Under construction

2024.12.12

Uploaded 2024.12.19

オディロン・ルドン

象徴主義のジャポニスム——絵画に映る日本工芸・巻物のイメージと色彩感性

Odilon Redon (1840-1916)

Kogei and Makimono Japonisme in Symbolist Imagery and Chromatics

Yasutaka Aoyama

"How did Japonisme come to evolve so rapidly, last so long, and inspire so many to active participation as collectors? ... The prevalent type among them possessed four characteristics to a marked degree: entrepreneurial spirit, a developed artistic sensibility, a nose for coming trends, and an appreciation of decorative ensemble. ... For these Parisians were as firmly grounded in the world of craftsmanship as in that of art; perhaps without realizing it, they were looking for a bridge to link the two. They admired Japanese ceramics, precious lacquer, exquisite metalwork from sword-hilts to jewellery; and all these were represented in their collections alongside prints. They chose their objects for quality, rarity, luxury." (Berger, 1992, p. 177)

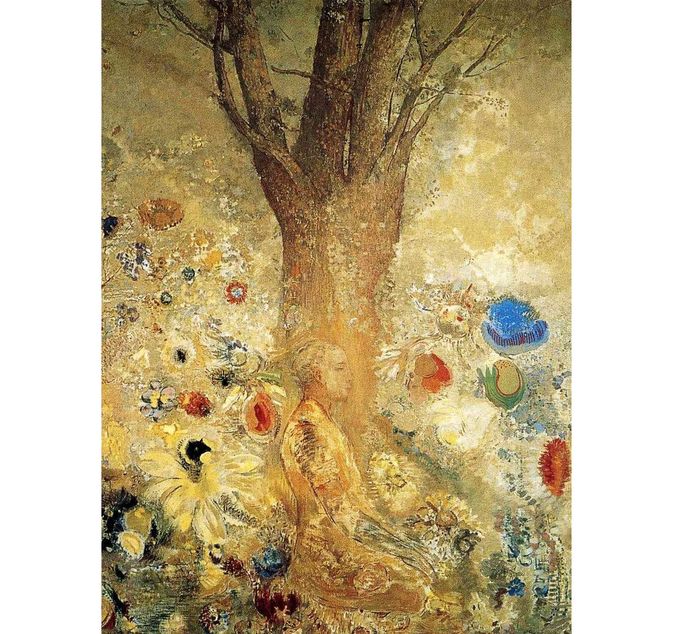

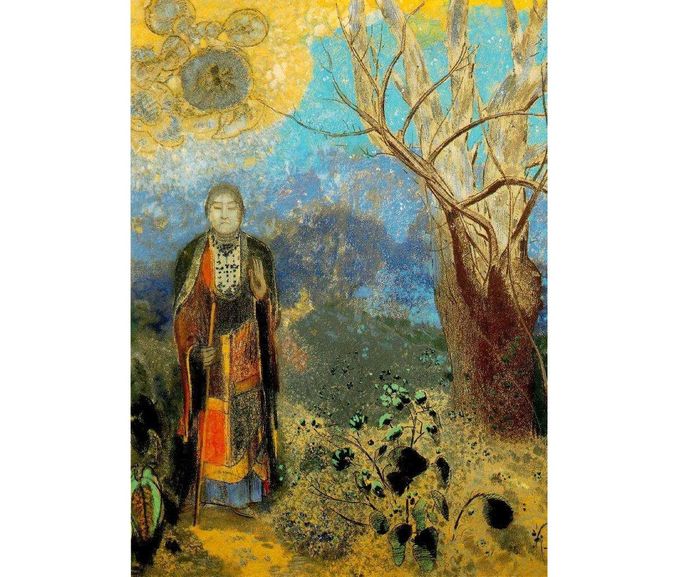

The word 'crafts' (similar to shugei 手芸), simply does not do justice to the type of Japanese artisanal works mentioned above, and the Japanese word for such arts, 'kogei' (工芸), will be used instead, which carries no implications of being inferior to 'fine art', as crafts are in the West. The debt 20th century modern painting owes to Japanese ceramics has been discussed elsewhere on this website in regards to Mark Tobey and mid-century abstract painting, but precedents can be found from at least a half century earlier in the Jugendstil / Vienna Secession artists as Klimt, and in Symbolist / Expressionist painting, as exemplified in the work of Odilon Redon.

