Architectural Japonisme Continued

建築のジャポニスム II

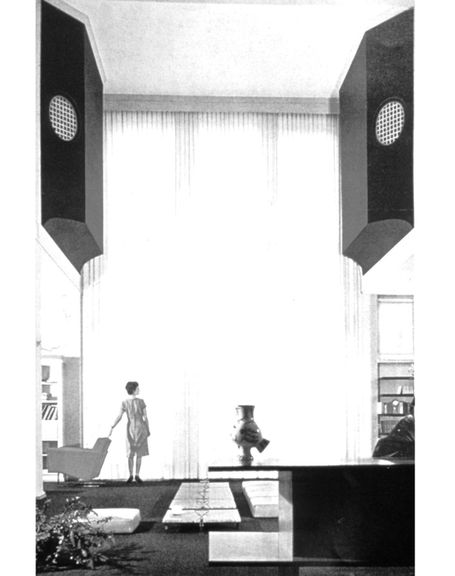

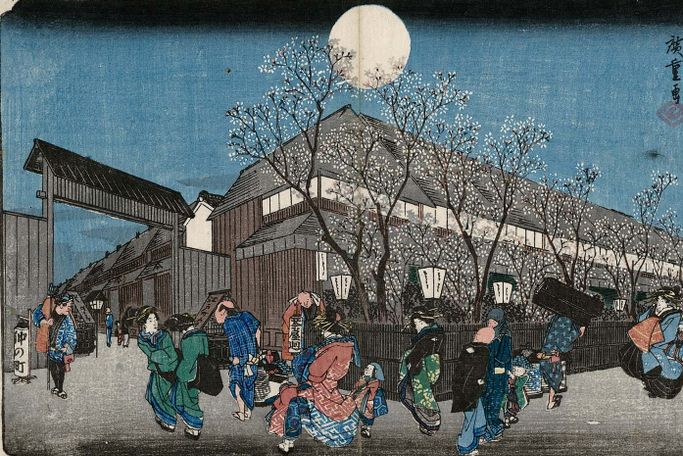

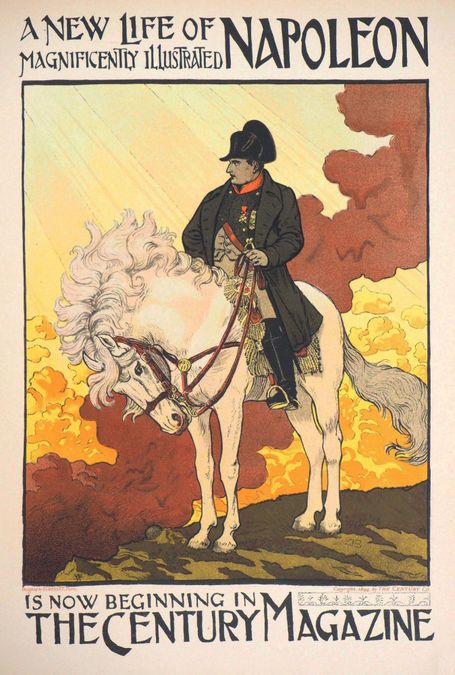

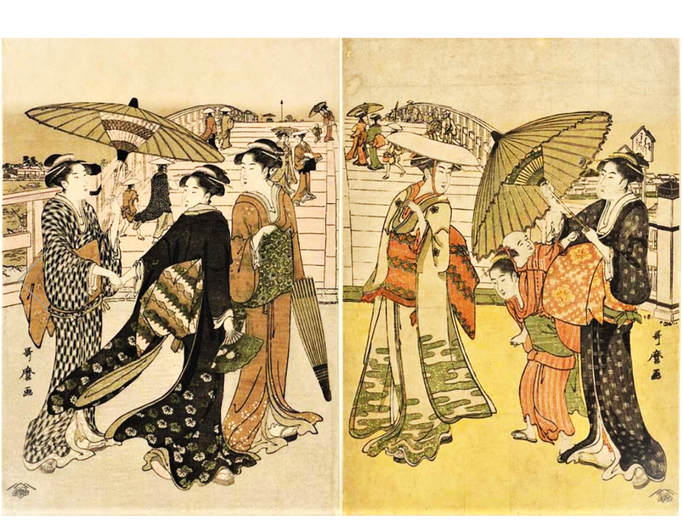

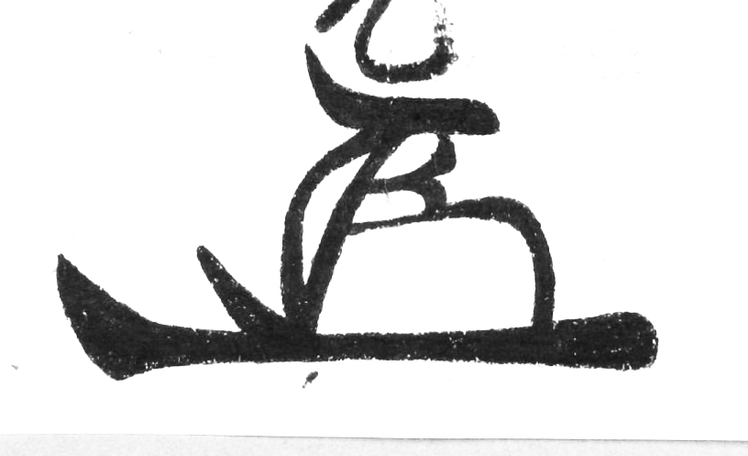

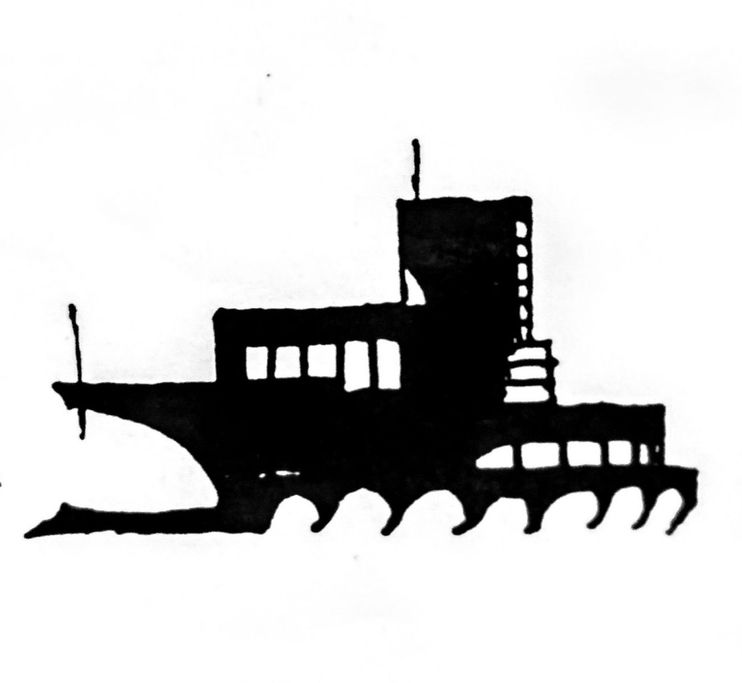

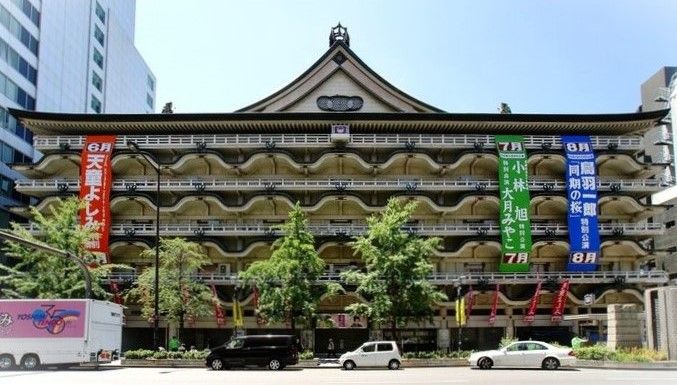

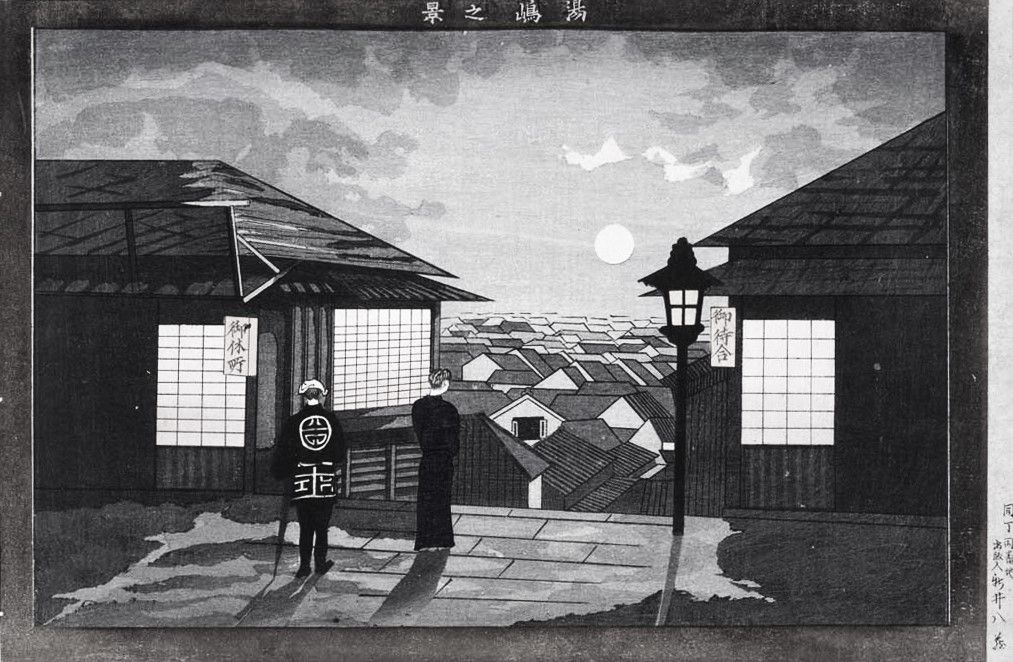

Illustration: Inoue Yasuji (1864 - 1889) Tokyo Theater, Chitoseza Scene, 1884

Table of Contents

1. Japan as a Symbol of the Ultra Modern in Design, 1890-1915

2. Le Corbusier Japonisme and the Apotheosis of C-E Jeanneret

3. Eric Mendelsohn: Japonisme in Architectural Expressionism

4. Philip Johnson: From Modernist Subtraction to Post-Modern Addition

5. Murano Togo: Rethinking Post-Modernism's Origins

Uploaded 2023/6/29 Under construction

Japan as a Symbol of the Ultra-Modern in Design, 1890-1915

Yasutaka Aoyama

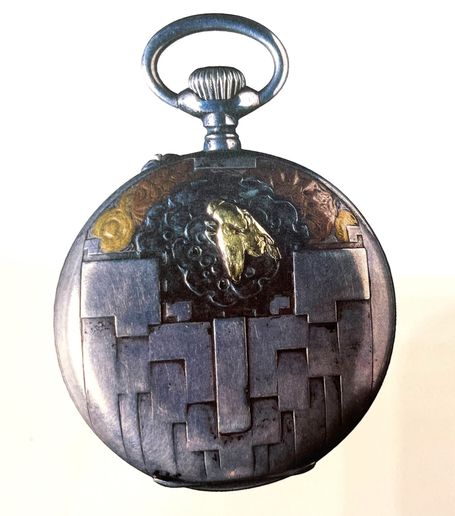

Japan near the turn of the century was a nation metamorphizing into something quite different from what it was three decades earlier. Despite the average man's housing, dress, and lifestyle having changed only superficially, the elite of society, including intellectuals and artists, had undergone a revolution that brought Japan to the forefront of global innovation and modernity. Particularly impressive was the fact that, probably more so than the Japan of today, late Meiji Japan was a nation that continued to excel as before in traditional arts in unbroken continuity and quality, as well as being on par with the West in terms of the avant-garde. Original woodblock prints continued to be produced actively, and kogei craftsmanship, whether in metal, porcelain, ivory, or wood, reached astonishing levels that have been commonly characterized as 'chozetsu giko' (超絶技巧) which might be translated as 'virtuoso craftsmanship' (literally, something like 'transcendent craft virtuosity') that have never been surpassed, if even rivaled.

Western ideas of Japan too were changing. The painter Alfred Stevens, in his Impressions sur la peinture (1886) perceived in a Japan a strong "element of modernity" and that the Japanese were in fact, no less than Europeans, true Impressionists. Those changes in attitude could be seen not only in books introducing Japan and its art, but even in science-fiction literature:

"Thence they wandered at last to the walls of the hall. It was decorated in long painted panels of a quasi-Japanese type, many of them very beautiful. These panels were grouped in a great and elaborate framing of dark metal, which passed into the metallic caryatidae of the galleries, and the great structural lines of the interior. The facile grace of these panels enhanced the mighty white effort that laboured in the centre of the scheme."

H. G. Wells, When the Sleeper Wakes (1899), Chapter VI The Hall of the Atlas

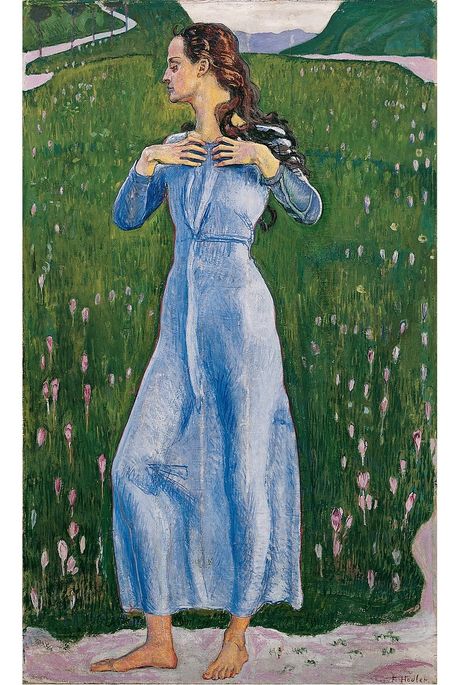

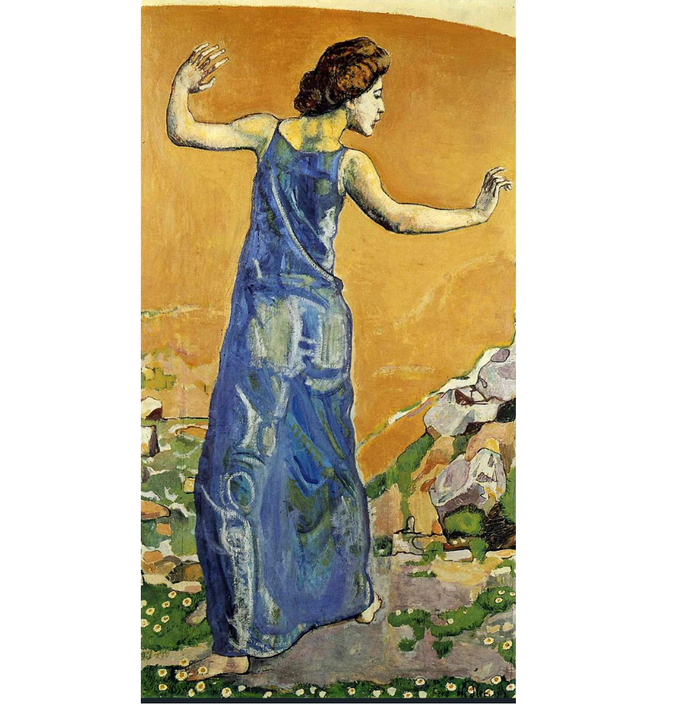

So wrote Wells in one of his most ambitious and highly acclaimed science fiction novels, When the Sleeper Wakes (The Sleeper Awakes), set in the 22nd century, over 200 years in the future from his time. He was describing the chamber of the "Council" that ruled the world, the most powerful, wealthiest, and modern seat of power to be possibly imagined, and it was in an important aspect aesthetically, "quasi-Japanese". The councilors wear long robes, but why in a society of the distant future they should wear robes is not explained. Somehow wearing robes (somewhat reminiscent of kimono as in the original illustration below, left) in a hall of Japanese decor, is seen as a fitting setting for the future.

The popular image of Japan had changed over the years from one of a feudalistic, isolated society to a fashionable place to go, such that by the 1890's, in forgotten novels as George Gissing's The Odd Women (1893), one of the main characters, Everard Barfoot, who was until then looked upon quite disaprovingly by his astute cousin, after 2 or 3 years in Japan returns in marvelous condition and transformed----cultivated, suave, relaxed, and alluring:

"Excellent health manifested itself in the warm purity of his skin, in his cheerful aspect, and the lightness of his bearing. ... On sitting down, he at once abandoned himself to a posture of the completest ease, which his admirable proportions made graceful. From his appearance one would have expected him to speak in rather loud and decided tones; but he had a soft voice, and used it with all the discretion of good-breeding, so that at times it seemed to caress the ear. ..." (Gissing, 1893, Chapter 8 'Cousin Everard')

