Nordic Japonisme from Aalto to Utzon

Alvar Aalto (1898-1976)

"Away at the other end of the table sits Hokusai, smiling..."

Alvar Aalto, 'Benvenuto's Christmas Punch' (Keberos, No. 1-2, 1921)

In one of his essays, Alvar Aalto, the renown Finnish architect, has concocted an imaginary Christmas party as part of a dream. Hosted by Benvenuto Cellini, the great Renaissance sculptor, Aalto, calling himself 'Ping', sits at the end of a long table with the leading artistic and philosophical luminaries of past ages, lined on both sides before him.

Near him are the architects Bramante and Le Notre, and a little further away the architect of the great Egyptian pyramids, a talking mummy. There are countless others: "profiles, profiles, profiles, all representing one brain." The hall is in a great din with their heated philosophizing.

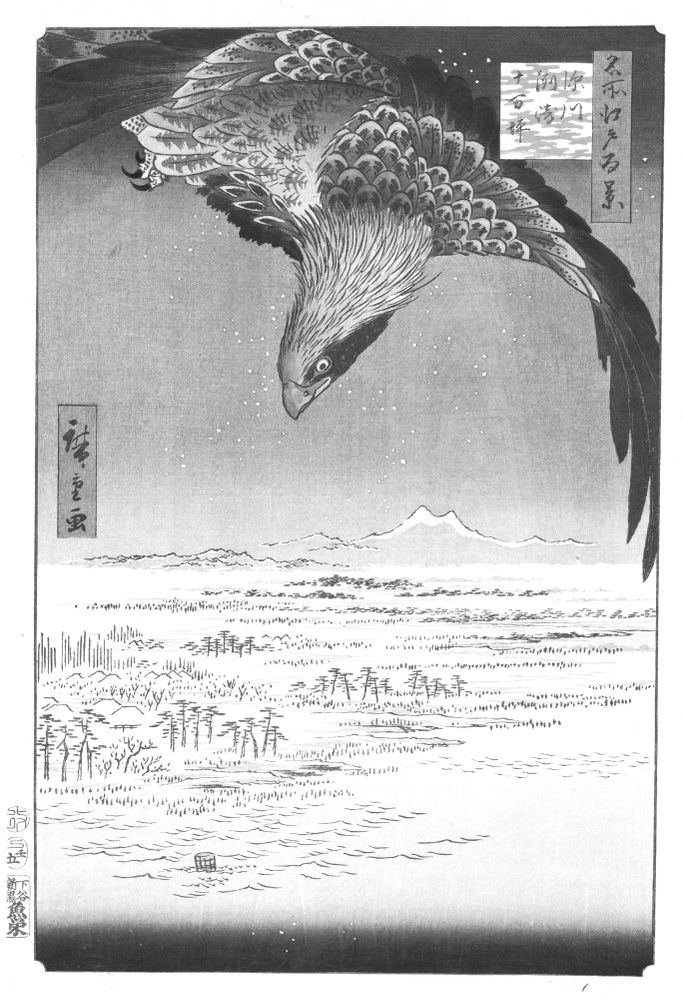

Among them, at the far end of the table, thereby facing him, quietly sits the ukiyo-e master Katsushika Hokusai. Thus Hokusai, it seems, symbolizes the Japanese artistic genius. He is furthest from Aalto, yet clearest in view; and in this dream world of Alto, he is no doubt, a key part of that "one brain" of civilization.

The Walls of Alvar Aalto

A Japanese Sense of Repetition, A Japanese Sense of Collage

Uploaded 2023.4.27

A handout from a series of lectures on architectural japonisme, Kyoto University,

and p. 2 of Architectural Juxtapositions, 2016, unpublished, by Yasutaka Aoyama

Aalto's Japanese Sense of Repetition / Uniformity

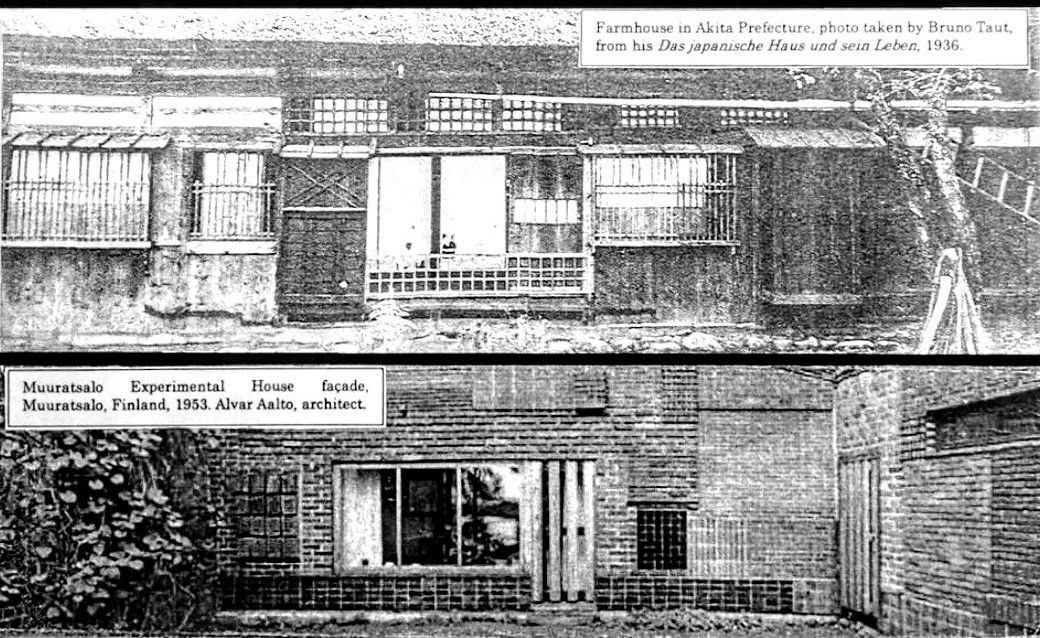

Note the striking resemblance between Edo period facades and those of Aalto's shown below, each with long stretches of simple, unadorned vertical lines. Aalto, in his Seinajoki library design, even follows the Owari daimyo yashiki's (typical of the times) uninterrupted uniformity of the of the prominent upper row of vertical lines, in combination with a second, lower row of demarcated sets of similar but shorter lines (and we might add he is also going along with a revival of this type of facade emphasizing close-spaced, vertical lines in post-WWII modern Japanese architecture, e.g. Matsumura Masatsune's 松村正恒 Hizuchi Elementary School 日土小学校, first building completed 1956, addition completed 1958, in Yawatahama City, Ehime Prefecture).

Aalto's Japanese Sense of 3-D Collage / Montage

Note the surprising number of correspondences of detail, relative positioning, and sequencing between the Japanese farmhouse in the middle photo below with that of Aalto's walls at his Muuratsalo House, placed for comparison above and below it. Spending some time looking at the Muuratsalo walls together with the Japanese farmhouse facade offers an number of surprises for the careful observer.

Aalto's Japanese Sense of Materials and Textures

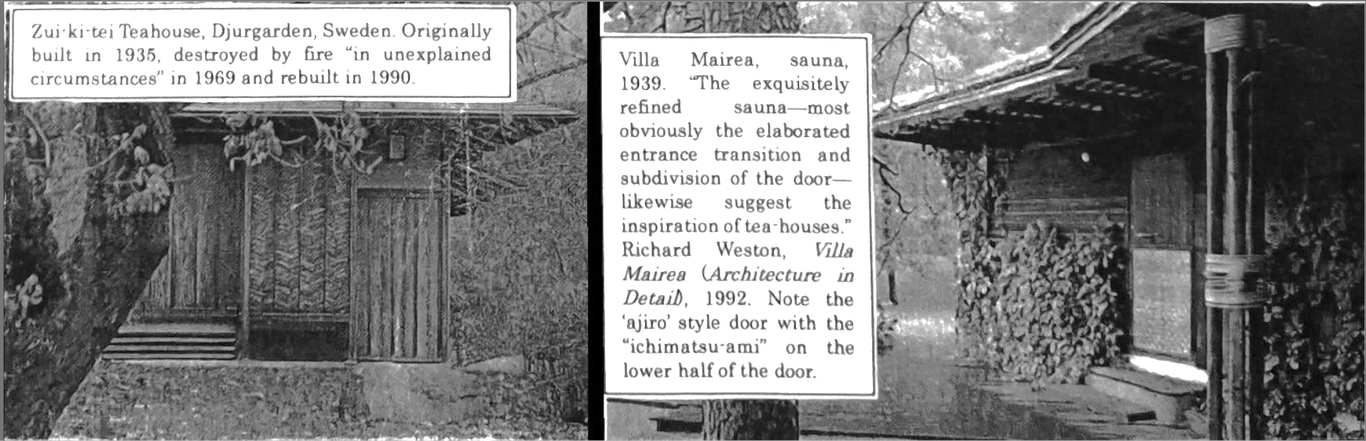

Japanese teahouse architecture in Scandanavia and Alvar Aalto's sauna at his famous Villa Mairea.

Alvar Aalto's Villa Mairea

Finland and Japan Merging with Surprising Ease

(Kyoto Univ. lecture handout, 2015.12.20 and in Architectural Juxtapositions, 2016, p.3)

Yasutaka Aoyama

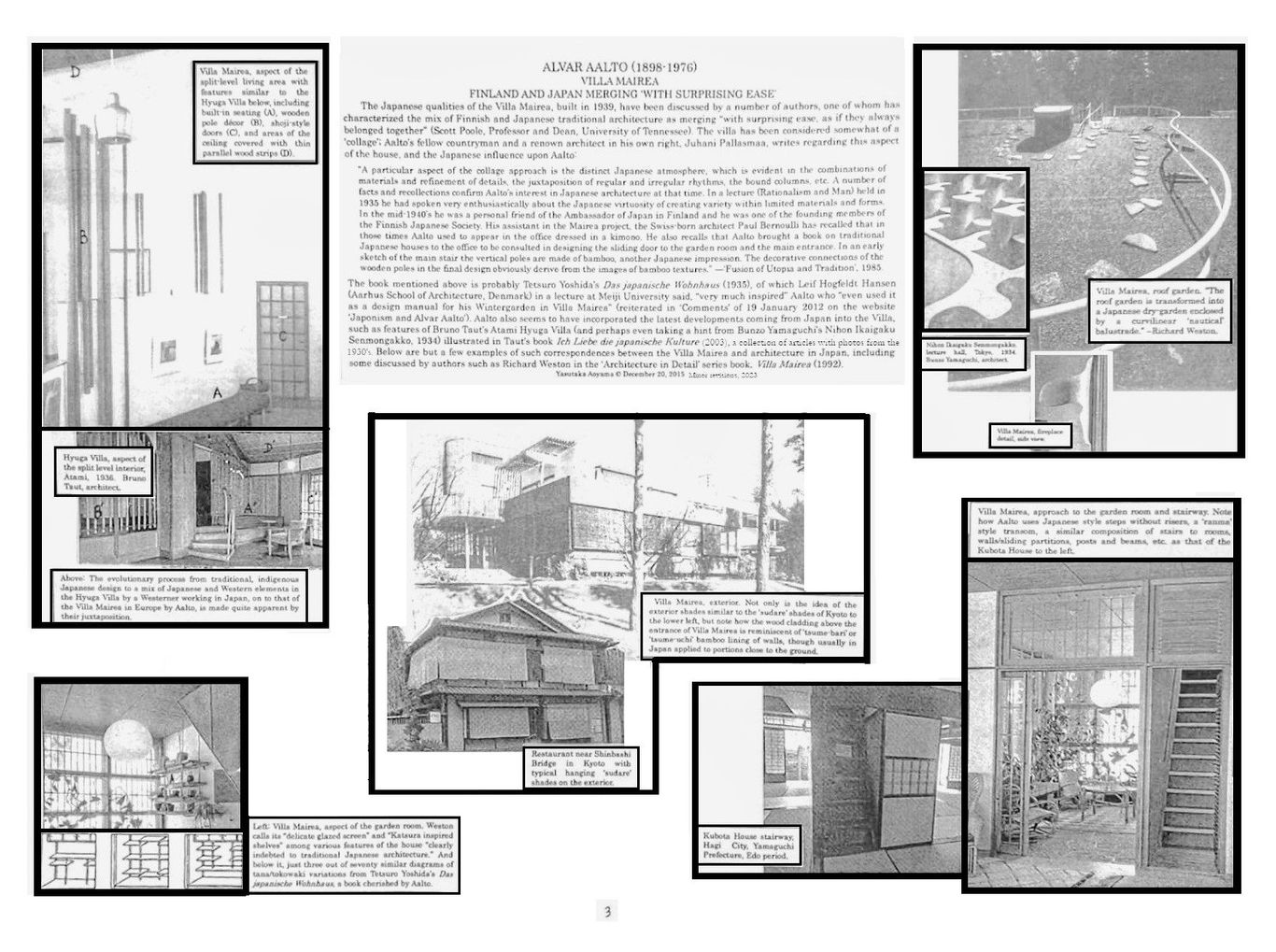

The Japanese qualities of the Villa Mairea, built in 1939, have been discussed by a number of authors, one of whom has characterized the mix of Finnish and Japanese traditional architecture as merging "with surprising ease, as if they always belonged together" (Scott Poole, Professor and Dean, University of Tennessee). The villa has been considered somewhat of a 'collage'; Aalto's fellow countryman and a renown architect in his own right, Juhani Pallasmaa, writes regarding this aspect of the house, and the Japanese influence upon Aalto:

"A particular aspect of the collage approach is the distinct Japanese atmosphere, which is evident in the combination of materials and refinement of details, the juxtaposition of regular and irregular rhythms, the bound columns, etc. A number of facts and recollections confirm Aalto's interest in Japanese architecture at that time. In a lecture (Rationalism and Man) held in 1935 he had spoken very enthusiastically about the Japanese virtuosity of creating variety within limited materials and forms. In the mid-1940's he was a personal friend of the Ambassador of Japan in Finland and he was one of the founding members of the Finnish Japanese Society. His assistant in the Mairea project, the Swiss-born architect Paul Bernoulli has recalled that in those times Aalto used to appear in the office dressed in a kimono. He also recalls that Aalto brought a book on traditional Japanese houses to the office to be consulted in designing the sliding door to the garden room and the main entrance. In an early sketch of the main stair the vertical poles are made of bamboo, another Japanese impression. The decorative connections of the wooden poles in the final design obviously derive from the images of bamboo textures." ---'Fusion of Utopia and Tradition', 1985.

The book mentioned above is probably Tetsuro Yoshida's Das japanische Wohnhaus (1935), of which Leif Hogfeldt Hansen (Aarhus School of Architecture, Denmark) in a lecture at Meiji University said, "very much inspired" Aalto who "even used it as a design manual for his Wintergarden in Villa Mairea" (reiterated in 'Comments' of 19 January 2012 on the website 'Japonism and Alvar Aalto'). Aalto also seems to have incorporated the latest developments coming from Japan into the Villa, such as features of Bruno Taut's Atami Hyuga Villa (and perhaps even taking a hint from Bunzo Yamaguchi's Nihon Ikaigaku Senmongakko, 1934) illustrated in Taut's book Ich Liebe die japanische Kultur (2003), a collection of articles with photos from the 1930's. Below are but a few examples of such correspondences between Villa Mairea and architecture in Japan, including some discussed by authors such as Richard Weston in the 'Architecture in Detail' series book, Villa Mairea (1992).

The text below has been reiterated above for the sake of better legibility.

Alvar Aalto's Saynatsalo Town Hall

And the Topology of Japanese Fortifications

(Lecture handout, 2015.12.20 and in Architectural Juxtapositions, 2016, p.4)

Yasutaka Aoyama

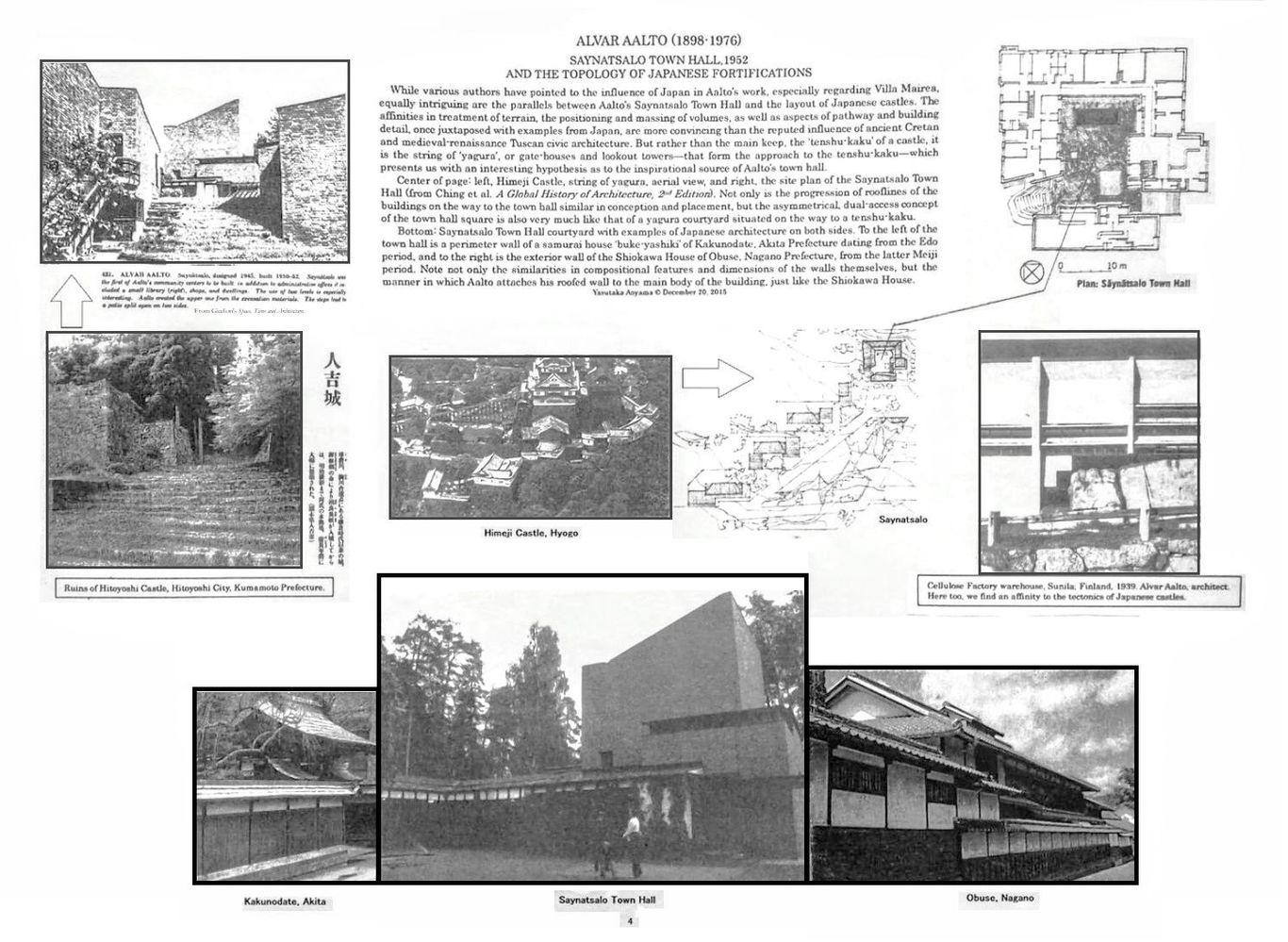

While various authors have pointed to the influence of Japan in Aalto's work, especially regarding Villa Mairea, equally intriguing are the parallels between Aalto's Saynatsalo Town Hall and the layout of Japanese castles. The affinities in treatment of terrain, the positioning and massing of volumes, as well as aspects of pathway and building detail, once juxtaposed with examples from Japan, are more convincing than the reputed influence of ancient Cretan and medieval-renaissance Tuscan civic architecture. But rather than the main keep, that is the 'tenshu-kaku' of a Japanese castle, it is the string of 'yagura' or gate-houses and lookout towers---that form the apporach to the tenshu-kaku---which presents us with an interesting hypothesis as to the inspirational source of Aalto's town hall.

Center of page, left: Himeji Castle, aerial view of a string of yagura; and right, the site plan of the Saynatsalo Town Hall (from Ching et al. A Global History of Architecture, 2nd Edition). Not only is the progression of rooflines of the buildings on the way to the town hall similar in conception and placement, but the asymmetrical, dual-access concept of the town hall square is also very much like that of a yagura courtyard situated on the way to a tenshu-kaku.

Bottom: Saynatsalo Town Hall courtyard with examples of Japanese architecture on both sides. To the left of the town hall is a perimeter wall of a samurai house 'buke-yashiki' of Kakunodate, Akita Prefecture, dating from the Edo Period. To the right is the exterior wall of the Shiokawa House of Obuse, Nagano Prefecture, from the latter Meiji Period. Note not only the similarities in compostional features and dimensions of the walls themselves, but the manner in which Aalto attaches his roofed wall to the main body of the building, just like the Shiokawa House. The two Japanese walls have been placed right against that of Aalto's, so that one can see how they almost blend into one another, so similar that they are.

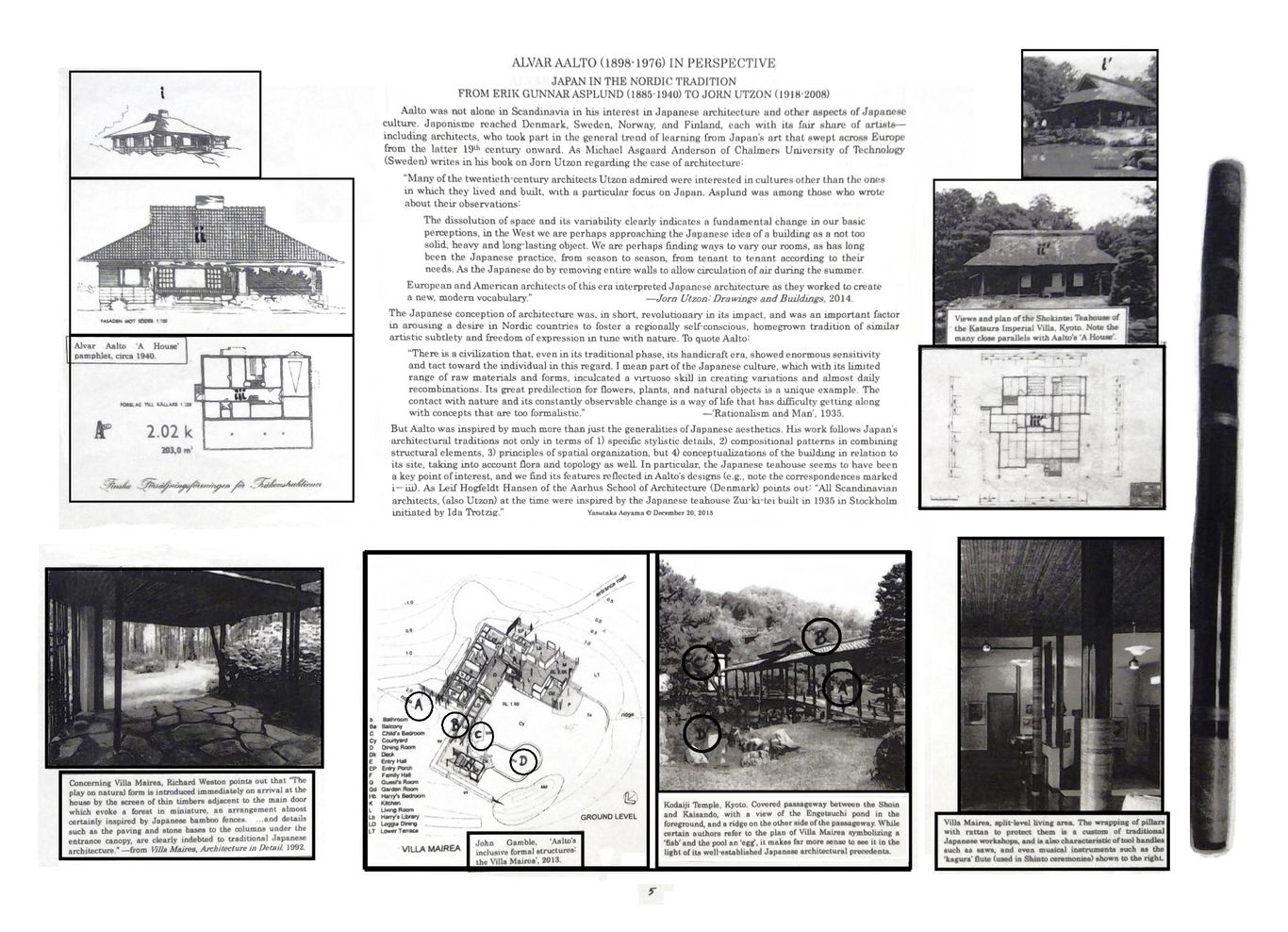

Alvar Aalto in Perspective

Japan in the Nordic Tradition

From Eric Gunnar Asplund to Jørn Utzon

Lecture handout, 2015.12.20 and in Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 5

Yasutaka Aoyama

Aalto was not alone in Scandinavia in his interest in Japanese architecture along with other aspects of Japanese culture. Japonisme reached Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Finland, each with its fair share of artists, including architects, who took part in the general trend of learning from Japan's art that swept across Europe from the latter 19th century onward. As Michael Aagaard Anderson of Chalmers University of Technology (Sweden) writes in his book on Jorn Utzon regarding the case of architecture:

"Many of the twentieth-century architects Utzon admired were interested in cultures other than the ones in which they lived and built, with a particular focus on Japan. Asplund was among those who wrote about their observations:

'The dissolution of space and its variability clearly indicates a fundamental change in our basic perceptions; in the West we are perhaps approaching the Japanese idea of a buiding as a not too solid, heavy and long-lasting object. We are perhaps finding ways to vary our rooms, as has long been the Japanese practice, from season to season, from tenant to tenant according to their needs. As the Japanese do by removing entire walls to allow circulation of air during the summer.'

European and American architects of this era interpreted Japanese architecture as they worked to create a modern vocabulary."

Jorn Utzon, Drawings and Buildings, 2014.

The Japanese conception of architecture was, in short, revolutionary in its impact, and an important factor in arousing a desire in Nordic countries to foster a regionally self conscious, homegrown tradition of similar artistic subtlety and freedom of expression in tune with nature. To quote Aalto:

"There is a civilization that, even in its traditional phase, its handicraft era, showed enormous sensitivity and tact toward the individual in this regard. I mean part of the Japanese culture, which with its limited range of raw materials and forms, inculcated a virtuoso skill in creating variations and almost daily re-combinations. Its great predilection for flowers, plants, and natural objects is a unique example. The contact with nature and its constantly observable change is a way of life that has difficulty getting along with concepts that are too formalistic.” ‘Rationalism and Man', 1935.

But Aalto was inspired by much more than just the generalities of Japanese aesthetics. His work follows Japan's architectural traditions not only in terms of 1) specific stylistic details, 2) compositional patterns in combining structural elements, 3) principles of spatial organization, but 4) conceptualizations of the building in relation to its site, taking into account flora and topology as well. In particular, the Japanese teahouse seems to have been a key point of interest, and we find its features reflected in Aalto's designs (e.g., note the correspondences marked i-iii). As Leif Hogfeldt Hansen of the Aarhus School of Architecture (Denmark) points out: “All Scandinavian architects, (also Utzon) at the time were inspired by the Japanese teahouse Zui-ki-tei built in 1935 in Stockholm initiated by Ida Trotzig.”