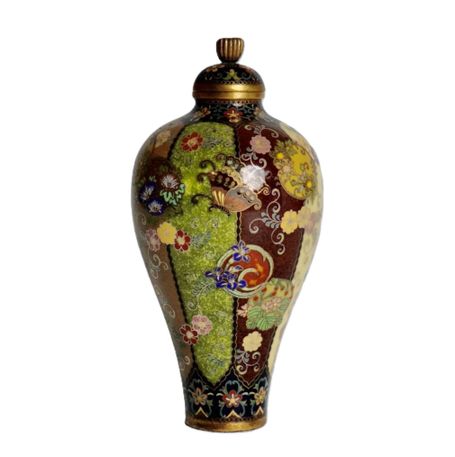

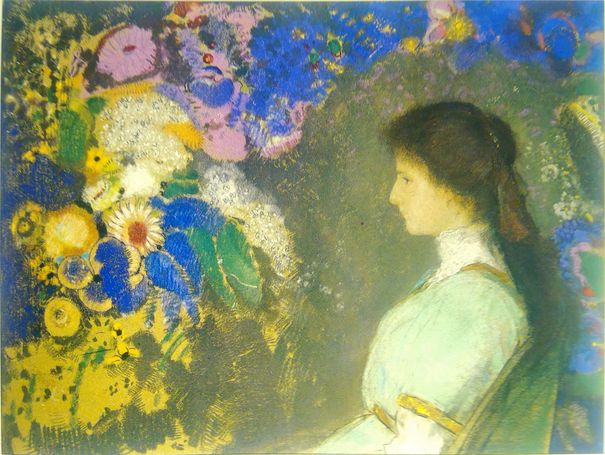

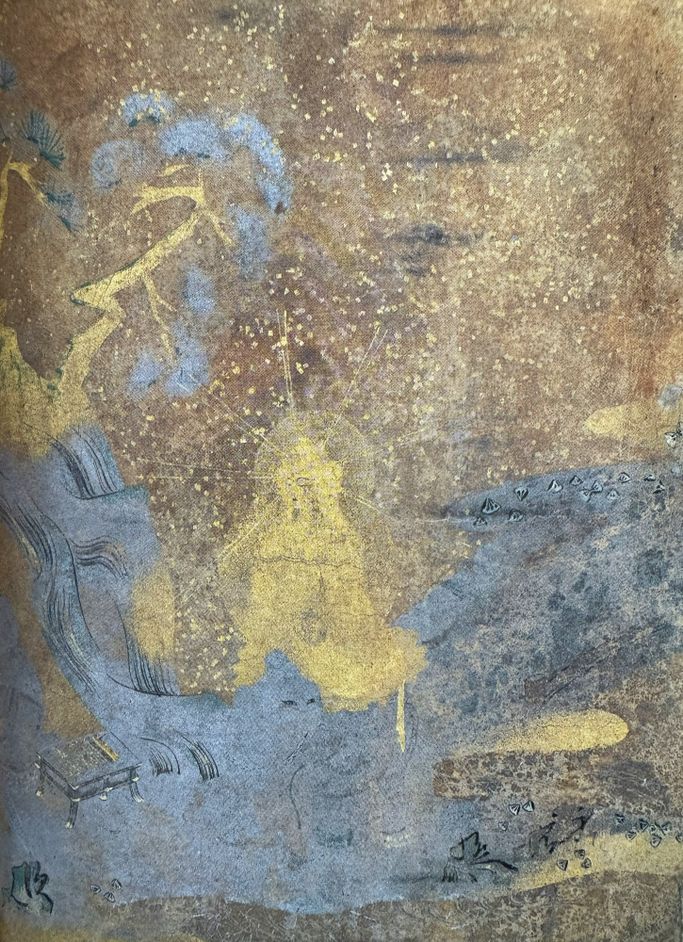

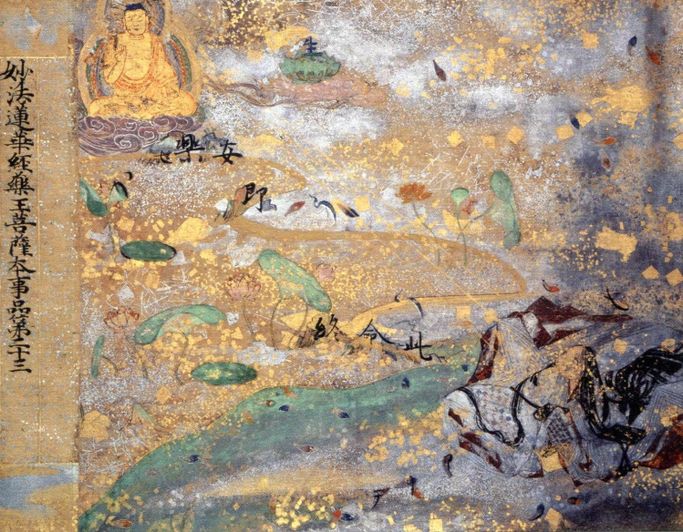

Redon's japonisme has been well-researched and discussed primarily in the context of ukiyo-e prints, which will be touched upon at the end of this article. Hardly recognized is the equally important, if not more important, influence of Japanese kogei on Redon's imagery and chromatic qualities, such as pottery (especially cloisonne), as well as decorated and illustrated and books or scrolls 'makimono' (巻物) especially decorated sutras (装飾経) or poetry collections (歌仙集) in chigiri-e (ちぎり絵, 'torn' and pasted, decorated washi paper) form, and probably yamato-e byobu screens and maki-e lacquerware as well---the type of items that were avidly collected in Paris by the great collectors referred to above, accessible to those in artistic circles, and if not seen firsthand, illustrations of which were abundantly produced in the artistic publications of the late 19th century, and onward, as in the Louis Gonse organized 1883 Exposition rétrospective de l'art japonais of some 3,333 Japanese art objects from 26 collections, highlighting ceramic works, marks the heightening interest in Japanese ceramics and other art forms besides ukiyo-e, with a growing appreciation for "exquisite workmanship and subtlety of form" (Berger, 1992, p. 185).