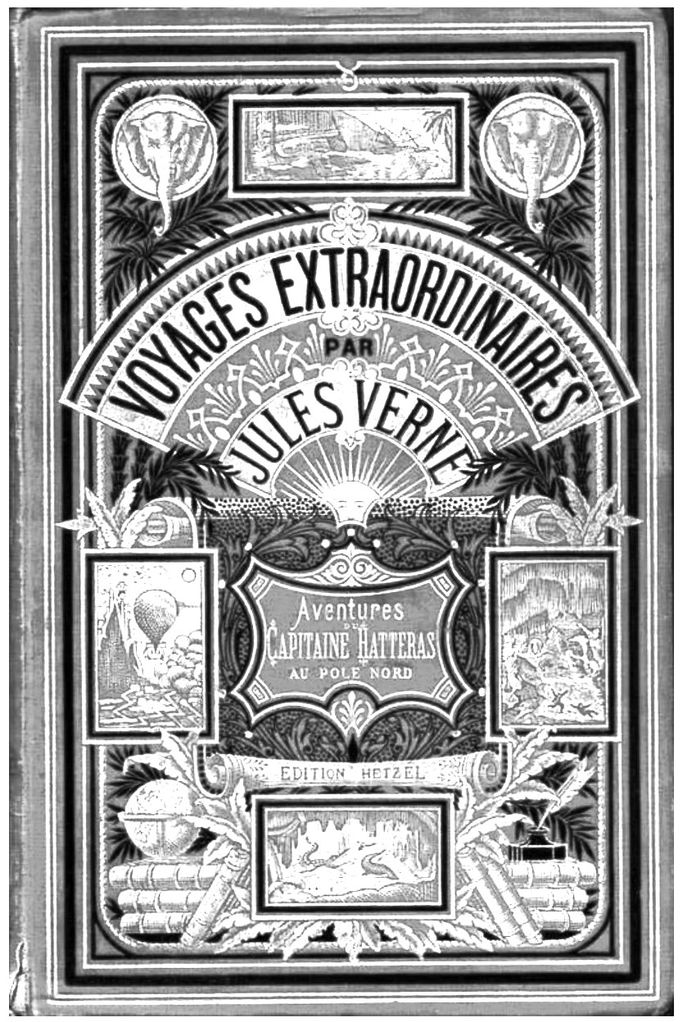

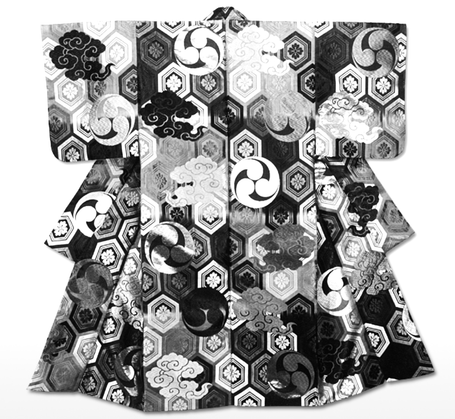

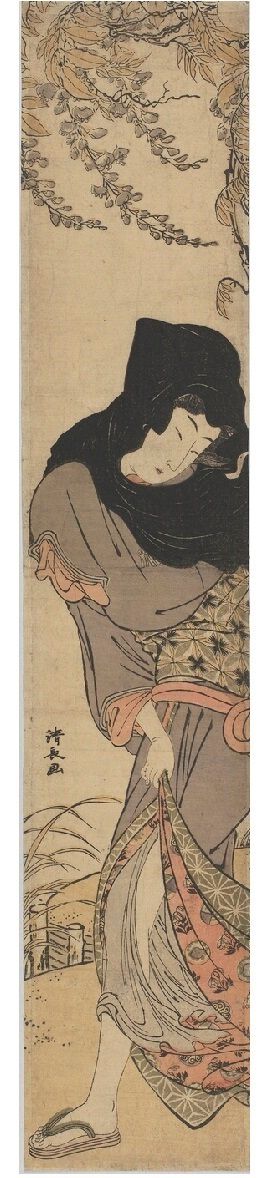

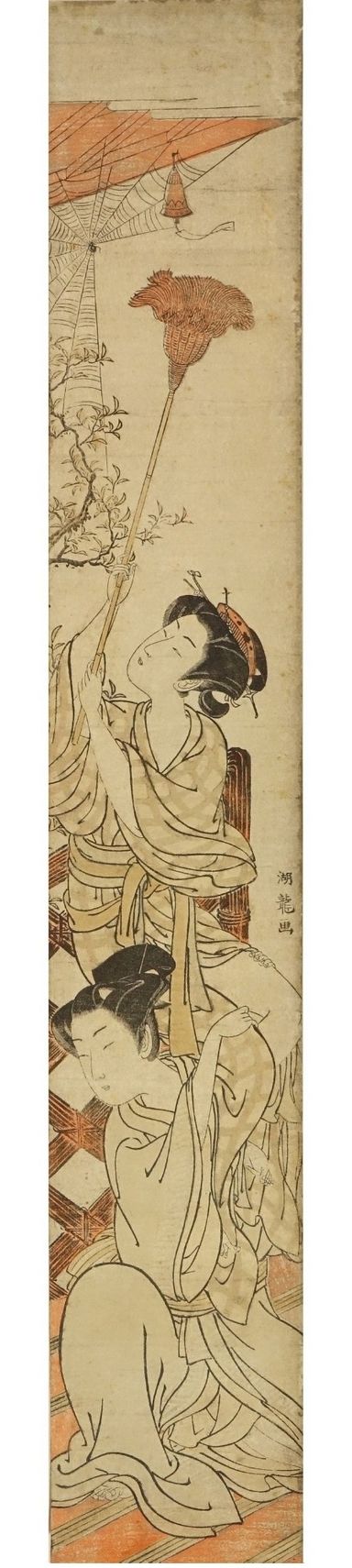

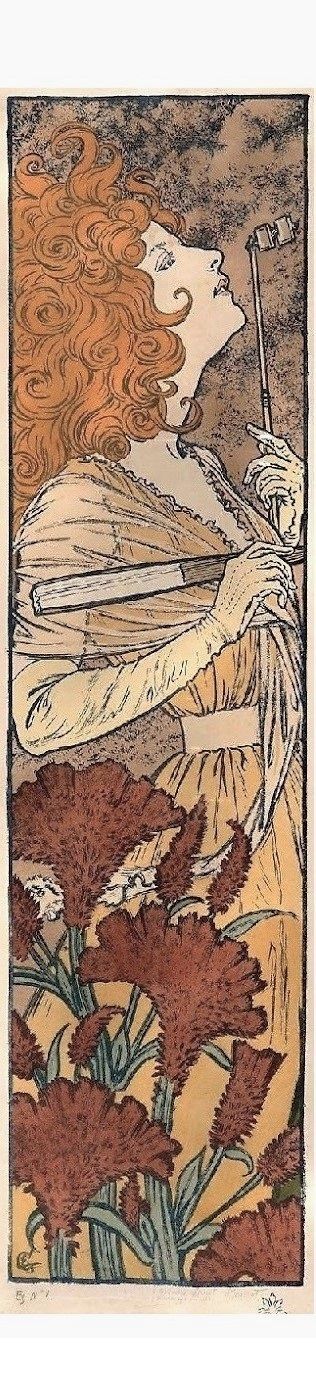

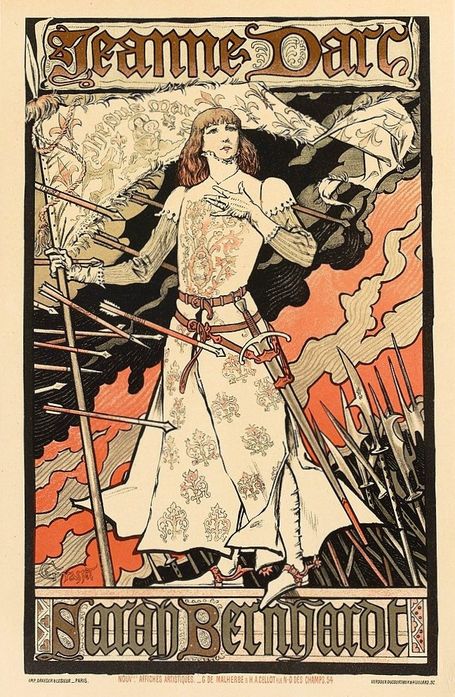

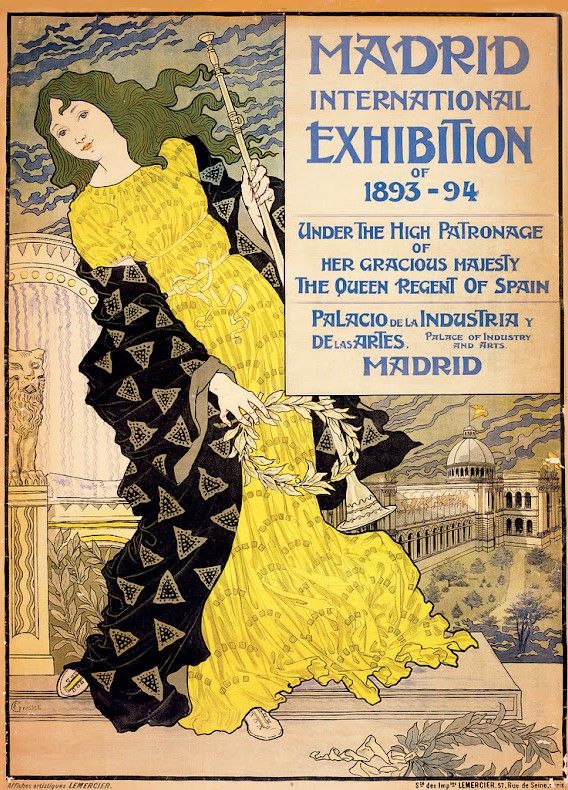

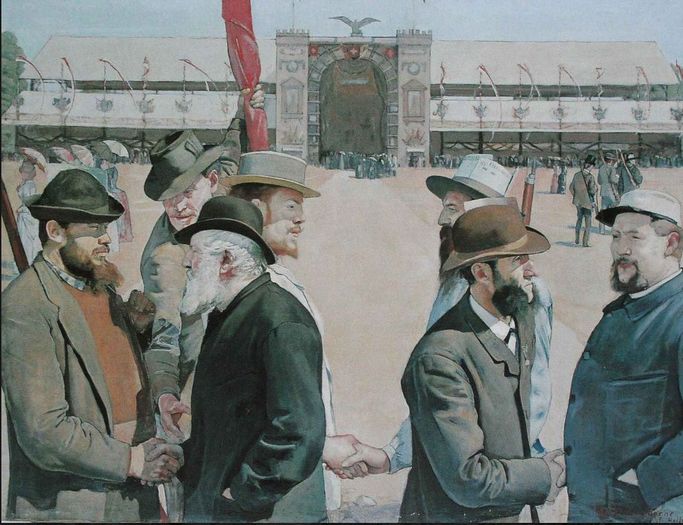

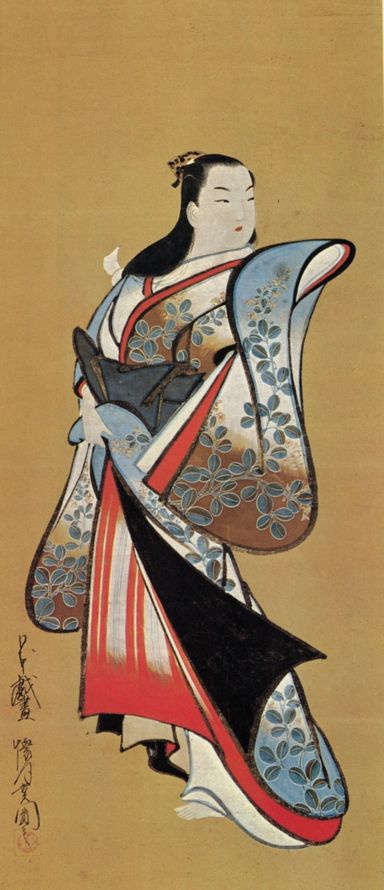

Whether or not it was all due to his experiences in Japan, certainly a stay there carried different connotations compared to coming back from India or Africa, or other parts of the non-Western world, as portrayed in contemporary novels. And japonisme too, had come to mean not a quaint archaism, a taste for a feudal culture preserved in time, but rather to symbolize cutting edge sophistication---the wave of the future. Thus aspects of Japanese art, whether kimonos, decorative panels, or Japanese style fans (as shown below, right) used to decorate the cover of Jules Verne's Voyages Extraordinaires, which included his tales of deep sea and outer space travel, were not simply expressing a taste for exoticism, they were associated in minds of artists and the general public with modernity in design.