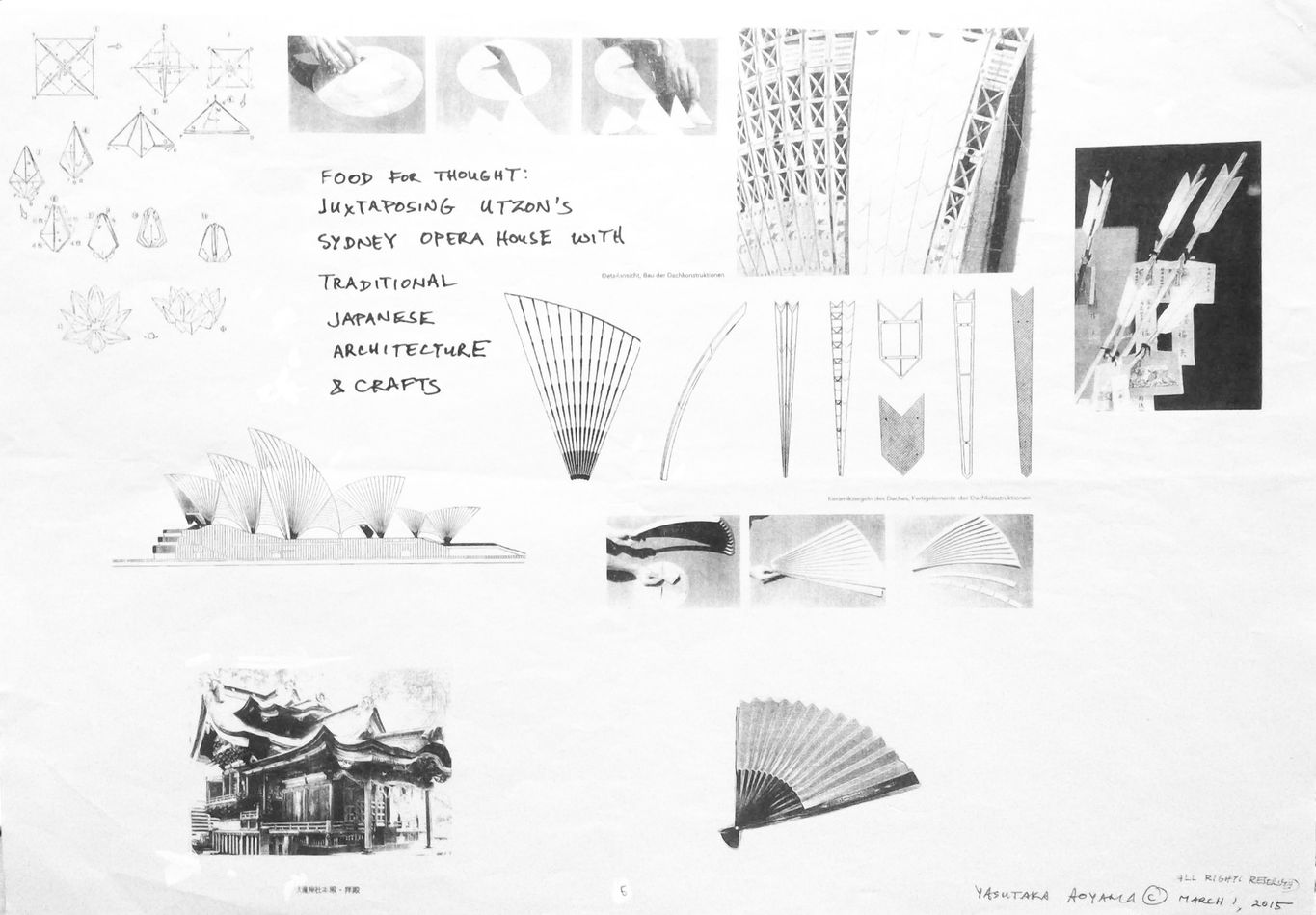

Juxtaposing Jorn Utzon's Sydney Opera House

with Japanese Architecture and Crafts

Lecture handout 2015.3.1 and in Architectural Juxtapositions, 2016, p. 6

Yasutaka Aoyama

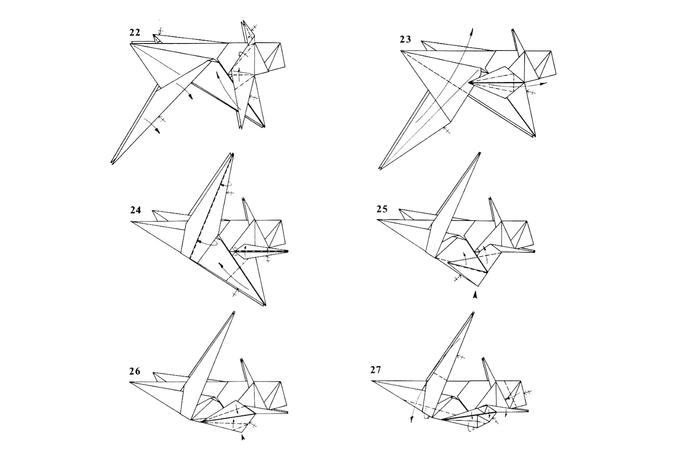

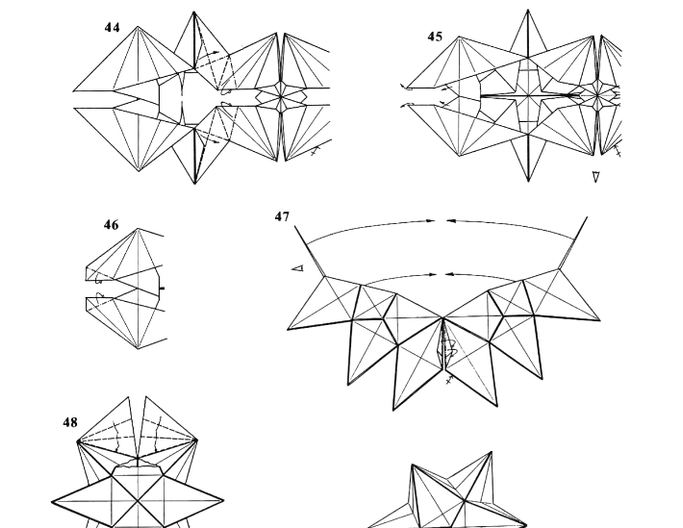

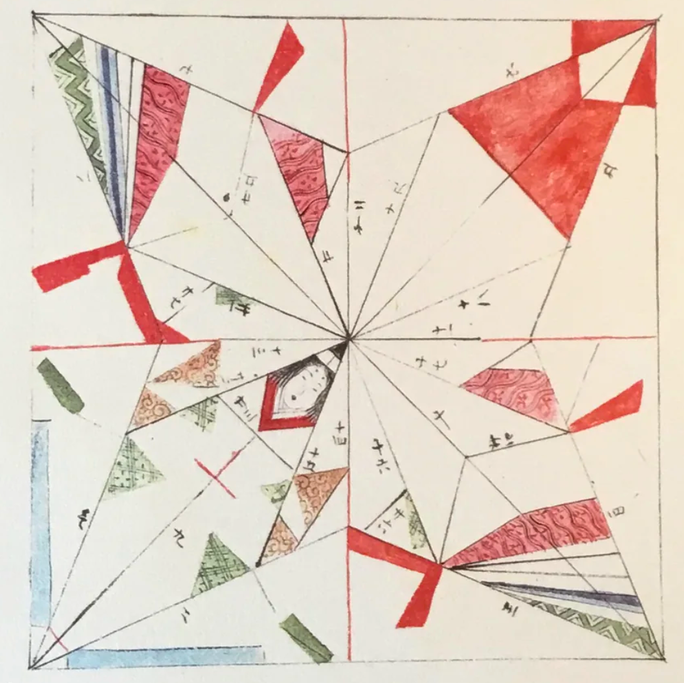

Counterclockwise, from upper left:

Origami and Utzon's parti creation and mental approach,

Opera House roof design and layered Japanese shrine roof design,

Opera building frame structure and a Japanese folding fan,

Opera House details and Japanese shrine displays of arrows of good fortune.

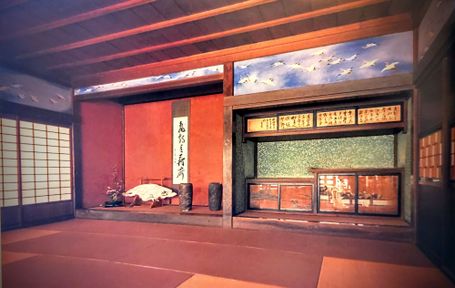

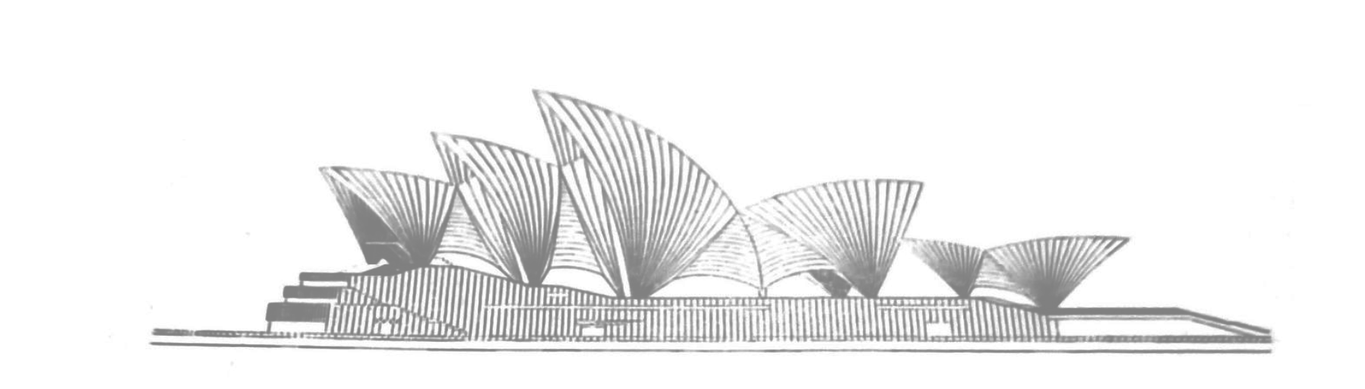

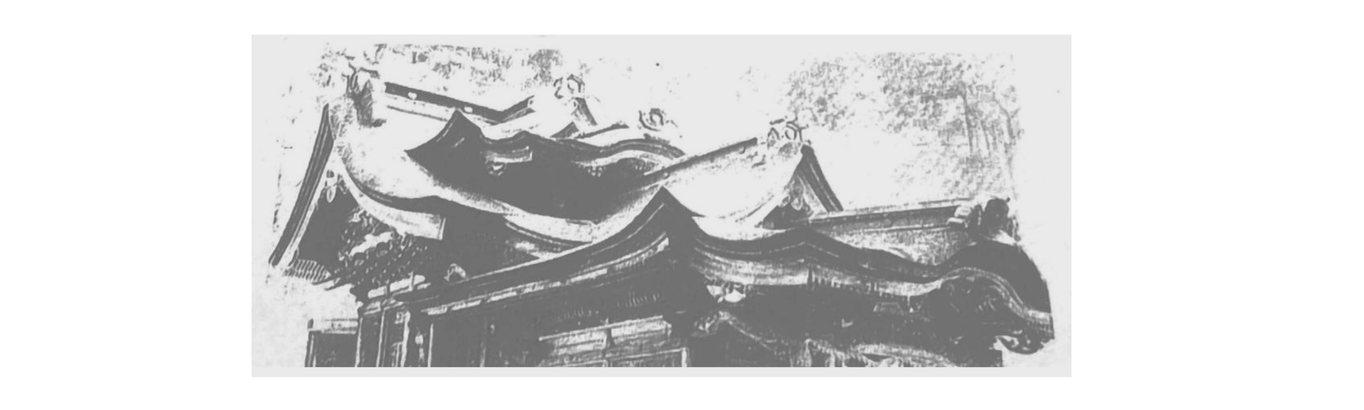

Sydney Opera House elevation compared with the roofline of Otaki Shrine (1843), Echizen, Fukui Prefecture

The structures above remind us of Jorn Utzon's sketch of a Japanese temple (from Sigfried Giedion's Space, Time and Architecture). As Giedion says, Utzon has drawn only the roof and platform. The roof floats in mid-air, or rather it becomes the entire structure, as in his Sydney Opera house. One may also be reminded of seeing a Noh stage, comprised only of an open platform and roof, where the pillars to support it are kept to a minimum so as not to obstruct visibility.

But in fact this idea of Japanese architecture as all roof floating on a platform, the idea of the roof being the primary focus of attention, the entity of psychological primacy, its essence and existence, was grasped upon and actualized before Utzon by Tange Kenzo (with the sculptor Isamu Noguchi) in his Hiroshima Peace Memorial monument complex, designed in 1949.

Clearly the shape of this monument, shown below, which sits on a platform on water, is one with deep prehistoric roots, already a well established architectural form even before the 'iegata' house type haniwa pottery (shown below to the left) of the 3rd to 5th centuries; it was already engraved in earlier large bronze 'dotaku' bells from the pre-Christian era (and perhaps traces its origins to the islands of Southeast Asia, in similar roofed houses found, for instance, in the Celebes island of Indonesia).

We can see this idea, however modified and multiplied, has been utilized by Utzon in his Sydney Opera House. It retains the basic concept of a roof with eaves shooting out at both ends, placed on a extended platform floating on water, as was shown by Tange at Hiroshima, and which in turn, owes its unconscious resonance with the Japanese people due to its archetypal ancestor, and which has continued in one form or the other through the centuries as in the tea house roof to the right.

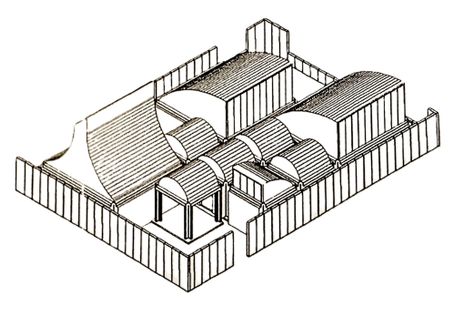

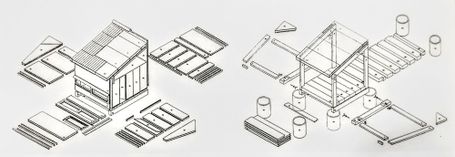

Herning School Complex

These rounded, and often convoluted, rolling or intersecting roof forms of Japan, which dominate the building, comprising the majority of the surface area of the structure, are reflected in Utzon's other celebrated works, not only his Sydney Opera House. His prototype for the Herning School Complex (1967-1970's, uncompleted and converted into a single family home in 2002), with its roofs of varying heights and shapes, remind one of Japanese Buddhist temple compounds usually with one extremely high, steep, pitched 'hondo' (main hall) roof, surrounded by smaller, lower roofed structures, such as a 'shoro' bell tower or the monks' living quarters. (Photos by Per Nagel, in Jorn Utzon Houses by Henrik Sten Moller & Vibe Udsen, Copenhagen: Living Architecture, 2004.)

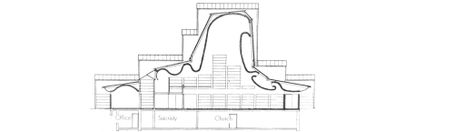

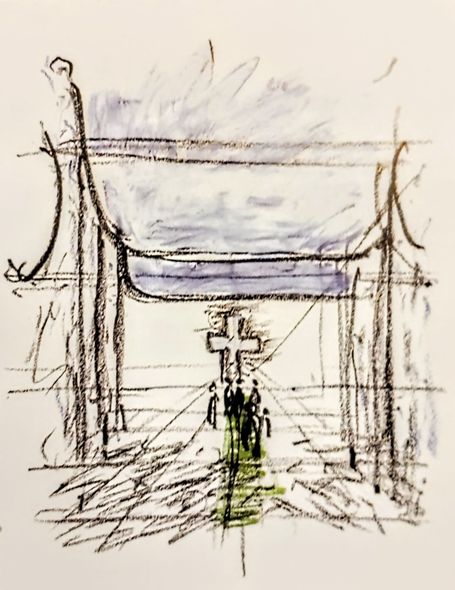

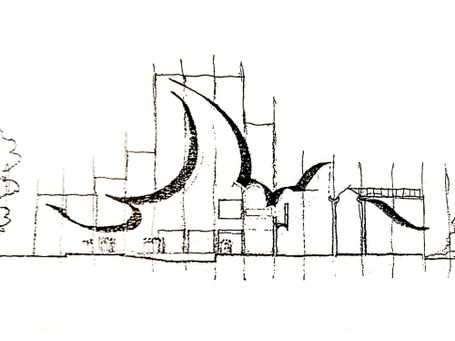

Bagsvaerd Church

In the case of his Bagsvaerd church north of Copenhagen (1976), his croquis sketches, once again, show an East Asian-type roof without walls and a cross under it, mixing Buddhist and Christian forms. However, in this case, the overhead 'wave' like structure is covered over with a more rectangular, simple (a somewhat late Meiji to early Showa style looking) facade and roof. Throughout the church various Japanese interior architectural forms from shoji doors to kumiko screens (parquetry-like but open fretwork) are employed together with an overall Japanese traditional aesthetic---cleanliness, simplicity, 'shibui' color tones and restraint, and a calming sense of 'ochitsuki'.

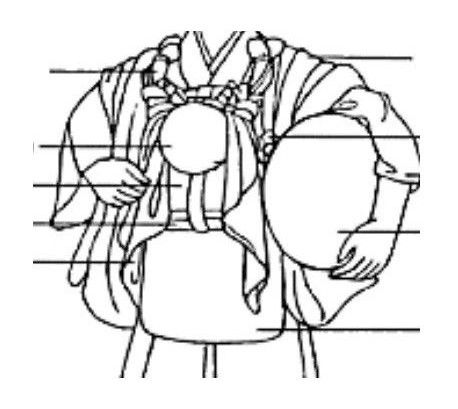

Various aspects of the Bagsvaerd Church, sketches, interiors and exteriors. Even the clothing of the architectural team in the photo above upper right corner is reminiscent of Japanese happi or yukata.

Below an early sketch of Utzon's for the church sandwiched between some roofs styles in Japan. It is important to re-emphasize that large convoluted roof shapes, reminiscent of waves, mountains, or other forms combined, and which overwhelmingly dominate the surface area and volumes of the structure, was a pecularity of Japan and not necessarily a characteristic of continental Asia. Its closest cousins are the roofs found in the Indonesian isles; but even those elegant and impressive forms do not have the intermixing shapes and intersecting lines that are found throughout the Japanese isles.

As mentioned above, the wave-like ceiling structure of the church is entirely covered over with simple open or shed gabled roofs with shallow eaves, and a flat wall surface with clearly outlined segments, and generally marked by a more 'cubical' construction, which is akin to a style in the late nineteenth early twentieth century seen in Japan. These were somewhat 'Westernized' exteriors, though fundamentally based on much older traditional facades; as that in the photo below right of Teramachi Street in Morioka City, Iwate prefecture, whose basic appearance dates to the 18th century.

Biographers of Utzon have pointed to the Stoclet Palace of Hoffman for instance, or the Middle East, as sources of inspiration; there may be aspects of those designs in his work, as the fretwork screens which are similar to windows found in the Middle East and Mughal India. There are also parallels with Arata Isozaki's work, at around the same time. Certainly he has reworked things in his own way so that it is not completely one thing or another. Yet for the most part, the various aspects of his architecture are those typical of Japan, and are often used in combinations as found in Japan, though there are of course plentiful exceptions.

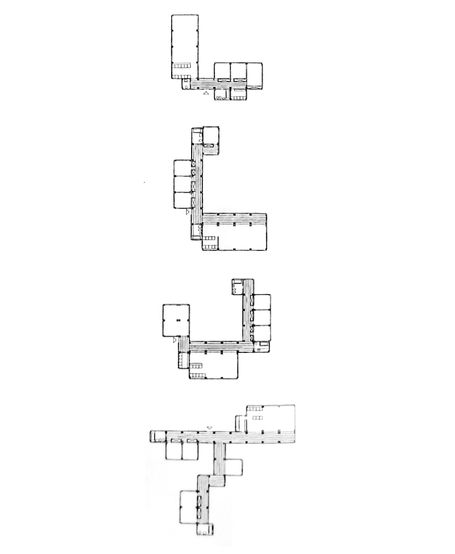

Not only specific forms, but many of the aesthetic principles and ideas that characterize his work can be called Japanese. It is said Utzon got to know the Ying-tsao Fa Shih, the ancient Chinese architectual manual, and according to one biographer, "he never ceased to come back to it." Yet surely, though it "describes a system of standardised elements enabling any building to be constructed on the basis of a single topology" that emphatic lesson was gained from seeing it live in action when he went in Japan, and entered any house that was built according to standardized tatami mat units and shoji panel sizes.

Furthermore, regarding not only standardization but repetitive effects, "when he visited the temples at Kyoto and Nara in Japan, what struck him about their alleys of torii was the pleasing effect produced by the conjunction of these line-ups of identical portals, all the same colour, with the vagaries of the topolography." (Michael Juul Holm, et. al, Jorn Utzon: The Architect's Universe, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, 2004, p.78) But surely that is not all. His ideas about "additive architecture" is certainly in tune with the above, and many of his ideas converge with key principles of Japanese aethetics.

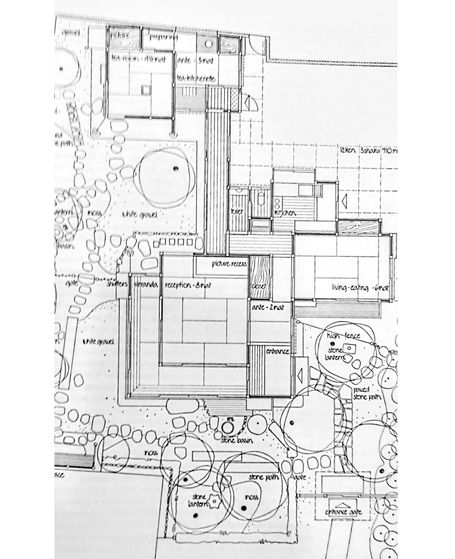

Espansiva

Just as Utzon's religious architecture has much in common with Japanese religious architecture, so his residential architecture, such as his Espansiva (1969) project, like the house he designed for himself at Hellebaek, Denmark, has much in common with traditional Japanese residential architecture, as well as with teahouse design.

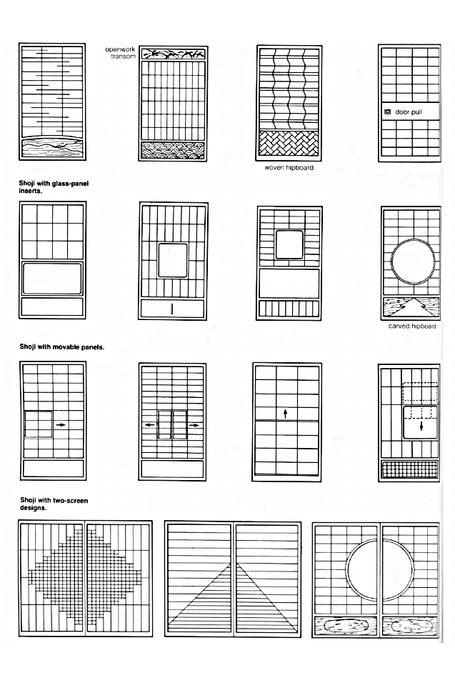

For comparison, a typical Japanese late Edo to early Showa house plan is shown below, center, from Heinrich Engel's The Japanese House: A Tradition for Contemporary Architecture (Tokyo: Tuttle, 1964), which, along with Tetsuro Yoshida's book on Japanese architecture, The Japanese House and Garden (English version,1955), Utzon may have read, as many of his drawings and ideas parallel those in these books (the other photos and diagrams are from Henrik Sten Moller & Vibe Udsen, 2004). Note how the floor level (in the photo below upper left) is raised slightly above ground by short pillars, with the space under the house thus visible, as is the case in traditional Japanese houses. The photo immediately below it (by Per Nagel) of an inner courtyard is reminiscent of a Japanese nakaniwa; the texturing / matting of the patio floor evokes a sand raked rock garden. Though not visible in the photograph, Utzon also has single room separate roofed structures in such enclosures, which remind one of small residential garden teahouses in Japan.

Excerpt on the influence of Japanese architecture upon Utzon and other Scandanavian architects from

Michael Asgaard Andersen's Jørn Utzon: Drawings and Buildings (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2014)

'Many of the twentieth-century architects Utzon admired were interested in cultures other than the ones in which they lived and built, with a particular focus on Japan. ... European and American architects of this era interpreted Japanese architecture as they worked to create a new, modern vocabulary. On the significance of traditional Japanese architecture to contemporary Western efforts, Frank Lloyd Wright writes, "The modern process of standardizing...was in Japan known and practiced with artistic perfection by freedom of choice many centuries ago... The shape of all the houses was determined by the size and shape of assembled mats." The tatami mat was one of several Japanese elements that Western architects referenced in their work with industrialized construction. As Wright's quote documents, the standardized mat was seen as both determinative and liberating, its fixed size presenting options of number and combination. Twentieth-century architects like Wright and Asplund imagined that prefabricated elements would give them a corresponding freedom of choice. In his article "Platforms and Plateaus: Ideas of a Danish Architect," Utzon also remarked on the movable units of Japanese architecture and the effect of the mats: "A refined addition to the expression of the platform in the Japanese house is the horizontal emphasis provided by the movements of the sliding doors and screens, while the black pattern made by the edges of the floor mats accentuates the surface." Utzon became acquainted with Far Eastern architecture early on through his uncle, sculptor Einar Utzon-Frank, and his university professor, architect Steen Eiler Rasmussen, as well as through books by Osvald Sirén and Johannes Prip-Møller. In addition, Utzon met Arne Korsmo while working at Paul Hedquvist's studio during World War II, and together they saw Japanese architecture firsthand at Stockholm's Museum of Ethnography, where the Zui-Ki-Tei teahouse had been assembled. Dovetailing with Wright's coupling of traditional Japanese architecture and standardization, Korsmo, Utzon, and the other members of PAGON advocated looking "to Japan which with its highly developed standardization nevertheless displays an extraordinary variety. The Japanese managed to produce a flexible form of housing in favour of which we now must make a dedicated effort to liberate ourselves." Variation and flexibility were key elements of PAGON's efforts to create new forms of housing, and Korsmo and Utzon tested out possibilities through a number of competition projects for big housing developments. Their designs have a sketch-like nature and because they never won, they never carried their ideas out together. Utzon's own house in Hellebaek---which he designed during the same period---and many of his following projects were clearly inspired by Japanese architecture and Western interpretations thereof.' (pp. 114-116)

For further reading on Utzon and Japan, see 'Yuzo Mikami: The unsung hero behind the Sydney Opera House' by Tomoko Otake (The Japan Times, Dec 27, 2023) and Yuzo Mikami's book translated into English: Utzon’s Sphere: Sydney Opera House — How It Was Designed and Built.

________________________

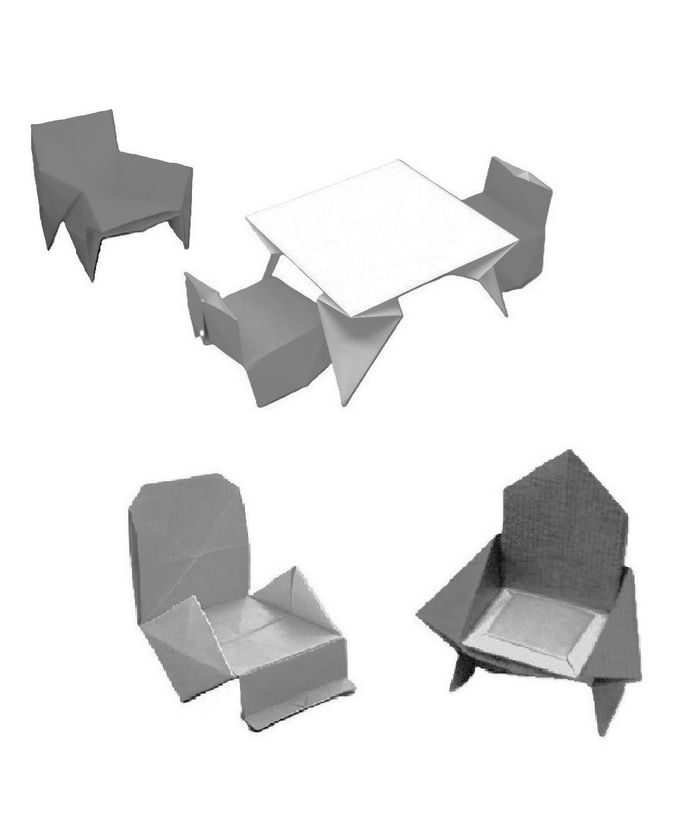

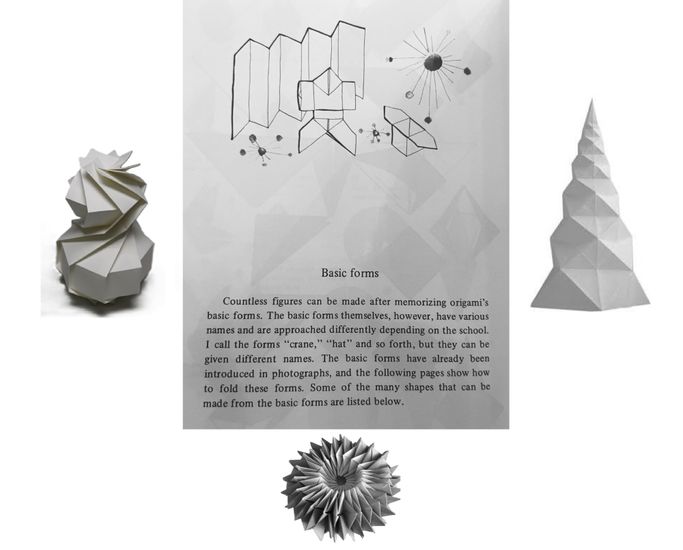

Origami and Architecture

Lecture handout 2015.3.1, Architectural Juxtapositions, 2016 p. 7; Wright added 2024.5.29 and 30; Le Corbusier 2024.6.4, from notes; Eames and Woo/Guerin added 2024.6.15

Yasutaka Aoyama

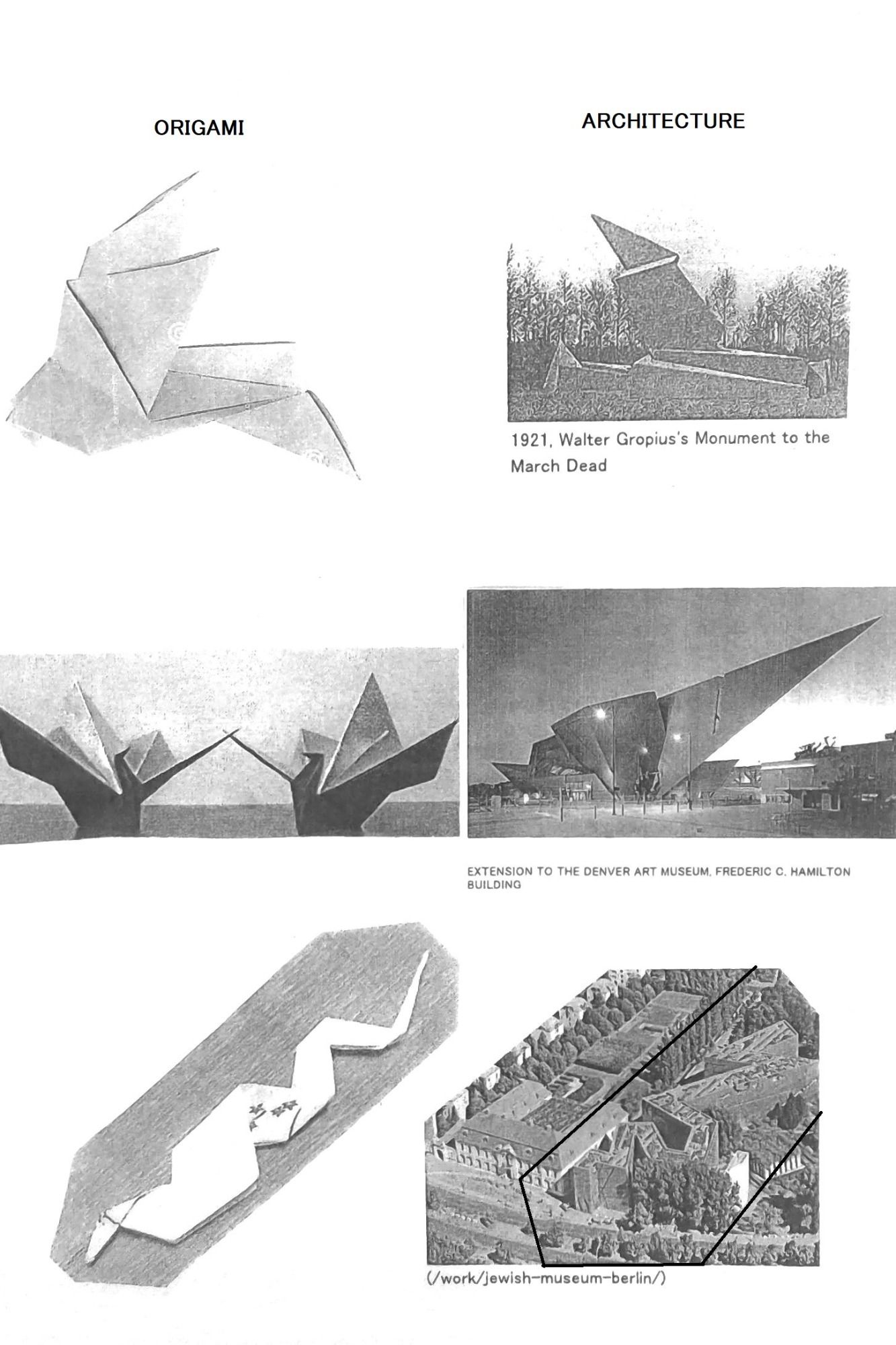

Origami and Walter Gropius' Monument to the March Dead, Weimar (1921/1922)