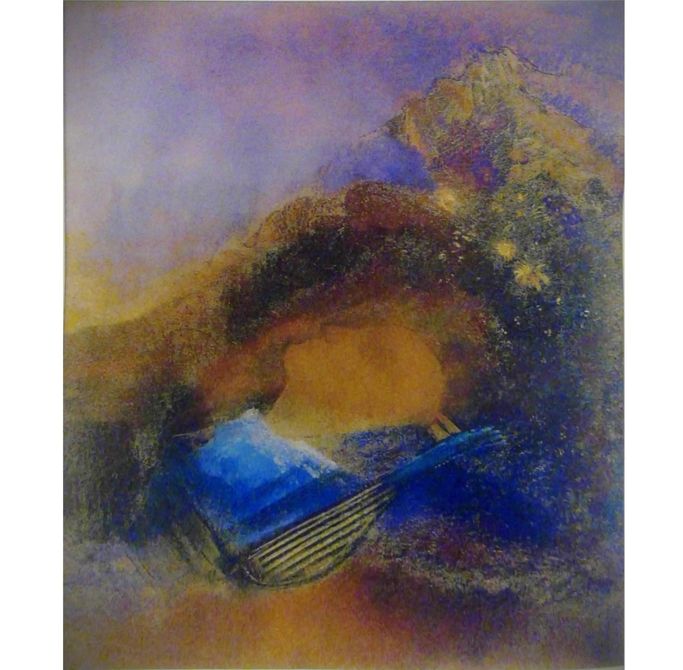

Both in terms of specific imagery and chromatic qualities (such as color tones, color combinations and techniques of color distribution), Redon's paintings, especially from the early years of the 20th century onward, clearly reflect aspects of export oriented Japanese porcelains, especially cloisonne porcelains, as well as other Japanese kogei decorative techniques such as maki-e and chinkin (沈金) used in lacquerware, as well as related techniques of illustrating scrolls using gold and silver powder or leaf (金銀粉/金箔), of which the Heike Lotus Sutra is perhaps the most famous, inspiring many other similar works and copies over the years up to the early 20th century.

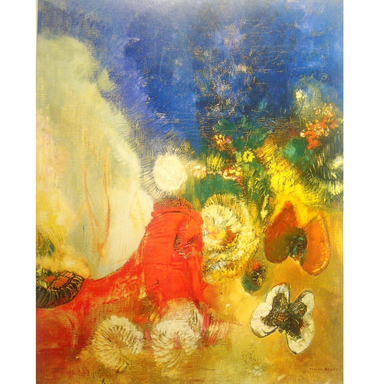

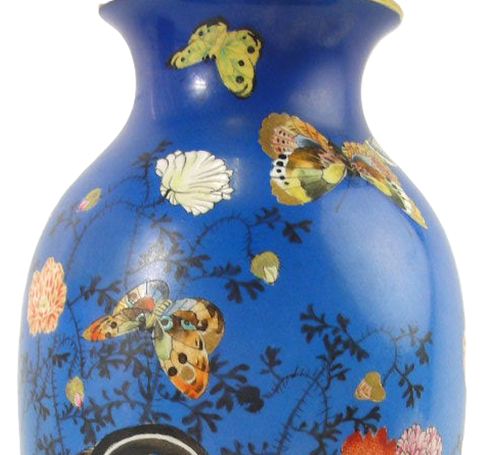

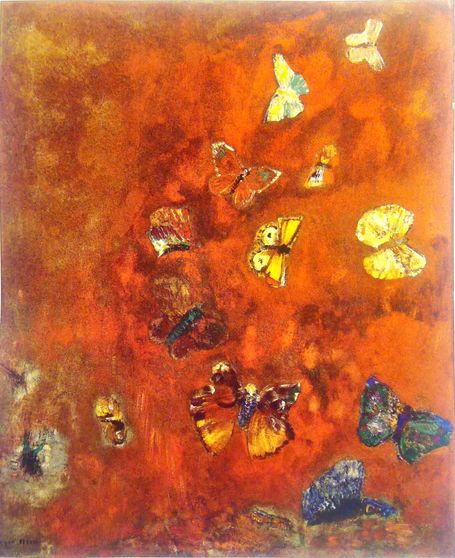

Redon's frequent depictions of flowers and butterflies share much in common with Japanese porcelain compositions of such motifs. A few works by Taizan Yohei, one of the famous Meiji period (1868-1912) ceramicists, are offered for comparison with Redon. That is to say there is another type of ‘Cloisonnisme’ to that of Gauguin (that can be seen in his works too), a Cloisonnisme in a more literal sense than has been usually understood, closely related to the imagery and colors of specifically Japanese export porcelains, a connection that needs to be better addressed.

A closer look below at a section of the butterfly and rooster design vase of Taizan Yohei (the 9th) and Redon's butterfly paintings.