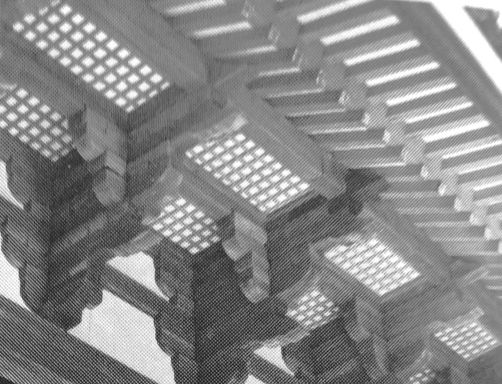

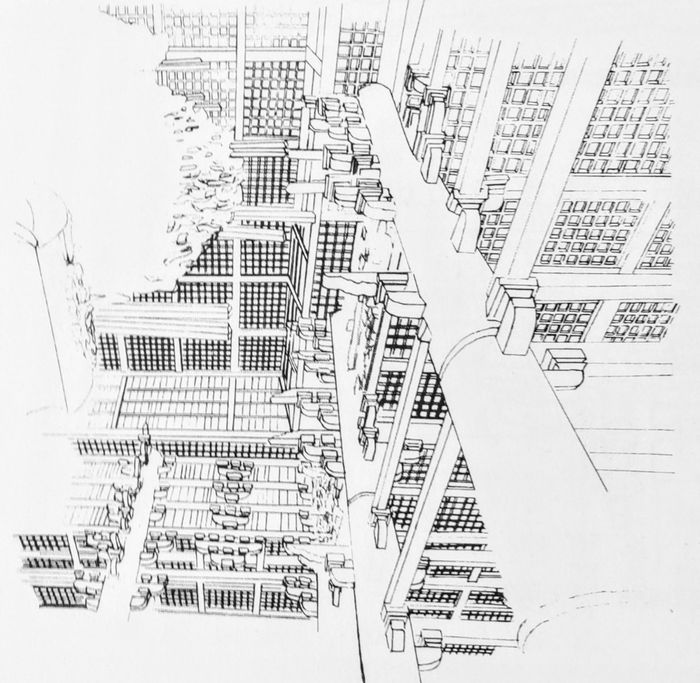

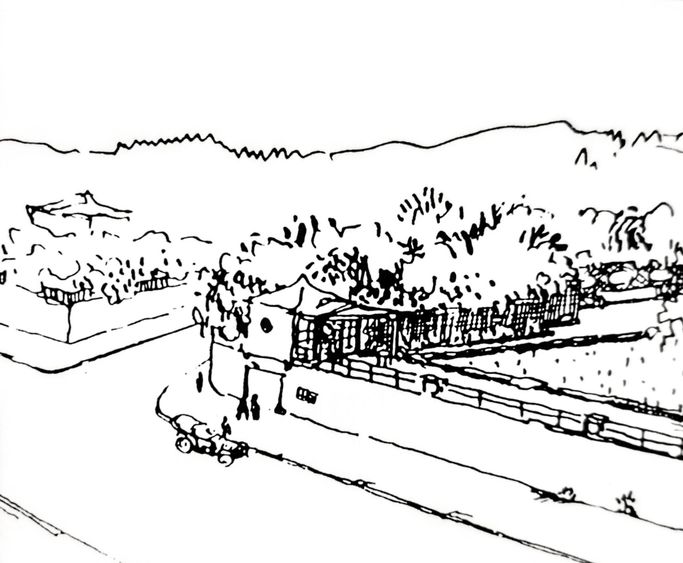

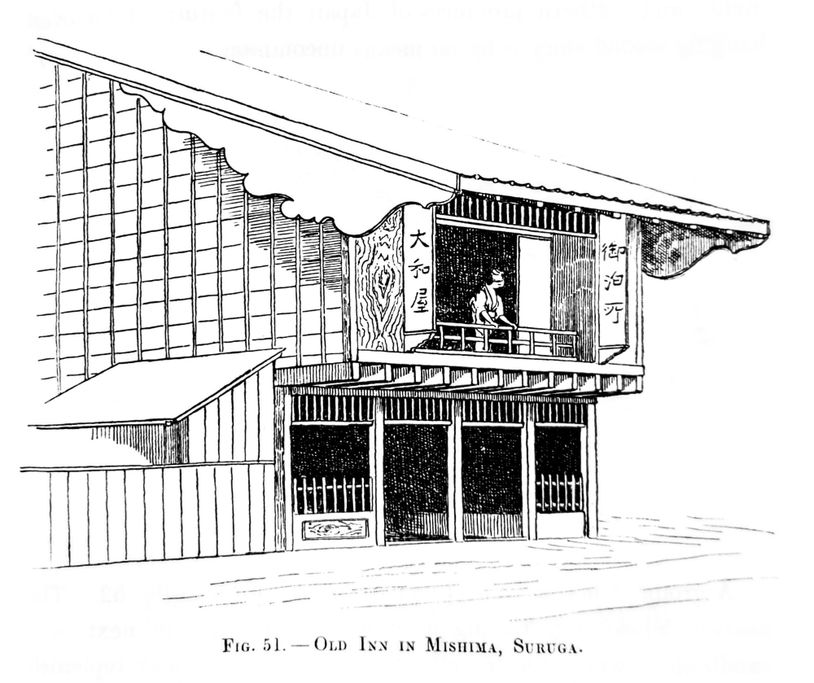

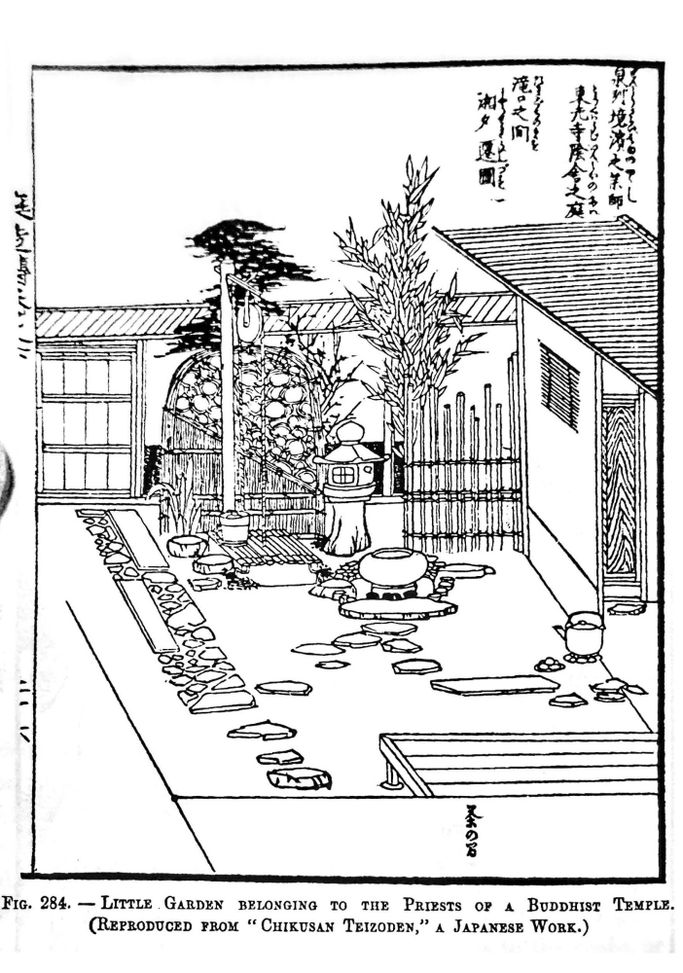

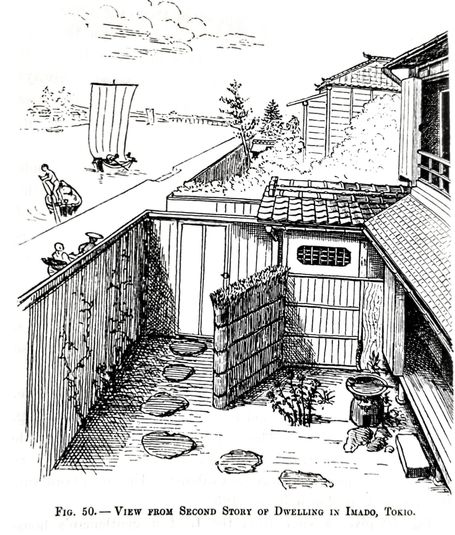

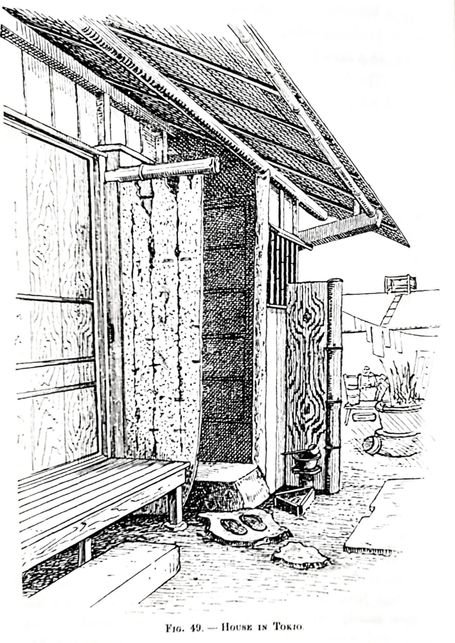

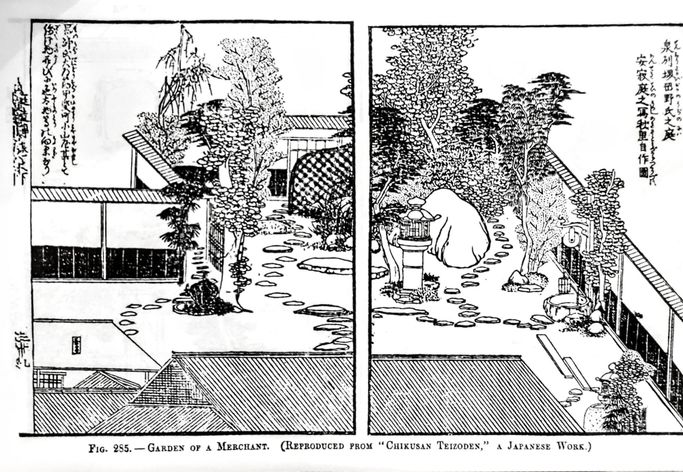

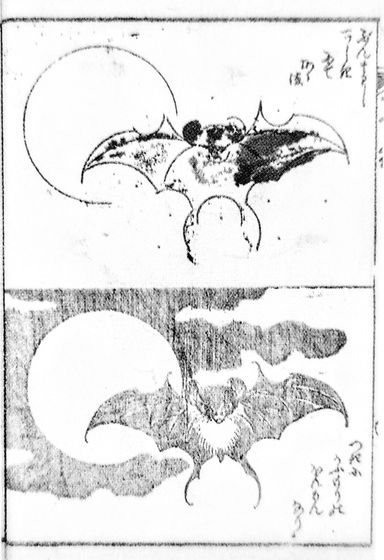

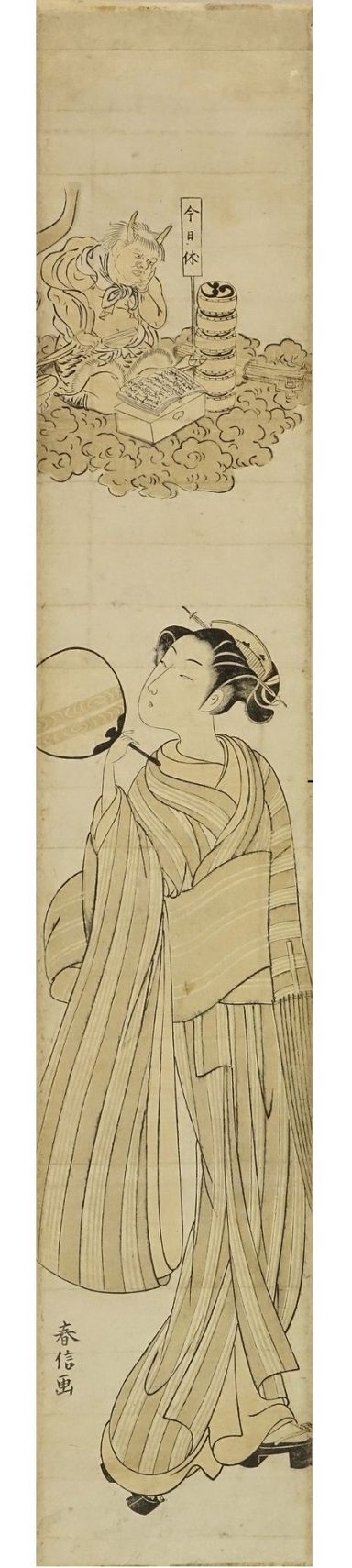

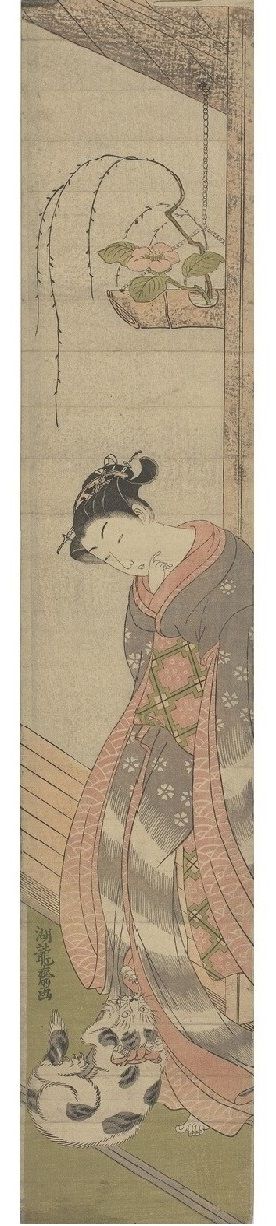

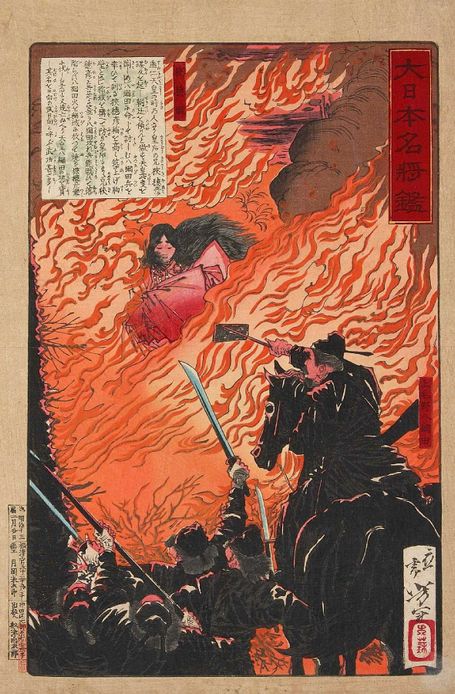

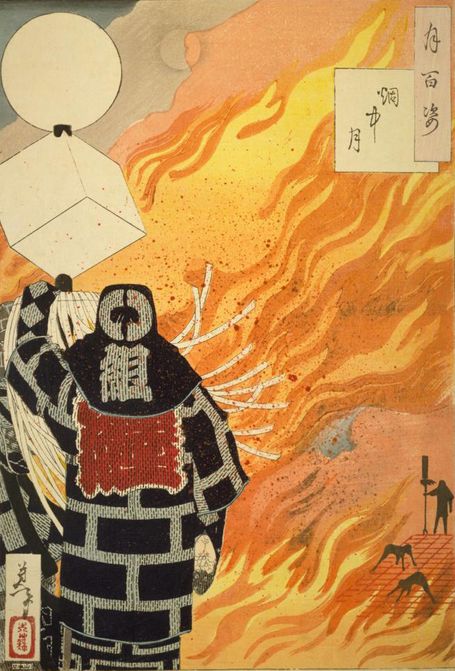

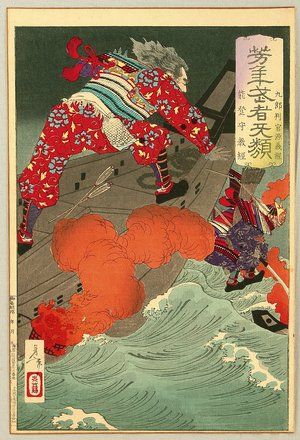

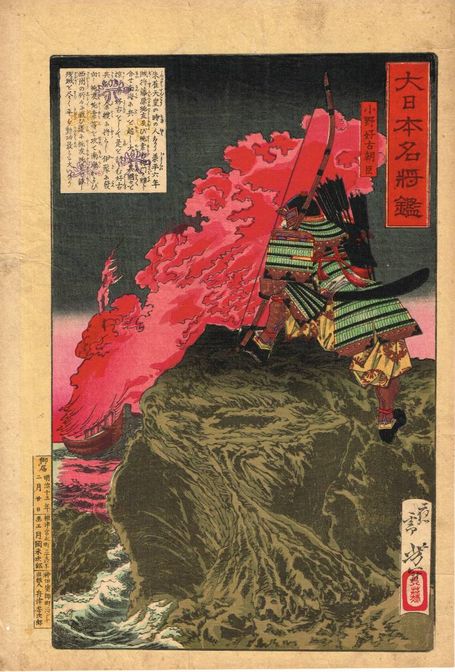

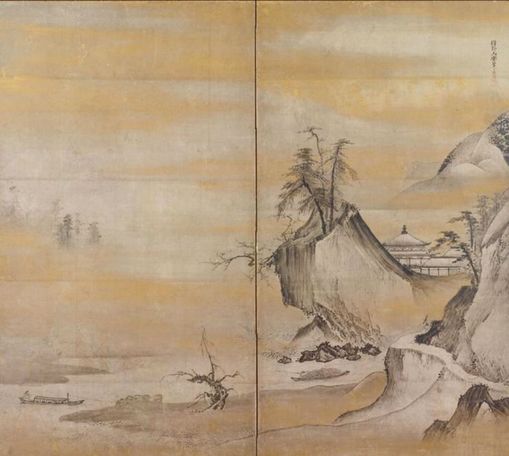

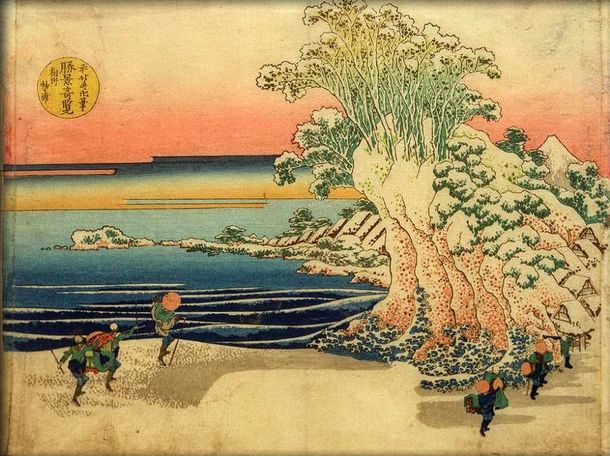

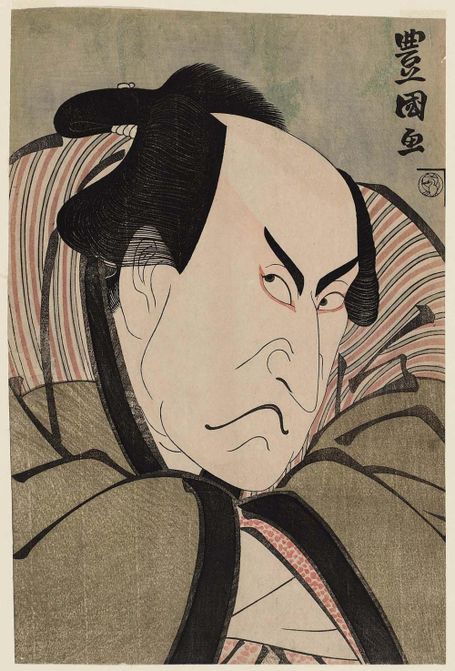

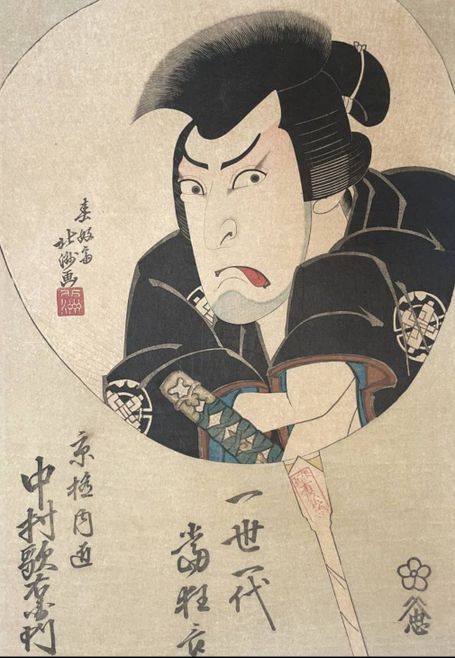

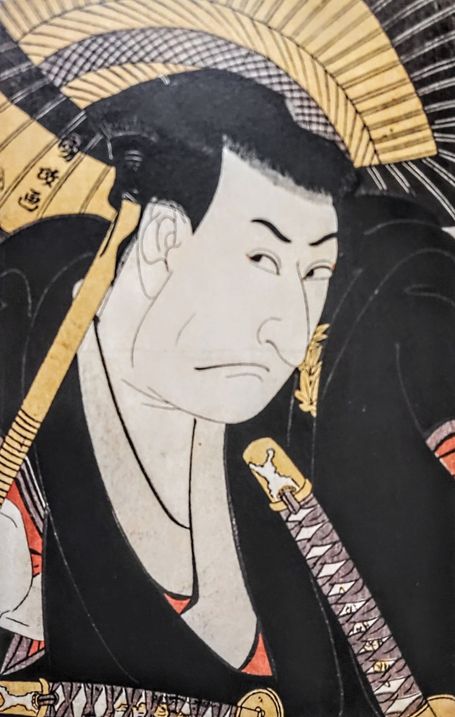

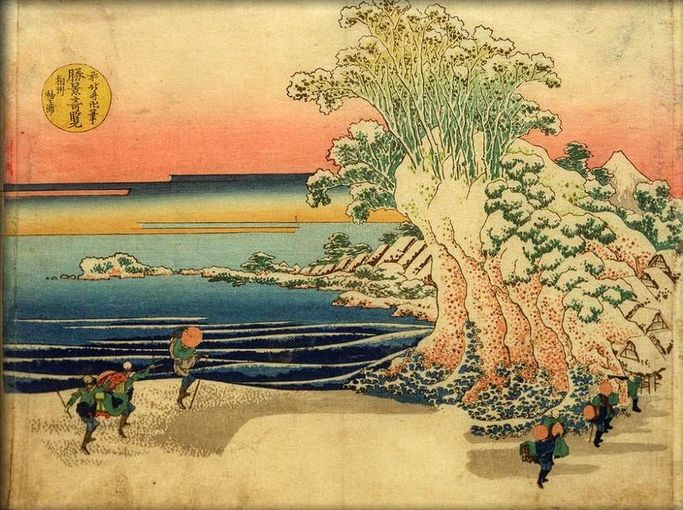

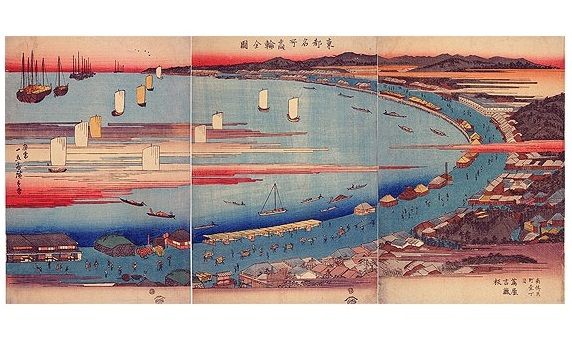

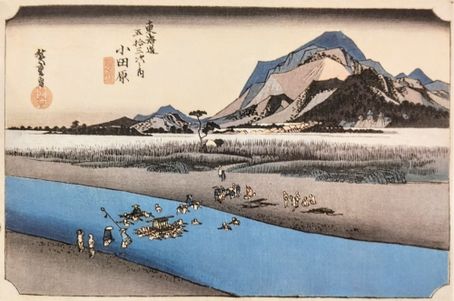

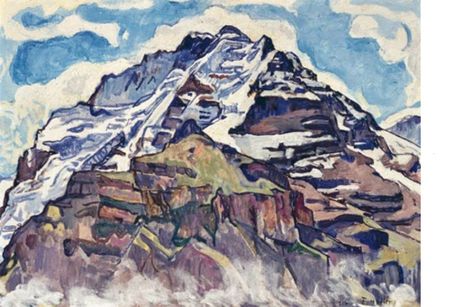

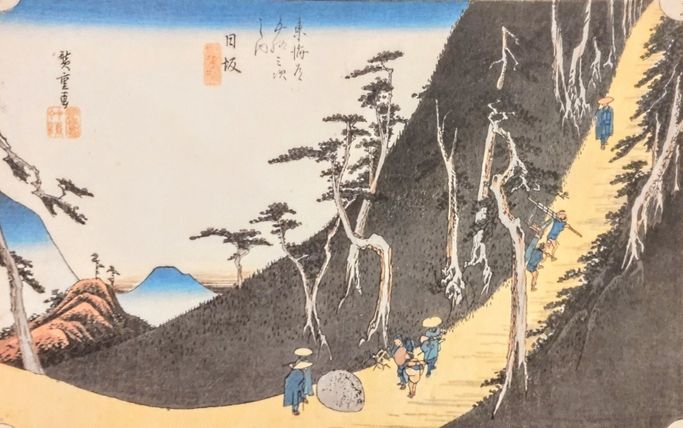

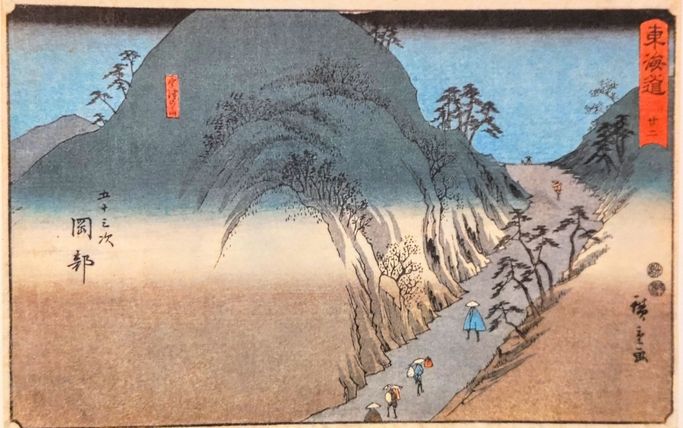

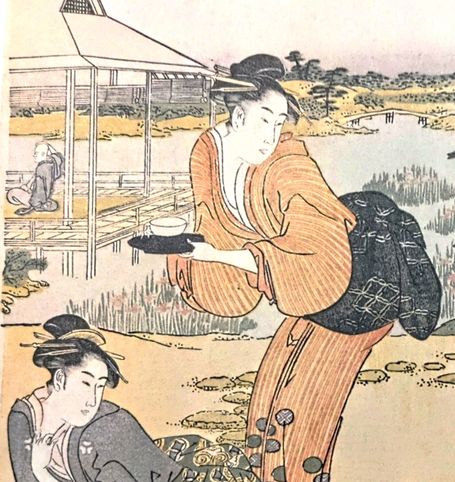

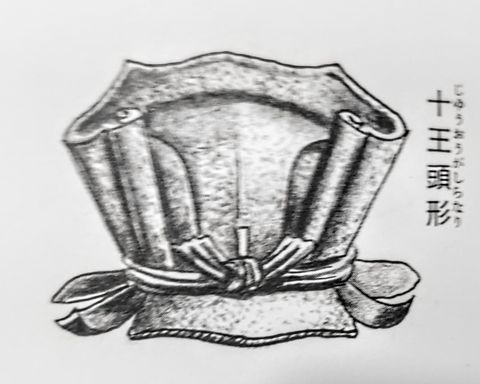

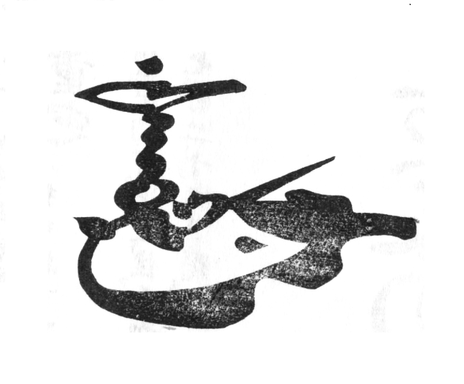

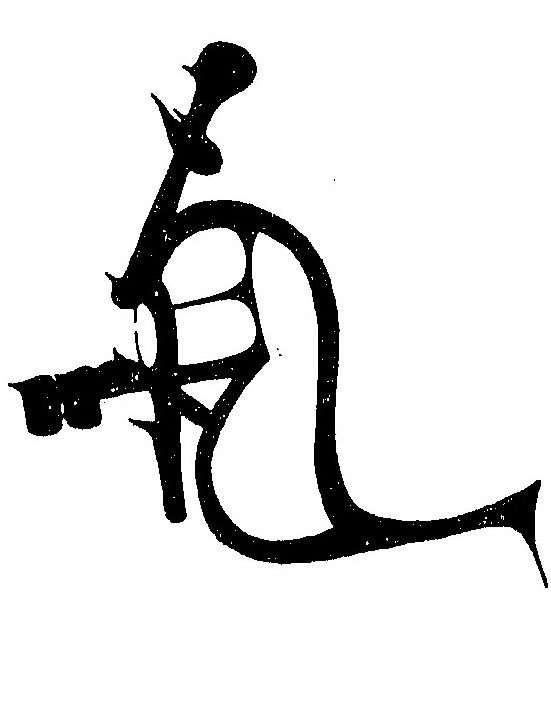

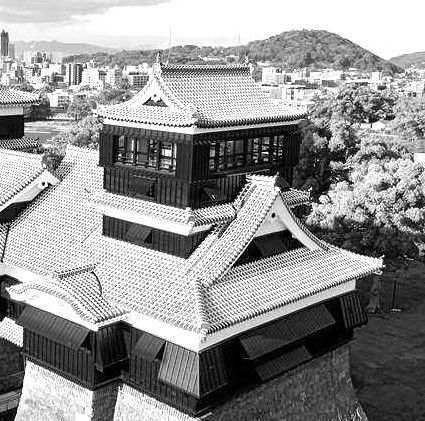

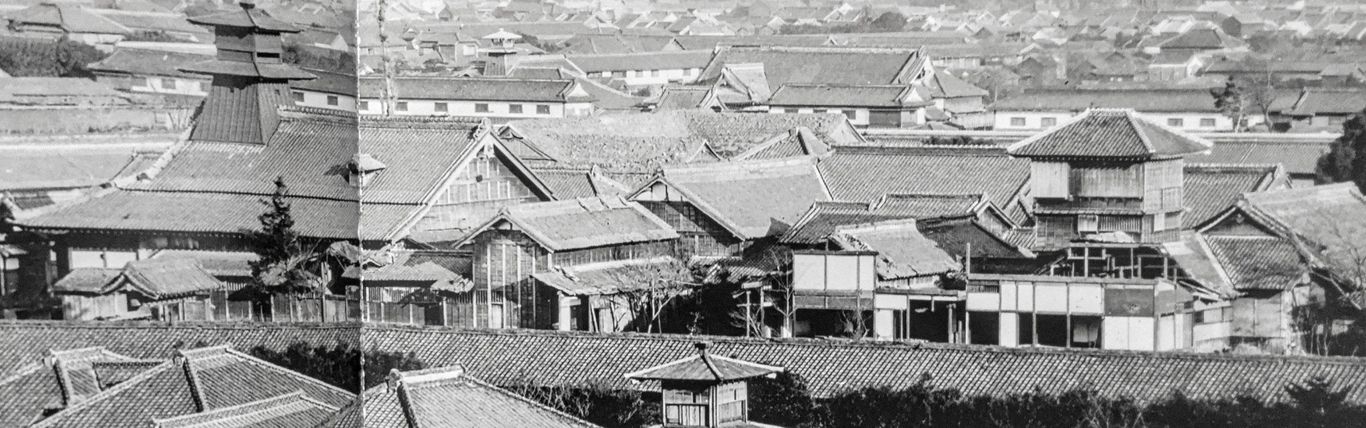

Regarding architecture, the ukiyo-e master Ando Hiroshige (1797 - 1858) is known for his daring angles and attention to unusual aspects of building and urban spaces. Later, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839 - 1892) in his series 'Tokyo Ryori Sukoburubeppin' (Gourmet Delights of Tokyo, 1871) featuring exteriors and interiors of dozens of culinary retreats in Tokyo, provided stunningly modern images of structures dominated by clean lines and novel architectonic conceptions. His contemporaries such as Yoshu Chikanobu (1838 - 1912, along with his disciple Yosai Nobukazu 1872 - 1944), Inoue Yasuji (1864 - 1889), and Kobayashi Kiyochika (1849 - 1915), among many others, competed in this Japanese golden age of 'architecture as pictoral art' to create compellingly images of secular and religious structures in daily use. European and American photographers, painters, and writers were also busy recording a variety of architectural landscapes in Japan.