Origami and Daniel Libeskind's Extension to the Denver Art Museum (2006)

Origami and Daniel Libeskind's Jewish Museum, Berlin (2001)

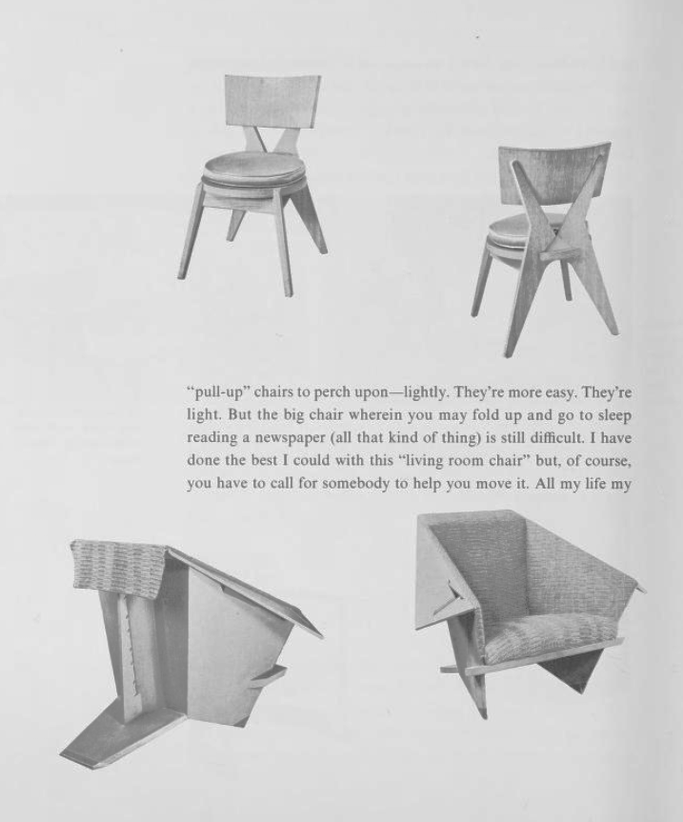

Origami and Frank Lloyd Wright's Taliesin I chairs (1949)

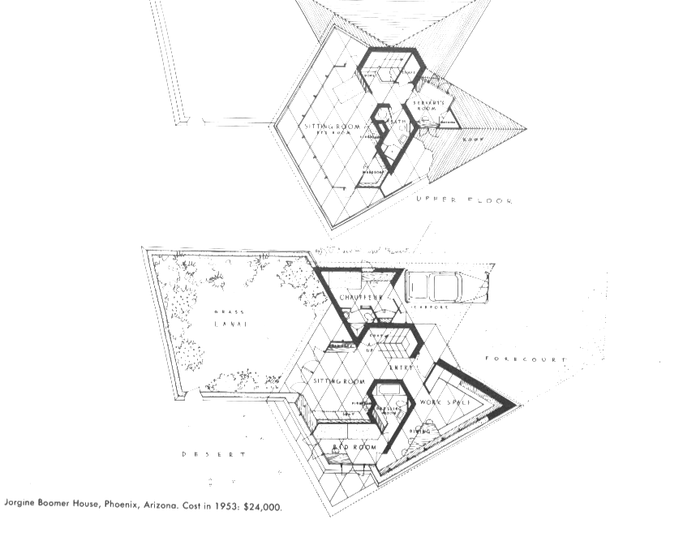

Origami and Frank Lloyd Wright's Boomer House, Arizona (1953)

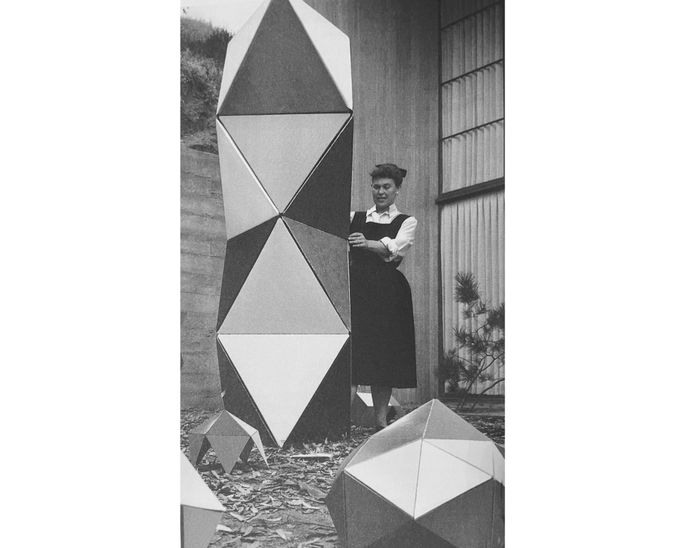

Origami and Charles and Ray Eames' 'The Toy' product prototypes (late 1940's to 1951)

Origami and Le Corbusier's painting, Persistantes Souvenances du Bosphorus (1913)

Origami and Le Corbusier's sculpture, Icône (1953)

Origami and Benjamin Woo / Guerin Glass' Kai La'i Hotel, Honolulu (2009)

For other examples of F. L. Wright's use of origami see Pablo De Souza Sánchez's valuable paper, 'Origami Folding Patterns in the work of F. Ll. Wright' in Felix Escrig and Jose Sanchez (eds.) Proceedings of the First Conference Transformables 2013. In the Honor of Emilio Perez Piñero. 18th-20th September 2013. School of Architecture Seville, Spain. Editorial Starbooks, 2013.

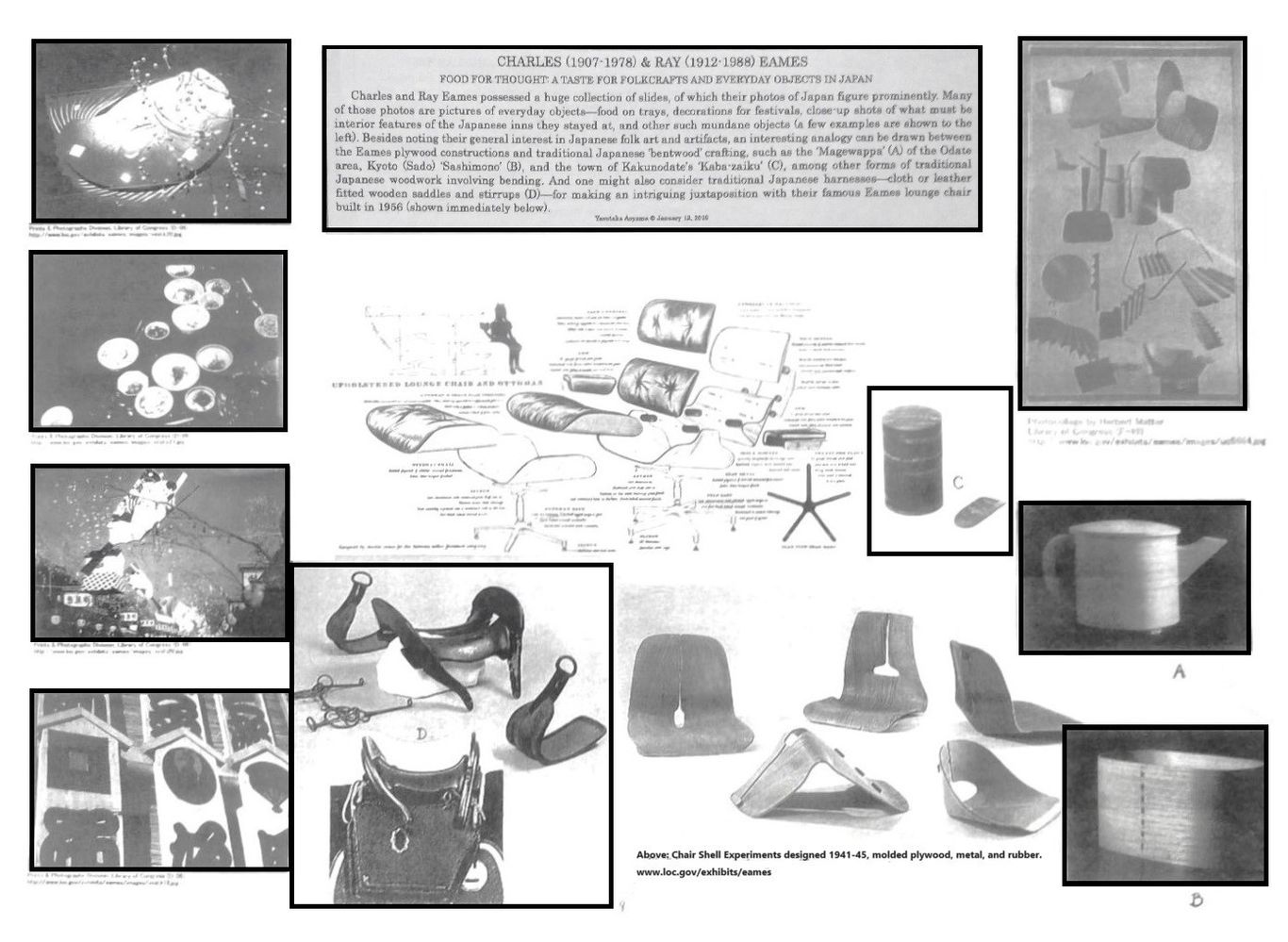

Charles and Ray Eames were not only architects but also entrepreneurs, who, like Charlotte Perriand, had a strong interest in Japanese folk crafts, as can be surmised from their extensive photographs and collection of Japanese artefacts. Their 'The Toy' product and other ideas often have strong parallels to Japanese crafts, even if the material and scale of things are dramatically changed (e.g. hand-sized paper to tree-sized plywood creations). Many of the shapes that can be found in photos of them at work are similar to relatively simple origami forms.

Regarding Le Corbusier's sculpture 'Icône' (1953) above right, an illustration from Aso Reiko's Origami Ningyo (2002) of traditional origami Okesa dancers of Sado Island has been provided for comparison, which are very similar to Le Corbusier's scuplture; but even closer (though the author has no examples at hand) to the Le Corbusier composition are traditional origami and bamboo figures of Awa Odori dancers of Shikoku, where the female dancer is like Le Corbusier's tall figure, while male Awa Odori dancers squat low, holding a lamp or fan outward, as suggested in the Icône sculpture by the lower figure (face and limb-like lines can be made out if one looks carefully). See 'Architectural Japonisme III' on this website for more on Le Corbusier.

Regarding the above origami-like textured exterior surface of the Ka La'i Hotel, a strong interest in Japanese traditional aesthetics can be verified in other works of Guerin Glass Architects, who designed that aspect of the exterior. In fact, a Japanese feel permeates much of their work; their Cabana Villa (Los Cabos, CA), for example, replicates the use of senbonkoshi along with a Japanese sense of delicacy. For most architects working in Hawaii, references to Japanese design are common; Benjamin Woo's One Ala Moana, for instance, incorporates shoji design expanded over the exterior surfacing, and other Japanesque wood elements are interspersed outside and inside the building.

The worldwide spread of origami as a children's pastime, and its influence upon the general popularity of paper dolls, was also part of the japonisme movement. Perhaps burgeoning interest in origami in the early 20th century and creative associations with it, for instance Johnny S. Black's lyrics, 'Paper Doll' (c.1915), released as a Mills Brothers song in 1943, were imaginative stimuli towards the application of origami concepts in architecture and modern art. Origami in Japan was always a serious art form as well as a children's pastime which adults---men and women---engaged in. The novelty of such an idea for Americans, even in the latter 20th century, was expressed by Thomas I. Elliot in his translator's note to Toyoaki Kawai's Origami (Tokyo: Hoikusha, 1970):

"As a full-grown, red-blooded male I have numerous preconceptions about things a man is supposed to do or not do. Men do not get hair permanents, for example, or otherwise let anyone fool with their hair except to cut it. Also, playing with paper dolls is for girls, and the closest a guy appraches a paper doll is in the famous song where he "buys a paper doll that other fellows will not steal. Today, hair permanents for men have become fashionable, especially in Japan. I am so brainwashed, though, that I still cannot imagine myself ever getting one. Playing with paper dols, however, is suddenly an animal different from my conception. It is inaccurate to call ORIGAMI "paper dolls," of course, but I think my point is made. Mr. Kawai takes "playing" with paper out of age and gender categories."

And perhaps out of the category of paper and dolls, and into the category of art, and by extension, by others into the category of architecture.

Uploaded before 2023.5.30, revisions 2024.5.30

Cubism as a 2-Dimensionalizing Origami Conceptual Transmutation

Or 'Gestalt' from 1 Dimension to 3 Dimensions to 2 Dimensions

Yasutaka Aoyama

Not enough has been devoted to the serious study of origami as an art form, one that is truly representative of the creative genius of Japan's traditional culture. Its sculptural and architectural qualities appeal to the trained eye, for contained within is a geometric paradigm of its own, a sort of 'hyper-Euclidean' universe originating from a single plane. Are there not perhaps untapped mathematical ideas, or those that we are unawares that derive from it? Lacan, at least, probably recognized its potential for furthering philosophical insight, as certain of his psychoanalytic diagrams are analogical to origami, and have been discussed that way (e.g. Janet Lucas, 'Lacan and 'origami': A Three-Tiered Topolgraphical Approach to Psychosis, Letters and Their Relation to the Unconsciousness', presented at The California Psychoanalytic Circle's 2nd Annual Symposium, May 12th-13th, 2001, San Francisco). Or consider Gilles Deleuze's Le Pli (The Fold 1988), which sounds like a origami interpretation of the baroque way of thinking and logical abduction, a metaphysics of the technique of origami folding, where contradictions and divergences can be synthesized into a congruent whole. Has not Deleuze abstracted the physical folding of origami, which of the same material transforms itself into a new entity, something with different aesthetic meaning? And is not that, and the examples shown above, the seeds of Greg Lynn's idea of 'Folding Architecture' (Architectural Design, 1993 special issue)? While formulated in the terminology of digital software and modeling, and cloaked in the abstractions of the 'anexact' and complex geometry or otherwise morphing technology, when uncloaked, simply a first dawning of the possibilities of folding by witnessing the act of origami creation before one's very eyes in a matter of seconds? That is to say, the wellsprings of a complex theory, once set in motion, while taking on a new technological and intellectual apparatus, lie in something like an apple or child's play---the surprising virtuosities of origami folding and the unexpected forms they create. Going beyond architecture, origami as a seed, a flash of insight, a possible source for the development of Cubism and abstraction in art makes perfect sense---if one just steps outside the simple box of fixed historical conceptions.

________________________

Charles and Ray Eames

Charles (1907-1978) and Ray (1912-1988)

Adapting the Japanese Outlook on Life to the American West

(Lecture handout 2016.1.12, Architectural Juxtapositions, 2016, p. 8)

Yasutaka Aoyama

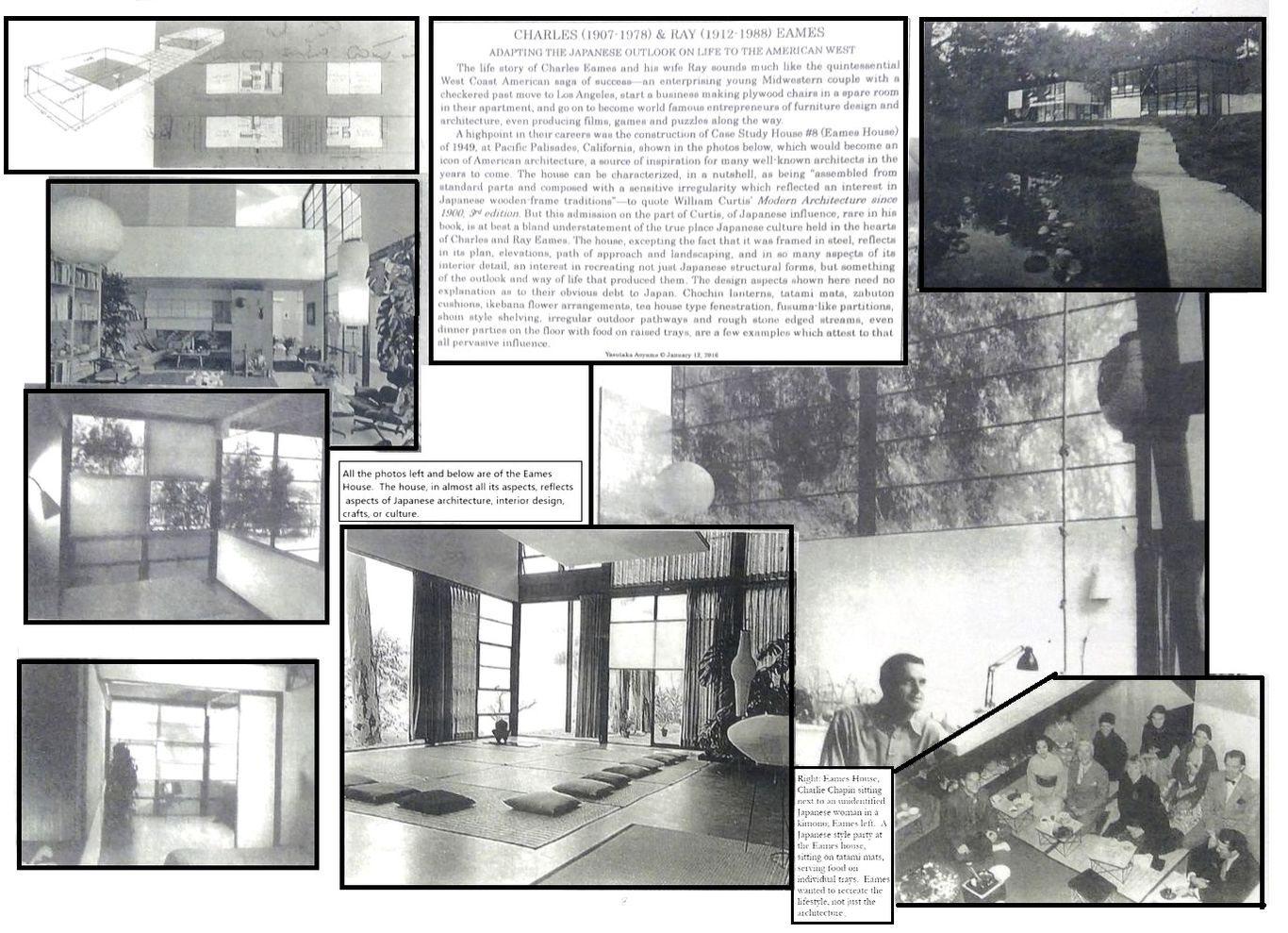

The Eames House as part of a general effort to emulate a Japanese lifestyle. Note in the lower right hand corner a photo of a party in Japanese style hosted by the Eames at their house. The man to the right of the Japanese woman in the kimono is none other than Charlie Chaplin; Charles Eames to the far left. The article 'An Afternoon Tea at the Eames House' (2023) by Nieves Fernández Villalobos and Alberto López del Río, University of Navarra (original article in Spanish: Una tarde de té en la Casa Eames. Ra. Revista De Arquitectura, (25), 138-151) is a wonderfully enlightening paper---highly recommended reading, and can be found in English translation at the University of Navarra website (https://revistas.unav.edu/index.php/revista-de-arquitectura/article/view/45646).

Text further below reproduced for better legibility:

The life story of Charles Eames and his wife Ray sounds much like the quintessential West Coast American saga of success---an enterprising young Midwestern couple with a checkered past move to Los Angeles, start a business making plywood chairs in a spare room in their apartment, and go on to become world famous entrepreneurs of furniture design and architecture, even producing films, games and puzzles along the way.

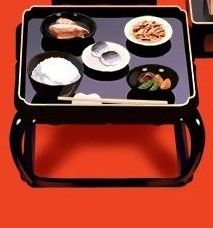

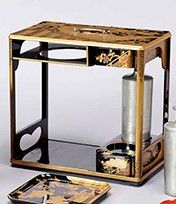

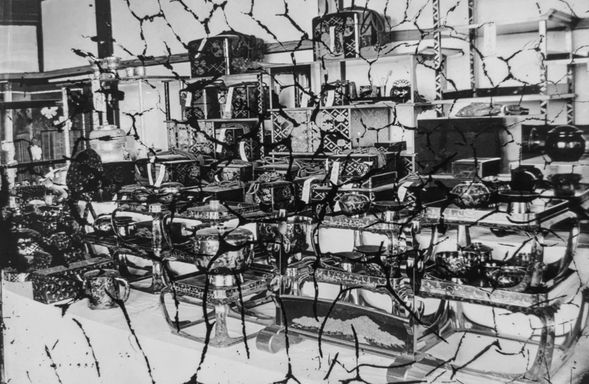

A high point in their careers was the construction of the Case Study House #8 (Eames House) of 1949, at Pacific Palisades, California, shown in the photos below, which would become an icon of American architecture, a source of inspiration for many well-known architects in the years to come. The house can be characterized in a nutshell as being “assembled from standard parts and composed with a sensitive irregularity which reflected an interest in Japanese wooden-frame traditions”---to quote William Curtis’ Modern Architecture since 1900, 3rd edition. But this admission on the part of Curtis, of Japanese influence, rare in his book, is at best a bland understatement of the true place Japanese culture held in the hearts of Charles and Ray Eames. The house, excepting the fact that it was framed in steel, reflects in its plan, elevations, path of approach and landscaping, and in so many aspects of its interior detail, an interest in recreating not just Japanese structural forms, but something of the outlook and way of life that produced them. The design aspects shown here need no explanation as to their obvious debt to Japan. Chochin lanterns, tatami mats, zabuton cushions, ikebana flower arrangements, tea house type fenestration, fusuma-like partitions, shoin style shelving, irregular outdoor pathways and rough stone edged streams, even dinner parties on the floor with food on raised trays, are a few examples which attest to that all pervasive influence.

Charles and Ray Eames

A Taste for Folkcrafts and Everyday Objects in Japan

Lecture handout 2016.1.12, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 9

Yasutaka Aoyama

Charles and Ray Eames were avid photographers possessing a huge collection of slides, of which their photos of Japan figure prominently. Many of those photos are pictures of everyday objects---food on trays, decorations for festivals, close up shots of what must be interior features of Japanese inns they stayed at, and other mundane objects (a few examples are shown below to the left). Besides pointing out their general interest in Japanese folk art and artifacts, an interesting analogy can be drawn between the Eames plywood constructions and traditional Japanese 'bentwood' crafting, such as 'magewappa' (A) of Odate; 'sashimono' (B) of Kyoto; and the 'kabazaiku' (C) of Kakunodate, among other forms of traditional Japanese woodwork involving bending, not to mention an infinite variety of bamboo crafting involving bending of one sort or another. And one might also consider traditional Japanese harnesses---cloth or leather fitted wooden saddles and stirrups (D)---for making an intriguing juxtaposition with the famous Eames lounge chair built in 1956 (show below).

James Steele's 'The Japanese Influence' in his Eames House: Charles and Ray Eames (Phaidon Press, 1994)

The following are a few excerpts from James Steele's discussion of the history of Japanese influence upon American architecture leading up to the Eames House, and the fundamental change in the nature of that influence occurring in more recent times:

The Japanese Influence

"In a final non-parallel with high-tech dogma, there are historical references in the (Eames) house, albeit abstracted, that tie to a succession of well-established precedents in foreshortened, Los Angeles time, which are all related to the Japanese attitude toward interior and exterior space."

"The influence of the Japanese exhibition and the Ho-o-den Temple at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 has been well documented, and the Gamble House in Pasadena by Charles and Henry Greene is the the first and most complete synthesis of its transfer to southern California. ...the Gamble House may be seen to have irrefutable roots across the Pacific, as does the Bay tradition, which is a parallel, further north."

Steele speaks at length on Frank Lloyd Wright and Rudolph Schindler, as well as Richard Neutra, as incorporating Japanese architectural concepts and components into their work from the 1920's to the post WWII period, and from there moves on to the contemporary scene:

"While the Japanese equation is still an important aspect of many of the most well-known architects practising in Los Angeles today, such as Frank Gehry, Thom Mayne of Morphosis, Erik Owen Moss and Frank Israel, it is significant that the transfer has changed around completely to an emphasis on artificial rather than natural similarities. Paradoxically, these architects, who are considered to be trendsetters elsewhere, now regard Japan as the origin of innovation, the place to watch for new ideas, an urban soul mate beleaguered by similar problems, and subjected to comparable growing pains, which forces it to be equally creative in attempting to find solutions."

"The Edo ideals of purity, humility and oneness with nature that captivated the Greene brothers and Frank Lloyd Wright are distilled in the Eames House for the last time making it a bench-mark of that tradition in the city. From that point forward, it is the mastery of technology alone, rather than mystical notions about submission to natural laws that has been the envy of Los Angeles architects; and yet it has continued to captivate successive generations there, not because it is a modular re-interpretation of the Tatami generated palaces of Japan's classic period, but because it is built in steel, and improbably and almost magically balances strength with lightness."

________________________

Adolf Loos (1870-1933)

Part I: Japan from the Inside

Lecture handout 2015.11.20 and added material 2023 summer, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 10, last revision 2024.7.30.

Yasutaka Aoyama

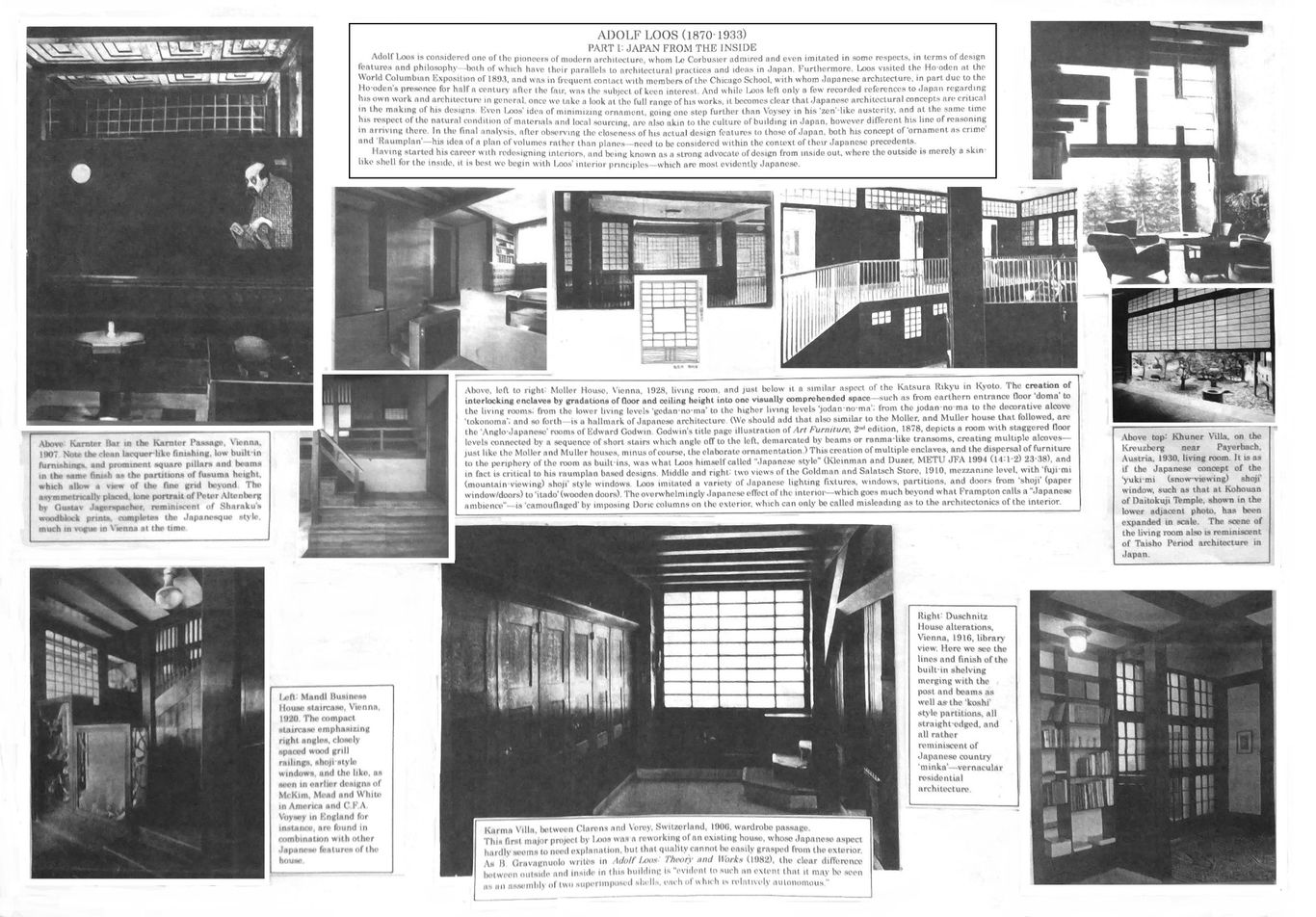

Adolf Loos is considered one of the pioneers of modern architecture whom Le Corbusier imitated in some respects, in terms of both design features and philosophy, which in turn have parallels to architectural practices and ideas in Japan. While Loos left only a few recorded references to Japan, once we take a look at the full range of his work, it becomes clear that Japanese architectural forms and principles are present throughout his designs, an unavoidable conclusion reached for those that know both his work and Japanese architecture, such as Yoshio Sakurai, who has devoted his life to recreating the complete opus of Loos's works in models with painstaking, detail with his students (See Radio Prague International, 'Japanese professor brings ‘Raumplan’ of visionary architect Adolf Loos to life in models' 3/20/2019 at https://english.radio.cz).

