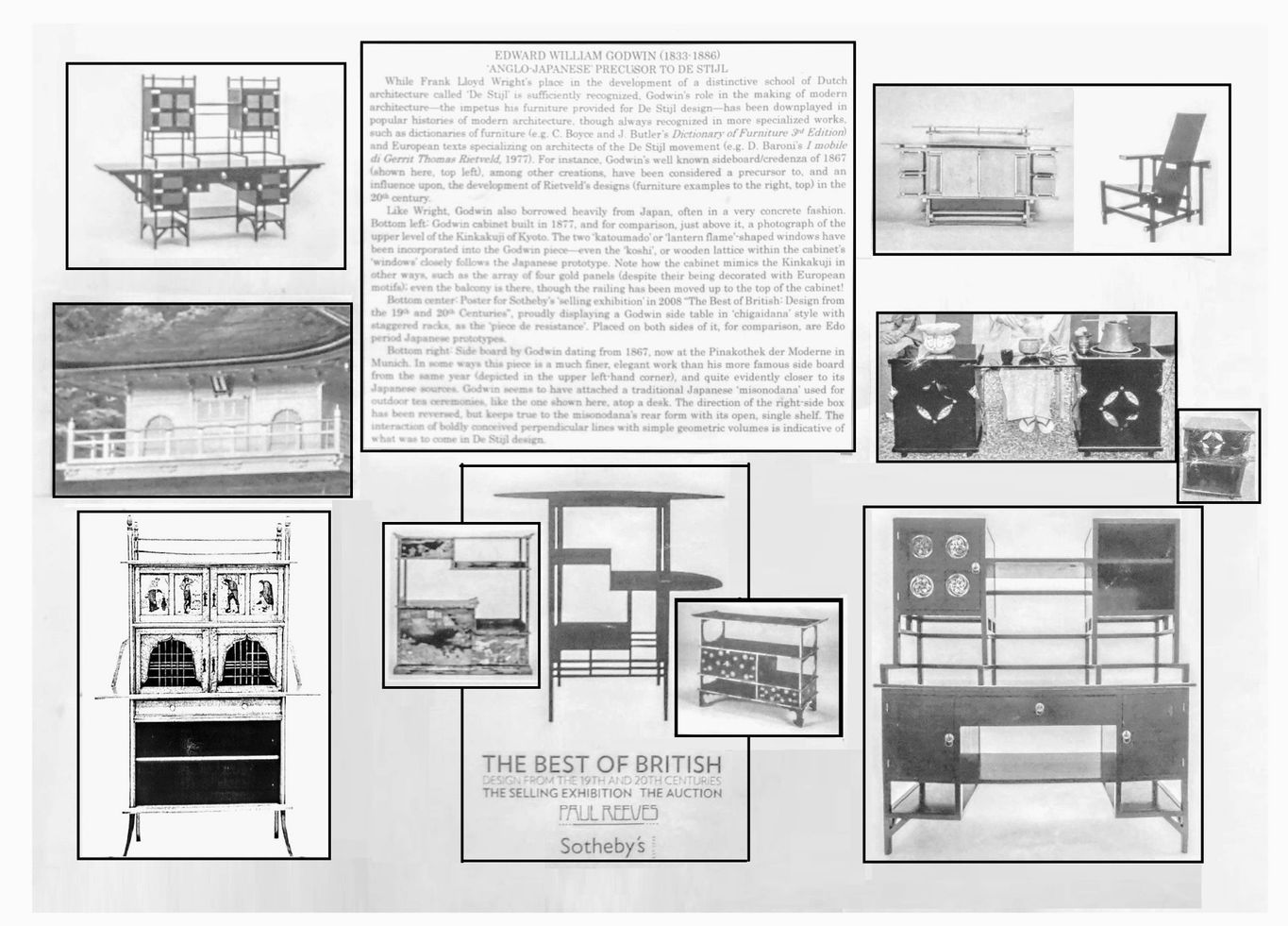

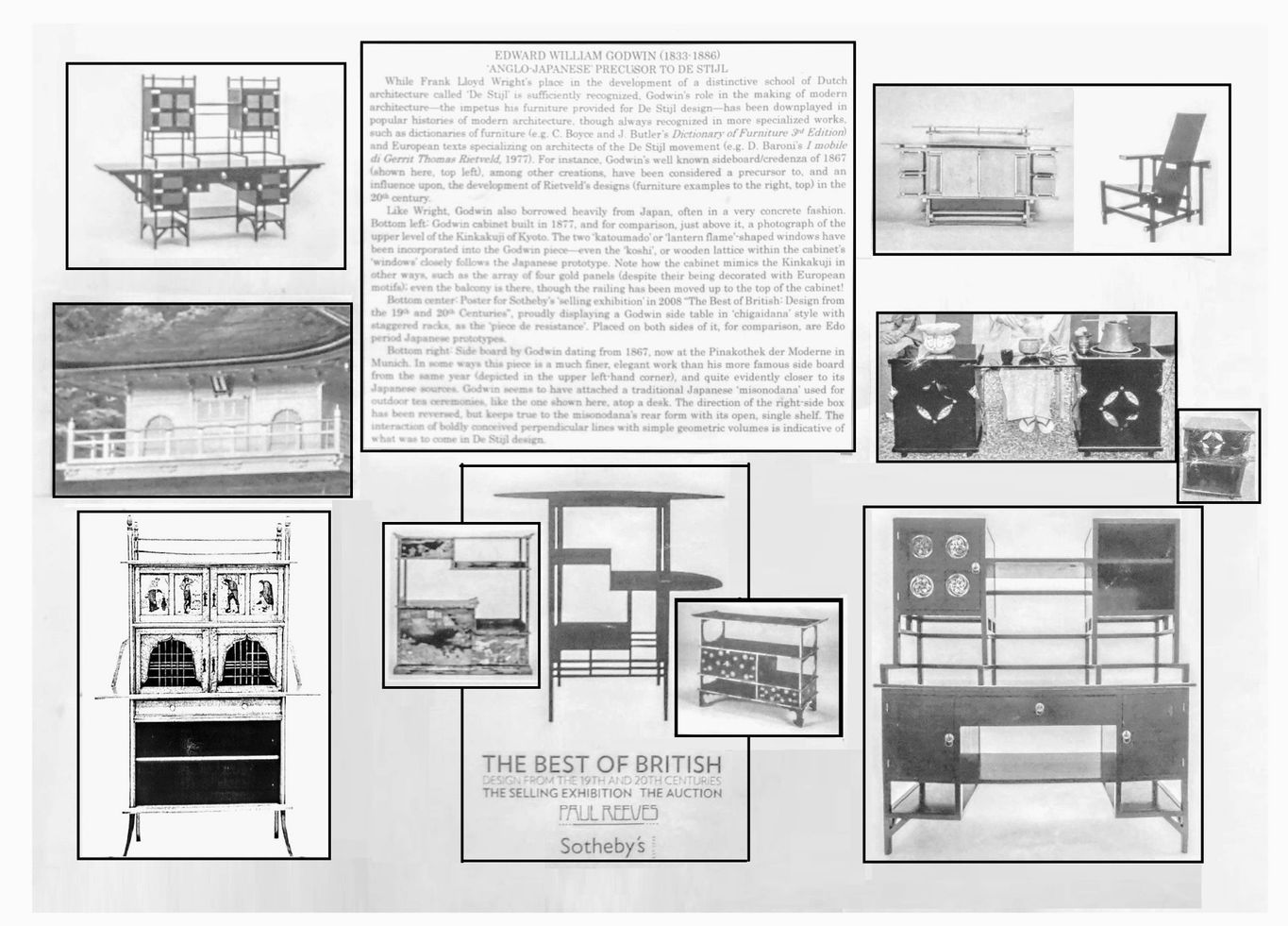

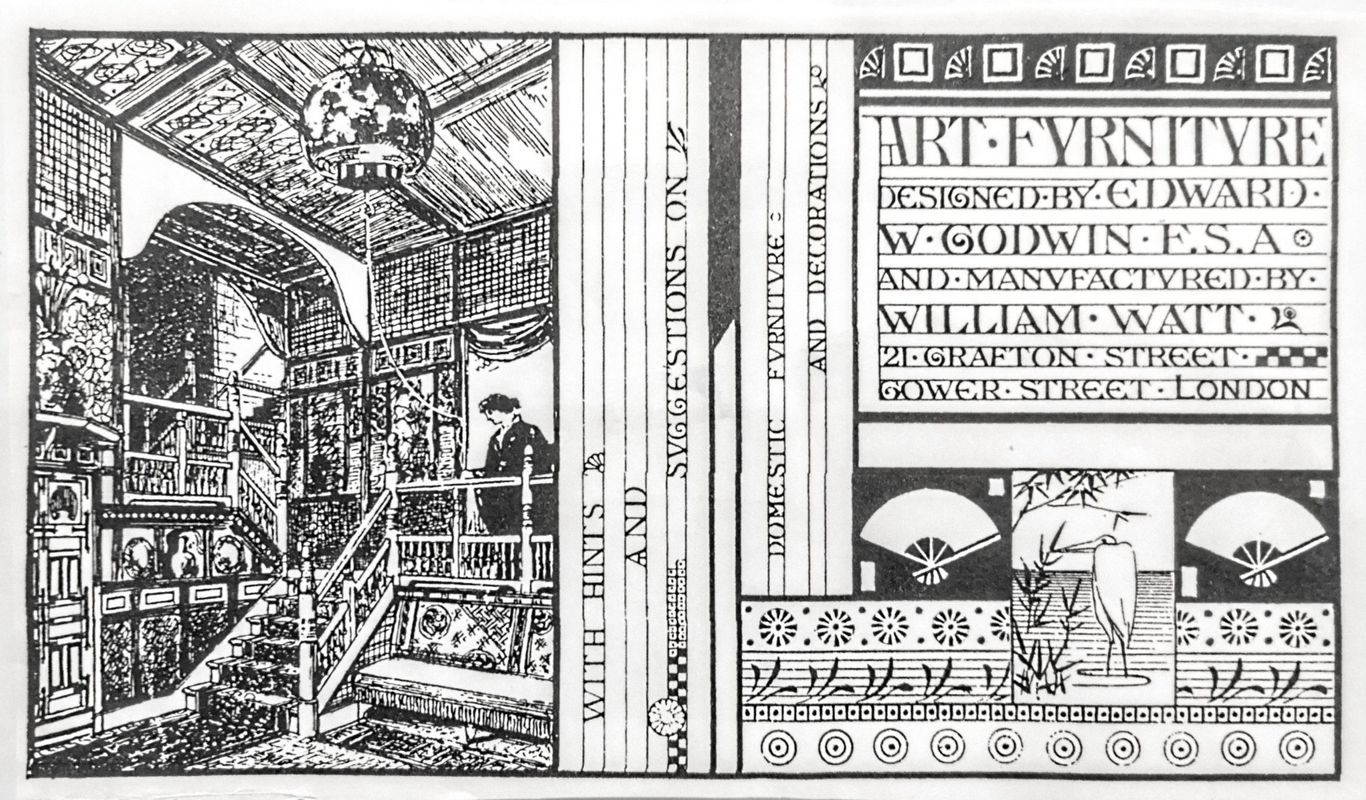

Edward William Godwin (1833-1886)