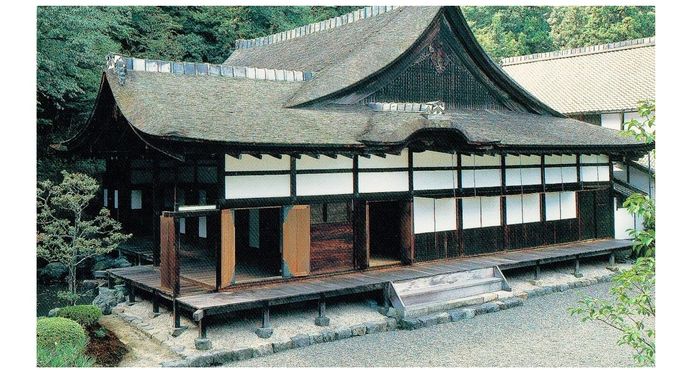

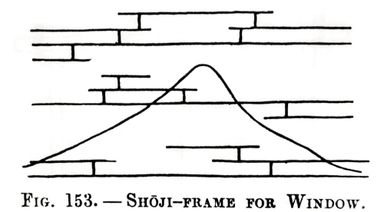

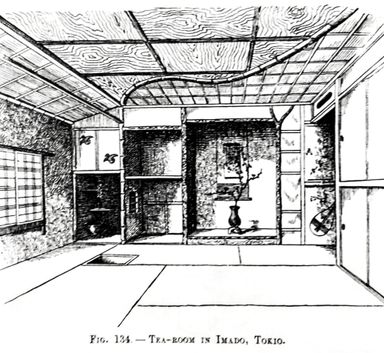

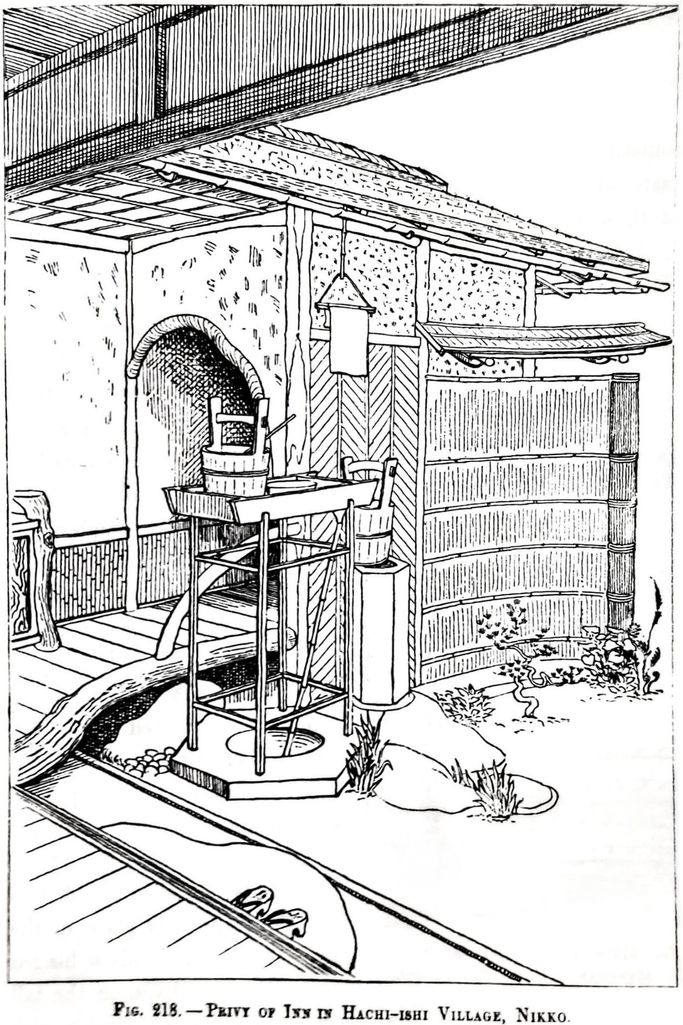

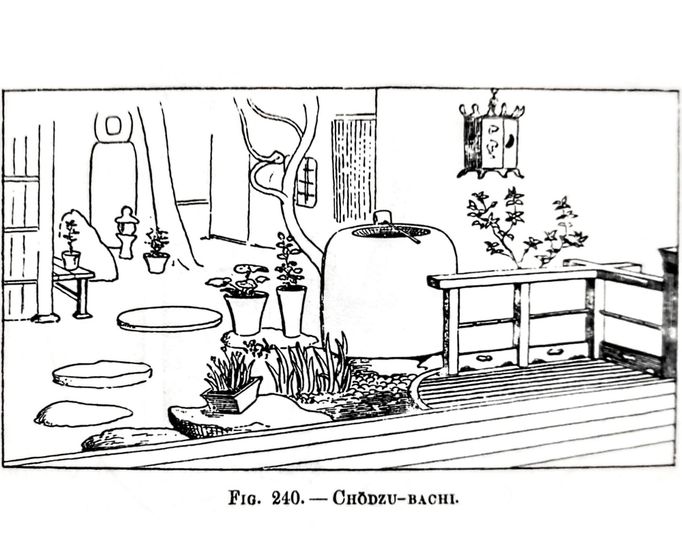

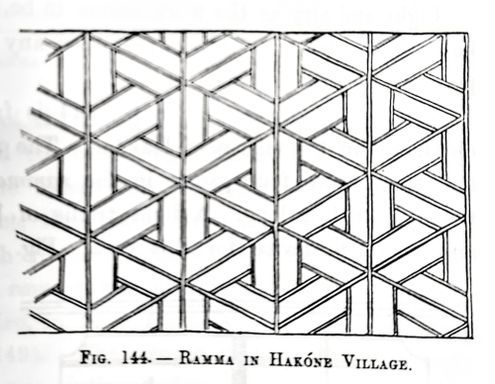

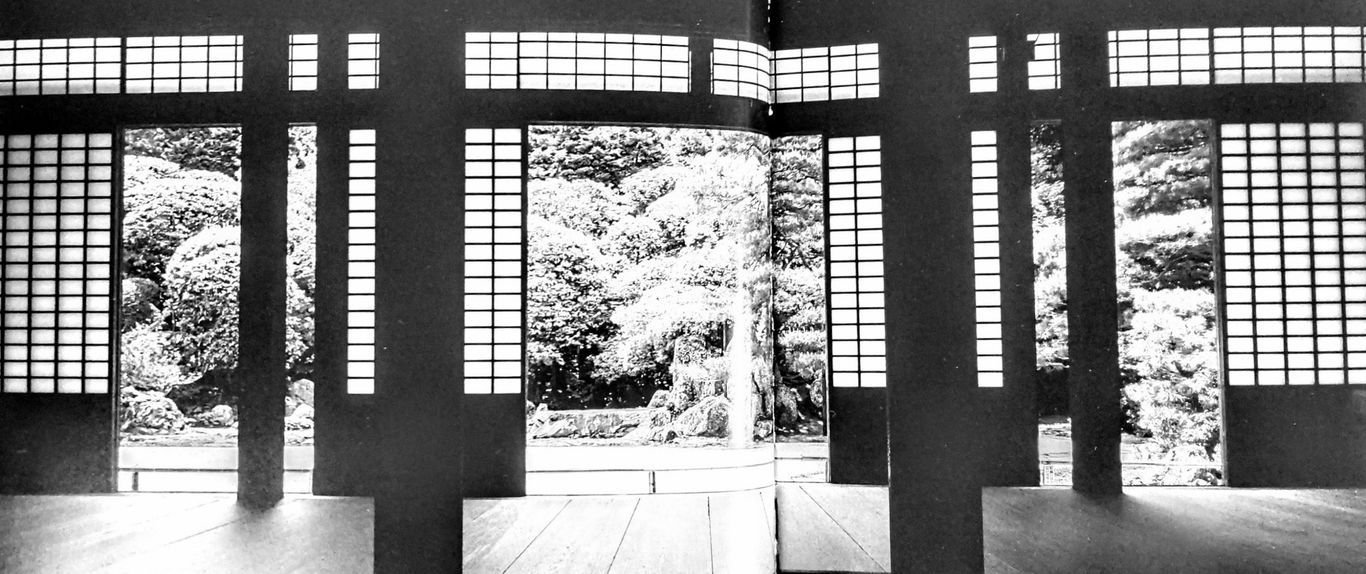

In 1886, Edward S. Morse, in his Japanese Homes and Their Surroundings, described in plain English, and with various illustrations, modern conceptions of architecture, such as open floor plans, a system of rooms based on the tatami module, built-in furnishings, multi-purpose rooms, and multi-functional furnishings, as well as asymmetrically intersecting wall planes and window placements. Others followed, including Ralph Adams Cram, Head of the Architectural Department of MIT and foremost authority of the Gothic style in America, who once graced the cover of Time Magazine (as he was considered one of America's greatest architectural authorities in his day). Author of the well-received Impressions of Japanese Architecture (1905), he recognized the future potential of Japanese interiors, writing:

"There is something about the great spacious apartments, airy and full of mellow light, that is curiously satisfying, and one feels the absence of furniture only with a sense of relief. Relieved of the rivalry of crowded furnishings, men and women take on a quite singular quality of dignity and importance. It is impossible after a time not to feel that the Japanese have adopted an idea of the function of a room and the method of best expressing this, far in advance of that which we have made our own.

From the moment on steps down from one's kuruma (rickshaw or carriage) and, slipping off one's shoes, passes into soft light and delicate color, among the simple forms and wide spaces of a Japanese house there is nothing to break the spell of perfect simplicity and perfect artistic feeling; the chaos of Western houses becomes an ugly dream."

Impressions of Japanese Architecture (1905), Chapter 5, Domestic Interiors

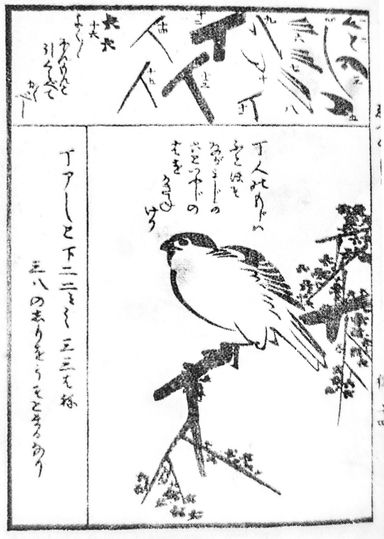

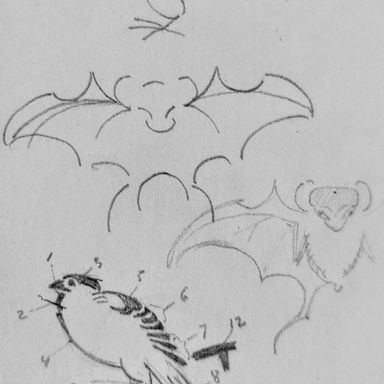

Is this not exactly the gospel of Modernism, an emphasis on functionality, spaciousness, simplicity, and light? Japanese art and architecture represented modernity in more senses than one, through a variety of mediums. Truly it was was the key to artistic Modernism itself, or so Frank Lloyd Wright wrote, regarding the significance of ukiyo-e prints:

"The gospel of elimination preached by the [Japanese] print came home to me in architecture as it came home to the French painters who developed Futurism and Cubism. Intrinsically, it lies at the bottom of all this so-called Modernism. Strangely unnoticed, uncredited."

Frank Lloyd Wright, The Japanese Print -- an Interpretation (1967), p. 91

The last line so aptly put, deserves to be repeated over and over again, until things are set right in our understanding of modern art and architecture:

"Intrinsically, it lies at the bottom of all this so-called Modernism. Strangely unnoticed, uncredited."

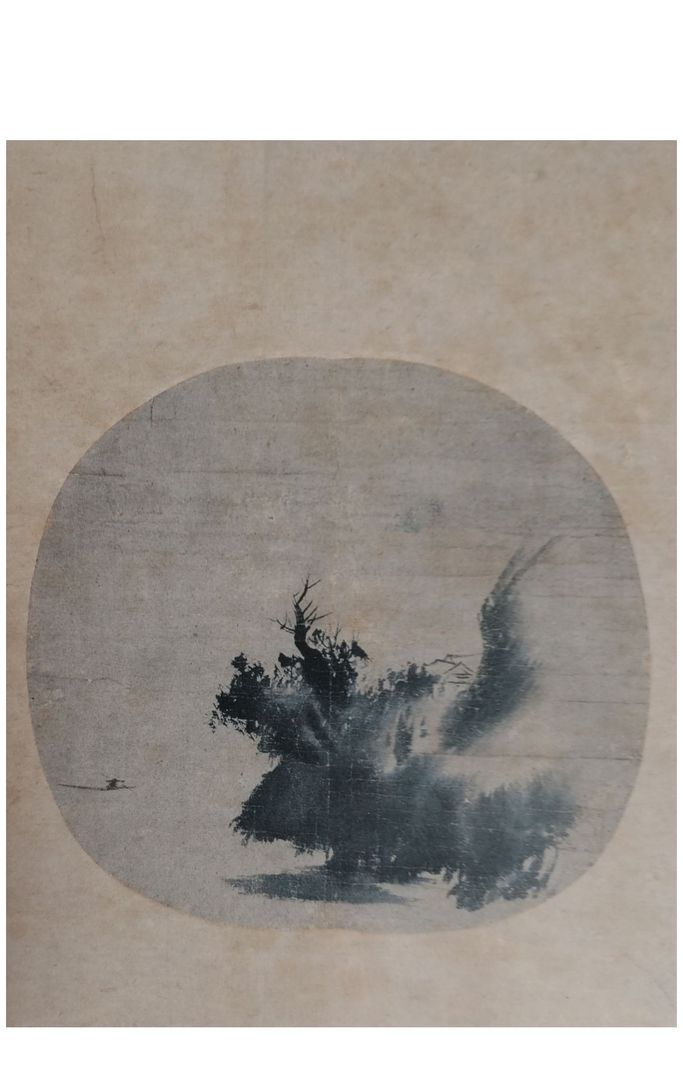

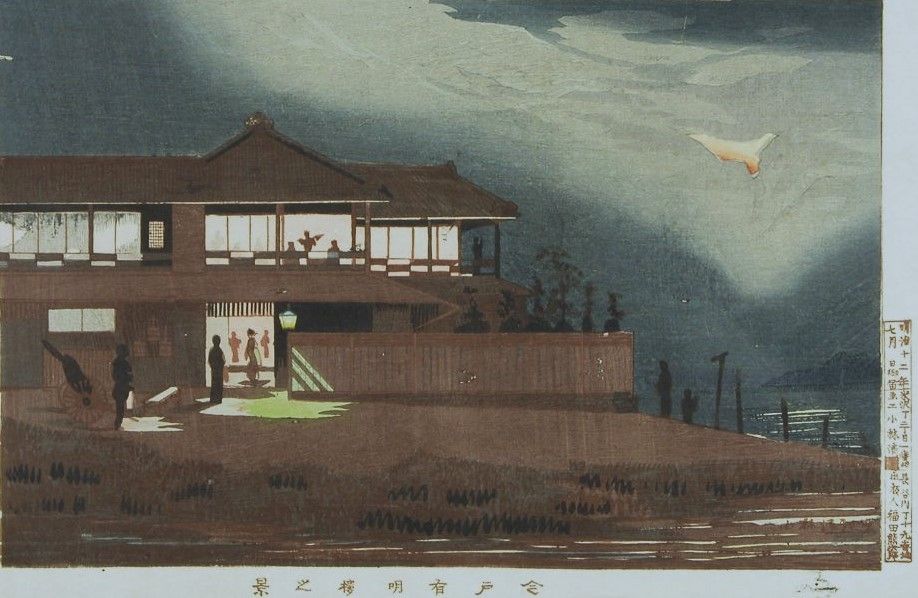

Above: Kyobayashi Kiyochika, 'View of Ariake Lake, Imado', from his series 'Tokyo Meisho-zu' (Famous Sights of Tokyo, 1879). Without knowing any better, seeing only the image without the Japanese writing, might it not be mistaken for a beautifully executed watercolor of a house designed by Greene and Greene or Frank Lloyd Wright?

Actual vs. Imagined Japan

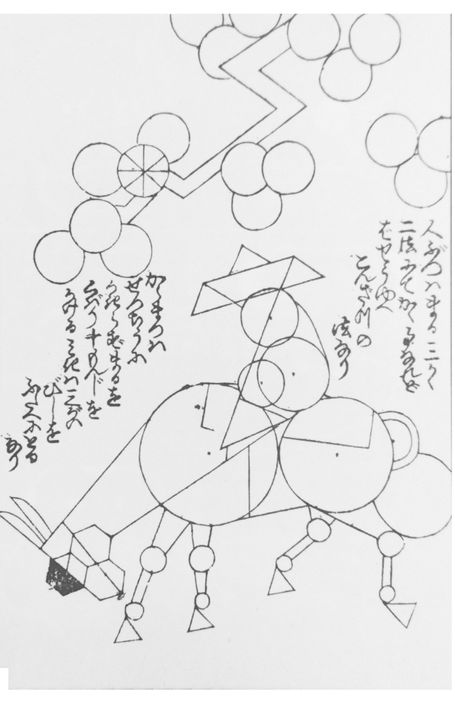

The true level of modernity and innovation (including that of architectural design), occurring in the real Japan of the early 20th century is hardly appreciated in the West, or for that matter, even in Japan today. Even before the Meiji Restoration, in the early 19th century, men like Tanaka Hisashige (1799 –1881) known as 'Karakuri Giemon' (Clever Contraptions Giemon) were building mechanical devices (some prescient of robotic conceptions) of the likes not yet achieved in the West at the time. The economic and technological advance of Japan is often seen as primarily a post-WWII phenomenon; in fact the postwar 'miracle' was but a continuation of a process going on for already three quarters of a century, if not longer.