Cloisonne, both of the older, ’doroshippo’ (泥七宝, literally 'muddy' shippo), i.e. using non-glossy/transparent slips (不透明油), and the more polished and shiny cloisonne developed by Kaji Tsunekichi (梶常吉) during the Edo period, both kinds which were exported and avidly collected in Europe, along with Satsuma Kinrande (金襴手) type wares, which were pronounced in their use of gold paints. Below are some comparisons of characteristic pastel type light green-olive colors in Redon's paintings, which also typical of Japanese cloisonne porcelains, as those by Namikawa Yasuyuki (並河靖之) and various other Meiiji period Japanese craftsmen of the latter 19th century.

As listed also on the MOMA website on Odilon Redon, the Wikipedia entry on Odilon Redon does correctly point out that:

“He developed a keen interest in Hindu and Buddhist religion and culture, which increasingly showed in his work. Redon is perhaps best known today for the dreamlike paintings created in the first decade of the 20th century, which were inspired by Japanese art and leaned toward abstraction. His work is considered a precursor to Surrealism.” (MOMA excerpt of the Wikipedia article on Odilon Redon, at moma.org, visited 2024.12.8)

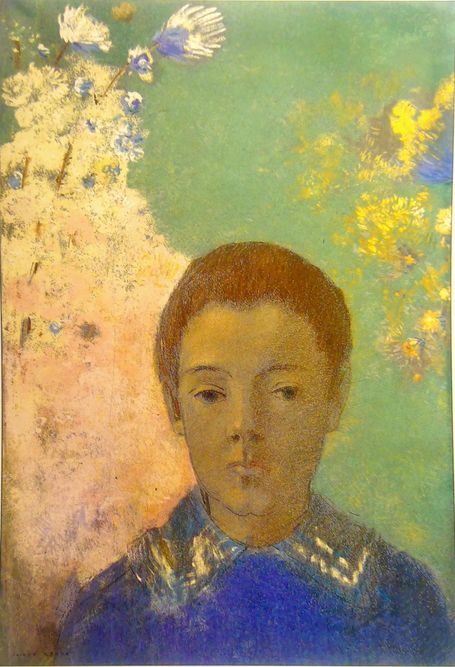

Natalie Adamson speaks of Odilon Redon’s 'search for a lost paradise’ (‘Japonisme and Odilon Redon’s decorative painting, The search for a lost paradise’, Apollo 146, Oct. 1997), where where Japanese decorative arts, such as byobu (e.g. Redon's Paravent d'Olivier Sainsère 1903 at the Gifu Museum of Art), are more of an indirect influence upon a personal formulation of a conception of paradise, but in fact Japanese art, especially religious art, such as illustrated sutras or copies of them, may have literally supplied a vivid representation of 'paradise found.' Kakemono (掛物 hanging scrolls) and makimono (巻物 scrolls such as sutras and emaki) were almost equal in prominence to prints for some collectors as Pierre Barbouteau, for instance (not to mention other numerous European collectors and dealers), whose vast collection went on the market in 1904, at the time when Redon was making his shift to the chromatic qualities found in such type of works.

That impression, of a strong affinity to Japanese decorative techniques of byobu, makimono, porcelain, kimono textiles and other traditional kogei, becomes stronger when one looks at assemblages of Redon's works from a distance, such as the Baron Robert de Domecy’s château (at Domecy-sur-Vault) dining room decorative panels (1900-1901) at the Orsay Museum (see Kitazawa, 2000 or Louvre Abu Dhabi for photos and discussion in relation to japonisme).