Anglo-Japanese Precursor to De Stijl

Prepared 2015.11.23, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 45

Yasutaka Aoyama

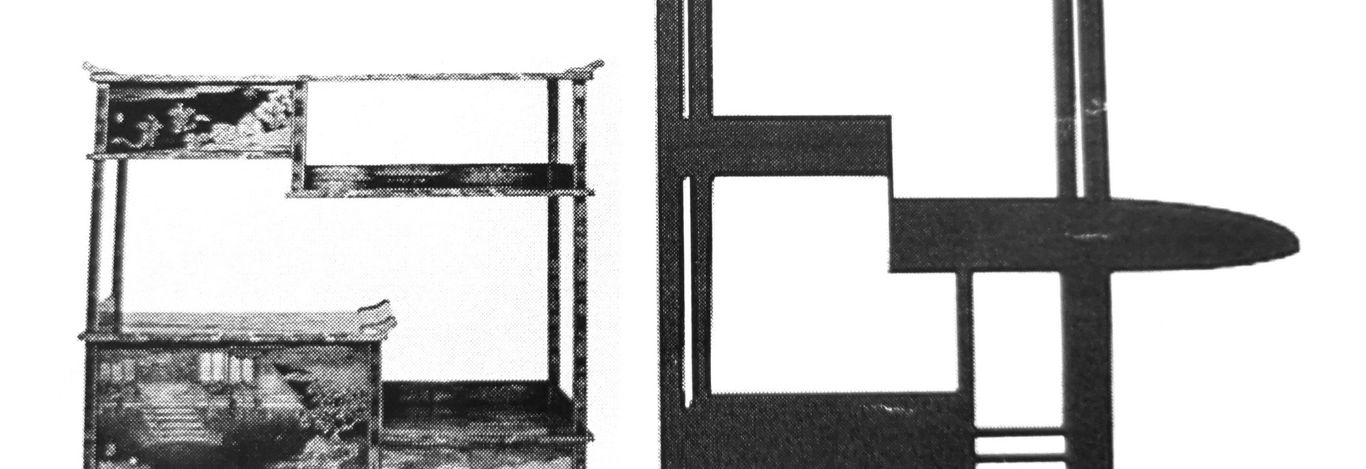

Key Points of Comparison

Left: Japanese traditional furniture, with 'chigaidana'. Right: Godwin furniture, in chigaidana style.