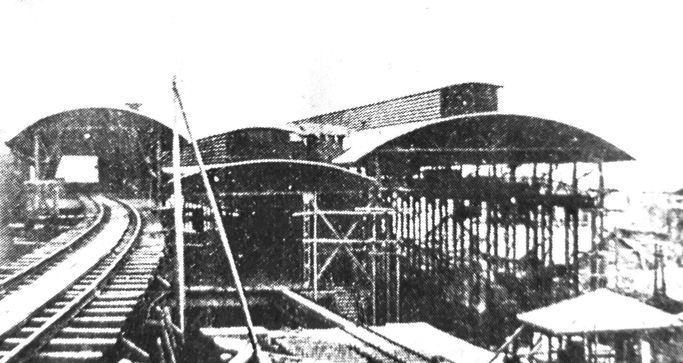

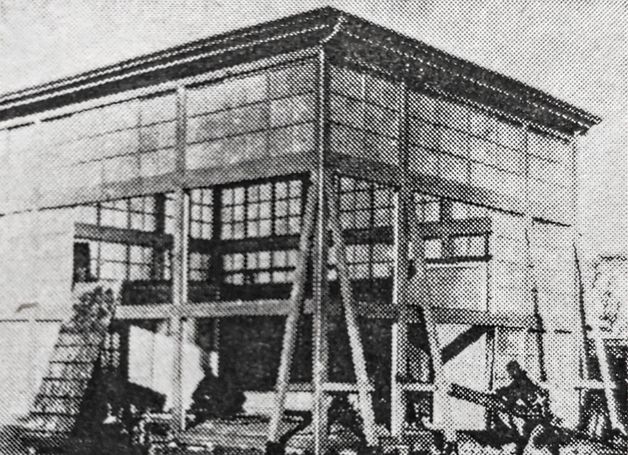

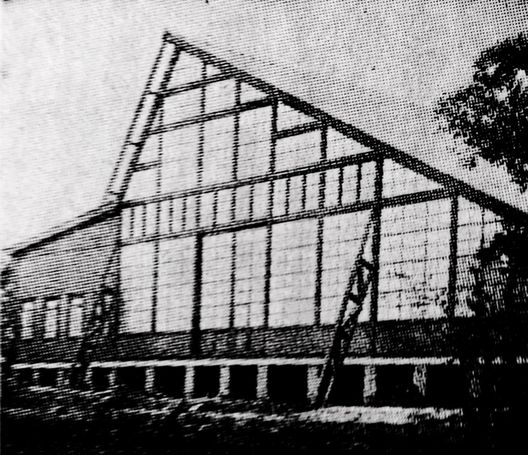

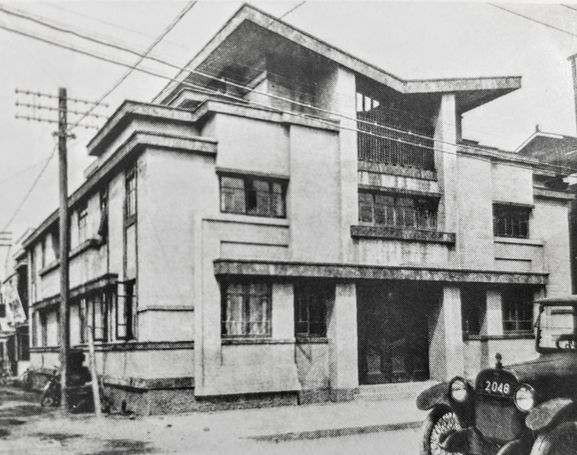

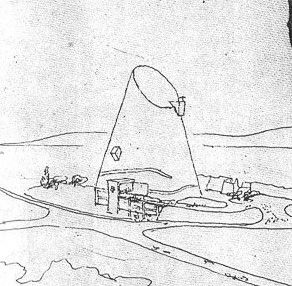

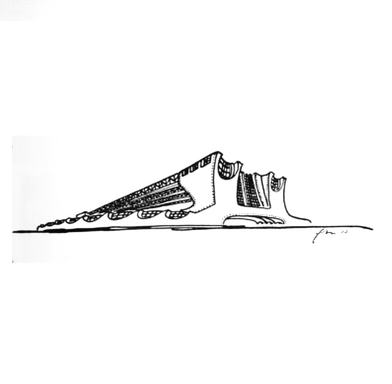

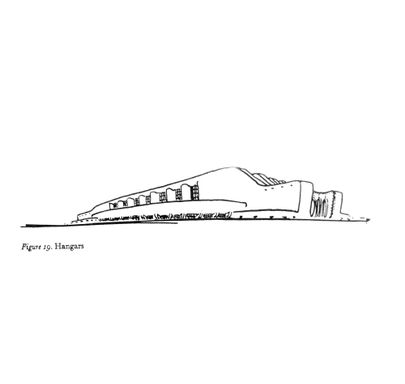

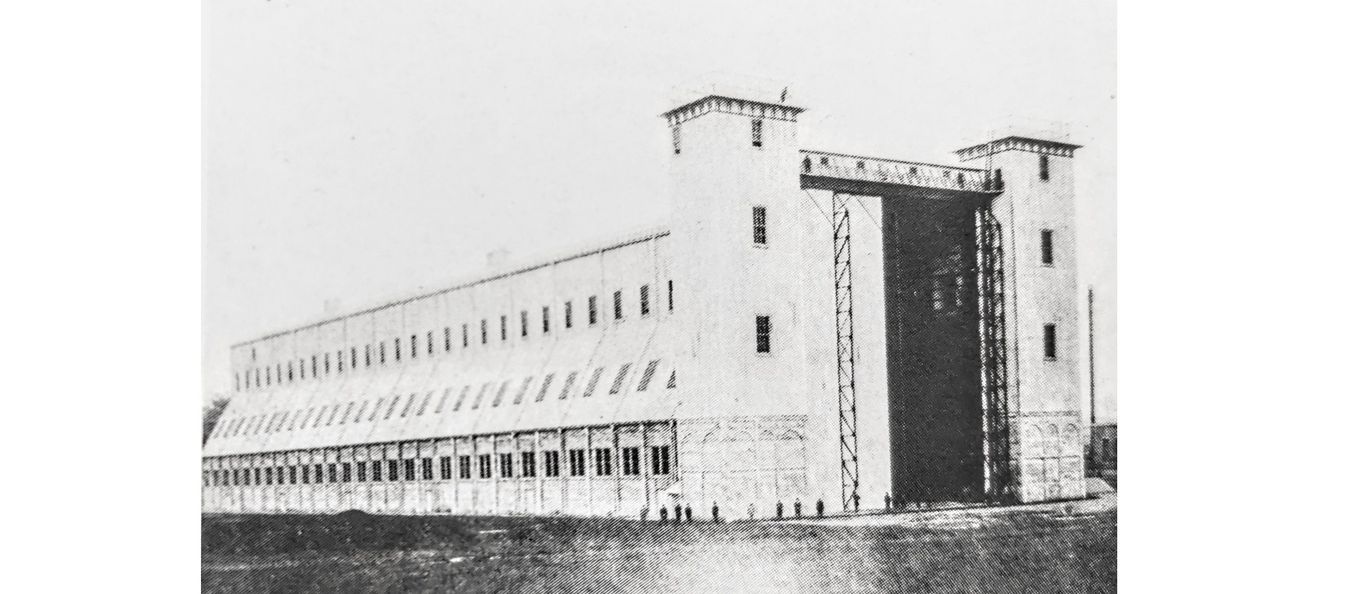

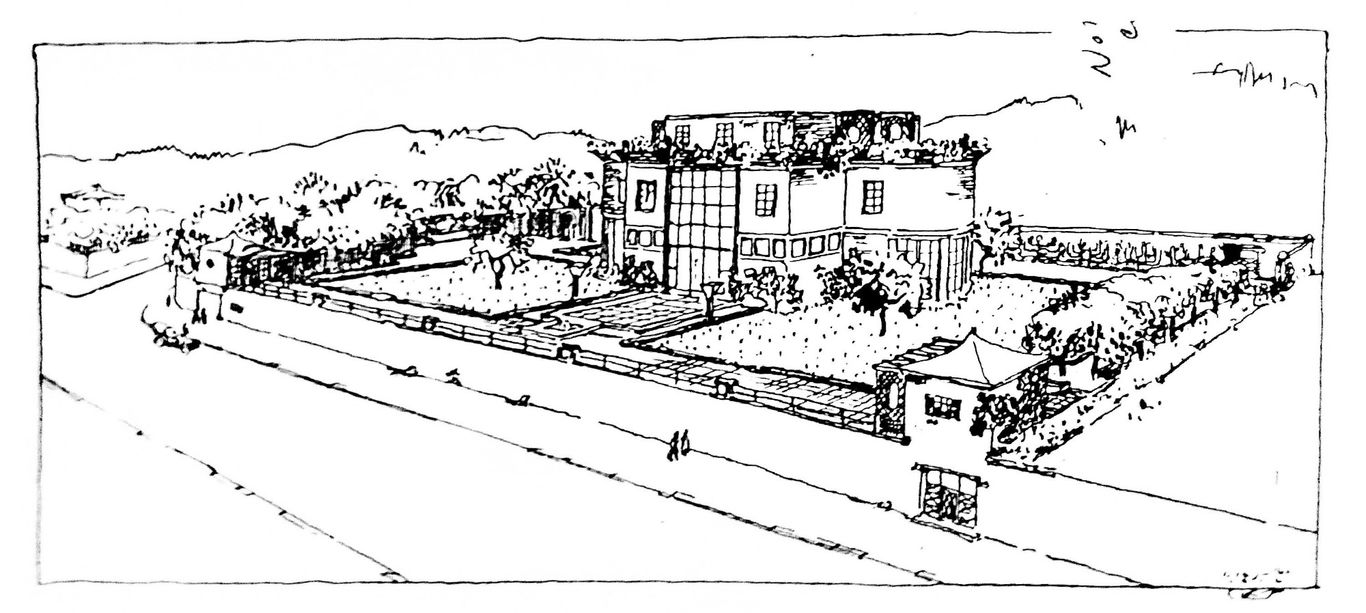

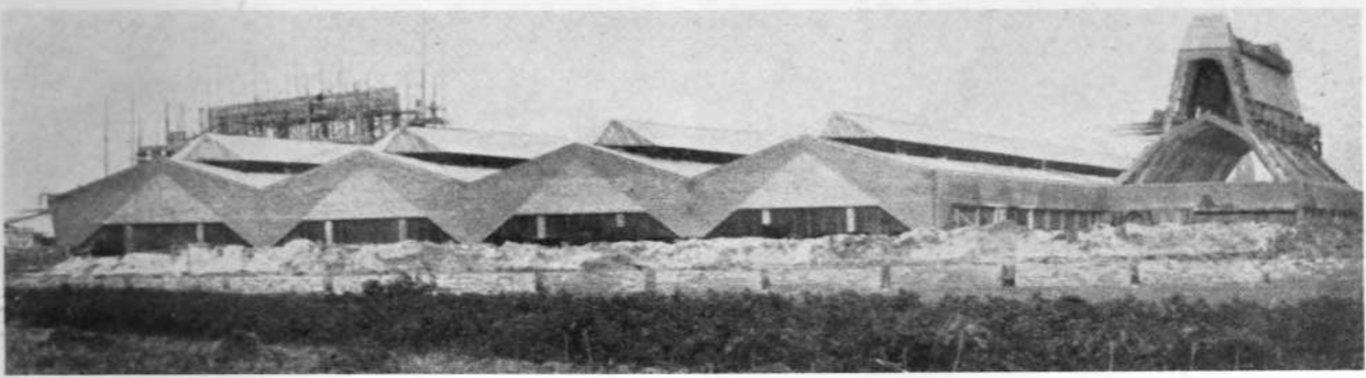

Uchida Yoshikazu (architect),Tokorozawa Hikosen Kakunoko (aircraft hangar), Tokorozawa, Saitama, 1913

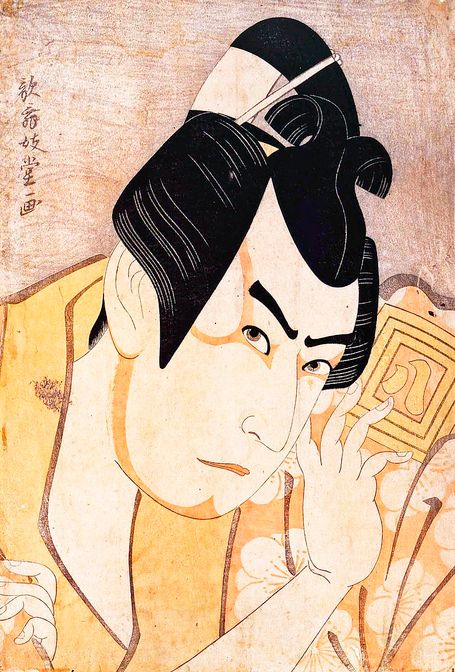

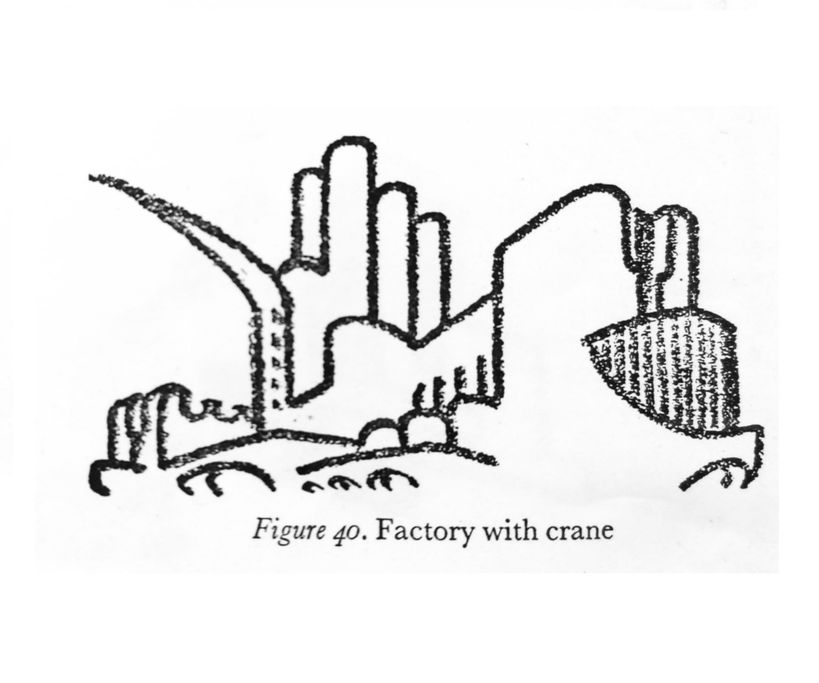

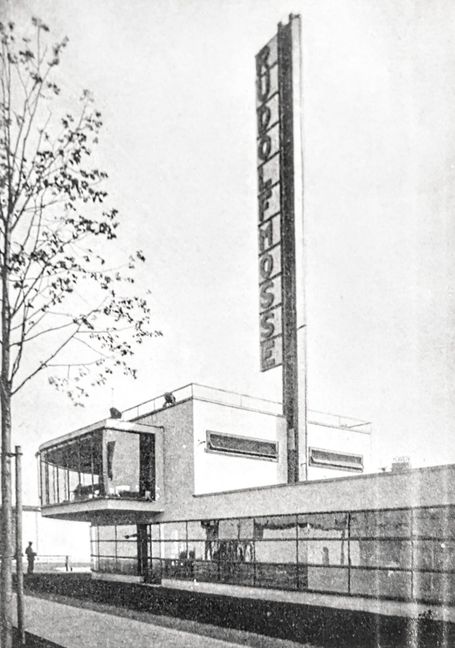

Japanese Cinema and Movie Studio Architecture

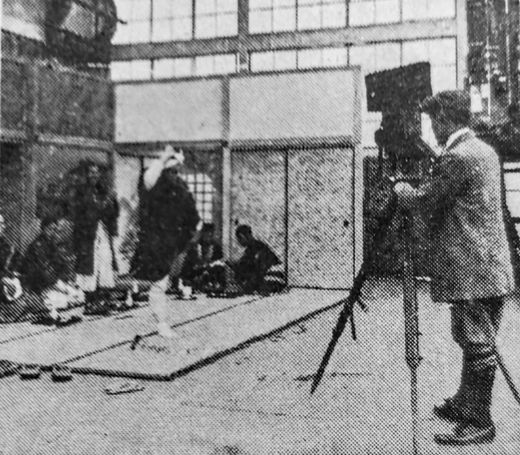

Japan was in some senses ahead of the West in terms of longer, more plot-developed movie production in the 1910's, creating some of the first complex one-against-many combat action scenes (as those by Onoe Matsunosuke 1875-1926, affectionately known as 'Eyeballs Macchan' for his expressive eyes), and employing drama techniques from Kabuki---which that pioneer of modern film technique, director Sergei Eisenstein, considered vital for the development of modern cinematography.

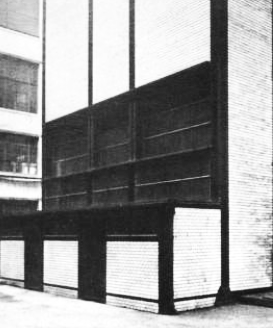

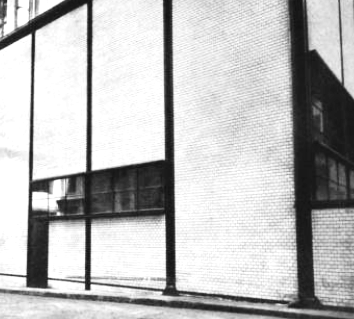

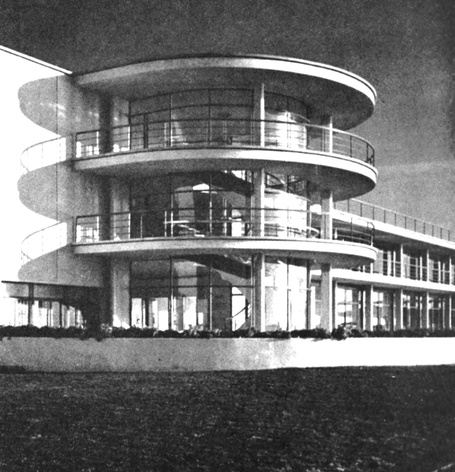

From an architectural perspective, while glass structures in an ornate Victorian Gothic style were not uncommon as exhibition buildings in England, large scale Japanese movie studios of the time remind one of strictly geometric glass facades of modern buildings that would only come to be seen in the West decades later.

Regarding the influence of Japanese aesthetics on the development of cinematography, see Daisuke Miyao, Japonisme and the Birth of Cinema, Duke U. Press, 2020).

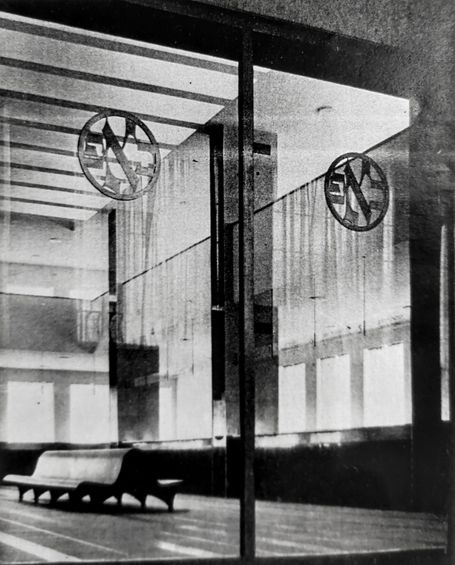

Below, from left: exterior of Kawaura Kenichi designed Yoshizawa Shoten Meguro Satsuejo (movie studio), Tokyo, 1908; the same, interior, filming scene, c. 1910; Kawaura Kenichi and Yoshimoto Keizo, Nikkatsu Mukojima Glass Studio (movie studio), Tokyo, 1913.

________________________

Uploaded 2023/5/27

Under Construction

Draft Preview

'Le Corbusier'

Japonisme

&

The Apotheosis of Charles-Edouard Jeanneret (1887-1965)

Yasutaka Aoyama

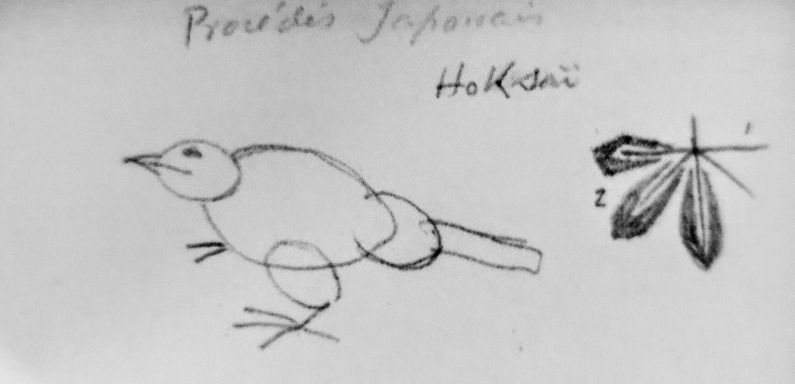

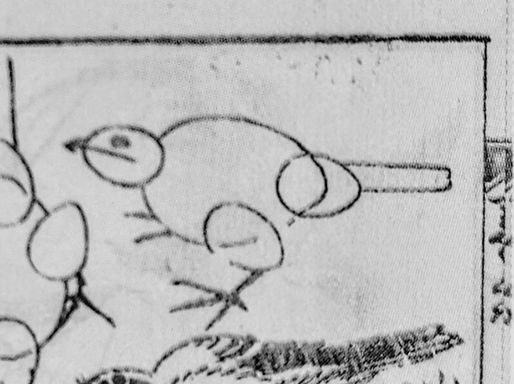

Japonisme after 1915

Japonisme in Europe was influenced by the coming of 'The Great War', as almost every aspect of society and thought was, from religion to politics, from propaganda to the philosophy of aesthetics. A different awareness of the world---and of themselves---gripped Europeans; the tremendous angst and disillusionment with European civilization is well-documented. That it became an age of soul-searching, a groping for new sources of rejuvenation was apparent to all. And that it had to appear as something refreshingly different from what was relied upon in the past---this also, was implicitly understood.

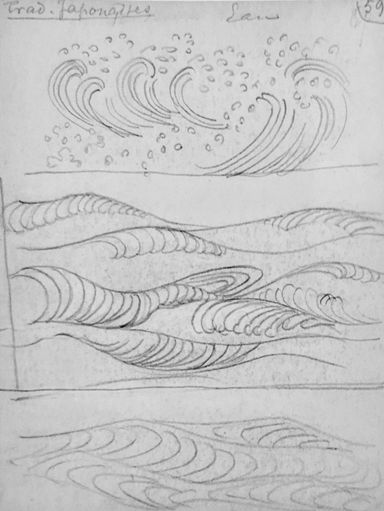

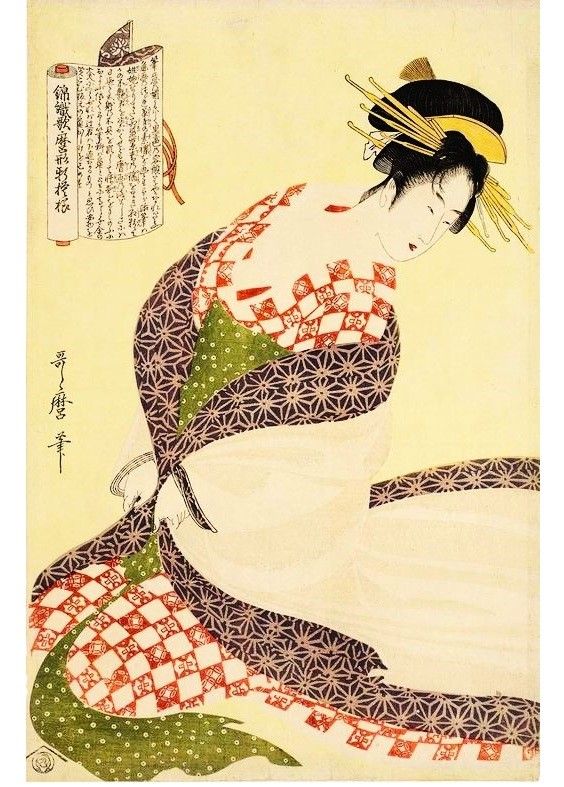

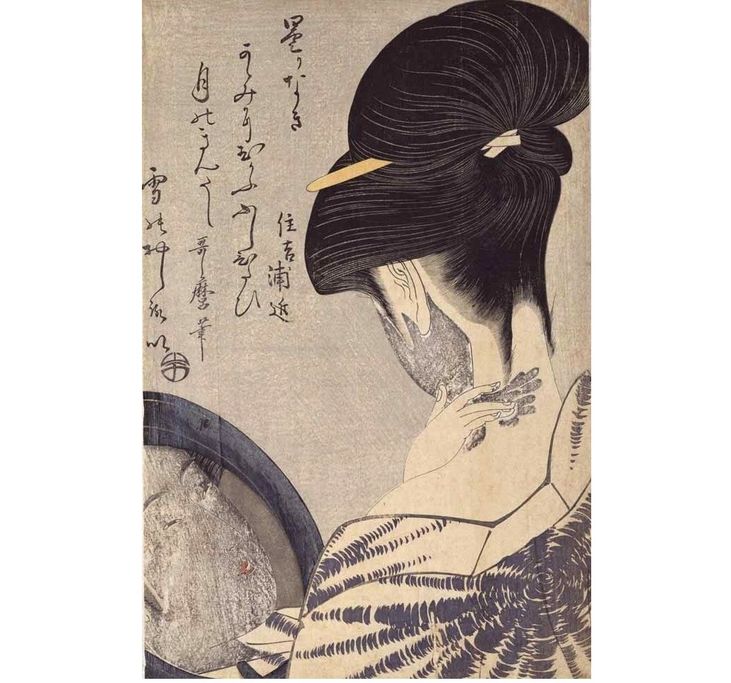

Idealized and uncritical appraisals of other cultures diminished; japonisme too, was old, and from 1914, the frilly sort of fad for Japan among the general populace started to dissipate. The sources of japonisme also changed. From ukiyo-e prints being the major source of japonisme in the 19th century, in the 20th century, the scope widened, encompassing lesser known arts and crafts and becoming inclusive of new forms of media, such as recorded film and music. Japonisme became a less obvious force in art, but nevertheless still an important part of the modern artist's 'arsenal', to use Klaus Berger's term.

Creating 'Le Corbusier'

In such an intellectual environment, artists claimed an originality springing from new social or technological forces in society, and of course, most importantly, from their own creativity. Art was considered more and more an expression of purely personal impulses, and something to be understood by "intuition", to use Benedetto Croce's (and Henri Bergson's zen-congruent use of the) term. While art from colonies around the world poured into European collections as 'artefacts' and 'specimens', the overt reliance on other styles or the aping of other cultures, by definition, became frowned upon in an atmosphere of continuing social Darwinism, further bolstered by trends in 'scientific' eugenic research; and as in political thought, the superior man, his unique genius, was exalted in all fields.

Certain artists, more so than others, became adept at cultivating their own reputations in the media, while relying upon talented workers under their aegis. Le Corbusier (Charles-Edouard Jeanneret, 1887-1965) was one of those particularly adept at doing so, ensuring that he gained the lion's share of the credit for co-produced designs, and successfully cultivating what might be almost called a cult of personality. As Jean-Louis Cohen writes in the introduction to Le Corbusier, Le Grand (Phaidon, 2006): "Le Corbusier was a real media star: for almost six decades he never stopped mobilizing the press, radio, and film in support of his ideas and schemes." And as Cohen relates, in a 1926 letter to Josef Cerv, Le Corbusier wrote of himself in the third person:

"Le Corbusier is a pseudonym. Le Corbusier practices architecture, exclusively. He pursues unbiased ideas. He has no right to entangle himself in betrayals, in compromises. He is an entity freed from the weight of the flesh..."

Thus Le Corbusier refers to himself as an entity transcending normal humanity, in what sounds like self-proclaimed apotheosis. Meanwhile, that is at the same time, "Ch. Edouard Jeanneret is the man of flesh and blood, who has had all the radiant or heartbreaking adventures of a pretty eventful life." Or so says Le Corbusier in the same letter. Is this not a vision of Superman and Clark Kent, or some other comic book fantasy? If it were anyone else, it would probably be diagnosed as an authentic case of a patient possessed by serious delusions of grandeur.

Even today, no questions or doubts are raised at Charles Edouard's self-ordained appellation as 'Le Corbusier' with its faint connotations of being a master craftsman or maker of some kind; yet it no more a real or legal name than Benito Mussolini's political version of the same, also preceded by the definite article. This oddly blind acceptance of his unique position by critics and the public has meant that not only Japanese influence, but all obvious precedents in terms of ideas, such as those of Otto Wagner, or designs, such as those of Adolf Loos, have been downplayed in discussions of 'The' Corbusier.