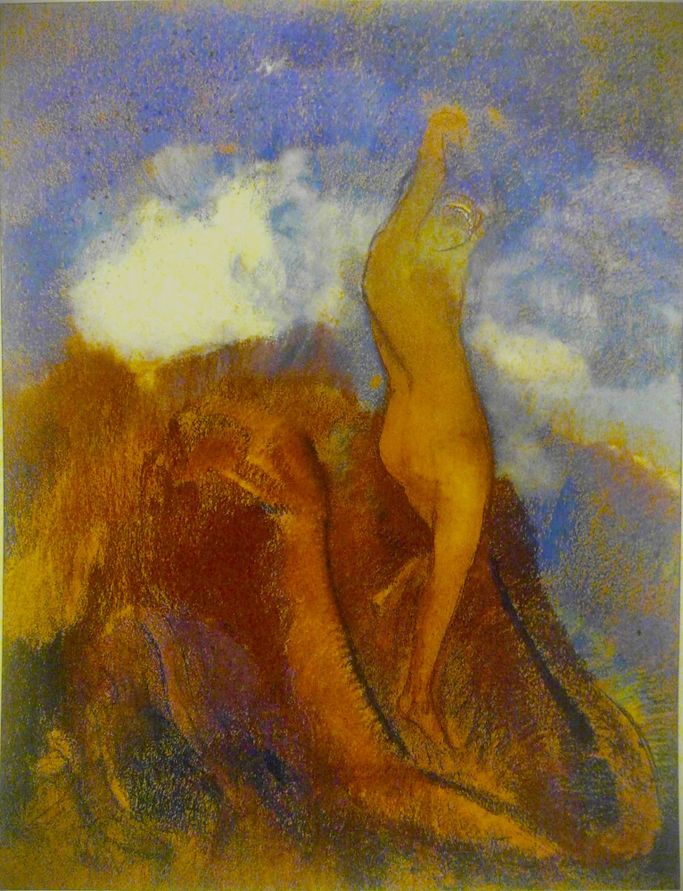

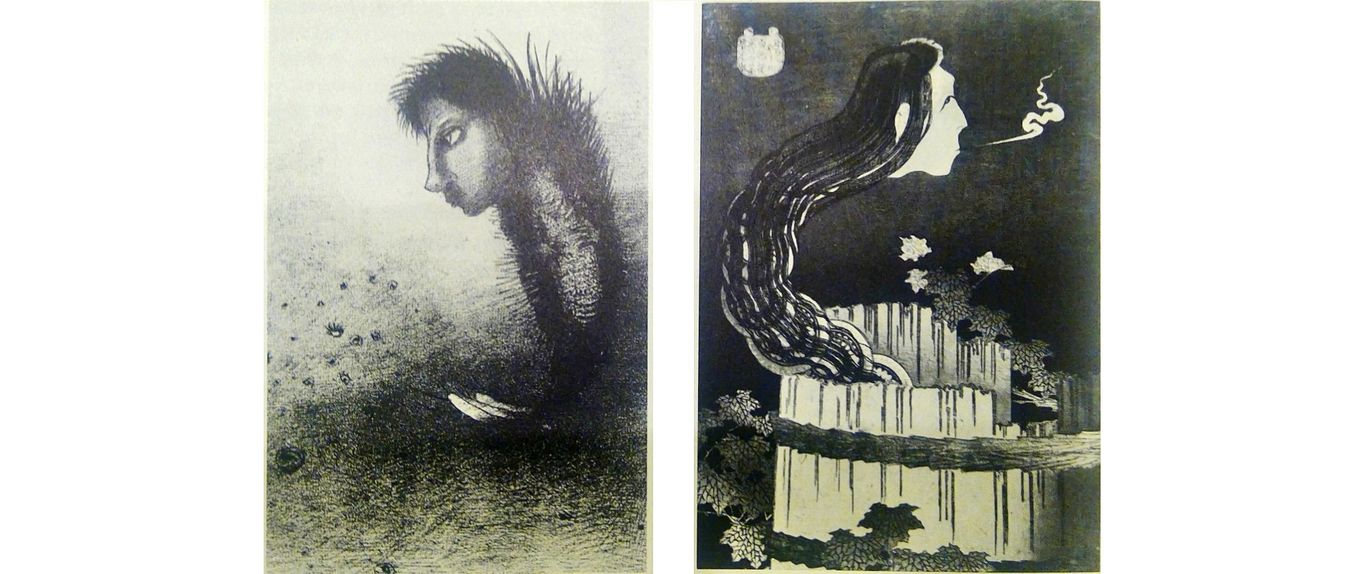

Klaus Berger, the leading authority on Odilon Redon, and author of Japonisme in Western Painting from Whistler to Matisse (1992, Cambridge Studies in the History of Art), speaks of a turning point in Redon’s work, the appearance of pronounced spatial distortion and fragmentation of objects, and asks, where does this come from? The answer, according to Berger, is clearly the influence of Japan, and he provides us with the following juxtaposition of images:

“When we find in subsequent works an ever closer succession of bolder and bolder imaginative creations---dream figures coined with total conviction, logic in illogic---then the source of the artist’s inspiration is no longer in doubt: once more, it is Japan. Compare Then There Appears a Singular Being… of 1888 [121], with Hokusai’s woodcut The Spirit of Sarayashiki, 1830 [122].” (Berger, 1992, p. 171)

121 Odilon Redon. Then There Appears a Singular Being with a Man’s Head on a Fish’s Body, 1888. 122 Katsushika Hokusai. The Spirit of Sarayashiki, 1830.

Berger, speaking of caricature having its source in the fantastic, which leads in turn to distorting and exaggerating the defining detail, and the transposing of the natural into the supernatural, while tolerated as a minor art in the West, required the Japanese impetus to allow it to become a force in serious artistic expression:

“A print by Hokusai, such as the one shown in plate 122, opened up a new dimension: it came as a messenger from a less disenchanted, less industrialized world, and evoked a grand, spontaneous frisson that the West could not achieve.” (p.171-172) … “It is no wonder that Redon kept as close to the daemonic ‘reality’ of the [Hokusai] image as ever he could. His Japonisme sprang from the object, and not, as with other artists, from a concern with a new conception of space, or