Besides plentiful books and prints available in Europe and America by the late 19th century to gain knowledge of Japanese design, Loos also had the opportunity to experience Japanese architecture first hand through his visit to the Hooden at the World Columbian Exposition of 1893, held in Chicago; and was in frequent contact with members of the Chicago School, for whom Japanese architecture, in part due to the Hooden's presence in Chicago for half a century after the fair, was an ongoing subject of interest.

Despite the stark contrast from the outside of his designs with those of Japanese architecture, and his ample use of concrete and marble, Loos employs traditional Japanese forms in his window designs, his ceiling treatments, his built-in cabinetry, his sliding screens, lighting fixtures, and in his approach to asymmetry. Loos' idea of minimizing ornament, going one step further than Voysey in his 'zen'-like austerity, resonates with Japanese architectural values; and his stated respect for the natural condition of materials and local sourcing is also akin to the culture of building in Japan---however different his stated line of reasoning in arriving there. Should one take the time to evaluate the parallels of his actual design features to those of Japan, along with his concepts of 'ornament as crime', or his attitude toward construction materials, or his 'Raumplan' with its focus on interlocking volumes and not only planes in the making of plans, it would become apparent to the unprejudiced observer that there is a need to re-consider Loos' specific designs and general philosophy within the context of their Japanese precedents. Loos himself wrote in 1898:

"The Orient was the great reservoir from which fresh seed constantly poured into the West. It almost seems as if at present Asia has given us the last vestiges of its inherent strength. We have had to reach out to the farthest corners of the Orient, to Japan and Polynesia, and that is where it finished." (in Stewart, 2000, p. 71)

Here, in the comments of the young Loos, we have an admission of the tremendous influence of the Orient, including that of Japan, upon European art; and at the same time an aversion, an attitude of 'enough is enough' towards such exotic influences. Indeed, as Janet Stewart in her Fashioning Vienna: Adolf Loos's Cultural Criticism (Routledge, 2000) discusses, Loos was worried Japan would overtake and lead Austria in reaching the "heights of Western civilization" (p. 67)---in perhaps a somewhat similar mindset to that of Europeans and Americans in the 1980's facing the economic juggernaut of Japan.

Loos' generally pessimistic comments and stereotyping of Japanese design have been one of the reasons the influence of japonisme on his work has been underplayed, despite the striking parallels to be found. The lack of an open admission of influence and inspiration, however, does not prove that a link does not exist; the best criteria of that lies in his designs themselves, and in the direction the circumstantial evidence points---that is to apply the same criteria of art history in tracing streams of influence and styles between Europeans, and otherwise around the world. For reticience, regarding japonisme, is most notable in modern architecture more so than in other areas of art, both by the architects themselves, and by historians of modern architecture, who hardly ever mention the torrent of interest in Japan which was engulfing European artistic circles at the time. A good example of japonisme is found, for instance, in the paintings and folding fan art of the painter Oskar Kokoschka, (1886–1980), a close friend of Loos.

Having started his career with redesigning interiors, and being known as a strong advocate of design from inside out, where the outside is merely a skin-like shell for the inside, it is best we begin with Loos' interior principles---which are most evidently Japanese.

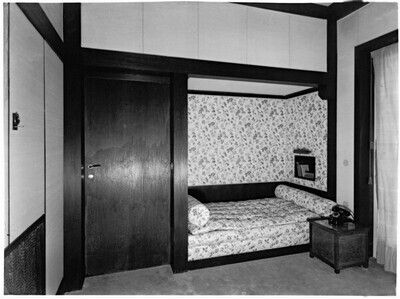

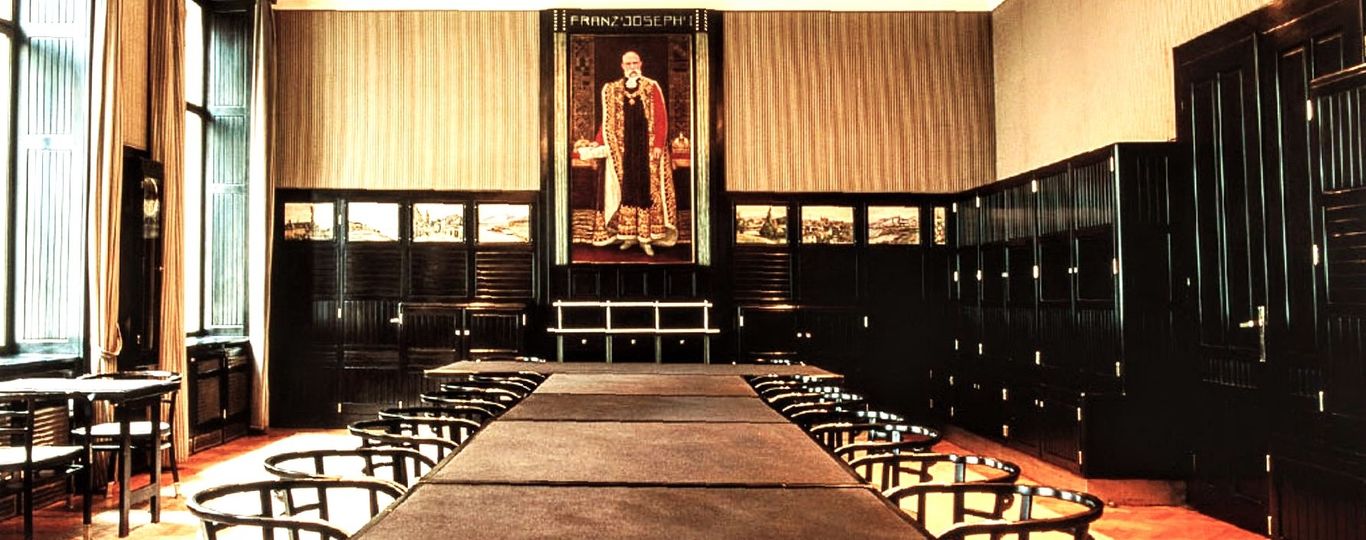

Hugo Semler Apartment, Pilsen, Czech Republic, 1930

Above is the Adolf Loos interior designed Hugo Semler Apartment, Pilsen, Czech Republic (1930), interior sliding doors. A marble surround replaces what would be wood in Japan, glass replaces paper, the screens are hung without rails below, and a lock is added---a case of material conversion and design elaboration, but the basic form and functioning, the conception and the aesthetic, is the same as its Eastern prototype. In fact, this type of framed glass sliding screen was already common in Japan, both in newly built or renovated Japanese style houses, as well as in mixed European-Japanese style houses, since the late 19th century.

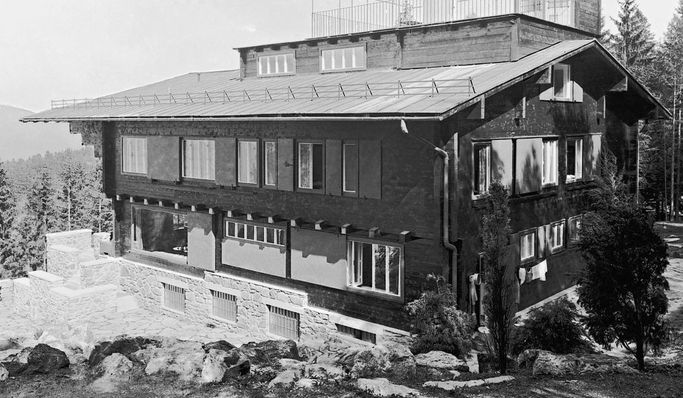

A closer look at the interior of the Loos designed Villa Khuner

Descriptions of the Villa Khuner in biographies and architectural histories portray the villa as being one influenced by Swiss chalet architecture. Be that as it may, it does little to explain its unique quality. The important question is not that it takes from Swiss chalet architecture; but rather, why is the result so different, and what makes it different, from traditional Swiss chalet architecture?

The answer, as the reader is surely already expecting, is the Japanese element. It can be argued that the Villa Khuner can be better understood by seeing its origins in Japanese architecture that was built in the years preceding his design of the Villa, that is during the Meiji and Taisho periods.

Interior photos of the Loos designed Villa Khuner, Payerbach, Austria, built in 1930 shown below. Around this time, Loos' preoccupation with Japanese interior effects is quite evident.

The first two photos of Villa Khuner (1 and 2) look as if directly from the interior of a late Meiji or Taisho period (c. 1875-1925) Japanese hotel lobby and stairway.

The ceiling light in (3) is very much like that found in Japanese hotels, inns, & private residences from the latter Meiji period onward; the reason such fixtures were often quite flat is not only stylistic, ceilings were often much lower in Japan than in the West, and where traditionally there was no ceiling lighting but only floor andon, ceiling fixtures naturally developed horizontally rather than vertically. Even the outdoor view seems to have been inspired by the Japanese example; a low rocky landscape has been created with an irregular flight of steps, reminiscent of a Japanese garden.

In the last photo (4) note how the bed is virtually on the floor, the closest one can get to a futon without becoming one. The whole room is outlined by straight, thick exposed woodwork in the typical fashion found in Japanese hotels and homes. The small alcove in which the bed is placed, is approximately of the dimensions of a 'oshiire' in an average Japanese bedroom, where the sleeping futon mattress is stored. The Japanese hotels shown further below catered to Western visitors and Japanese visitors wishing to stay at a Western style hotel, and thus beds are provided, though still at a much lower level and with low headboards compared to a traditional western bed. Seating levels of chairs and couches, as in the Villa Khuner, are also much lower than what was typical in the West until well into the 20th century.

Now if we look at some Japanese examples it becomes clear as to just how similar Loos' approach was to Japanese architectural design around the turn of the century. Below we have in the first row, Nara Hotel, 1909. Second row, Manpei Hotel, 1894. In both cases, the general interior design is preserved in essentially in its original state, and hotel room interiors have been renovated closely to the original look, excepting of course modern amentities and appliances.

Nara Hotel, 1909

Manpei Hotel, 1894

Adolf Loos

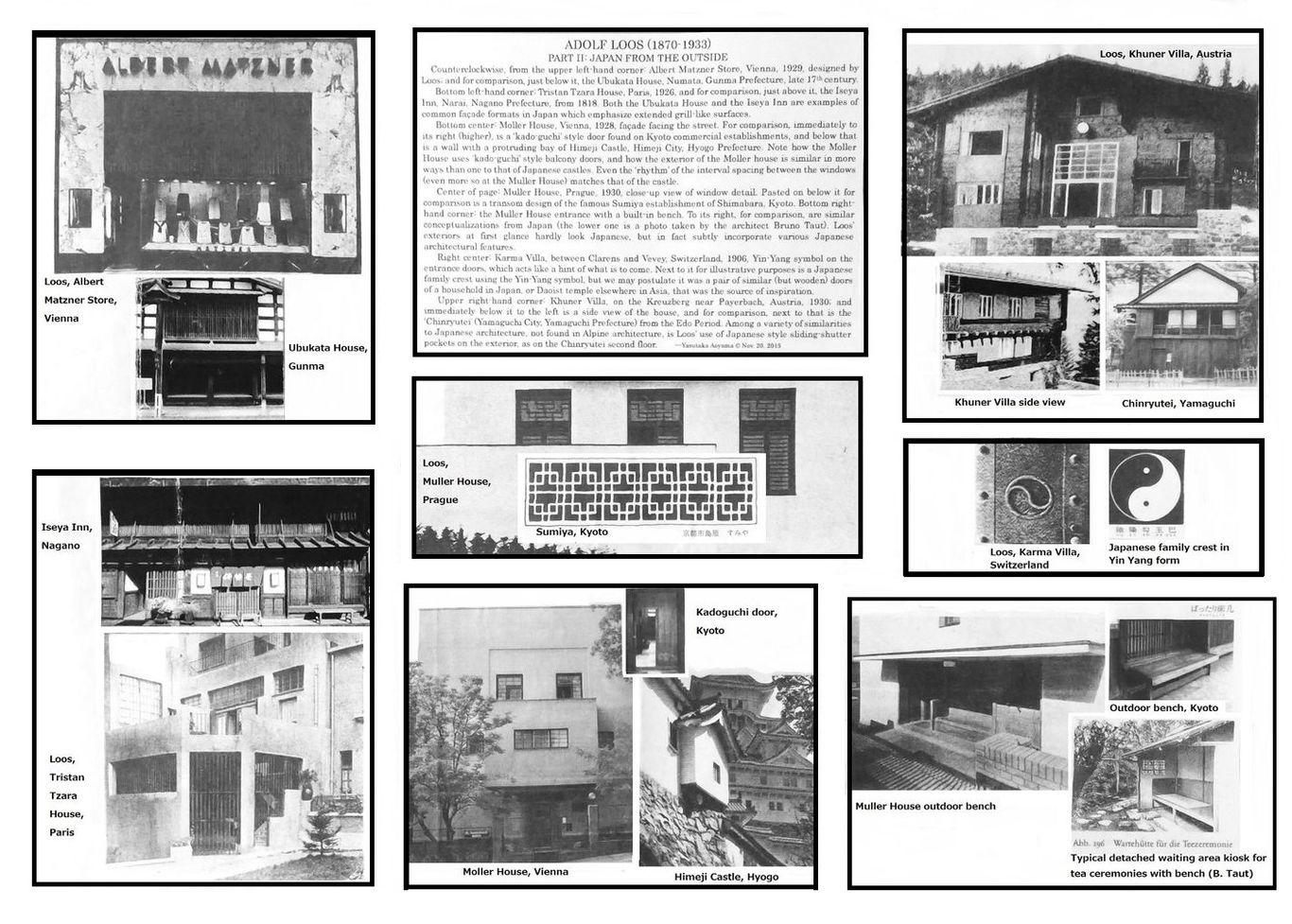

Part II: Japan from the Outside

Lecture handout 2015.11.20, added material 2023 summer, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 11

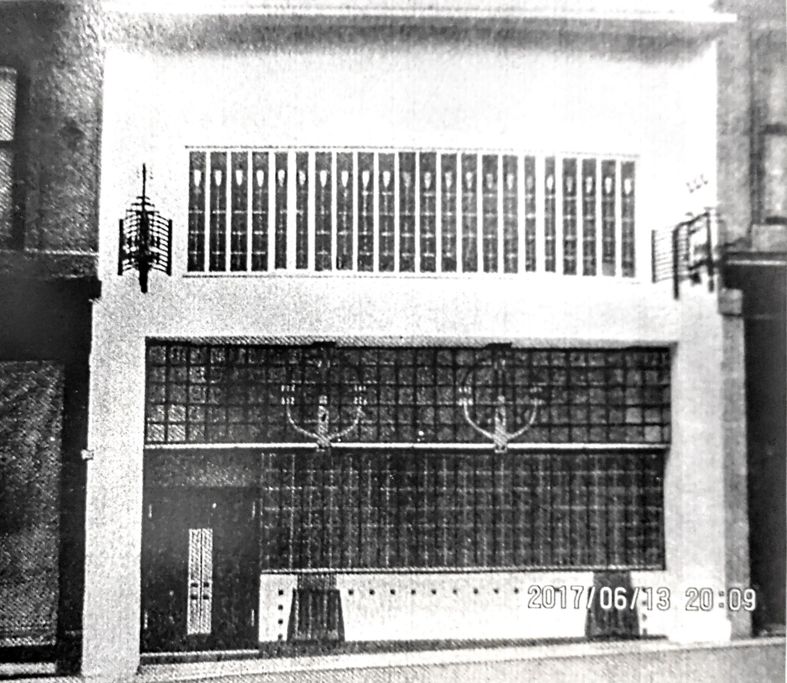

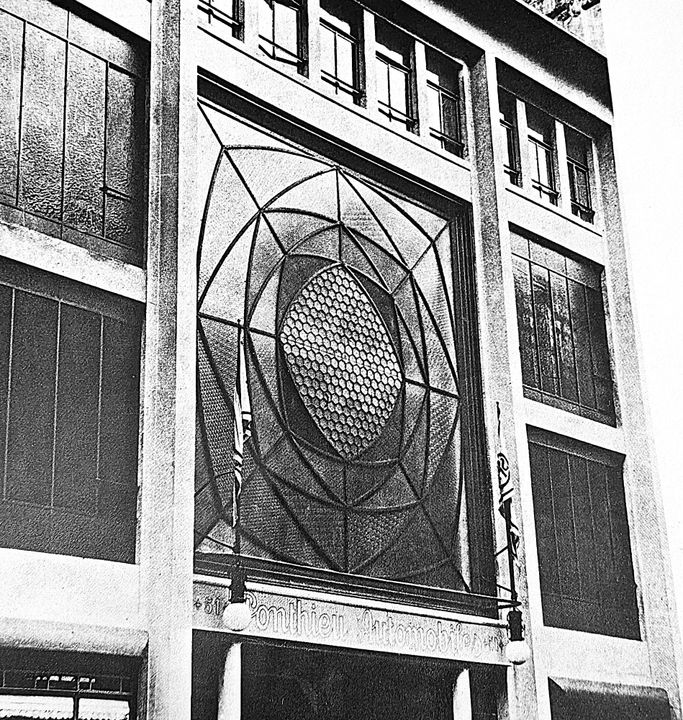

On the second floor of the Albert Matzner store (in the above upper left corner), though looking like a dark, uniform surface in the photo, actually it is a rectangular block of closely spaced vertical grillwork, similar to the Japanese house below it.

A closer look at the exterior of the Loos designed Villa Khuner

Note in the photo of the exterior to the left the sliding 'amado' (Japanese rain shutter) style panels over large windows, jutting out over the ground level with rafter ends painted, the variation in ground level fenestration sizes, and the style of landscaping with rocks and trees/shrubs, all which are characteristics of Japanese architecture. To the right is the front facade, with its conspicuously accentuated asymmetry of windows and door placement and sizes, and changing depth of the facade, also found in Japanese architecture. And below a close-up of the Villa Khuner sliding 'amado' equipped large windows and for comparison to its right the Chinryutei sliding shutters over contiguous windows.

Moller House, 1928

Aspect of Loos' Moller House facade with shoji reminiscent windows.

________________________

De Stijl Japonisme from Doesburg to Rietveld

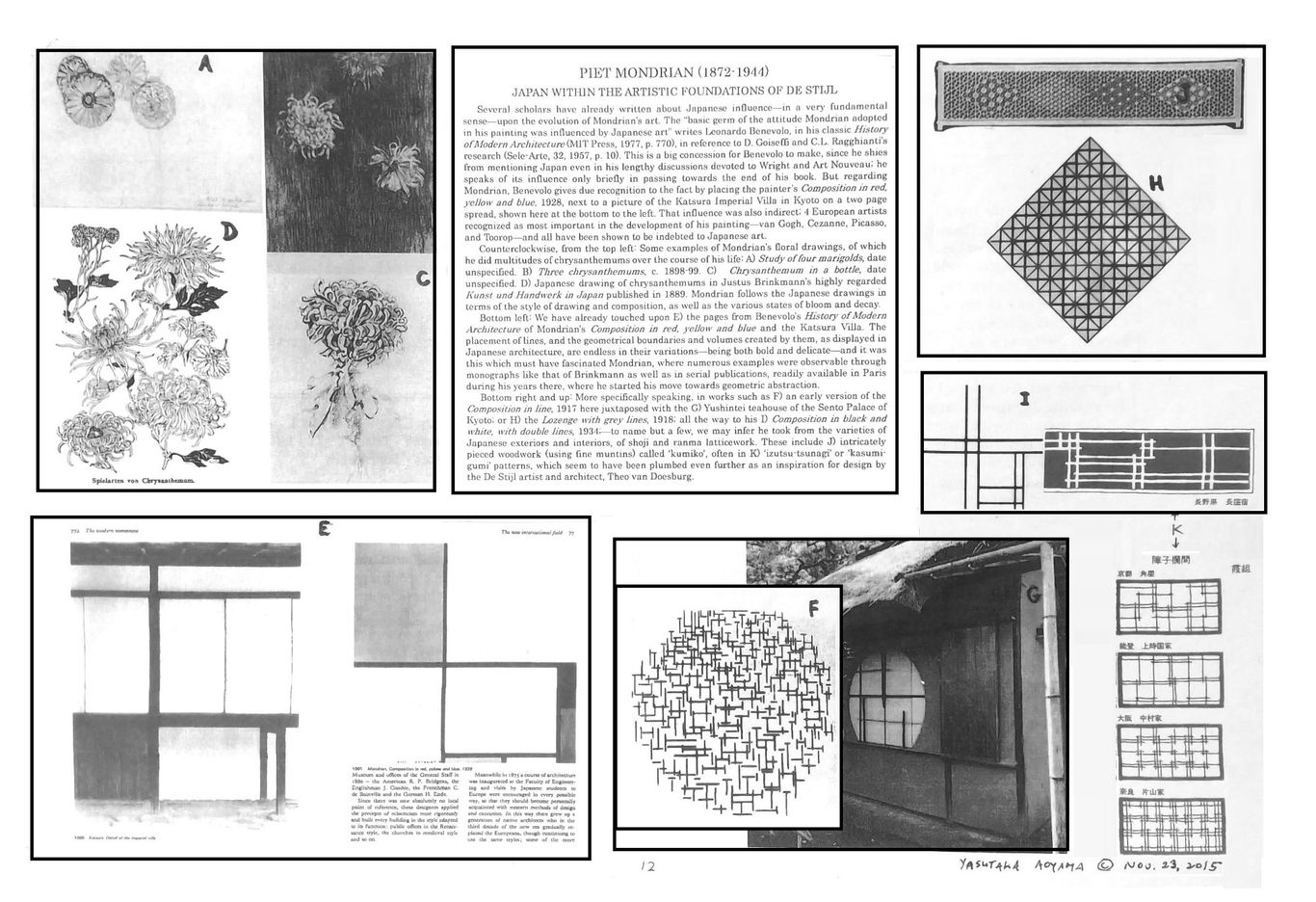

Piet Mondrian (1872-1944)

Japan within the Artistic Foundations of De Stijl

Lecture handout 215.11.23, Architectural Juxtapositions, p.12

Yasutaka Aoyama

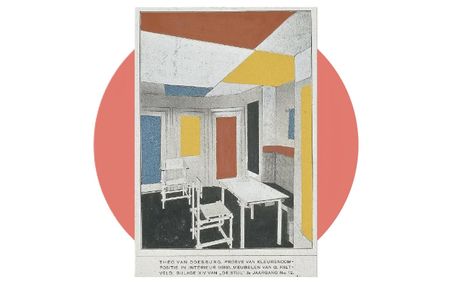

"...the true prehistory of Mondrian after 1919 must be sought in the traditional architecture of Japan. Structure, division of space, mood, certainly; but also the precision with which the wall unfolds like a musical score..."

Decio Gioseffi, eminent Italian art historian, quoted in Maria Grazia Ottolenghi, L'opera completa di Mondrian, 1974

"Mondrian's works after his breakthrough to abstraction suggest a new kind of Japanese reference, unconscious on Mondrian's part: it does not relate to woodcuts but to the basic idea of Japanese domestic architecture. The rhythmic use of standard components--squares, vertical or horizontal rectangles, narrow and wide proportions, standardized floor mats related to wall surfaces, the black 'sticks', vertical and horizontal, in 'suspended equilibrium' (Piet Mondrian, Neue Gestaltung, Bauhausbucher no. 5, Munich, 1925), and the avoidance of curves and ornament: all these are already present in the Bosen Tea-Room (Daitokuji Temple) in Kyoto..."

Klaus Berger, Japonisme in Western Painting from Whistler to Matisse (1980, translation 1992)

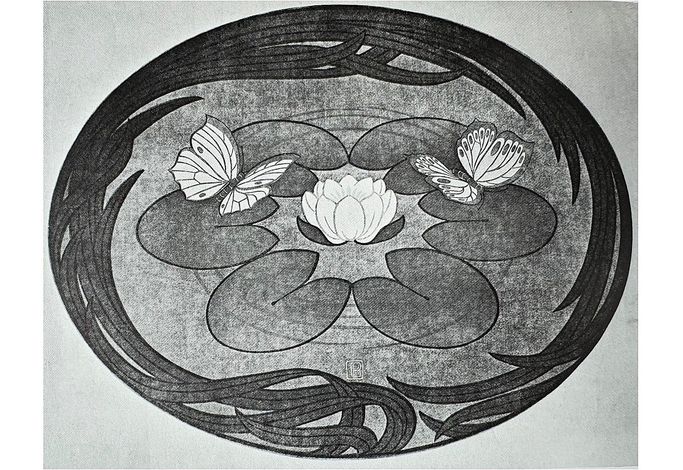

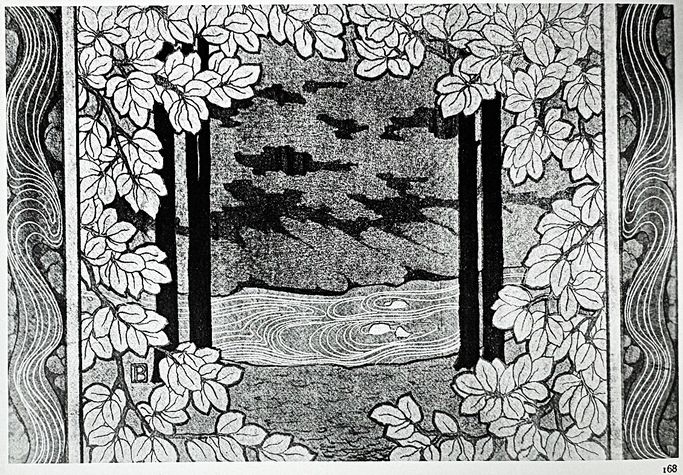

Japanese designs from Kawashima Choji, Nihon Minka Design Shusei. Tokyo: Nihon Tosho Center, 2013.

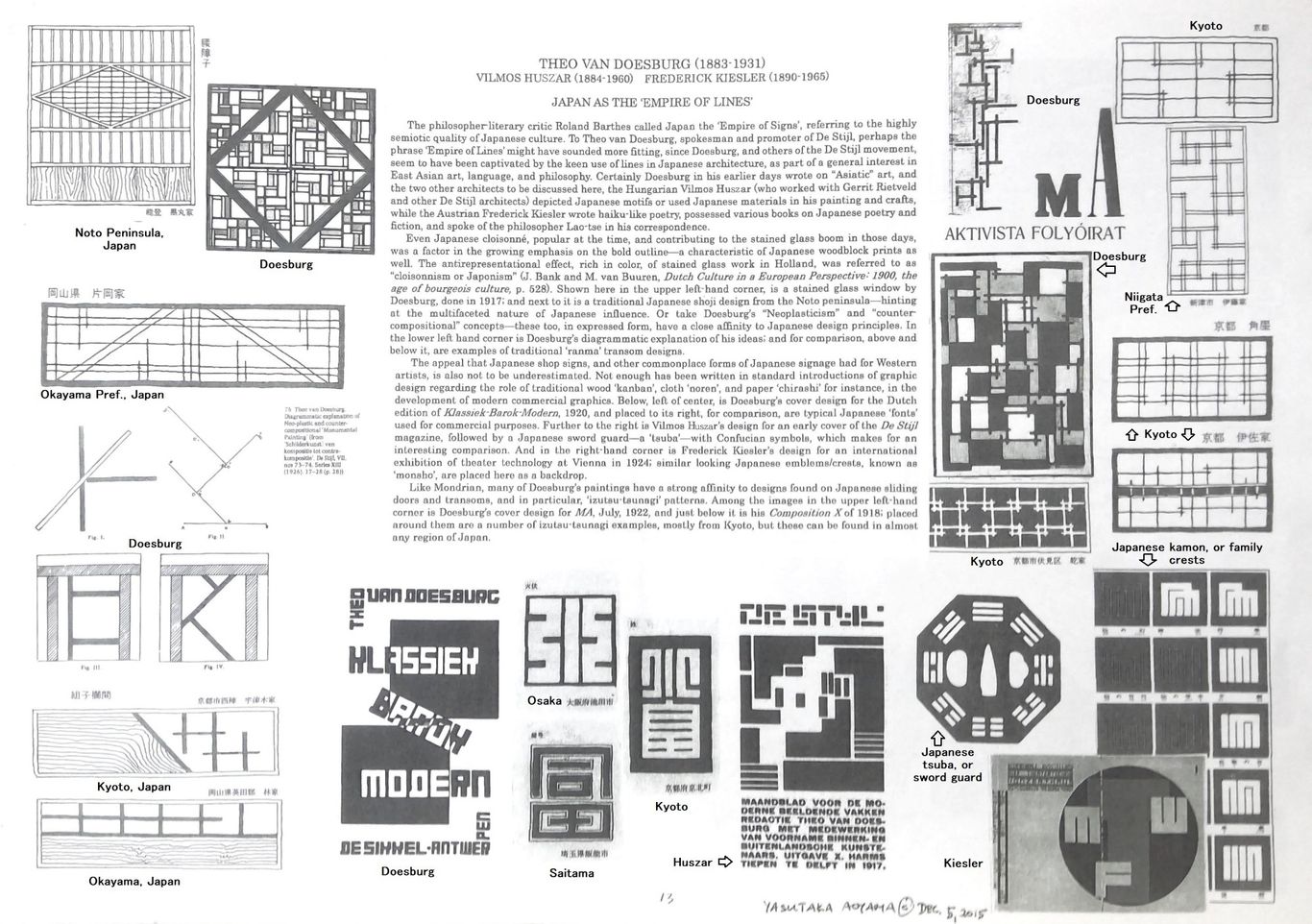

Theo van Doesburg (1883-1931)

Vilmos Huszar (1884-1960)

Frederick Kiesler (1890-1965)

De Stijl and Japan as the 'Empire of Lines'

Lecture handout 2015.12.5, Architectural Juxtapositions, p.13

Yasutaka Aoyama

Japanese designs primarily from Kawashima Choji, Nihon Minka Design Shusei. Tokyo: Nihon Tosho Center, 2013.