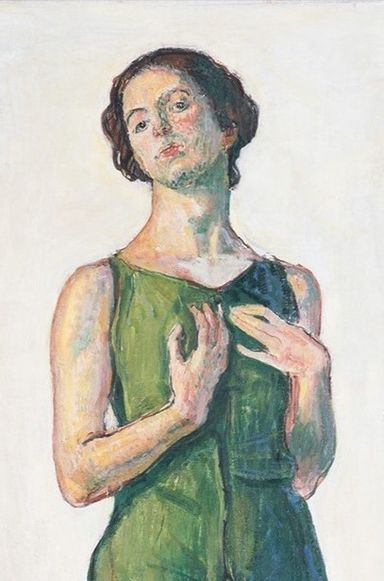

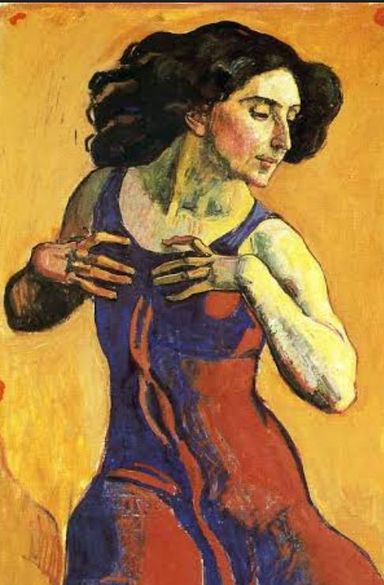

Sigfried Giedion, chairman of the Harvard Graduate School of Design, whose Space Time & Architecture was for years the closest thing to a bible for students of modern architecture, played an instrumental role in solidifying the pantheon of architectural heroes with Le Corbusier at its pinnacle. Le Corbusier is the equal of Michelangelo, Raphael, and Bramante; and quoting none other than himself, Giedion says: "an all-embracing genius: an architect, painter, and urbanist with the vision of a poet". Yet if Ch.- E. Jeanneret were not an architect, could his painting (which either reminds us of previous works by Picasso or Braque or Leger and at times even Klee and Chagall) or his 'poetic urbanism' stand on its own? Giedion's adulation and adoration of Le Corbusier had no bounds. The man is a prophet of the age, fighting obstruction, misunderstood, and psychologically persecuted--almost a martyr; and we hear in Giedion, perhaps more of Giedion himself than the reality of another individual; the fulfillment of both a religious and at the same time a rather Nietzschean or Spenglerian ideal, just as Le Corbusier himself would have wished. Looked at in the cold light of day, however, there is no questioning that Le Corbusier was also the champion of large scale, organized industry, providing the perfect justification for furthering mass production with his ideas of architecture as building "machines for living in".

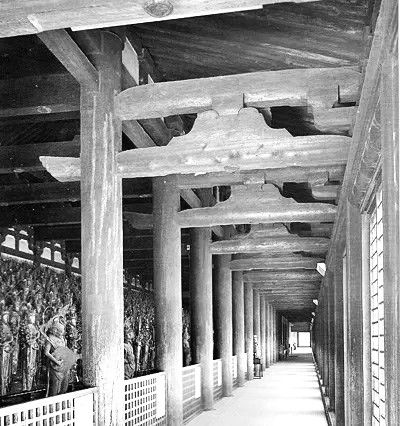

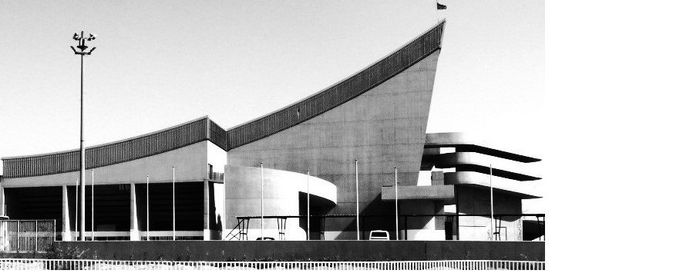

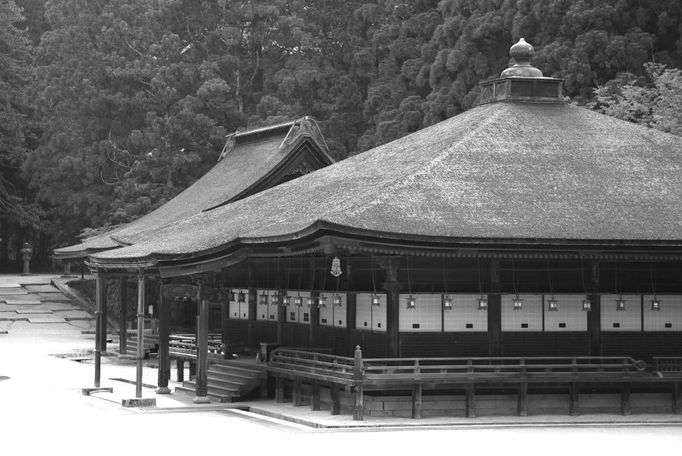

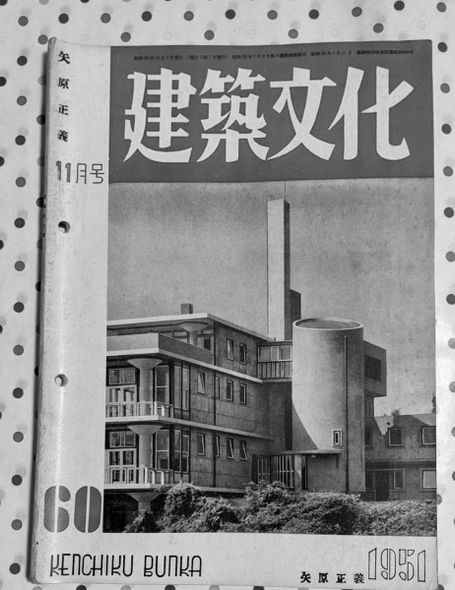

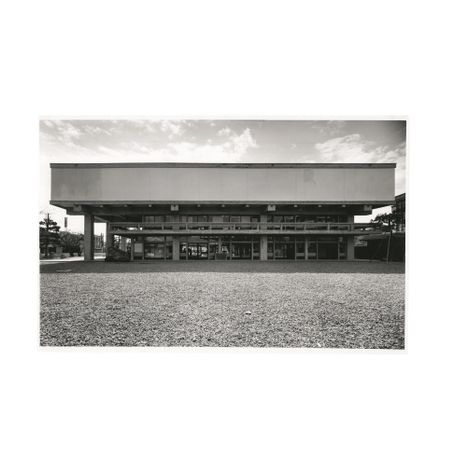

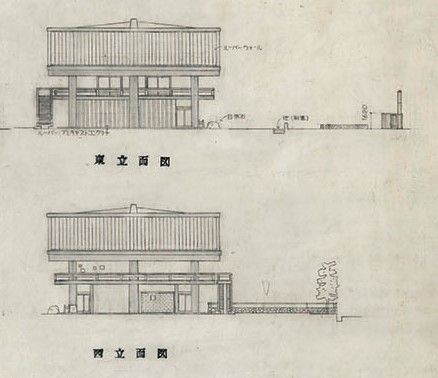

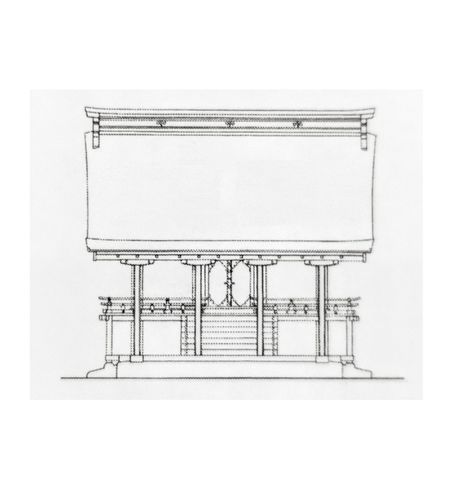

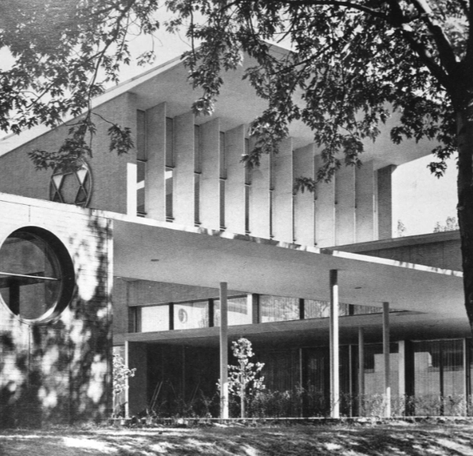

That the nature of Le Corbusier's reputation is cultish to this day, of an almost religious nature, can be seen in the promotion and elevation of his works, even his lesser designs to special status as UNESCO World Heritage Monuments, even when there are other works in those countries which are of a more original or irreplaceable nature. For instance, Le Corbusier's National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo opened in 1959 when modernism was already ripe, would likely not attract as much attention were it designed by a different architect; Sakakura Junzo's Museum of Modern Art in Kamakura which opened in 1951 is a more significant work in that sense. Or for that matter, the Sanjusangendo Temple (1164 rebuilt 1266) in Kyoto, discussed below as a possible source for Le Corbusier's Chandigarh, is certainly an irreplaceable and more worthy candidate for historical preservation than the Tokyo museum. In the final analysis it is simply the 'brand' of Le Corbusier that has become the determining factor, just as anything done by Picasso is considered museum material regardless of content or composition date.

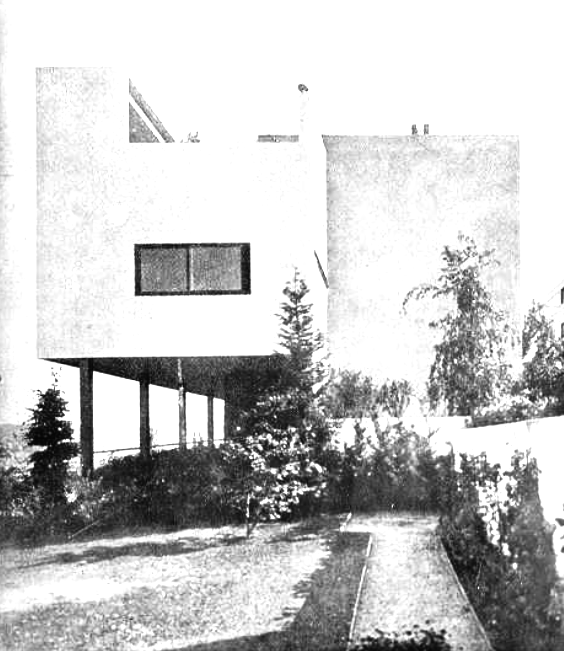

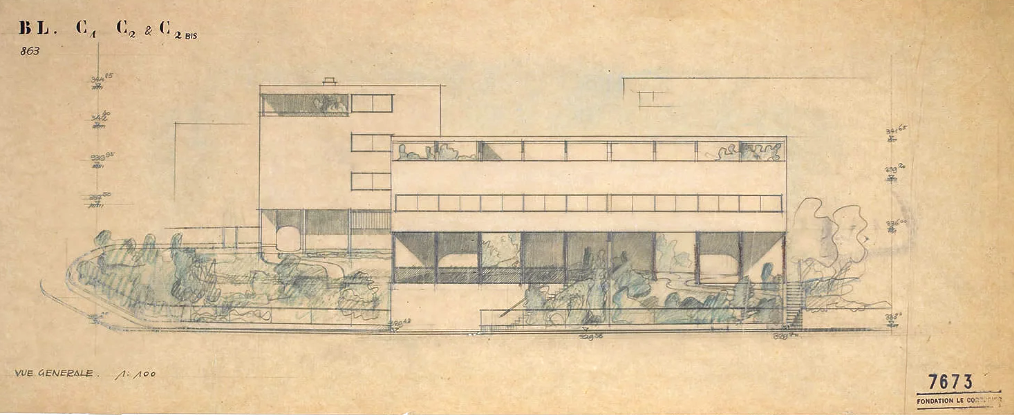

Quintessentially Japanese

The lionization of Le Corbusier started in his lifetime and his worldwide celebrity status was firmly established by the 1950's, growing stronger with every passing decade. In such an environment, Siegfried Wichmann, in his monumental Japonisme: The Japanese Influence on Western Art Since 1858 (1981), was courageous enough to point out the obvious when he stated that the Villa Savoye "gives a sense of modular flexibility inherent in the Japanese tradition of building on stilts" and that in the case of the Salvation Army Hotel (Cite de Refuge) the "modular divisions were anticipated in Japanese construction methods."

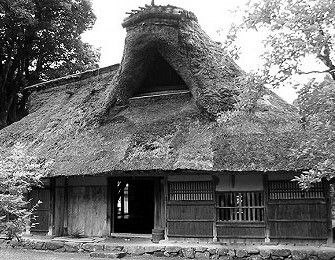

Yet he stopped short of carrying his observations further to their logical conclusion, that in almost all respects conception and detail are combined in Le Corbusier's designs as they are found in Japan. The key difference being two only: Roofing and construction material. The former is removed and becomes unessential due to the second, i.e. concrete which replaces wood. Stated differently, a traditional Japanese house, made in concrete and 'de-roofed' would be in an architectonic sense identical in most respects to Le Corbusier's architecture. Or otherwise put, if Le Corbusier's designs were built with wood and roofed, many of them would be in essence simplified versions of Japanese architecture.

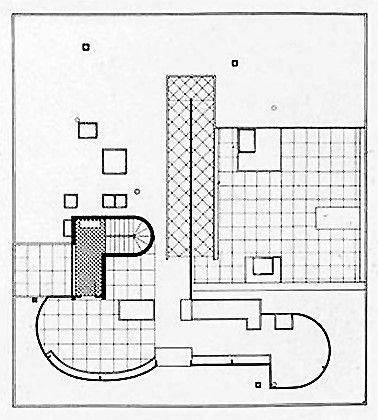

Les cinq points de l'architecture moderne, 1927

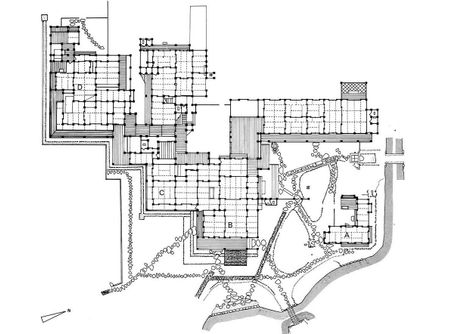

Of what are often referred to as Le Corbusier's 5 points, 4 are clearly essential ingredients of traditional Japanese architecture, commonplace and found in the combination that Le Corbusier outlines: 1) 'pilotis' (weight supporting hashira), 2) an open, free floor plan, 3) long windows and 4) open and freely designed facades.

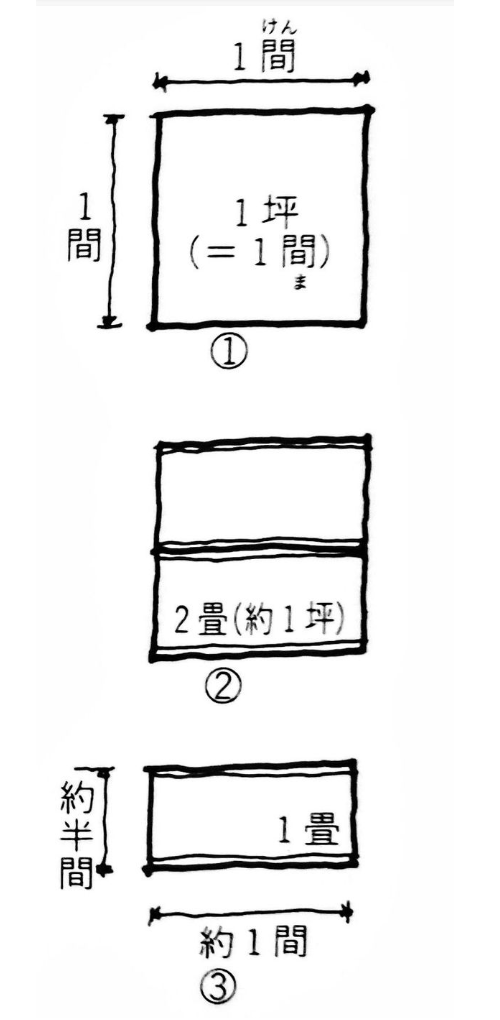

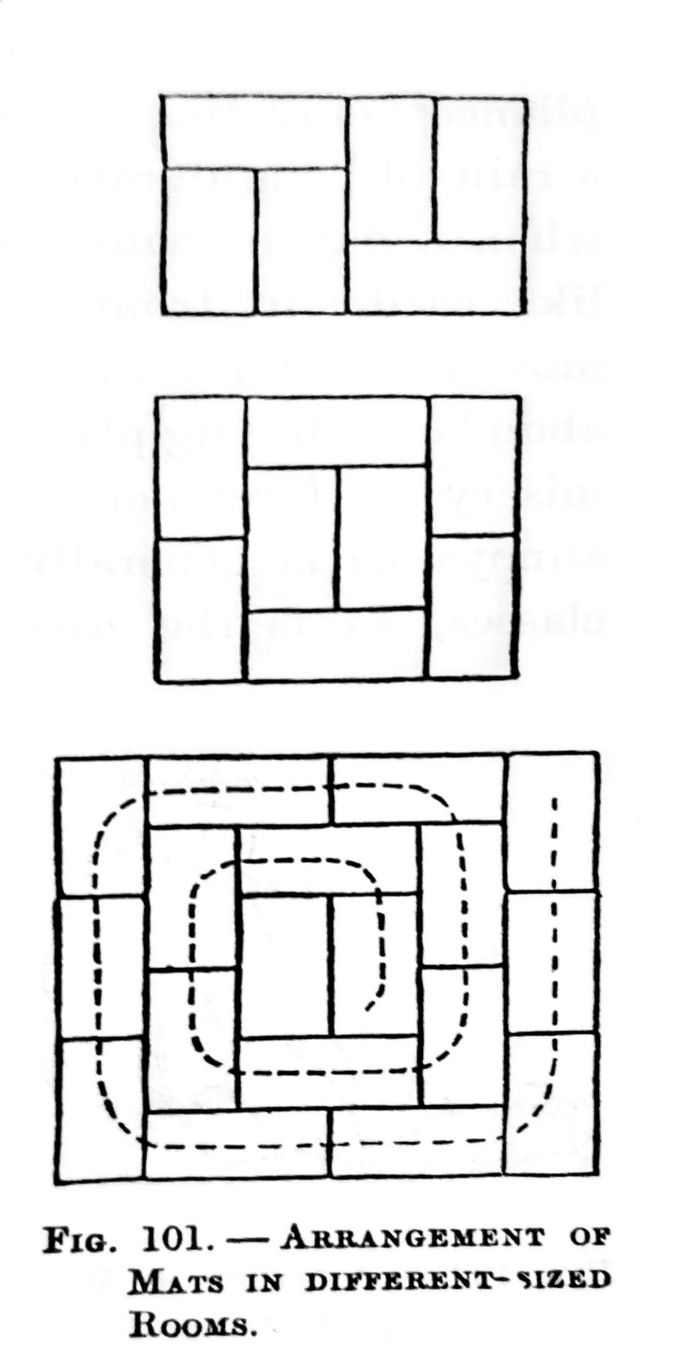

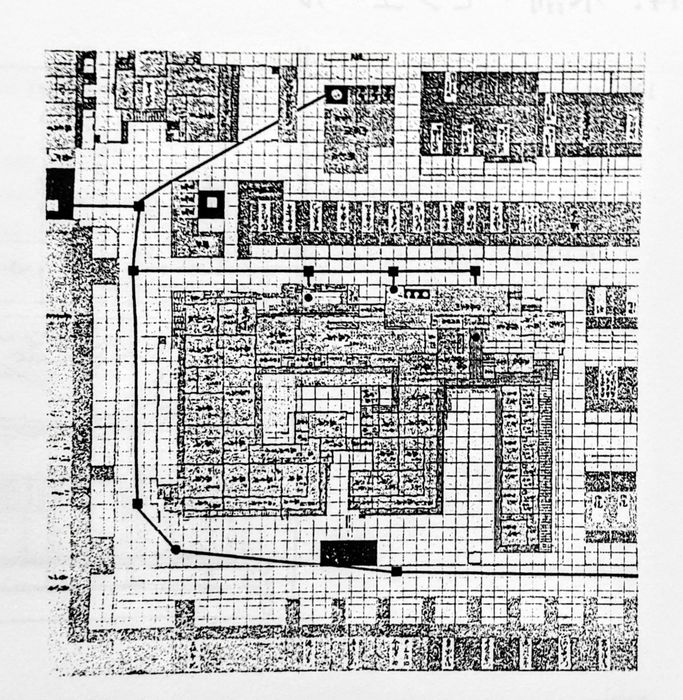

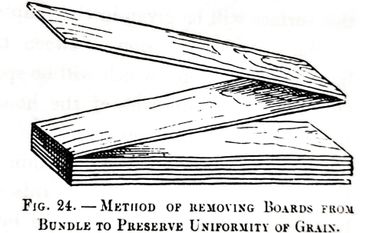

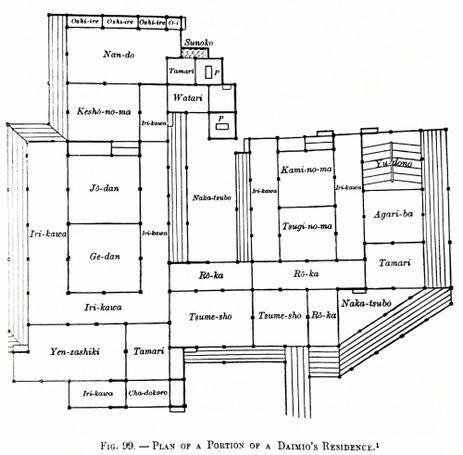

Furthermore, his concepts of the 'modulor', an rectangular unit of measure that is to be applied throughout a building, reflecting a basic ergonomic spatial size, that becomes the basis of larger key units of construction, is precisely what the tatami or 'jo' of Japan is, which when added with another becomes the 'ken' in length and 'tsubo' in area, and is likewise applied as a standard unit of measure that ties in with the plan and elevations. Building was based on standardized 'kiwari' or timber splitting measurements which were integrated with the ken/tsubo into one system. Furthermore, traditionally, the plan of a Japanese house was done on a grid which reflected these measurement criteria, and designed accordingly -- ideas which are reflected in ideas about construction in modern architecture, with of course a switch in building materials.