with the ready-made anti-illusionism of the ‘archaic’. … On the one hand, the decorative principle rooted in the artistic innovations of Seurat and Gauguin found a continuation in the ‘painterly’ art of Fauvism; on the other, the expressive intensity of Redon’s drawings showed the way to Expressionism and Surrealism. Both tendencies drew nourishment from the Japanese woodcut, but what they took from it differed, and was differently seen.” (p. 172)

Here Berger gives pre-eminence to the ukiyo-e woodblock print, but that was but one of many sources of inspiration for Redon, of which Japanese decorative crafts as cloisonne pottery and books/scrolls were, as we have discussed above, also equally important in the finished product, the package of defining imagery and aesthetic qualities that was recognizably 'Redon-esque', and the following are perhaps a more telling juxtaposition of images than those offered by Berger.

Bibliography

Adamson, Natalie A. ‘Japonisme and Odilon Redon’s decorative painting, The search for a lost paradise’, Apollo 146, Oct. 1997.

Berger, Klaus. Japonisme in Western Painting from Whistler to Matisse (Cambridge Studies in the History of Art). Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Kitazawa Chikashi (喜多崎親). 'Correspondence between Figure and Background: Ametaphorical structure of Symbolist painting in Odilon Redon’s Portrait of Mme. Robert de Domecy' (呼び交わす人物と背景: オデイロン・ルドンの《口べ一ル・ド・ドムシー男爵夫人の肖像》に見る 象徴主義絵画の隠喩的構造), 2000. 国立西洋美術館出版物リポジトリ, https://nmwa.repo.nii.ac.jp.

Louvre Abu Dhabi. 'Japanese Connections: The Birth of Modern of Modern Decor' (section on Odilon Redon). In conjunction with the 2018 exhibition with the same title, curated by Isabelle Cahn, Chief Curator of Paintings, Orsay Museum. At https://www.louvreabudhabi.ae.

MOMA (Museum of Modern Art) Official website, 'art and artists': Odilon Redon French, 1840–1916 at moma.org (visited 2024.12.11).