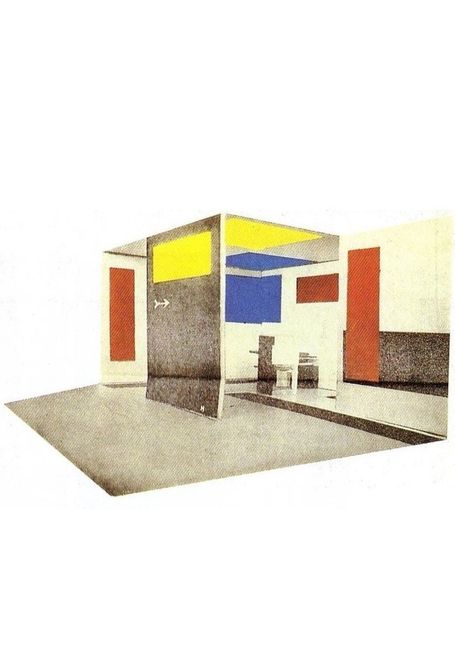

Gerrit Thomas Rietveld (1888-1964)

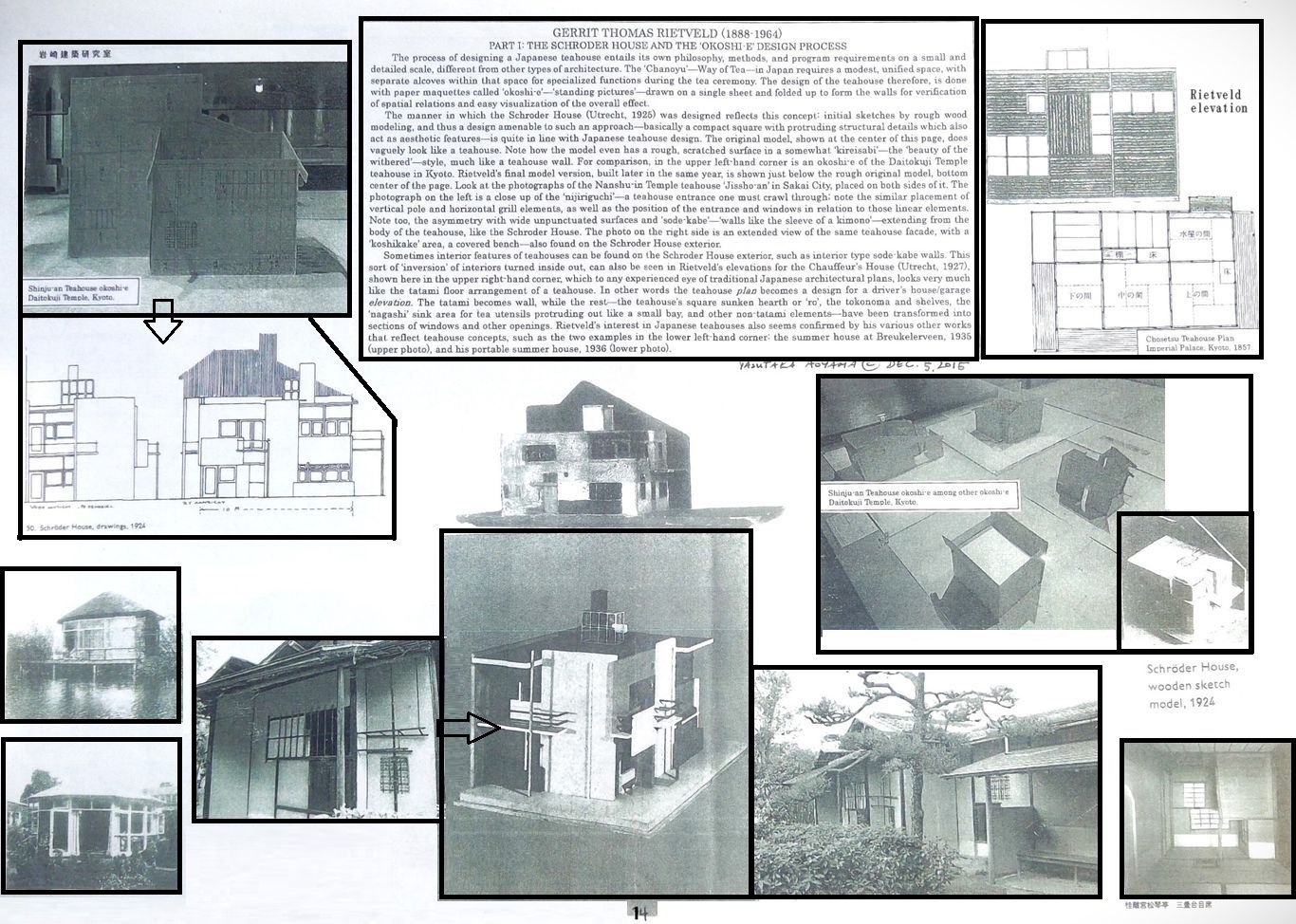

Part I: The Schroder House and the Okoshi-e Design Process

(Lecture handout 2015.12.5, Architectural Juxtapositions, p.14)

Yasutaka Aoyama

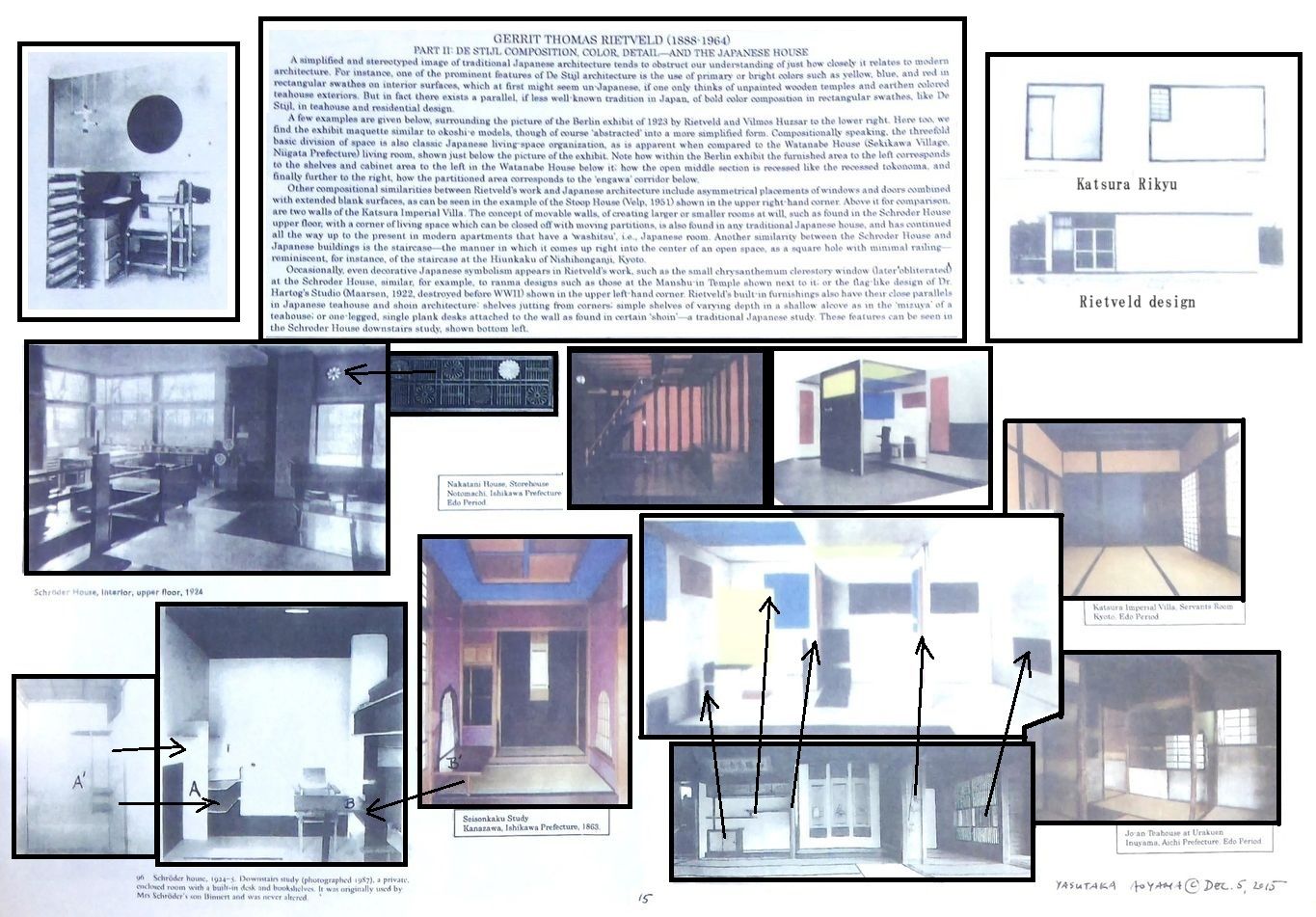

Gerrit Thomas Rietveld, Part II

De Stijl Composition, Color, Detail--and the Japanese House

Lecture handout 2015.12.5, Architectural Juxtapositions, p.15

Yasutaka Aoyama

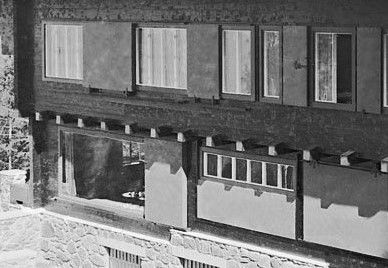

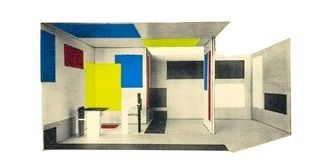

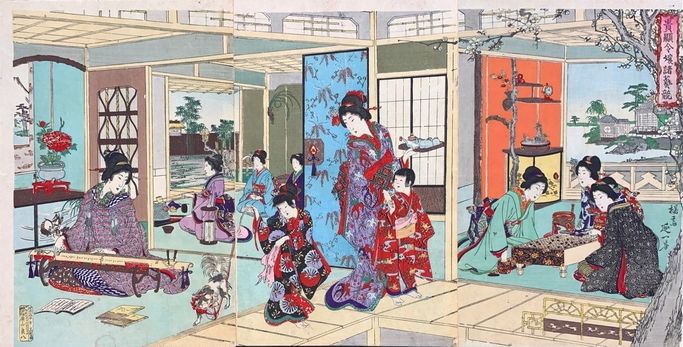

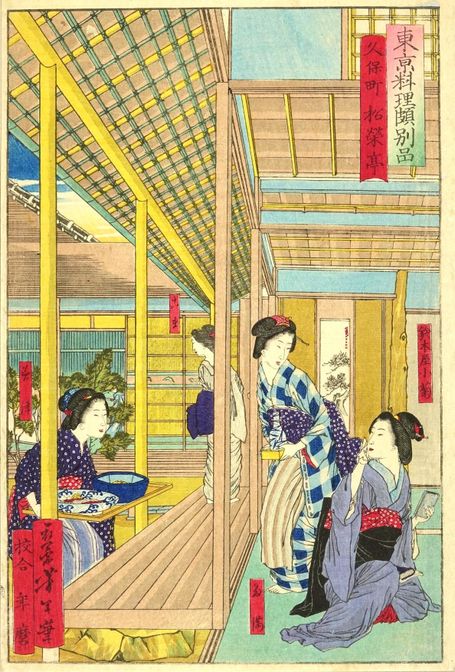

Below are some more Japanese interiors done in the latter 19th century, juxtaposed with a De Stijl style interior. As already shown in the examples above and another offered below right (Iwashina School, Matsuzakicho, Shizuoka, 1880), traditional room interiors often had surface sections that were contrastingly colored, which was made easy by the fact that wall and ceiling surfaces were never continuous, but always clearly demarcated by thick exposed wooden pillars and beams, and often of varying depth. This was not so easily done in traditional Western interiors, where walls, ceilings, and floors were often continuous and uninterrupted across wide surfaces. In Japan, all six surfaces of a room were clearly divided into sections, whether by sliding partitions, walls, cabinets, and tokonoma; the ceiling in exposed wood panels or squares with crosswise beams; and the floor too of course, in tatami mats. And with the coming of the Meiji period, there was a trend towards incorporating glass windows into architecture, at times colored, sometimes in bright geometrical patterns, often covering extensive surface areas, as they took the place of shoji sliding panels, as the example shown below left (Oyama Shrine, Shinmon third floor, Kanazawa, Ishikawa, 1875). In the center is an illustration of a Doesburg (interior) and Rietveld (furnishing) collaboration, from De Stijl, 3e Jaargang (3rd Year), No. 12., Bijlage (Appendix/Supplement) XIV.

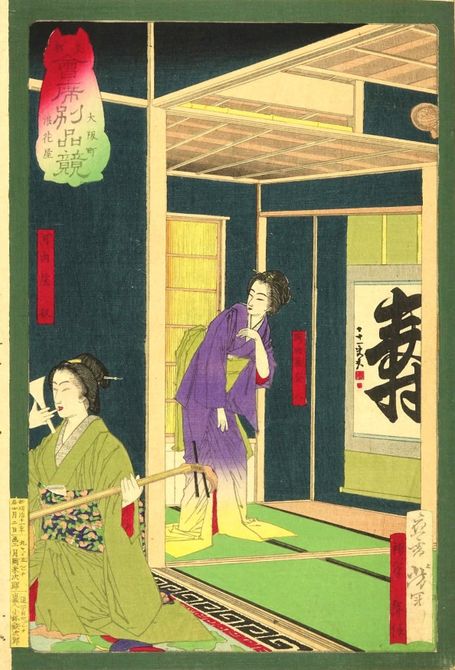

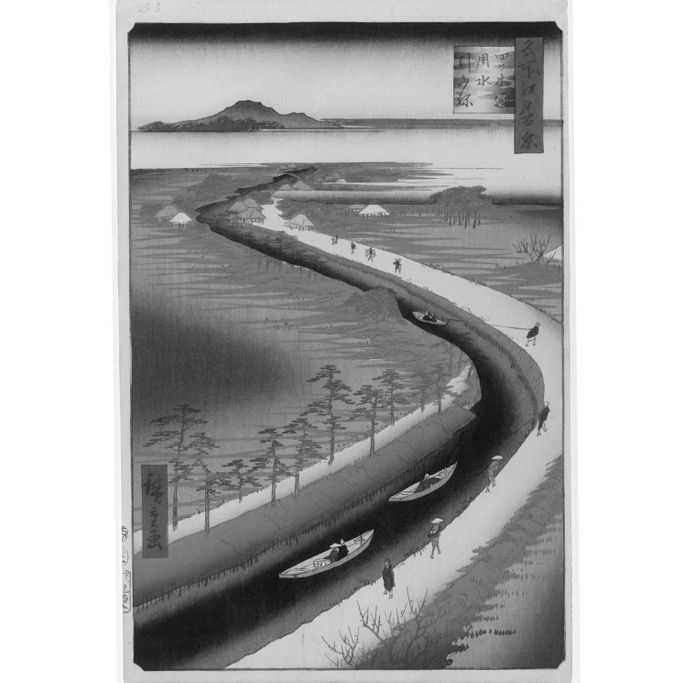

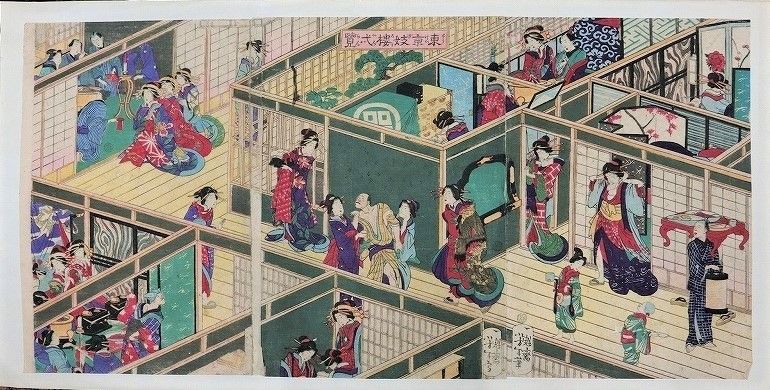

An accessible source of Japanese interior designs were ukiyoe prints of such interiors. Most of the Meiji era print artists produced scenes of rooms with bright, clearly sectionalized multi-colored walls and thin partitions/sliding panels, and these were especially popular from the 1870's to the 90's, among whom Tsukioka Yoshitoshi was particularly adept at illustrating (discussed in Architectural Japonisme III), though many other artists drew such pictures including Toyohara Kunichika and Yosai Nobukazu. Below are examples from Nobukazu and Yoshitoshi, juxtaposed with the 'Spatial Color Composition' by Gerrit Rietveld and Vilmos Huszar at the Juryfreie Kunstschau (Unjuried Art Show), Berlin, 1923.

As the japonisme researcher Anna Basham notes, "The similarity between Japanese architecture and modernist Dutch architecture is noted in Balbus, or the future of architecture (1926) in which the author and architect, Christian Barman discusses a modern Dutch house which has no fixed internal walls; rooms are created by the use of movable screens and compares this to the Japanese house: 'This is, of course, how houses are mostly constructed in Japan, but it should be remembered that, though the Japanese house is built entirely without walls, whether internal or external, it yet exhibits the utmost complexity and formal refinement in the general lines of its design. The plan is there, though only its skeleton is permanent, and wall-divisions are made movable ...' " (From Victorian to Modernist: the changing perceptions of Japanese architecture encapsulated in Wells Coates' Japonisme dovetailing East and West, doctoral thesis, University of the Arts London, 2007, pp. 196-7).

Left: chair in black lacquer with gold-yellow painted flat cut ends, by Gerrit Rietveld, 1917; right: chair in black lacquer with gold finished flat cut ends, the 'Sekishitsu Tsukinokinokosho' of the Shosoin storehouse in Nara, 8th century. While the Shosoin chair does not use red, other such Nara and Heian period chairs did; the more recent (but according to ancient tradition) Emperor's chair in the Shishinden, Kyoto Imperial Palace, for instance, does. Black, red, and gold are a classic color combination in Japanese lacquered furnishings.

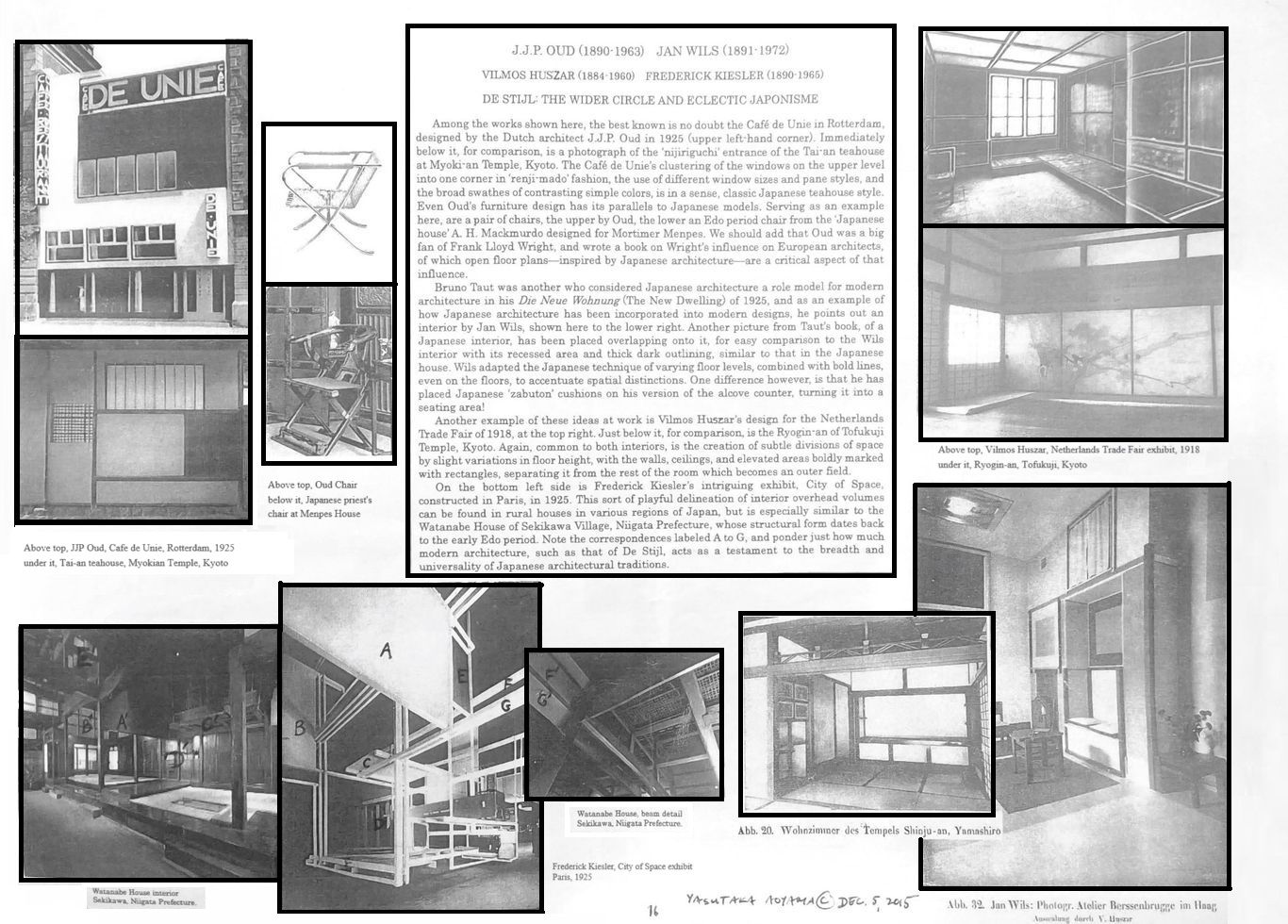

J. J. P. Oud (1890-1963)

Jan Wils (1891-1972)

Vilmos Huszar

Frederick Kiesler

De Stijl: The Wider Circle and Eclectic Japonisme

Lecture handout 2015.12.5, Architectural Juxtapositions, p.16

Yasutaka Aoyama

________________________

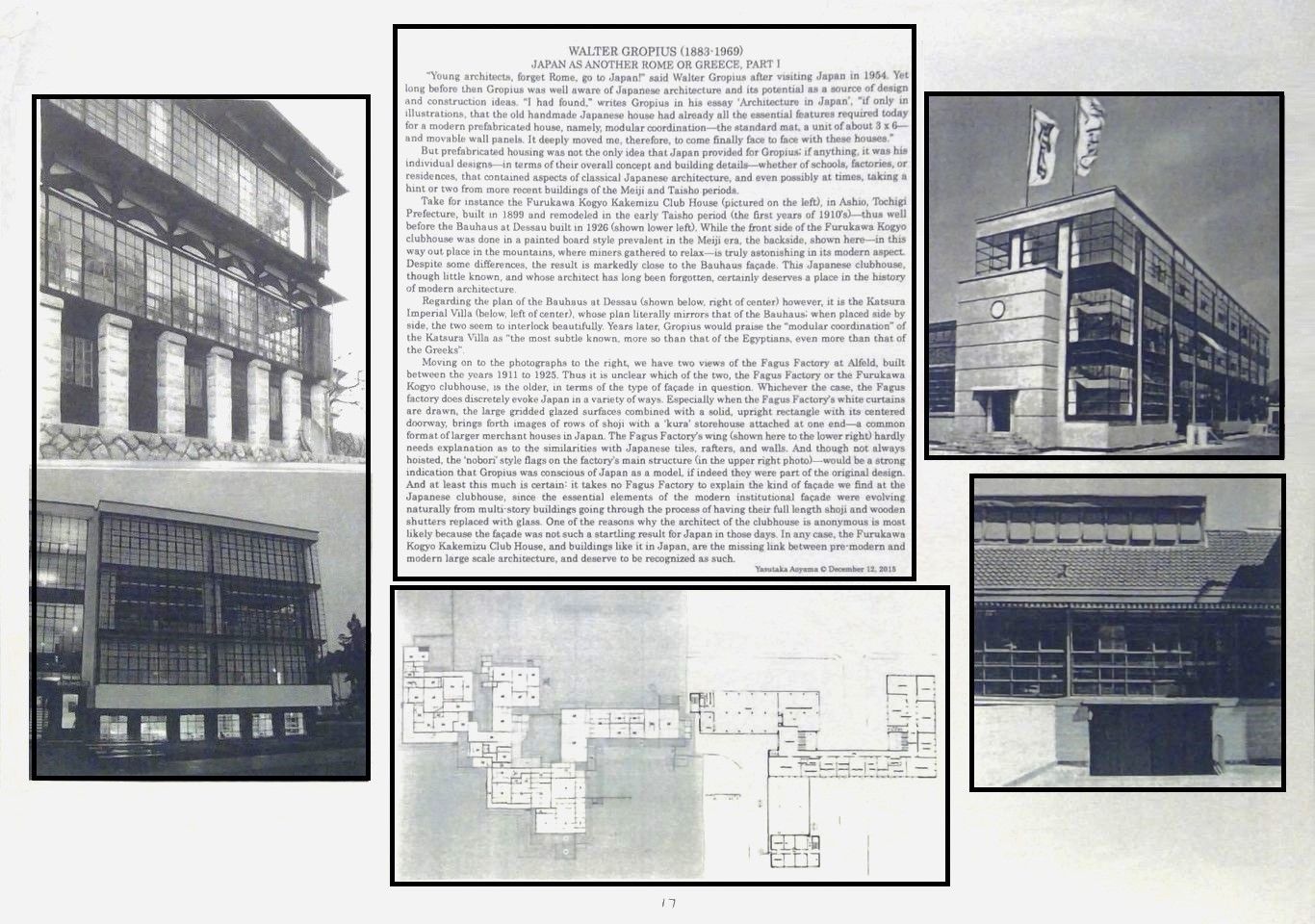

Walter Gropius (1883-1969)