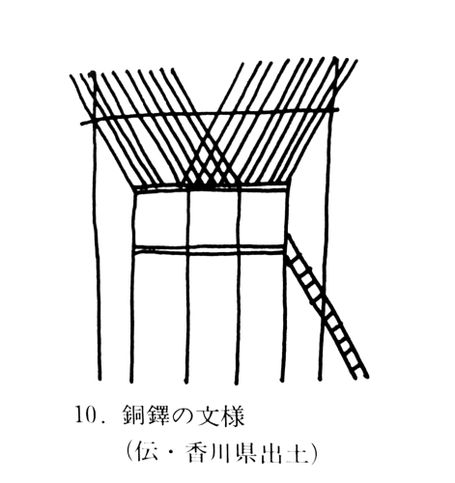

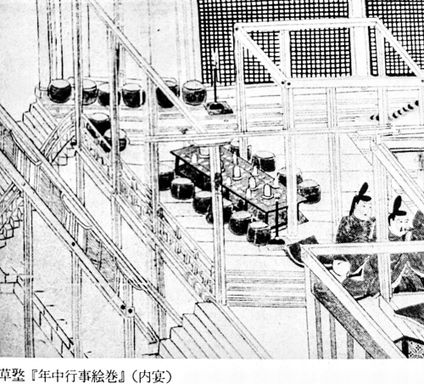

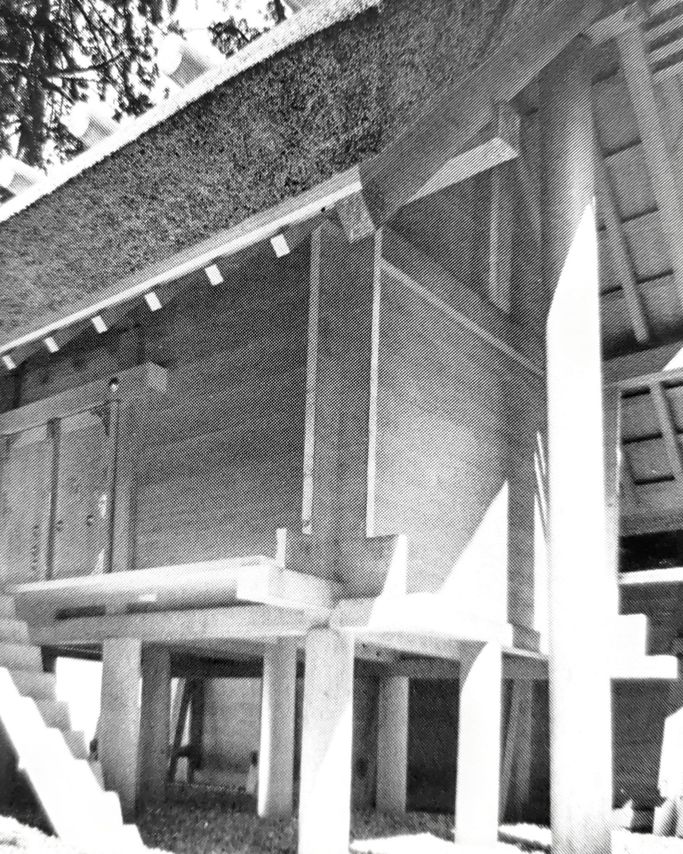

The Domino House, which is thought to encapsulate Le Corbusier's most fundamental structural principles, has another key feature of traditional Japanese architecture: the raising of the house on stilts, or 'takayuka' construction, leaving a ventilation space underneath for residences. Much higher raised floors can be found in Shinto shrines and in ancient storehouses such as the Shosoin of Nara (which may be meaningfully compared to his Ahmedabad Museum, 1951). For Japan, the raised floor is not only a familiar architectural feature, depicted in prehistoric bronze bells and pottery or thousand year old picture scrolls known as emaki, but an established part of Japanese literary, dramatic, and early cinematic culture as a place of hiding, eaves dropping, and at times even dialogue.

The roof garden is the only one of Corbusier's five points that is not traditionally Japanese, though roofs completely covered with moss or purposely planted with grass did commonly exist in Japan, called 'shibamune' (芝棟). And the idea of a garden as one with house design, that a house be integrated with nature, rather than imposed upon it is a Japanese conception, which Le Corbusier has incorporated vertically as opposed to what was often perceived as horizontally in the case of Japan. But in fact traditional Japanese architecture is integrative both horizontally and vertically with its natural environment. The idea of architecture that accommodates a tree into its design, can be seen not only in house designs with plans which avoid existing trees, but shrines for instance, where roofs have apertures for the trunks of trees.

While not being a feature of traditional Japanese architecture, the first rooftop gardens on modern buildings in fact, are Japanese, built decades before Le Corbusier espoused the idea. It maybe worthwhile here to briefly go over the facinating history of roof gardens in Japan, to gain perspective on just how well established the idea was before Le Corbusier's 'Five Points'.

Starting in the early 1860's (1861-1864), at Chukushima (Hakodate, Hokkaido), Musashino Seijiro built a pleasure pavilion or 'giro' (妓楼), his 'Musashino-ro', a three storey building of which on the second floor roof a garden was built, depicted in Utagawa Kuniteru's print 'Hakodate Toyokawacho Musashino Sangaizukuri Zensei-no-zu' (1873), which even included a pond, and approximately covered a 100 square meters. It seems from this point on more and more roof gardens were built, and for foreigners as well, such as that of the importing and provisions company, Langfeldt & Mayers, in Yokohama (1881).

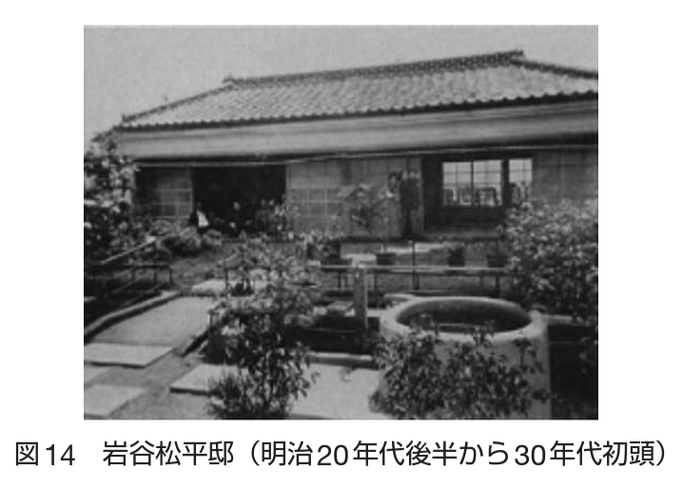

In the 1890's there are records of 'Tabacco King' Iwaya Matsuhei's combined personal residence and store and its sprawling rooftop garden in central Tokyo, which was eventually equipped with a pump driven waterfall, as mentioned in a 1901 tabacco advertisement. Around the same time, Hattori Choshichi, in the construction business, built a rooftop garden for his mansion in Ginza, some time before 1896, since his roof garden appears in publications from that time on. It was a complete, Japanese style garden, with a pond, tourou stone lanterns, stepping stones, and of course extensive plantings. Perhaps stimulated by Hattori's rooftop garden, the Nihon Engeikai Zasshi (Japan Horticultural Society Magazine) started to routinely use the term 'okujo teien' (rooftop garden 屋上庭園) from 1896 onward. (Kondo Mitsuo, 'Wagakuni ni okeru okujoteien no kigen to reimeiki ni okeru tenkai ni tsuite' Zoen Gijutsu Hokokushu, 2009)

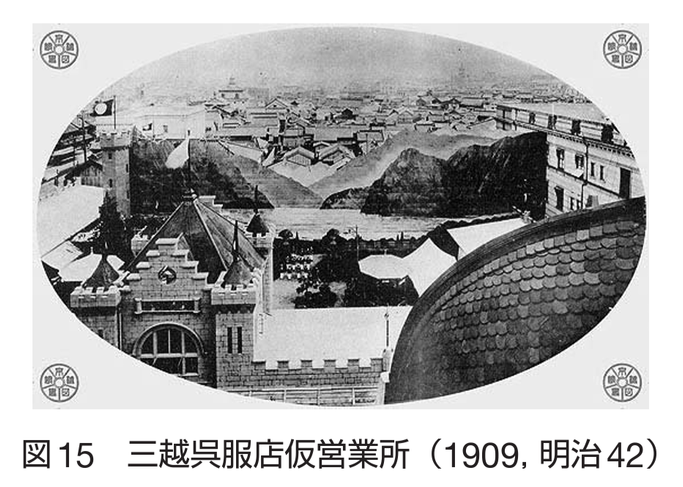

The history of rooftop gardens on modern concrete buildings, however, started in 1907, with the Oriental Hotel of Kobe (catering largely to foreigners) building a rooftop garden for its guests and the Mitsukoshi Department Store in Nihonbashi (central Tokyo) building the first 'Kuchu Teien' or Sky (or Aerial) Garden ( 空中庭園 literally mid-sky garden), which eventually had a fountain, pond, hanging wisteria racks, large numbers of bonsai and other plants, and even a small shrine (Mimeguri Inari) and tea house, covering a total area of almost 200 square meters.

Actually 4 years earlier, in 1903, also in Nihonbashi, the Shirokiya Department Store had built a amusement park on the roof, which was primarily oriented towards children with see-saws and rocking horses but also had a bonsai display (bonsai chinretsu) section and 'pure drinking water' (seiryoinryosui) fountain; however the Mitsukoshi garden was the more full fledged rooftop garden on a modern department store. The Matsuya Department Store at Kanda (Tokyo) built a competing rooftop facility later in the same year, and in quick succession other department stores followed suit, each providing novel features; several years later rooftop gardens appeared in the Kansai region, such as the Kyoto Daimaru Department Store rooftop garden (1912). These gardens expanded in grew in size in the following years to cover extensive rooftop areas. This was much earlier than anywhere in Europe; for instance, the first department store rooftop garden in England was the Kensington Roof Gardens in London which opened in 1933.

We have focused on department stores, but by the early 1920's, in the years just preceding Le Corbusier's proclamation of the roof garden idea, gardens on rooftops were becoming quite common in major urban areas in Japan, appearing on a variety of buildings, including apartment buildings. (See Tsukano Michiya; Sendai Shoichiro, 'The Roof Garden in Japanese Modern Architecture: From the Meiji Period to the End of World War II' Nihon Kanseikogaku-kai Ronbunshi, Vol. 13, No. 1, Tokushugo (2014) pp. 127 - 135. Photos immediately below from the same article.)

Poster for the rooftop 'Daimaru Garden', c. 1920

Photo of Matsuya Department Store of Asakusa, Tokyo, with its mammoth rooftop garden and amusement park built in 1931

Thus even Le Corbusier's idea of a rooftop garden, may have taken a hint from trends in Japan. In any case, this probably is the least important of his 5 points, because it is not always present and is not as interdependent with the other principles as the others are with each other. The roof garden is a preferential feature, but not an omnipresent necessity to the working of his system, a point which Le Corbusier himself seems to have understood, occasionally treating a garden as almost an afterthought to be 'shrubbed up' by others, simply given a place to be. If it were of equal weight to the other points, he would have probably designed more detail into them, but in certain cases there is little specificity in his garden designs besides a few nondescript planters as in the Dojunkai Apartment House in Harajuku, Tokyo (lower right of black and white photos shown above).

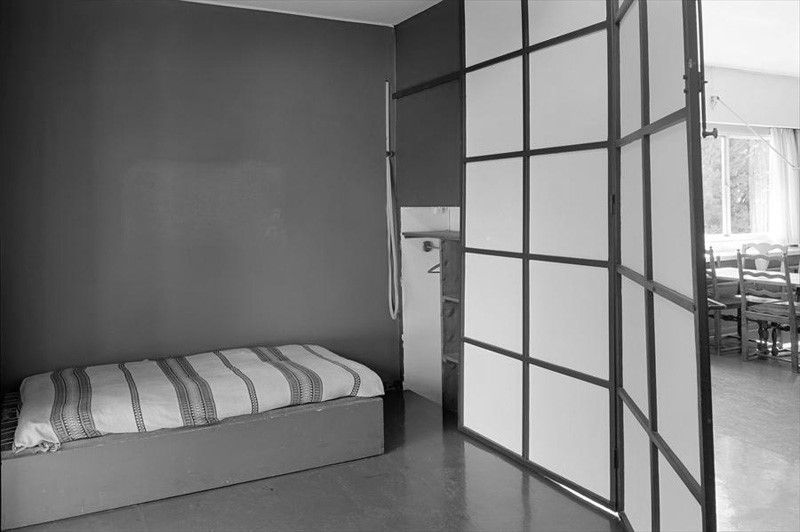

The essential architectonic ideas of Le Corbusier are the other four, plus two (a foundational unit of space and raised floors) which are also necessary in describing Japanese architecture -- principles without which, traditional Japanese architecture would not be what it is. Furthermore, even key aspects of surface and interior detail that are not directly a result of the '4 plus 2' are rather Japanese in nature: the surface geometries and interior design, for example the repetition of rectangular grids in the interior, and the low center of gravity of the furnishings.

Not to call attention to these facts, and to avoid all mention of Japan in discussions of Le Corbusier's designs in Europe, would be much like describing architecture in Asia that was 1) centrally fronted with columns topped with a triangular decorative space above; 2) had equal length wings on both sides with walls punctuated by upright rectangular windows with thick decorative framing at equivalent intervals; 3) a symmetrical box type floor plan; 4) walled off rooms with openings only large enough for one person to pass through, equipped with newly named 'doh-ah' -- flapping, hinged planar devices to close rooms; and finally, 5) a basement pool -- something surely not a standard feature of Western architecture; and thereby tout it as a purely original conception of 5 key principles (and also thanks to it being constructed let let us say, in plastic rather than stone or concrete)!

Preposterous as it may seem, this is much like the proposition accepted today, that Le Corbusier's designs and his design principles are unrelated to those of Japan.

Japanese Precedents for a Modular, Measurement Systems Approach

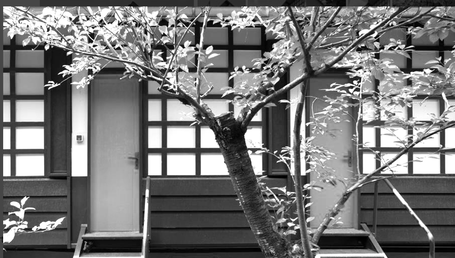

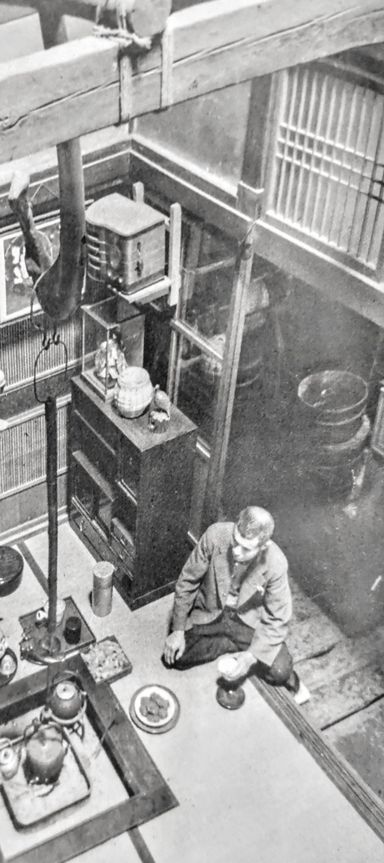

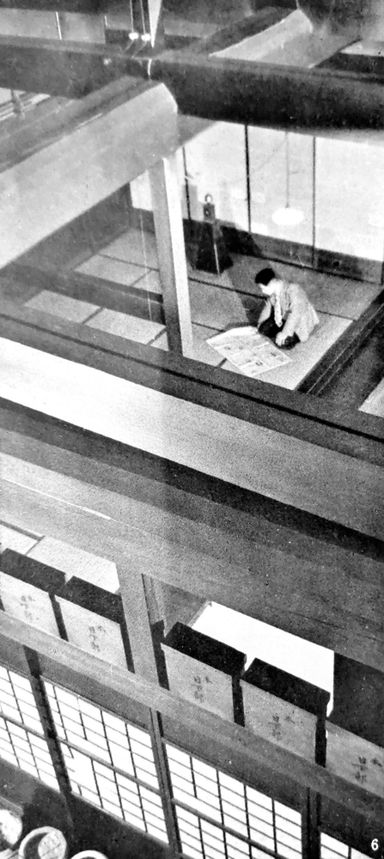

Living á la Le Corbusier in 19th Century Japan

Below: Examples in Japan of open facades, free floor plans, long windows, weight supported by exposed piloti--i.e. hashira, and floors raised from the ground on stilts. As shown in the photos taken by European photographers from the late 1860's and early 1870's, the ideas of Corbusier were already actualized, experienced, and documented by Western expatriates in Japan in the 19th century. While the photos below are those by Michael Moser, Wilhelm Burger, and Felice Beato, there were many other such photographers of Japan, among whom the Swiss Pierre Rossier (1829 - 1886) was one of the first, capturing many images of Japan a decade earlier between 1858 - 62. And from 1900 onward, with the international postal system in place and the printing of picture postcards in Japan, photographic and painted pictures of Japanese architecture, often with English language descriptions, were sent or brought back home by Western tourists in fair abundance. The low lounge chairs (visible on the left in the photos) of the British consulate, most likely designed and produced locally, are very much the kind of chairs that would become known as 'Modern' in the next century, five decades later.

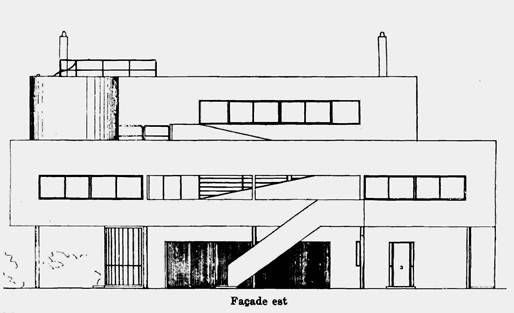

Below: Photo by Felice Beato, Japan,1860's with Le Corbusier's Villa Savoye at Poissy (1928-1931), for comparison under it. By the late 1860's the use of glass in shoji sliding panels in mid-section was common. Here, on the ground level, the shoji panels are partially open, but when slid shut (and as the shoji were papered in white) look exactly like Le Corbusier's ribbon windows on his Villa Savoye. As the same was done also on multistorey buildings, the effect was even more modern. Note how we have here four of his key points: structural support by pillars only, an open floor plan, long windows, and a free facade. And furthermore, it is raised from the ground on stilts.

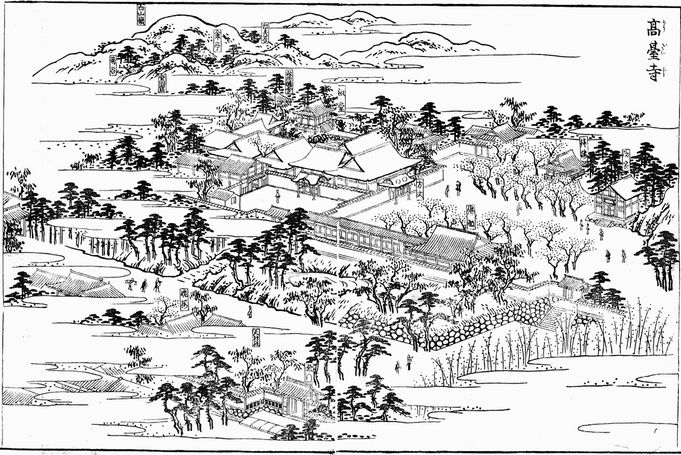

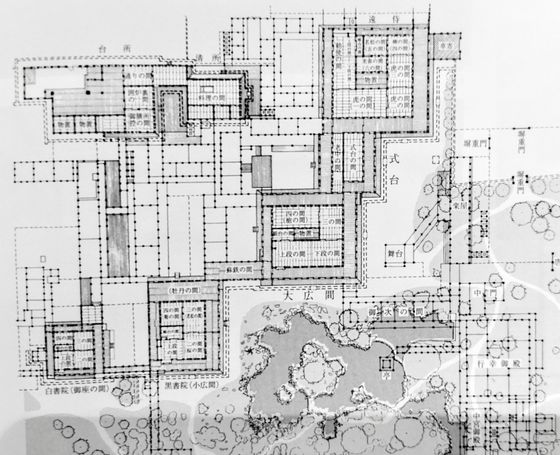

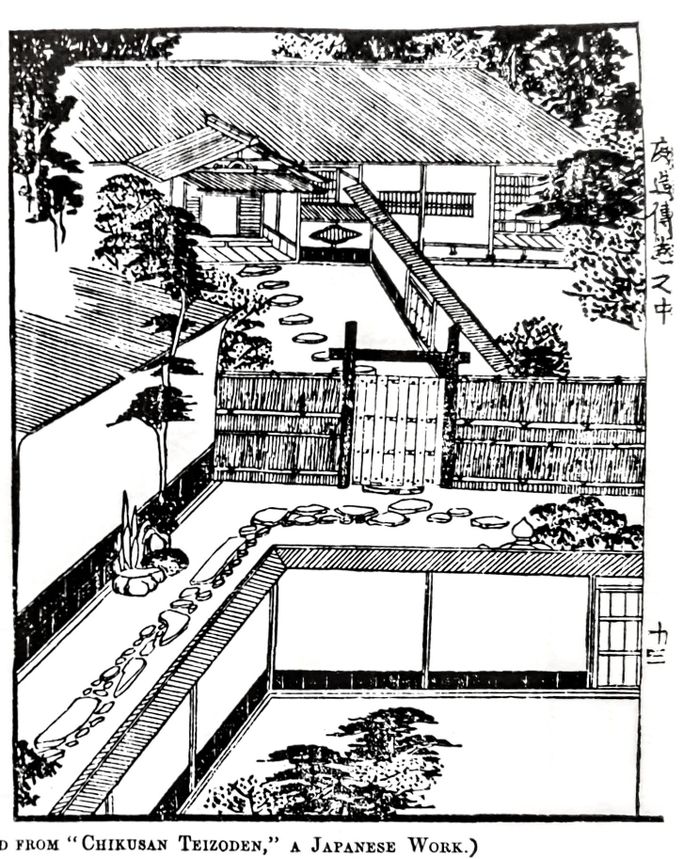

Japanese Floor Plans and the Horizontal and Vertical Harmonization with the Environment

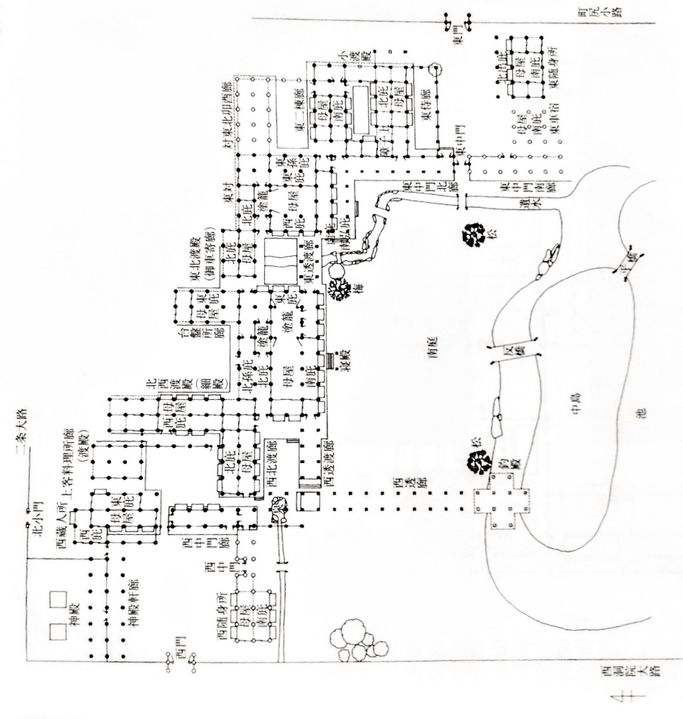

Below: Freely extending, open floor plans, horizontal and vertical integration and harmonization with nature in Japanese architecture. Left: Kodaiji (Temple), Kyoto, early 17th century. Center: Tateriko Shrine, Nara. Right: Plan of Nijojo (Castle), Ninomaru-goten, 1603. Note how the irregular and sloping rooflines in the Kodaiji print below (left) blend in with not only the trees, but with the rhythm of the large and small hill peaks beyond. Le Corbusier's idea of rooftop gardens is congruent with this idea of integrating the roof with nature, which until then in the West, as in the case of palaces or Gothic churches, had been more of a device to stand out from, or reach higher and surpass nature.