Japan as Another Rome (or Greece), Part I

Lecture handout 2015.12.12, Architectural Juxtapositions, p.17

Yasutaka Aoyama

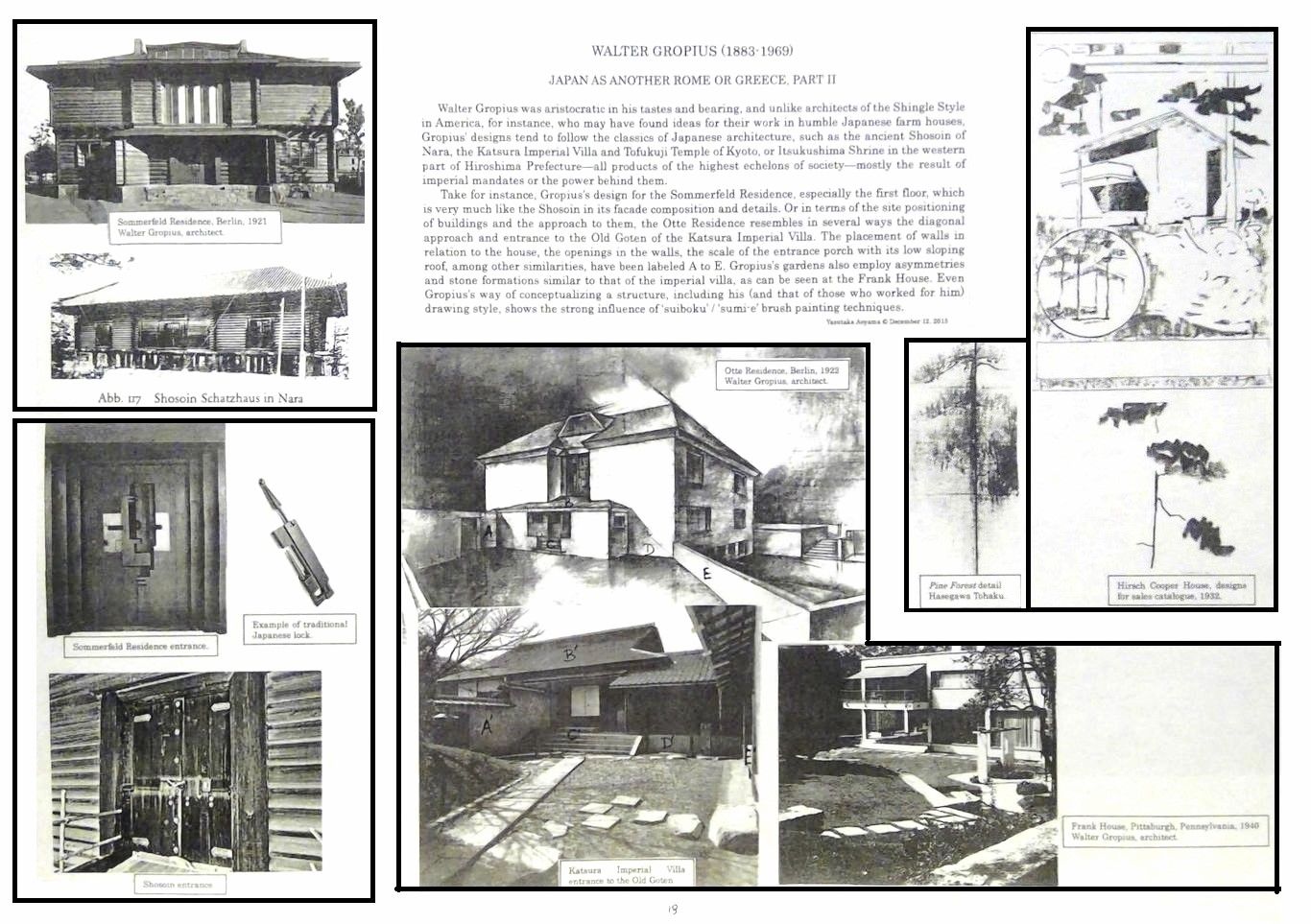

Walter Gropius

Japan as Another Rome (or Greece), Part II

Lecture handout 2015.12.12, Architectural Juxtapositions, p.18

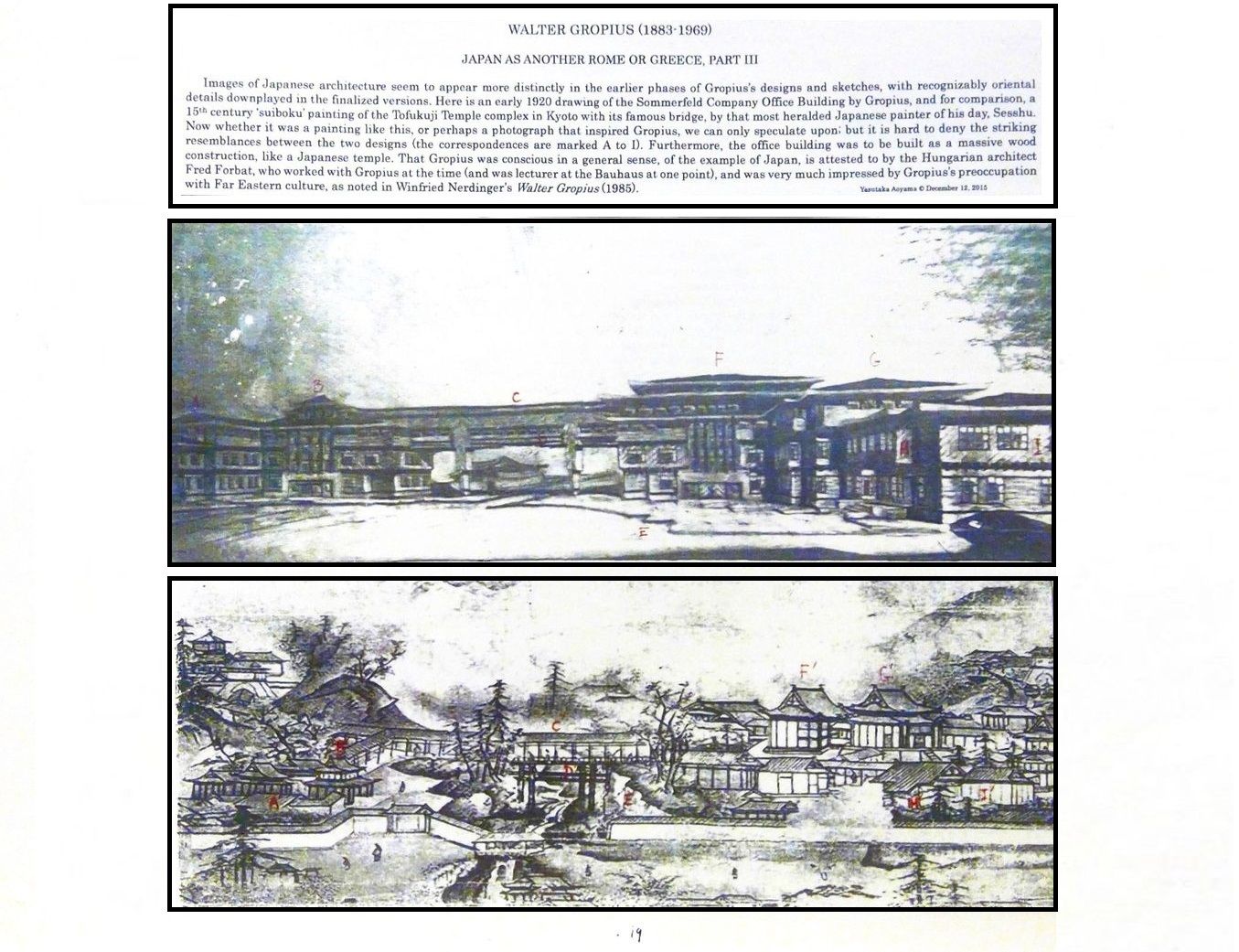

Walter Gropius

Japan as Another Rome (or Greece), Part III

Lecture handout 2015.12.12, Architectural Juxtapositions, p.19

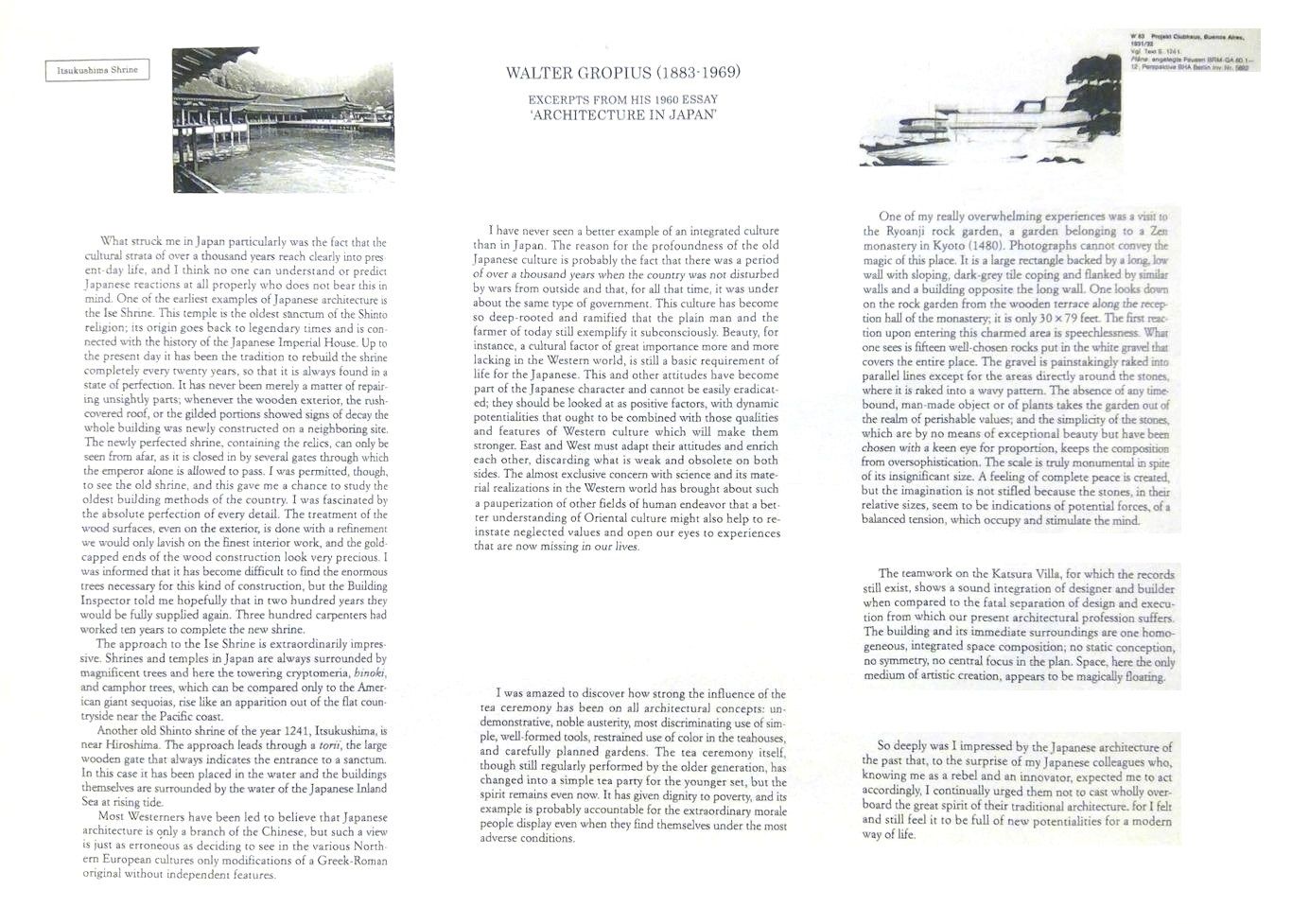

Walter Gropius

Excerpts from his essay 'Architecture in Japan'

Additional class reading material, Kyoto University, 2015.12.12

Walter Gropius

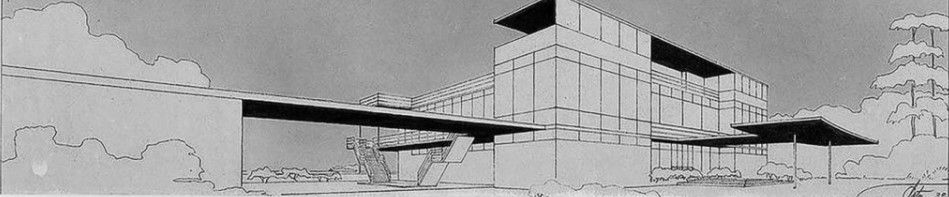

Japan as another Rome (or Greece), Part IV

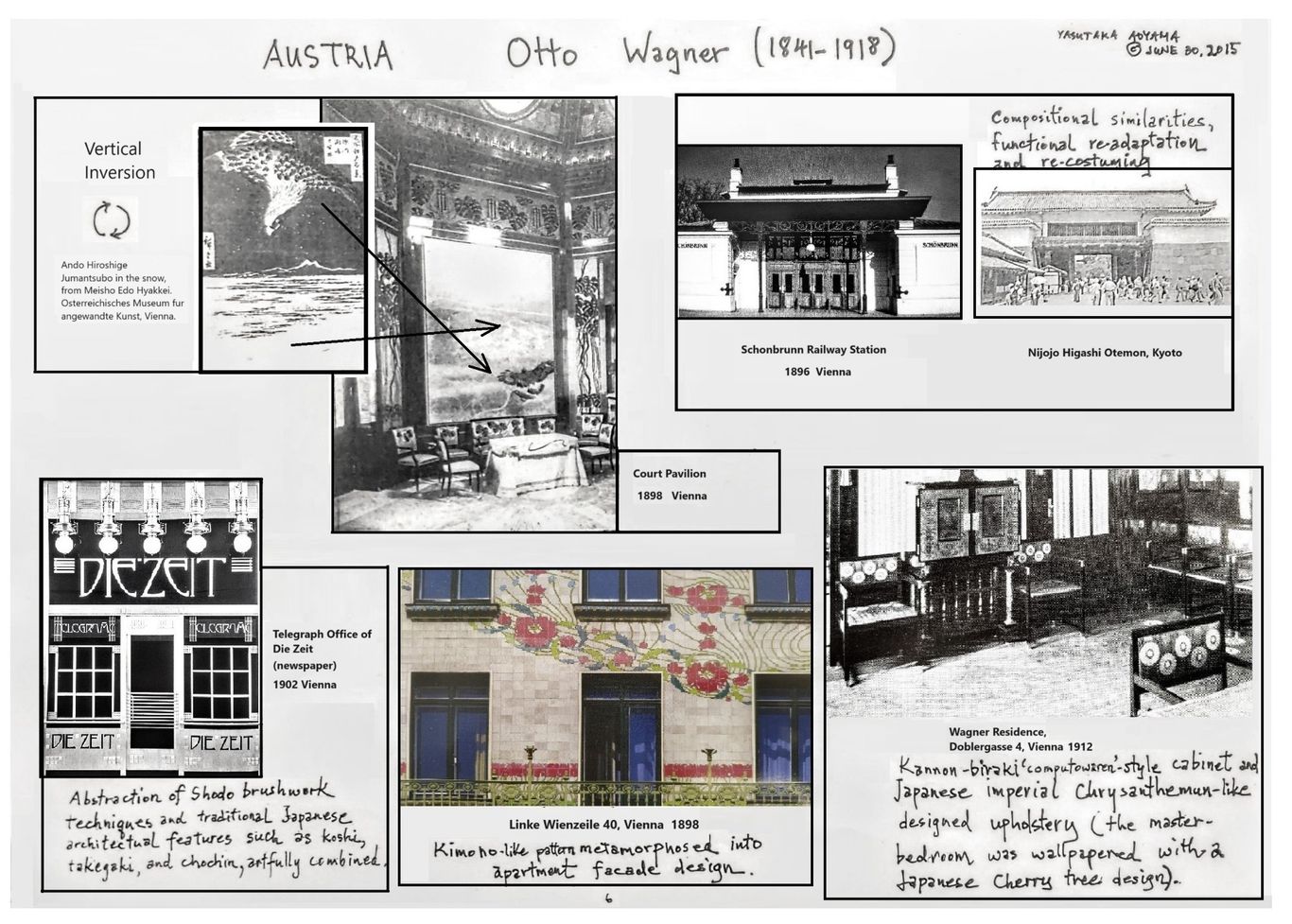

Project Clubhouse, Buenos Aires, Argentina (1931–1932)

Originally uploaded 2023, revised 2024.5.31

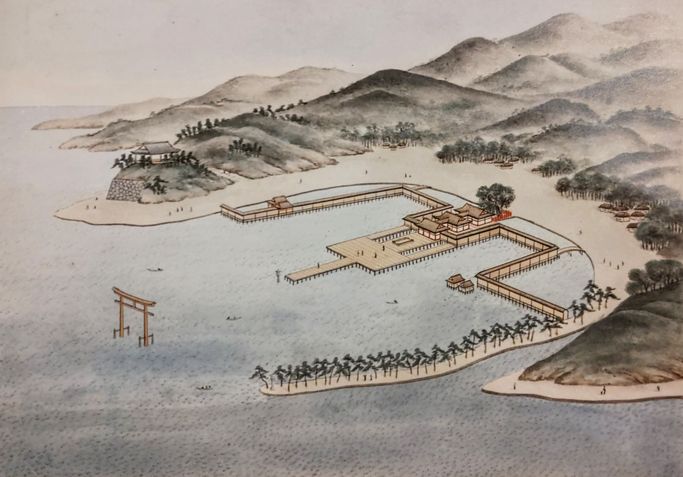

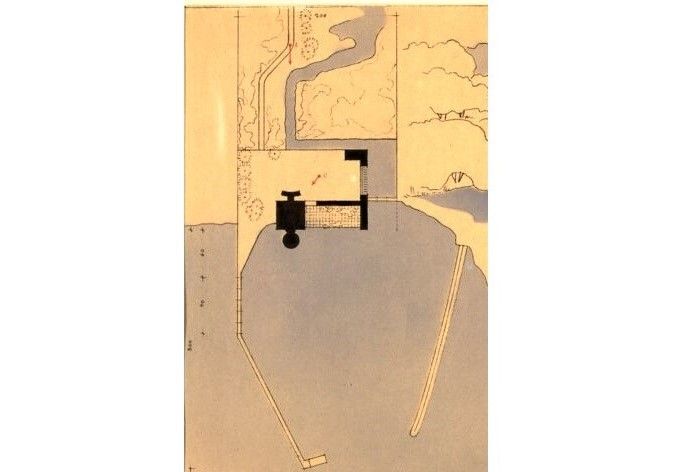

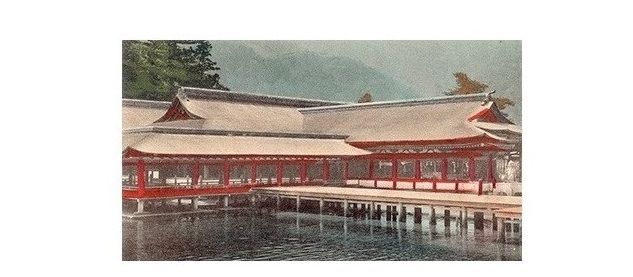

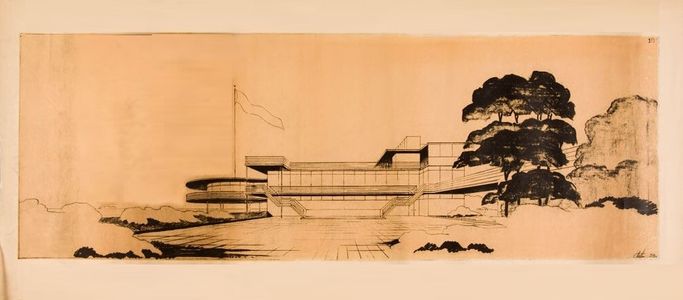

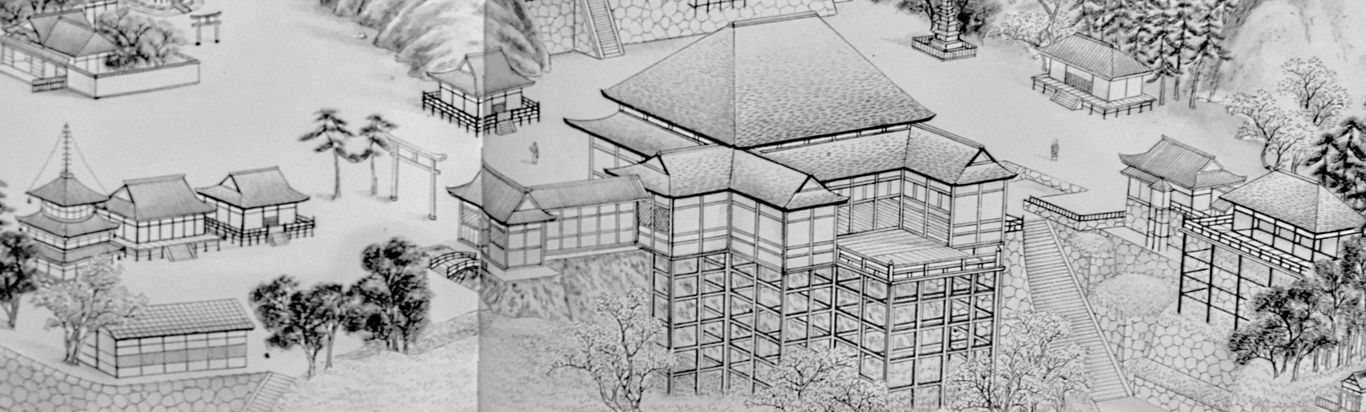

Above: Walter Gropius (with Hanns Dustmann and Franz Möller), Project Clubhouse sketch, for a Buenos Aires resort, with Japanesque gridded geometric facades, thin and long extending wings along or out onto the water, and curved, extending roofs. Japanese architecture, when sketched in outline form, often yields similar impressions, as with the example of by Kawahara Keiga of Kiyomizu-dera Temple, shown below.

Kawahara Keiga, Kiyozumi-dera, Siebold Collection

Gropius' sketches of the Buenos Aires Clubhouse project---the concepts contained within the plans and elevations echo in various ways the architectonics of Itsukushima Shrine, Hiroshima Prefecture, including a monument placed far out in the water, for viewing from the building.

Photos from Tokyo National Museum et al., Von Siebold and Japan (1988) and Harvard Art Museums, 'Displaying Latin America' (2019).

________________________

Johannes Itten (1888-1967)

of the Bauhaus

Japan in his Art and Pedagogy, Part I

Lecture handout 2016.1.7, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 20

Yasutaka Aoyama

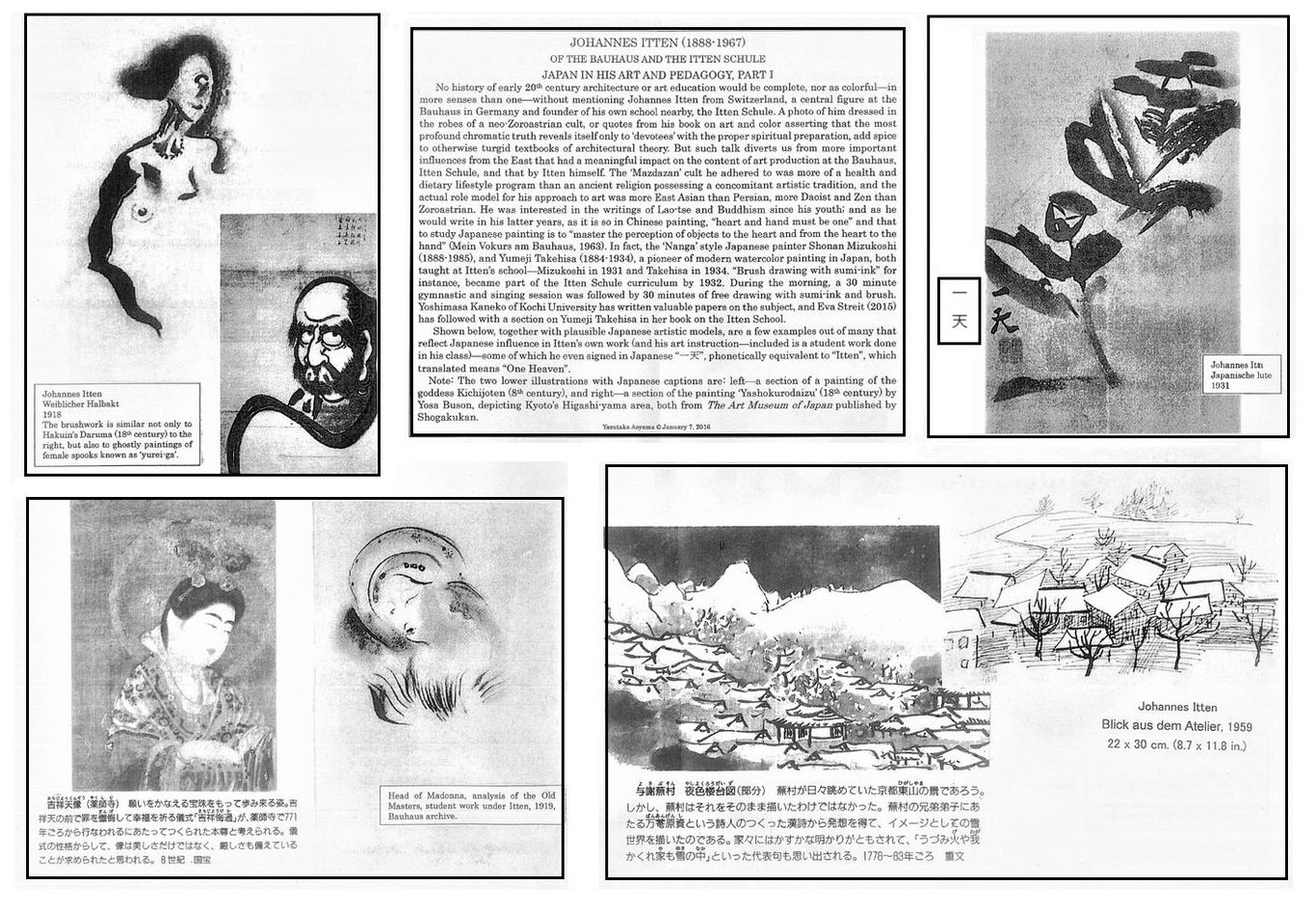

No history of early 20th century architecture or art education be complete, nor as colorful in more senses than one---without mentioning Johannes Itten from Switzerland, a central figure at the Bauhaus in Germany, and founder of his own school nearby, the Itten Schule. A photo of him dressed in the robes of a neo-Zoroastrian cult, or quotes from his book on art and color asserting that the most profound chromatic truth reveals itself only to 'devotees' wth the proper spiritual preparation, add spice to otherwise turgid textbooks of architectural theory.

But such talk diverts us from more important influences from the East that had a meaningful impact on the content of art production at the Bauhaus, at the Itten Schule, and that by Itten himself. The 'Mazdazan' cult he adhered to was more of a health and dietary lifestyle program than an ancient religion possessing a concomitant artistic tradition, and the actual role model for his approach to art was more East Asian than Persian, more Daoist and Zen than Zoroastrian. He was interested in the writings of Lao-tse and Buddhism since his youth; and as he would write in his latter years, as it it is so in Chinese painting, "heart and hand must be one" and that to study Japanese panting is to "master the perception of objects to the heart and from the heart to the hand" (Mein Vokurs am Bauhaus, 1963). In fact, the Nanga style Japanese painter Shonan Mizukoshi and Yumeiji Takehisa, a pioneer of modern watercolor painting in Japan, both taught at Itten's school---Mizukoshi in 1931 and Takehisa in 1934. "Brush drawing with sumi-ink" for instance, became part of the Itten Schule curriculum by 1932. During the morning, a 30 minute gymnastic and singing session, (reminiscent too of 20th century Japanese custom), was followed by 30 minutes of free drawing with sumi-ink and brush. Yoshimasa Kaneko of Kochi University has written valuable papers on the subject, and Eva Streit (2015) has followed with a section on Yumeji in her book on the Itten School.

Shown below, together with plausible Japanese artistic models, are a few examples out of many that reflect Japanese influence in Itten's own work (and his art instruction, included is a student work done in his class)---some of which he even signed in Japanese "一天", phonettically equivalent to "Itten", which translated means "One Heaven".

Note: The two lower illustrations with Japanese captions are: left, a section of a painting of the goddess Kichijoten (8th century), and right, a section of the painting 'Yashokurodaizu' (18th century) by Yosa Buson, depicting Kyoto's Higashi-yama area, both from the The Art Museum of Japan published by Shogakukan.

Johannes Itten

Japan in his Art and Pedagogy, Part II

Lecture handout 2016.1.7, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 21

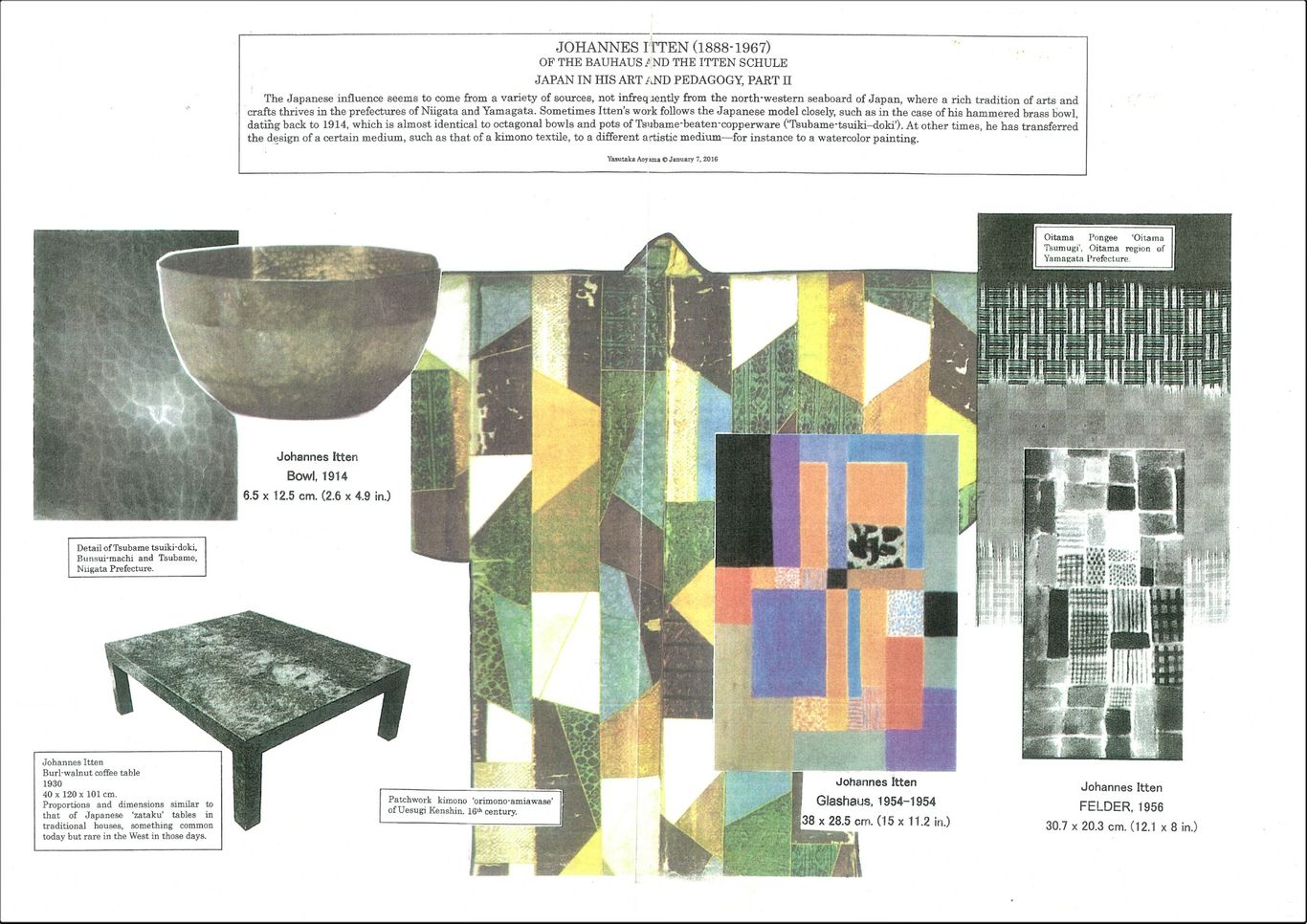

The Japanese influence seems to come from a variety of sources, not infrequently from the north-western seaboard of Japan, where a rich tradtion of arts and crafts thrives in the prefectures of Niigata and Yamagata. Sometimes Itten's work follows the Japanese model closely, such as in the case of his hammered brass bowl, dating back to 1914, which is almost identical to octagonal bowls and pots of Tsubame beaten copperware ('Tsubame-tsuiki doki'). At other times, he has transferred the design of a certain medium, such as that of a kimono textile, to a different artistic medium---for instance, to a watercolor painting.

An article on the Bauhaus and Japan: Keshav Anand, 'How Japan’s Imperial Architecture Influenced The Bauhaus', Something Curated at somethingcurated.com. Visited May, 2024.

________________________

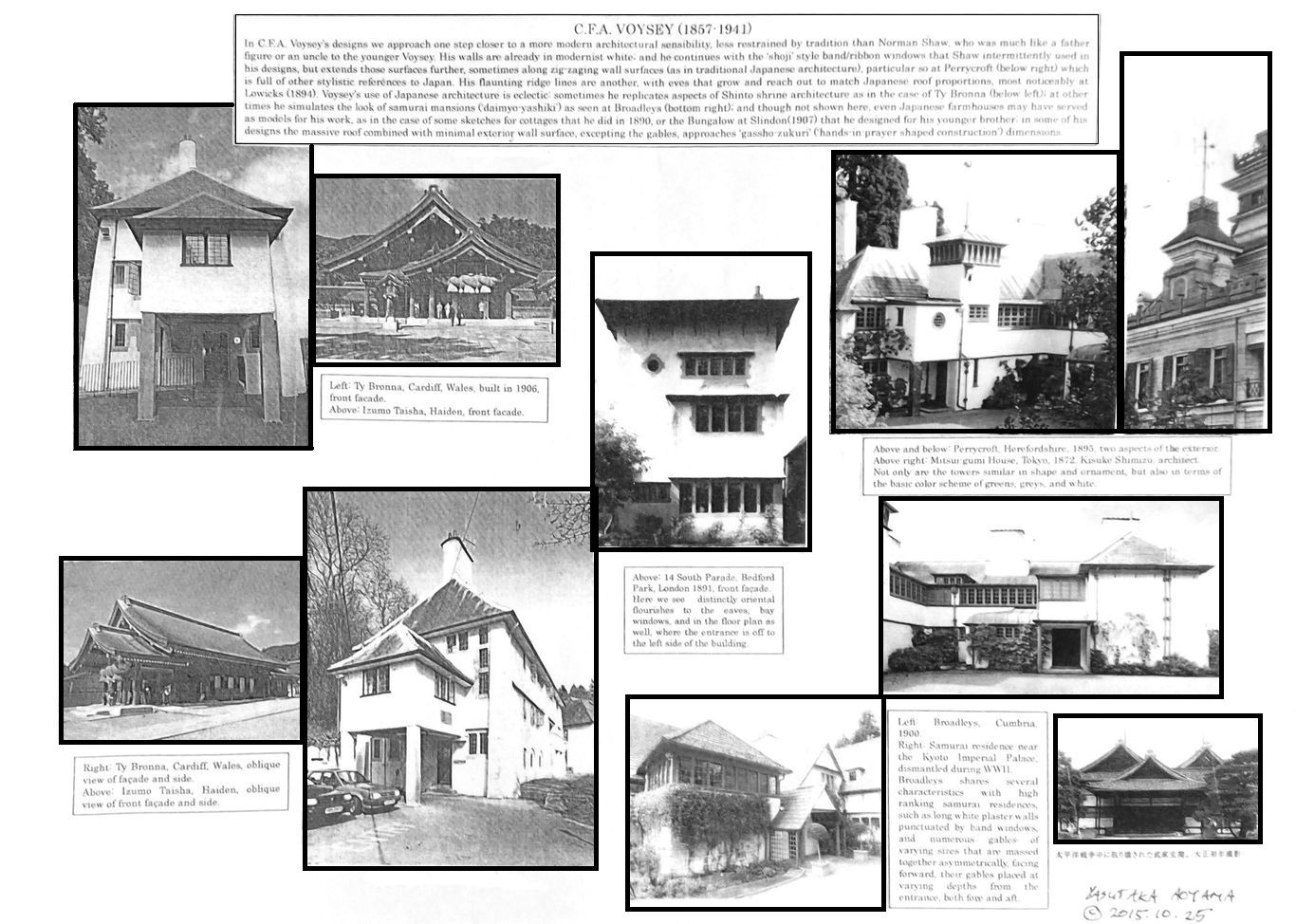

C. F. A. Voysey (1857-1941)

Part I: Exteriors

Perhaps Best Described as a 'Tibeto-Japanese' Melange

Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 22

Yasutaka Aoyama

Voysey's creative sources have not been sufficiently investigated. While his interiors can be evaluated within the context of the general trend of japonisme, his exteriors, while exhibiting elements of Japanese architecture, also exhibit commonalities with Tibetan, or more widely, Himalayan architectural forms, available, for instance, in the 1783 paintings of Bhutan dzongs by Samuel Davis.

The Tibeto-Bhutan parallels aside, circumstances and relationships of Voysey point to a link with Japanese art. For instance, Voysey, on the recommendation of his friend Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo (known for his involvement with Japanese interiors most notably that of the Mortimer Mempes House discussed later in this section), tried his hand at designing wallpaper, carpets, and textile designs, often using motifs which were very likely taken from katagami designs, an example of which is shown in Katagami Style (2012, supervised by Mabuchi Akiko, Director of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo) of a poppy flower motif for a decorative fabric (c. 1894, exhibit #2033). The 1890's was a time when publications on Japanese design became readily available, and the astonishing diversity and dramatic visual impact of katagami attracted designers in all fields, including architects.

The following added 2024.9.14

Robert Schmutzler, a leading historian of Art Nouveau in the English-speaking world, in his classic Art Nouveau (1962,1977), after commenting on how Voysey was influenced by Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo, writes:

“However, for Voysey as an architect, Japanese influences were perhaps even more important, though they are scarcely recognizable as such in his work. One of his most interesting works, the tower-like house in Bedford Park [shown below, center] that he finished in 1891, is an exception. The light roof with its low gradient, the concave curved roofing of the oriels, the thin metal supports that seem to raise the roof over the body of the building, the unusually small windows, and the one stressed bull’s-eye window are not outright Japanese forms; but the graphic, abstractly ornamental, and asymmetrical character of the surfaces, the contrast in black and white between the apertures and the white-washed walls, not to mention the frieze-like disposition of various groups of windows under the thin horizontal ledges, all clearly reveal the relationship to Japanese architecture, easily recalling Japanese teahouses and small temples, as for example Voysey’s similar but lower and longer country houses, which are a particular national achievement of English art.” ---Schmutzler, Art Nouveau, 1977 abridged edition, pp. 128-9.

Yet we should add that those elements which Schmutzler categorizes as not obviously Japanese forms, as a low gradient roof, concave curved roofing, thin supports that raise the roof over the body of the building; or the bull’s-eye window---are in fact common features of traditional Japanese architecture, though not necessarily found together in one building. Even the small windows could be considered so, if we think of Japanese castle architecture. Indeed, the whole structure resembles a Japanese castle in various respects, including the frieze-like disposition of various groups of windows under the horizontal ledges, the white washed walls and their thick appearing aspect, and the contrast of black and white, though this is shared with Tibetan and Bhutanese architecture as well.

As to which inspired Voysey, Japan or Tibet/Bhutan in this case, either or both are possible; but as so much of his other architectural work reflects Japanese elements, both in his exteriors and interiors, as well as in his other designs, with hints such as “Tokyo” (wallpaper, 1893), the former seems more likely. Furthermore, models of Japanese castles were exhibited in Britain and on the Continent in world expositions and privately collected, and paintings and prints of castles abounded in England by the time of Voysey’s designing the Bedford Park house. On the other hand, Tibetan/Bhutanese models were scarcer though existing in sketches and paintings by a few, but we would not like to close the door on the possibility. It is an intriguing parallel, and at the very least it deserves mention as enriching our global perspective on modern architecture, even if there is no causative connection.

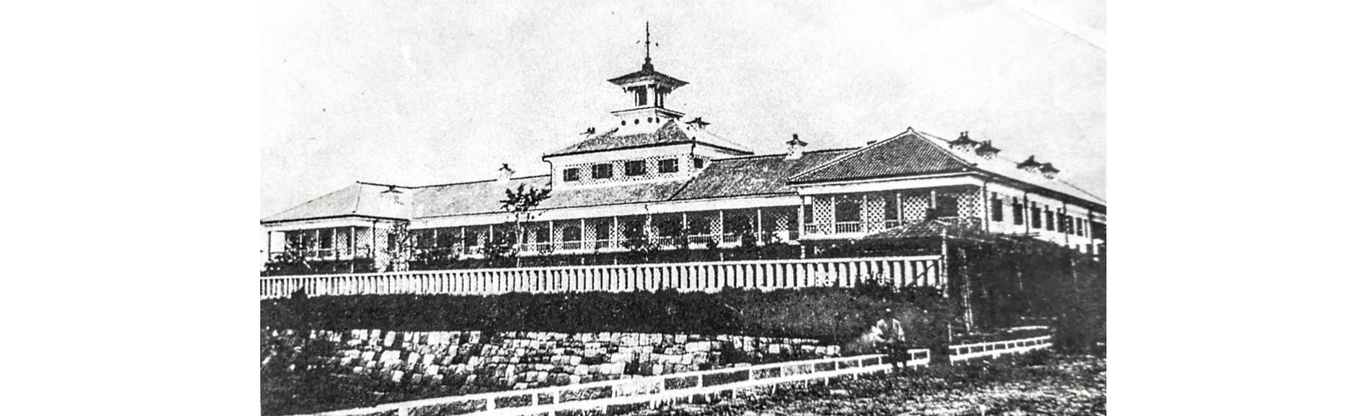

Below: An example of early Meiji era architecture, the Tsukiji Hotel, Tokyo, 1868. This was a hotel built for Western visitors. There are aspects of its design reminiscent of Voysey. Novel architectural forms were being produced in abundance in Japan from the late 1860's onward to the early 20th century, that precede the appearance of similar forms in the West. It might be said that much of the reputation for originality of certain architects in Europe or America in those days depends on an ignorance of the building activity going on in Japan at the time.

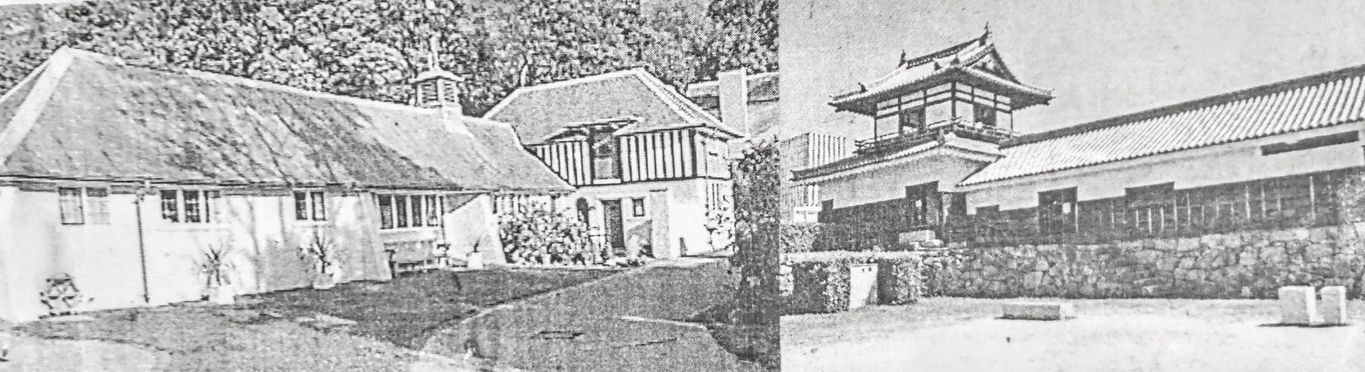

Below: Photos pasted side by side from the author's scrapbook, on the left is a Voysey designed house, on the right a Japanese castle 'yagura' (a corner tower and storehouse/sentinel quarters combination). Despite obvious differences, there is an affinity of general conceptualizations between Japan's and Voyseys' architecture.

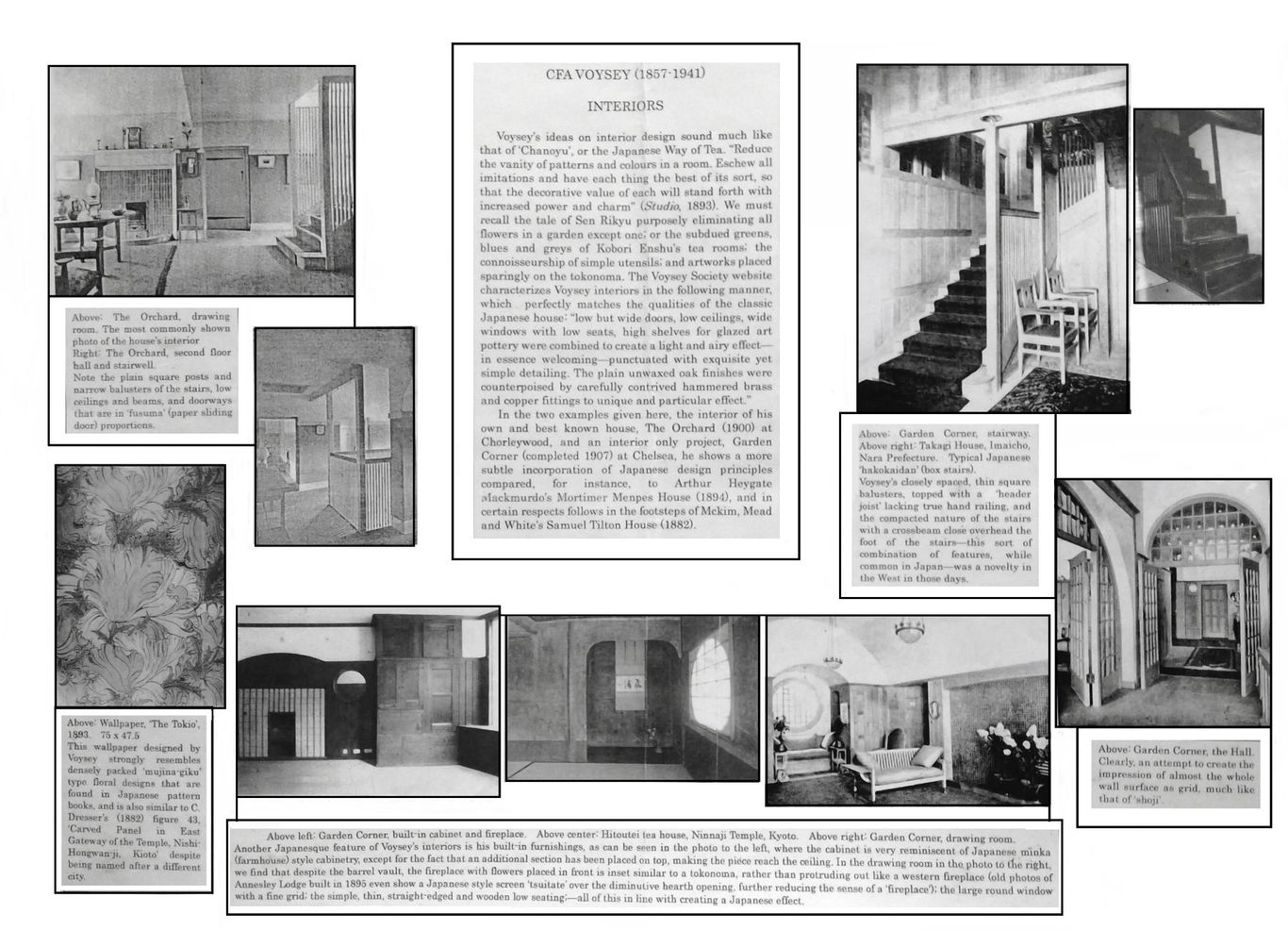

C. F. A. Voysey (1857-1941)

Part II: Interiors

Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 23

________________________

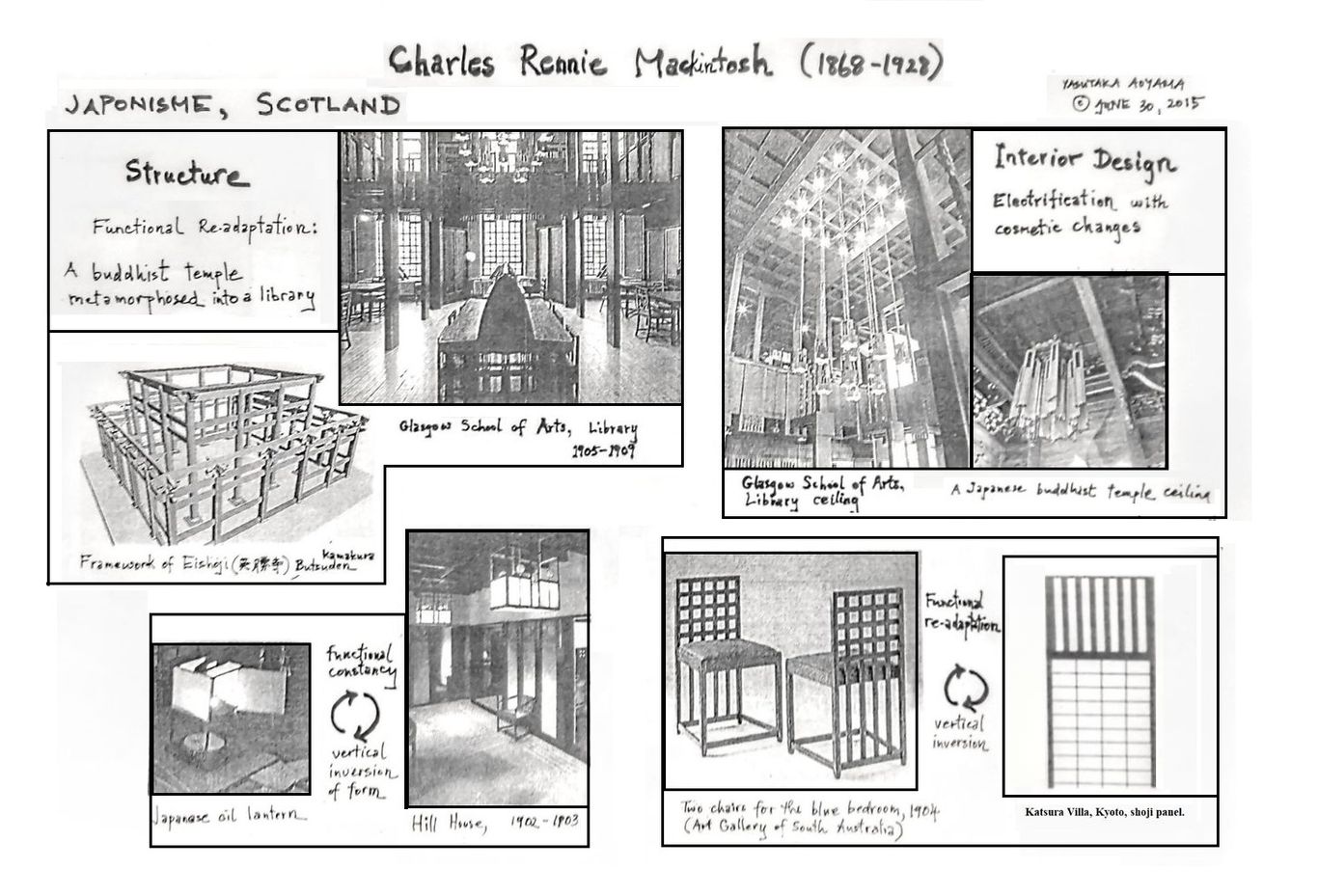

Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928)

Part I: Functional Readaptations of Japanese Designs

(with Observations on an Interior by Sir William Reynolds-Stephens)

Lecture handout, scrapbook form 2015.6.30, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 40, note on Reynolds-Stephens added 2024.9.17

Yasutaka Aoyama

"To those with eyes to see, however, and especially to Mackintosh, the Japanese house presented a new challenge. Could the delightful freedom and spaciousness of the open plan be translated into Western terms; could its remarkable flexibility and exciting aesthetic potentialities be exploited under the climatic conditions prevailing here? These questions Mackintosh attempted to answer in his own way by the use of openwork screens, balconies, and square post and lintel construction. The influence of Japan is evident throughout his work, especially in the Cranston Tea-Rooms, and in the library at the Glasgow School of Art--even the boldly cantilevered galleries of Queen's Cross Church have at least one counterpart in the Far East, the balcony of an old inn at Mishima, illustrated by Morse."

Thomas Howarth, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, p. 225.

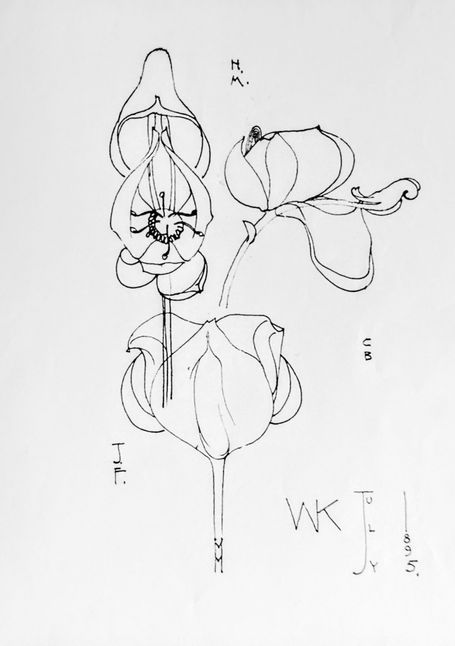

Mackintosh's first major biographer, Thomas Howarth, pointed out early on in his 1952 award-winning book, Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Modern Movement, the importance of Japan as an artistic influence on Mackintosh (see also Andrew MacMillan, 'Charles Rennie Mackintosh: A Mainstream Forerunner' Architectural Association Quarterly, vol. 12 no.3, 1980). There are many aspects of Mackintosh's Hill House, as well as his other creations such as the Willow Tea Rooms and his 78 Derngate house, that reveal an eclectic array of Japanese motifs. Those influences range from the kimono (e.g. his well-known 'kimono cabinet') and ikebana flower arrangement, to Buddhist temple design and ornament. Even his watercolor botanical sketches are reminiscent of sumi-ink painting, and are at times signed in a vertical, oriental fashion, with the words framed (boxed in) as in Japanese prints (e.g. his sketch 'Japonica'). That Mackintosh had an interest in Japanese art from his early days can be gleaned in a circa 1890 photo of Mackintosh's studio bedroom at Dennistoun, Glasgow, where an unidentified ukiyo-e print can be made out above the mantlepiece, though the Japanese lettering is indiscernible. Glasgow's relationship with Japan was closer than most might think in those years, thanks to the shipyards at the River Clyde where there was much contact with those related to shipbuilding, such as Japanese navy engineers.

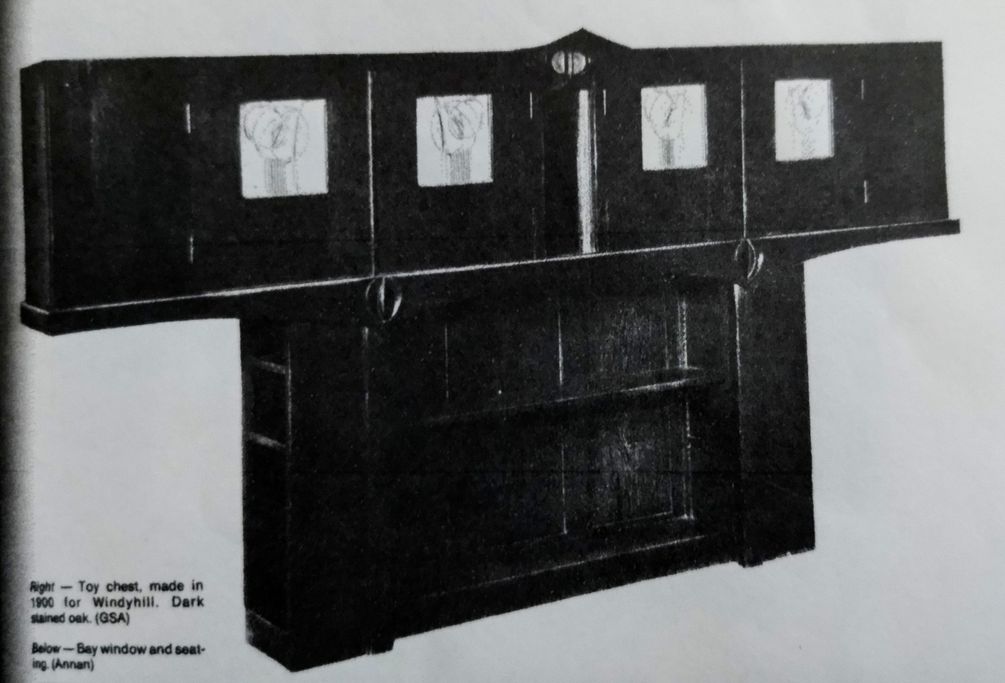

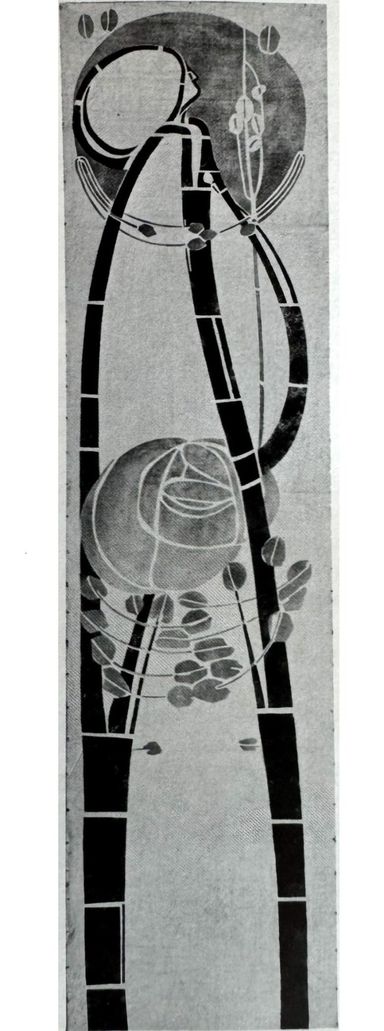

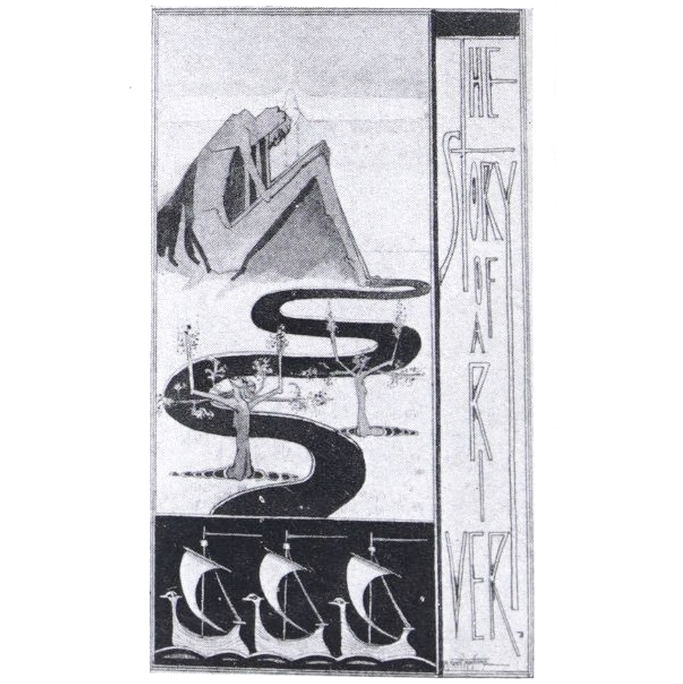

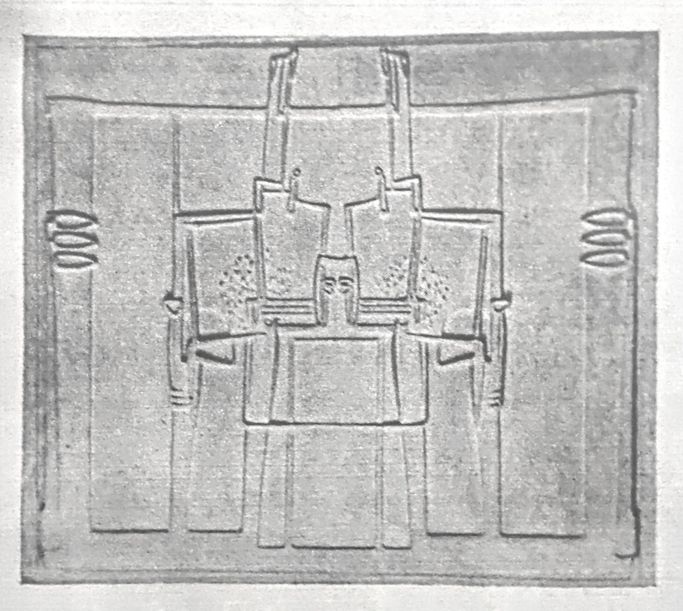

Below are some examples of Mackintosh's 'functional re-adaptations' of Japanese, especially Buddhist, architecture and ornament. A temple for instance becomes a library or a shoji window the back rest of a chair, for instance.

Below left: the Willow Tea Rooms, first two floors. Right: typical Japanese merchant house of the Edo period, with the 2nd floor walls in white with the quintessentially Japanese grilled window and first floor in dark wood, also with continuous windows with the lower half cut out towards the end.

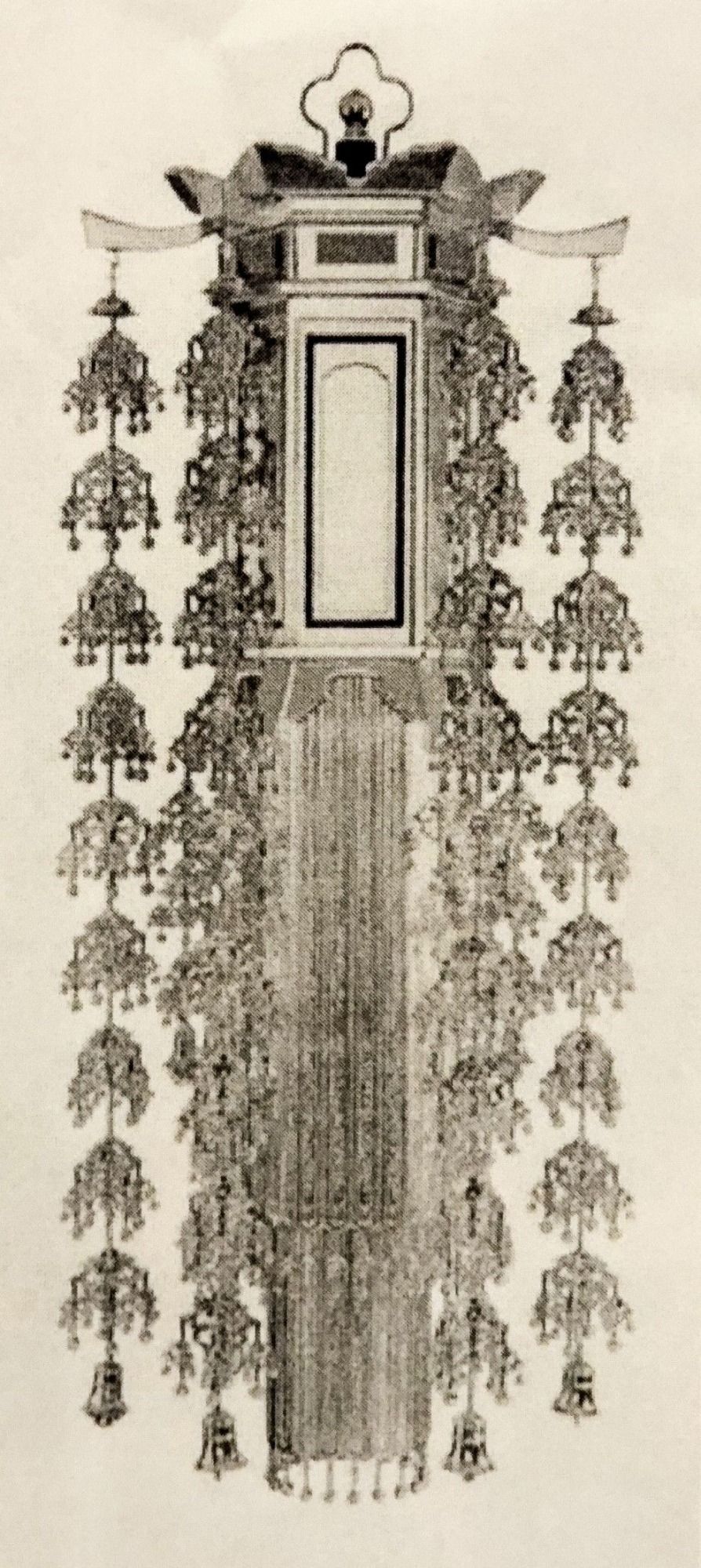

Below: Comparisons of various aspects of Mackintosh's interiors and exterior decor to the left, vis-a-vis elements of Japanese Buddhist temples and other buddhist paraphernalia to the right. Note the prominent use of black lacquer furnishings and hanging golden ceiling ornaments, and white silk panels or white plaster walls, abstracted in Mackintosh's 78 Derngate, Northhampton house, but still recognizable. These are but a few examples; not shown for instance, is a comparison of the large metal, somewhat bean-shaped ornaments that hang from Jodoshinshu sect temples of which an almost exact duplicate existed in Mackintosh's Willow Tea Rooms.

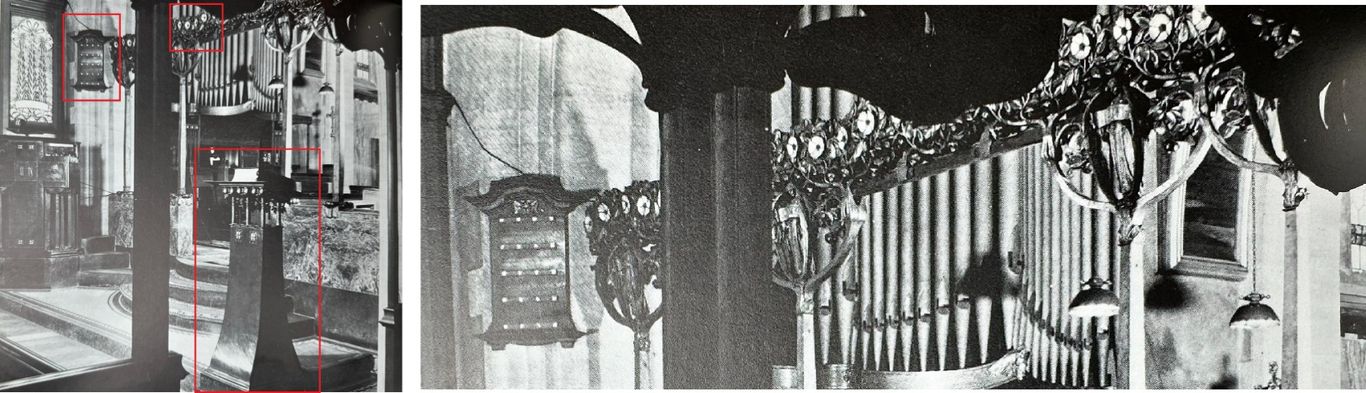

We might note as an aside that the interest in Japanese religious architecture was not limited to Mackintosh. Echoes of sacred Japanese architectural elements are found early on in the American Stick Style, discussed earlier, as well as elsewhere in Britain in Mackintosh's time. A good example is William Reynolds-Stephens' (1862-1942) design for the interior of St. Mary the Virgin, Great Warley, Essex (1904), shown below, which was completed just before the building of Mackintosh's Glasgow School of Arts Library (1905-1909). The elements blocked in red reflect various aspects of Buddhist temple or Shinto shrine structures and ornament.

In the foreground of the picture to the left is a minature tower-like structure, which looks as if made of metal, whose form is much like that of a temple or shrine 'toro' (stone or wood lantern). To the right is a close up of the upper part of the photograph (from R. Schmutzler, Art Nouveau, 1977). In it is a hanging, roofed, plaque-like object much like a 'zushi' (minature, portable reliquary) in form, and to the right of it running horizontally is a metal ornament with a floral design, reminiscent of temple or shrine eave decorations.

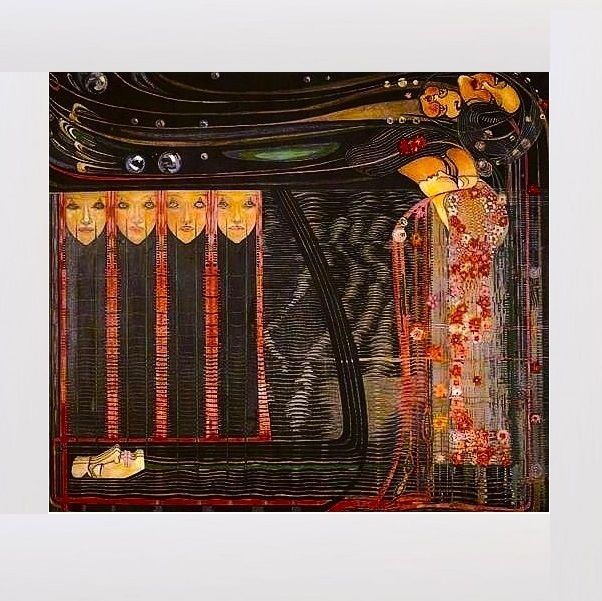

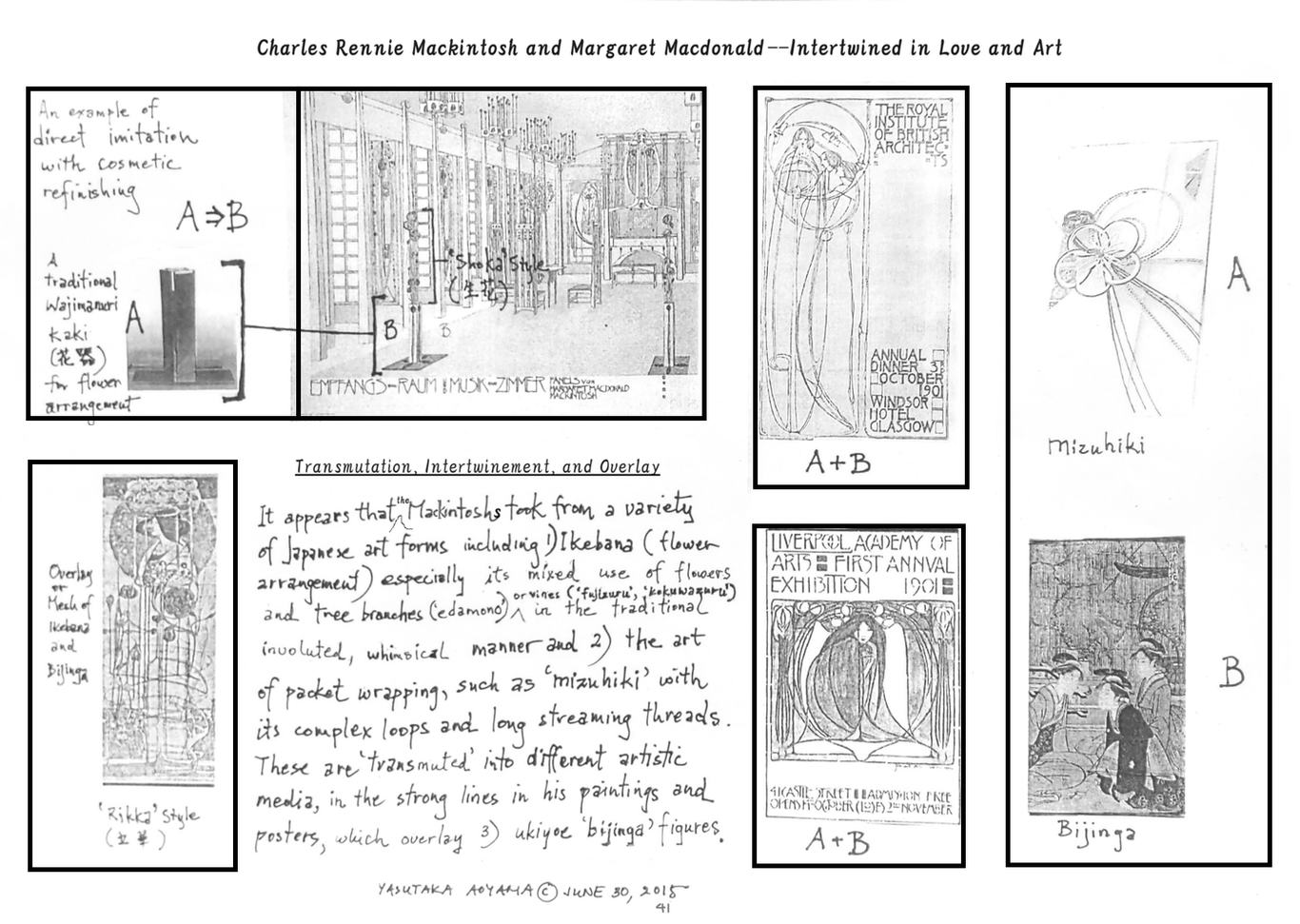

Charles Rennie Mackintosh & Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh

Part II: Transmutation, Intertwinement, and Overlay

Lecture handout, scapebook format, 2015.6.30, Architectural Juxtapositions, p. 41

Revisions, editing, and added commentary 2023.9.16 -28

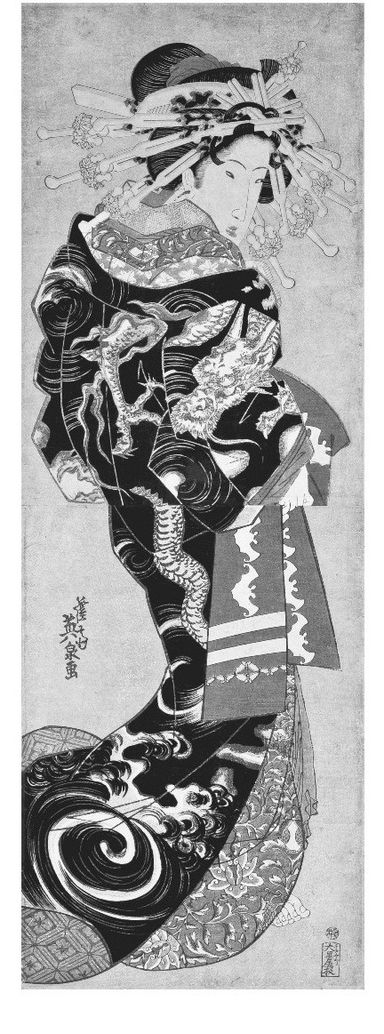

It appears that the Mackintoshs took inspiration from a variety of Japanese art forms including ukiyo-e bijin-ga (pictures of beautiful women, often courtesans), sumi-e (charcoal painting) or suiboku-ga (landscape ink wash painting), and ikebana flower arrangement, especially its mixed use of flowers and edamono (tree branches) or tsuru (vines, e.g. fujizuru or kokuwazuru) in the traditional Japanese convoluted and whimsical manner. They may also have discovered the Japanese art of packet wrapping and decorative tying known as mizuhiki with its complex loops and long streaming threads. These sources were combined and 'transmuted' into art of different media, namely paintings and sculptures, their forms reflected in the strong and multitidinous lines found in their works, those lines often overlaid or fused with bijinga type figures.

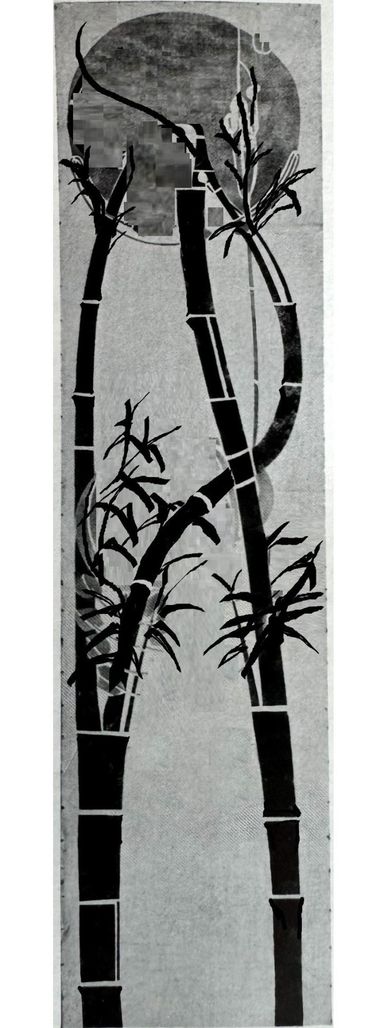

The following is an attempt to illustrate the idea, taking a decorative wall hanging (1902) by Charles Rennie Mackintosh as an example, on the right. On the left is the ukiyo-e print 'Unryu Uchikake no Oiran' by Keisai Eisen (1790-1848), the courtesan print that Van Gogh modeled his painting 'The Courtesan' upon. She is in a classic ukiyo-e pose, depicting a female figure in flowing robes with her hair bunched up in the back, poised in a way where she is somewhat sideways with her shoulder accented, jutting towards us, her face at an angle partially hidden.

In the center, this author has taken the liberty of creating a quick, kakejiku (hanging scroll) type painting using Mackintosh's picture, making some modifications but relying very much on Mackintosh's original design. More bamboo twigs and leaves are needed, but enough is there to show how close Mackintosh's wall hanging is to sumi-e hanging scroll compositions, including aspects of detail (as the bamboo segmenting or leaves silhouetted by the moon). It seems highly probable that Mackintosh was inspired by sumi-e / suiboku-ga scroll imagery depicting bamboo in moonlight, a common motif in that type of painting. In Mackintosh's picture the bamboo trunks have become outlines of the woman's robe-like dress; a large rose or other flower-like shape sits where usually a mass of bamboo leaves would typically be painted; or otherwise where the bold, focal element of a kimono or uchikake (long overgarment) might be displayed in a bijinga---in Eisen's print it is the face of a dragon, but a large flower or other round shape would not be uncommon.

It is not difficult to see how Mackintosh's image is an amalgamation and entwining, or otherwise an overlaying of imagery, to create something new, which draws from the artistry and emotional content of those very disparate artworks.

Though barely discernable in the bijinga image above (bottom right corner), in the background of the three women is a ikebana display of curving, interwined branches. In Japan flower arrangements have traditionally incorporated the branches, twigs, vines, and leafs of plants much more so than in the West (where flower arrangement until then was basically making a bouquets of flowers) and it was this more primal, vegetative aspect that must have caught the attention of the Mackintoshes, and the complex and convoluted formations that were actively pursued by ikebana artists.

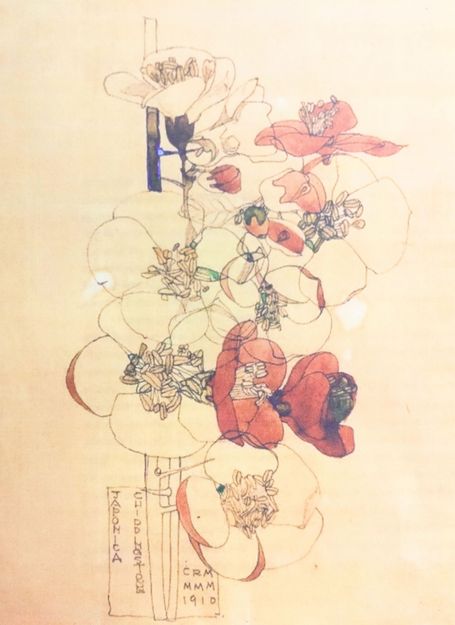

Below: left--his watercolor 'Japonica'; center--a sketch signed a labeled horizontally in Japanese fashion; right--a juxtaposition of a Mackintosh sketch and a Japanese traditional sketch of lilies.

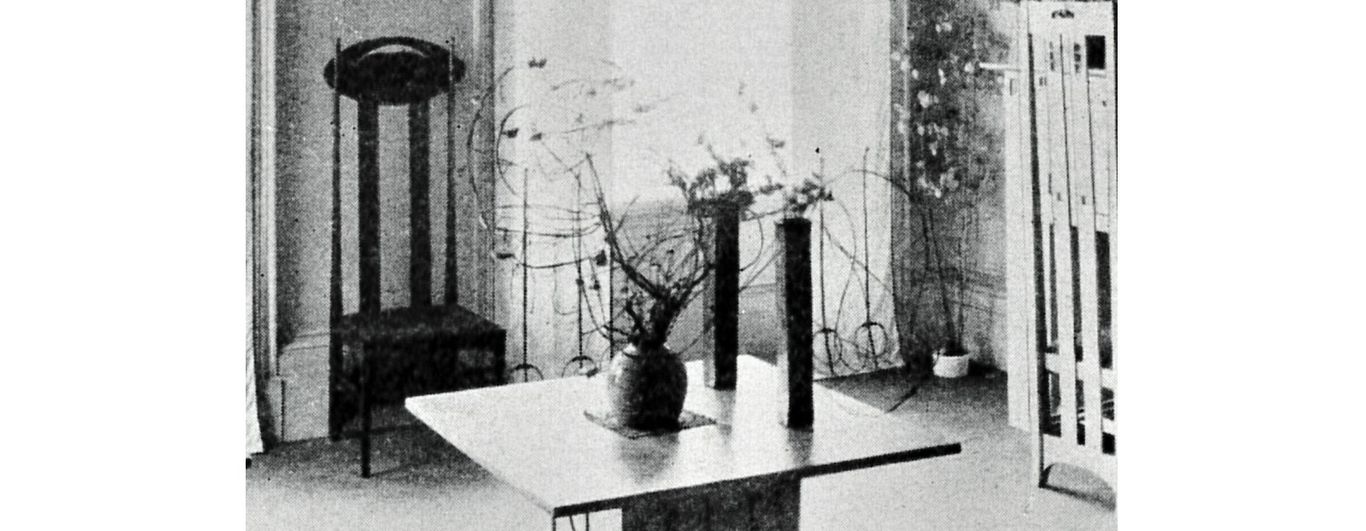

Living with ikebana

It seems ikebana was a heartfelt passion for the Mackintoshes, and not just a device for designs. The Mackintosh studio flat, 120 Mains Street, Glasgow (1900) was overflowing with multiple ikebana-type flower arrangements it seems, as captured in the photo below (from Howarth, 1952). Note the tall, rectangular 'kaki' (flower arrangement container) style vases, peculiar to ikebana in Japan. On the mantlepiece, not visible here, were ukiyo-e prints (See Erin McQuarrie, 'Ma, Mon, Tori-i: The Influence of Japanese art and design on Charles Rennie Mackintosh's masterwork, The Glasgow School of Art'. Glasgow School of Art dissertation.)

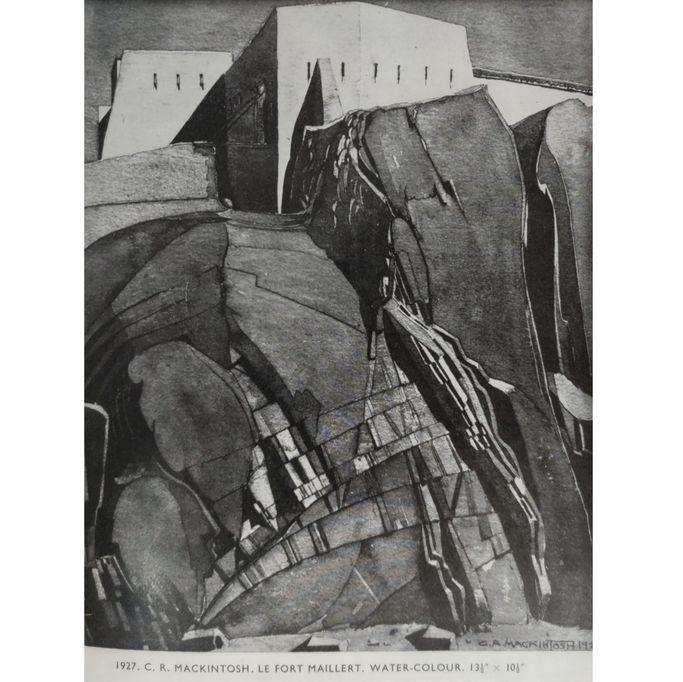

The influence of suiboku-ga, or Chinese style ink wash painting in Mackintosh

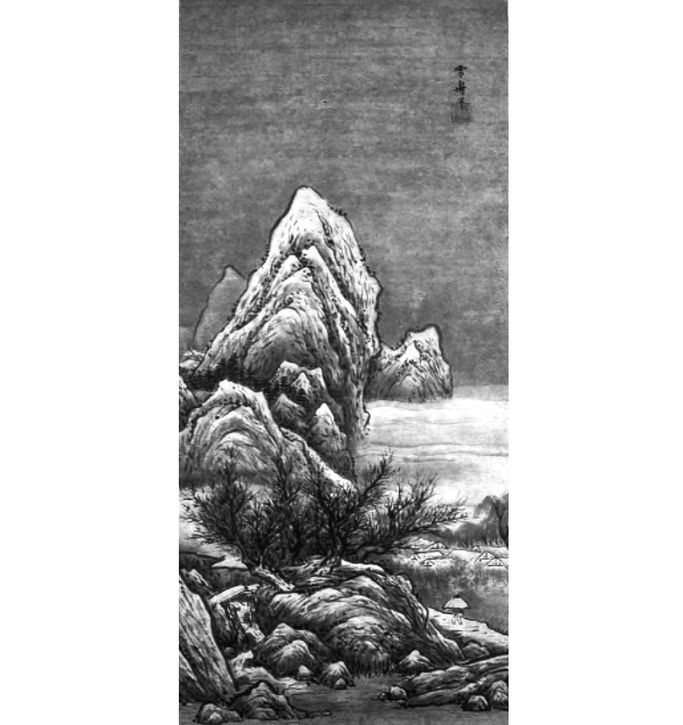

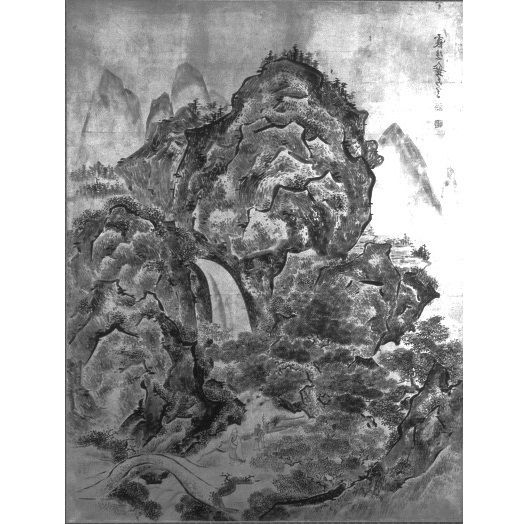

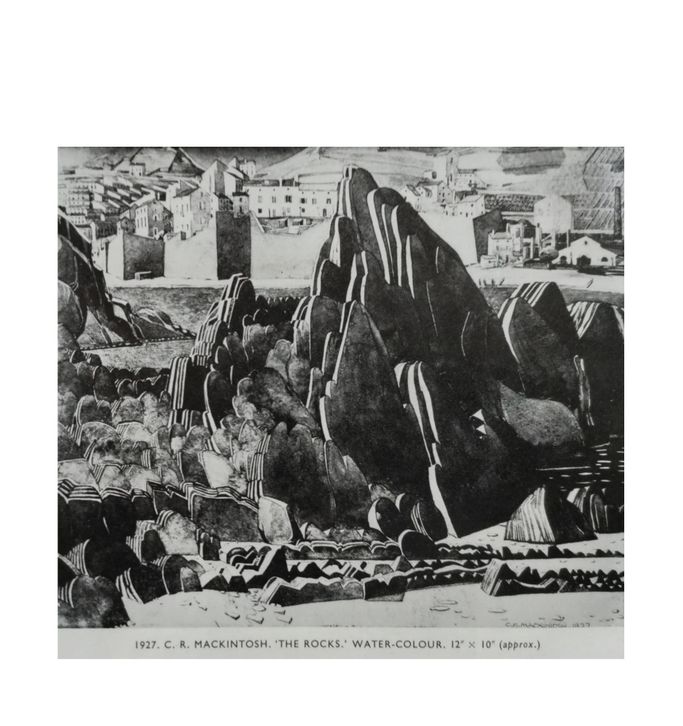

Below: 1) Sesshu, 'Winter Landscape',15th century (Univ. of Michigan); 2) Mackintosh, 'The Rocks', 1927 (in Howarth); 3) Mackintosh, 'Le Fort Maillert', 1927 (in Howarth); and 4) Ike no Taiga, 'Mountain Landscape and a Waterfall', between 1750-1776 (Univ. of Michigan).

Regard the striking similarities, particularly between the first two images. Sesshu (1420-1506), the most renown of Japan's suiboku artists (acclaimed as the greatest painter alive during his stay in China by his contemporary Chinese painters), was prominently featured in books on Japanese art by the early 20th century in Europe and America, thanks to men like Ernest Fenollosa.

The idea that 'rocks' were a worthy subject of painting on their own, that they might be allowed to fill a canvas with little else, and that they were objects of immeasurable aesthetic value, in fact of religious veneration, was of course new to Western painters, and must have been a significant aesthetic revelation. The techniques of painting rock formations was an ancient and well-developed technique in China, and carried on by Japan, whose artists leaned towards either extremely soft (e.g., Uragami Gyokudo and Hasegawa Tohaku) or more sharply formed outlines (e.g., the Kano school and Hokusai's painted landscapes) as found in Mackintosh. The numerous suiboku techniques of painting rock formations, each with a name, and the manner in which Mackintosh has attempted to assimilate them, requires a paper of its own and will not be delved into here in depth; suffice it to say that even to an untrained eye, various aspects of form, shadowing emphasis, over all composition and detail, and what one might call 'directionality' and 'presence', take from suiboku models.

Just to point out a few specific points of interest, observe in Mackintosh's 'The Rocks' how 1) the smaller foreground rocks on a flatter ground surface paralleling those Sesshu, and 2) the creation of open spaces toward which the rocks lean, 3) the various similarities in the grouping of rocks, and of course 4) the similar layering technique of the rock surfaces.

The second pair is a comparison of Mackintosh and Ike no Taiga (1723-76), one of the great 'bujin-ga' (literati painting) painters of the Edo period along with Yosa Buson. While Mackintosh's 'Le Fort Maillert' rock textures might resemble other suiboku works better, the fundamental compositional equivalence of squat, massive, squarish rocky formations, filling up much of the picture space, one taller with a waterfall between them, is worth noting. In Mackintosh's work, the waterfall has been transformed into a vein of the rock itself, but its fluvial origins can be discerned. The classic example of this type of squarish rock formation is Fan Kuan's (late 10th to early 11th century) iconic scroll painting 'Travelers among Mountains and Streams' (谿山行旅図) at the National Palace Museum in Taipei, and which is also characterized by broad, flat rock surfaces.

Some further observations regarding Mackintosh's spouse, Margaret Macdonald

Mackintosh's wife Margaret also incorporated various Japanesque qualities into her art, as discussed earlier, and can also be seen in her painting 'The Opera of the Seas' (between 1903-15, whereabouts unverified) shown above. This may be fruitfully compared to the design of Edo period lacquer picnic boxes, such as the one at the Suntory Museum of Art (Tokyo) to the right, for instance. Note the parallels in bold contrapositions of rectangular sections and curving lines; and motifs such the use of bands of scattered flowers and hanging screen-like forms. Regarding the picnic box: "The tiered picnic box was a set of picnic utensils with a handle used on outdoor excursions such as flower viewing parties. ... The design is rich in allusions to Japan's aristocratic court culture including images of court screens used by aristocratic women, the bugaku dance and paulownia combined with phoenix motifs." (Suntory Museum of Art, Iwai: Arts of Celebration, 2007) Both Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Margaret Macdonald looked to Japan as a rich store of inspirational ideas, and as has been emphasized elsewhere on this site, from the early 20th century onward Western artists utilized an increasingly diverse array of Japanese arts and crafts in their work.