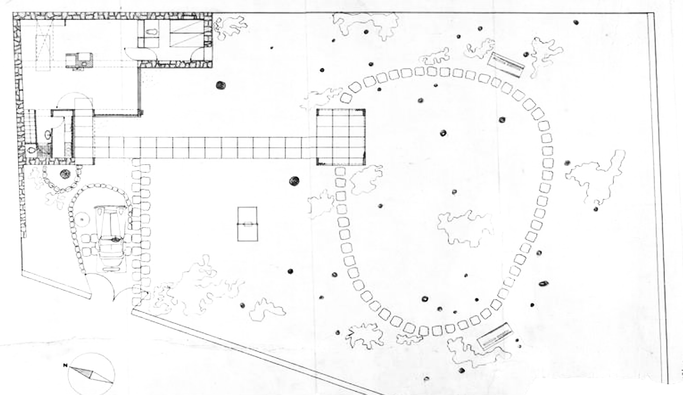

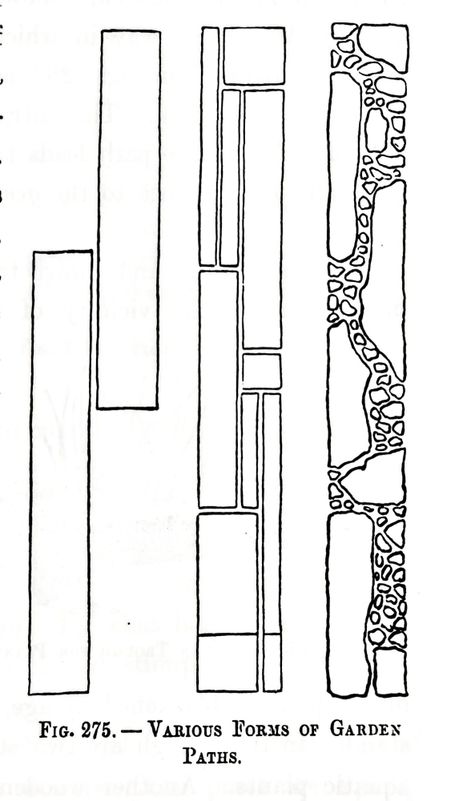

Below: Left, photo and plan of Maison de week-end, La Celle-Saint-Cloud, France, 1934. Right, plan of Higashi Sanjo-den, Nara, 1043-1166, an example of a classic layout for Japanese shinden style villas, with an extended walkway ending in a tsuri-dono, or fishing pavilion. Note the similarities of enclosure, the situating of approach and entrance, the basic divisions of site space, the staggered free plan, and the long, straight extensions from the house into the garden, ending with a structure jutting into a clearly defined space. Various residences and temples ever since the Heian period have been modeled upon this basic conception, which is somewhat reflected in the layout of Kodaiji above, and which Alvar Aalto also may have emulated. Other points of interest include the stepping stones, visible in the photo of Le Corbusier's week-end house below, which combine straight paths made of large rectangular stones connecting with curving paths of paired stones, standard in Japanese garden design, the most famous example being the Katsura Villa in Kyoto. Traces of where a Japanese pond would have been can be seen in the placement of stones that outline a pond shaped area in Le Corbusier's plan.

Architectonic Equivalence

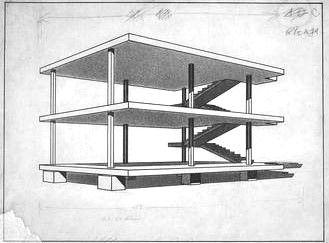

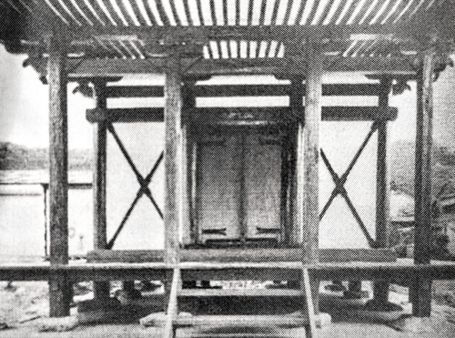

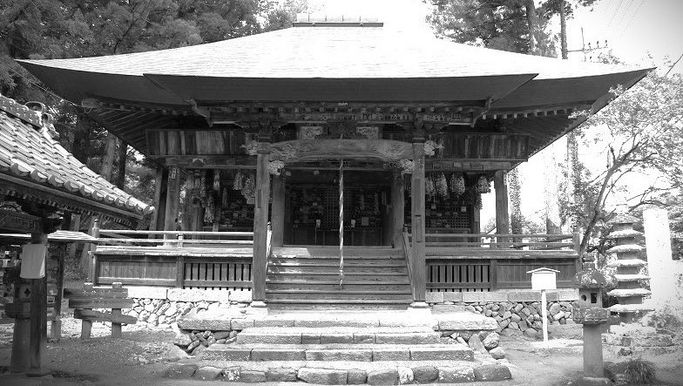

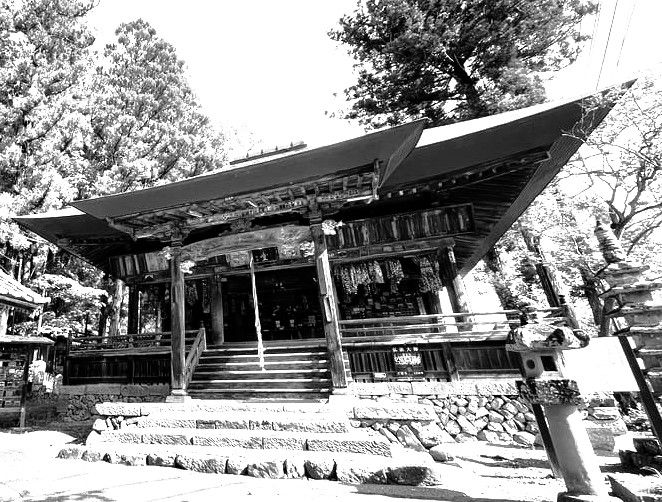

Below: Left, Tea House, Negishi, Tokyo. Center, Le Corbusier's Domino House. Right, Yamada Daio Shrine. If replaced with a flat roof, architecture in Japan is structurally analogous to the Domino House, excepting the building material. Even the simple stairway off to the side and somewhat back (unlike in Western architecture where the stairway was given a place of prominence, traditionally in the entrance hall), is a common feature of Japanese multistorey architecture.

Similar architecture was built repeatedly for expositions from the latter 19th century onward, such as the Japanese Satsuma Pavilion at the Universal Exhibition in Paris of 1867, shown below, left. Though not shown here, perhaps the tea house of the Paris exhibition of 1900 is even a more apropos example, being comprised of two floors supported by pillars with a stairway in the back, the front and sides almost wall-less. These expositions which continued into the 20th century were heralded as prominent events that would likely have caught the attention of Le Corbusier since his early days, and photos of the exhibit buildings were not uncommon. The partitions in the Satsuma Pavilion are sliding and removable, thus making the space virtually identical to that of Le Corbusier's. But of particular interest is the Japanese house of Hugues Krafft at his expansive Midori no Sato Gardens near Versailles, built in 1886, which included even more features that would later mark the architecture of Le Corbusier, such as irregular floor plans and windows. A meeting place for renown Japanophile artists and intellectuals (visited by the likes of Marcel Proust), Gonse praised it in his publications, Felix Regamey in his book Le Japon pratique (1891), described it in detail with illustrations, and Albert Maumene published articles, with photos included, in 1909 and 1911 (Omoto Keiko, 'Hugues Krafft', in J.S. Cluzel, Japonisme and Architecture in France 1550-1930, 2018), all in the years Charles Edouard Jeanneret was gestating into Le Corbusier. In other words, whether he saw images of it or not, Japanese architecture was very much in the air in the 1890's to the 1910's in France, and in the minds of other men like Albert Kahn were dreams of also realizing the ideals of Japanese architecture.

Photo to the right: a model of the Domino House built by students at the Venice Biennale XIV (2014), which has become the largest international architectural exposition and gathering. What is interesting here is that the structure has been built in wood, thus partially reverting to and validating its prototypical origins. Wood is a better material, in terms of cost and ease of construction, and even durability, for building such a structure. Concrete is extremely heavy, and in fact, not as suitable for the Domino design which relies on relatively slender pillars. But concrete requires heavy machinery, mass produced concrete, and sufficient metal reinforcement to realize such a concept (beyond the capabilities of a small or self sufficient group), something Le Corbusier, who de facto had become an advocate of large scale heavy industry, seems to have found satisfying rather than problematic.

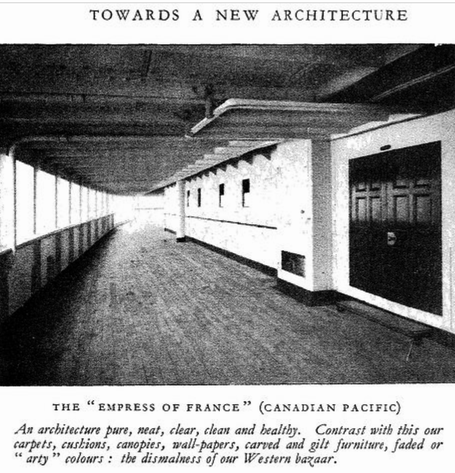

Again, as in his Towards a New Architecture, has not Le Corbusier simply created a pastiche of alternative images, from Greek temples to luxury cruise ships to convey what already existed as a design package in completed form in Japan for centuries, if not a millenium? Thus the term 'architectonic equivalence'.

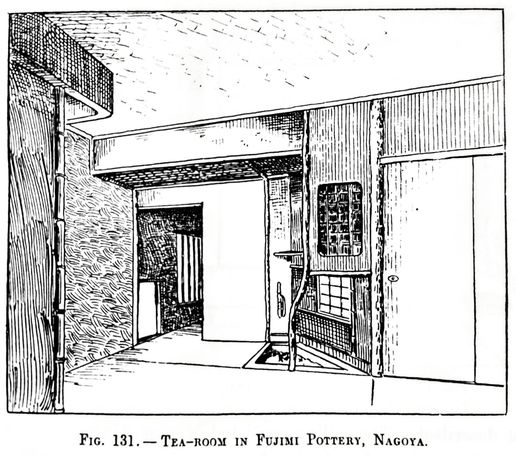

Tracing the Natural Evolution Towards Modernism in Japanese Architecture

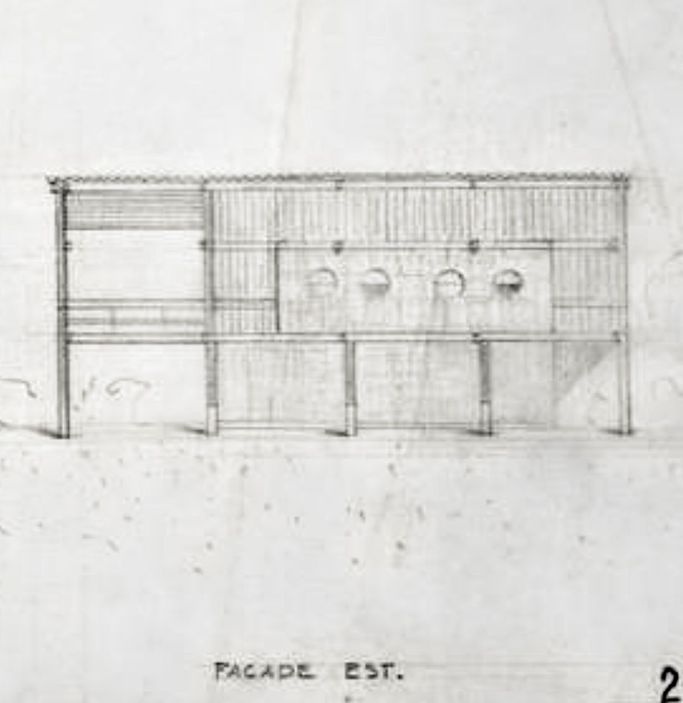

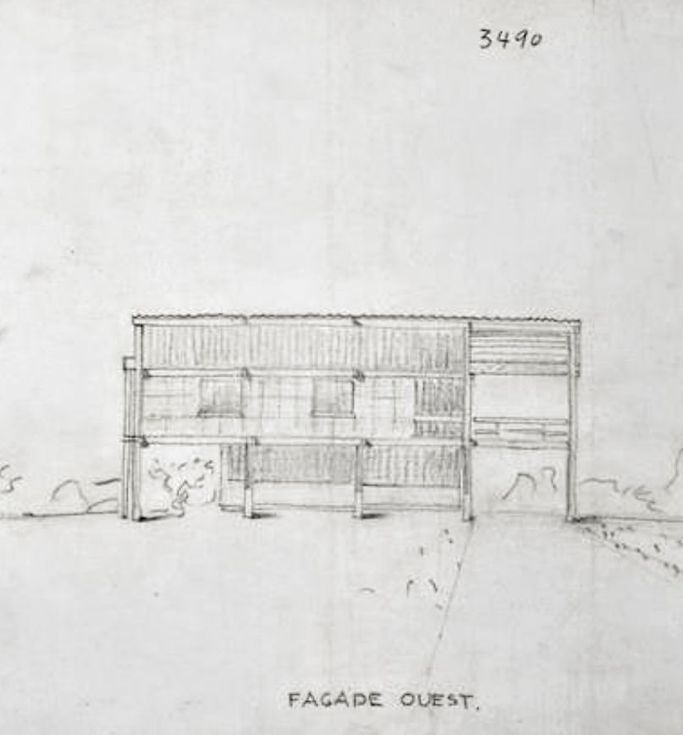

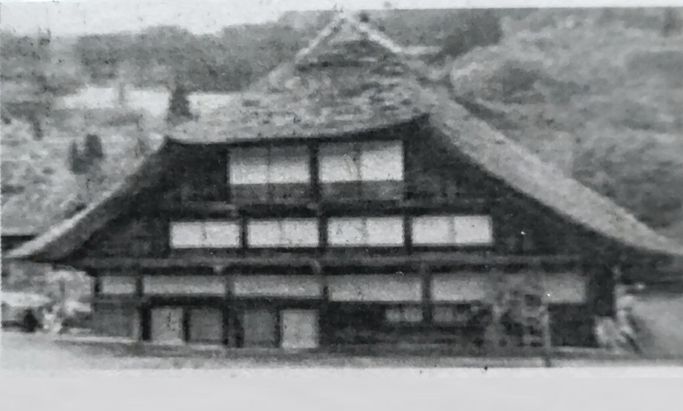

Regard below, left the Oji-inari no Chaya (tea house, Tokyo, photo from The Far East, a fortnightly paper, 1872); to the right, Le Corbusier's Maison du Docteur Curutchet (La Plata, Argentina, 1949). Note the basic, multilevel structural similarities between the two and the open to the air quality to both of them. Le Corbusier's Villa Baizeau (Carthage, Tunisia, 1928) also can be fruitfully compared to the Oji-inari no Chaya or other similar commonplace buildings of Meiji era Japan, such as onsen (hot spring) resorts of the time, such as the Notoya Ryokan of Ginzan Hotsprings (Yamagata) o rthe Yunoshima-kan at Gero Hotsprings (Gifu), with their multistoried, contiguous glass windows.

In the photo of the tea house, a similar 3 storey building in the background can be made out which is in a 1868 published photo collection of Felice Beato. From the Meiji Restoration onward building heights were not restricted as they were before which led to a great spurt in multistorey building.

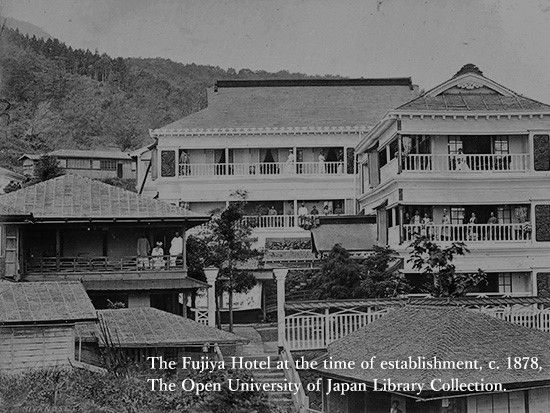

Hotels catering to Western visitors, as the Fujiya Hotel (Hakone, c. 1878) shown below left, showing a merging of Japanese and Western architectural features. The origins and evolution of open balconies from the traditional, smaller houses in the foreground into the larger hotel structure is apparent. To the right, one storey structures with open floor plans supported by piloti, and in the background, large floor to ceiling extending grid windows.

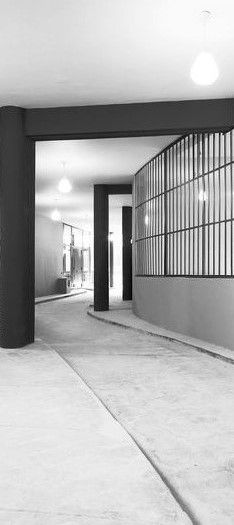

Below: left, the Foreign Engineers Residence known as the 'Ijinkan' (1867) in Kagoshima with Le Corbusier's Villa Savoye (1931) to the right. Note how key elements of the Savoye are already present in the Ijinkan: 1) the structure being raised and supported by piloti (pillars), 2) the second floor windows being wall to wall, 3) the wrap around balcony with the ground floor recessed on all sides, 4) relatively open floor plan with long rooms sometimes extending from back to front (though in fact less open than purely traditional Japanese architecture due to the incorporation of Western conceptions of rooms and floor plans). There are actually further intriguing similarities between the Villa Savoye and the Kagoshima Ijinkan interiors, which we will discuss later.

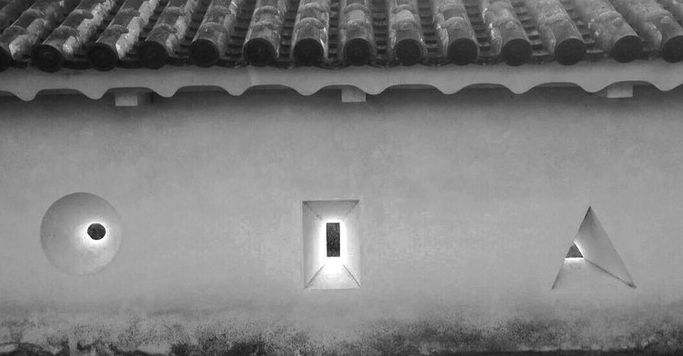

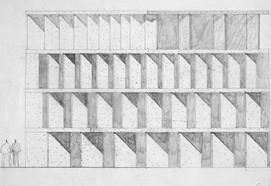

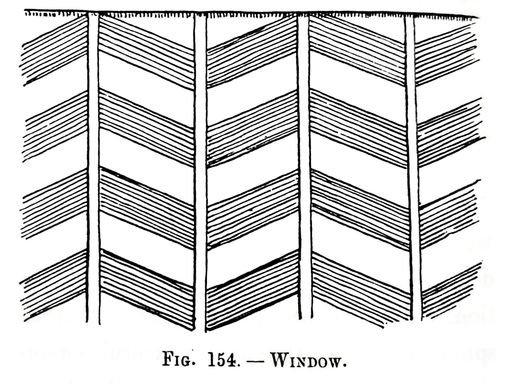

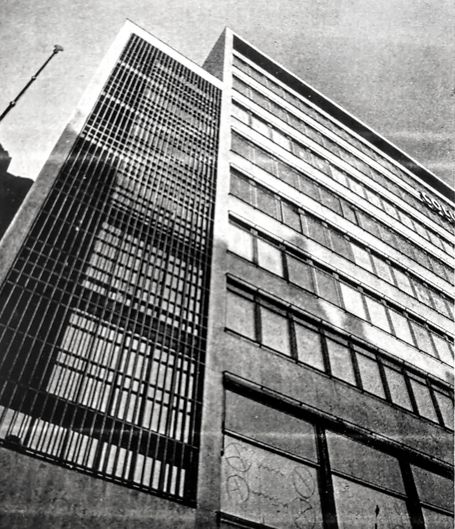

Window Distribution in Vertically Oriented, Multistorey Structures

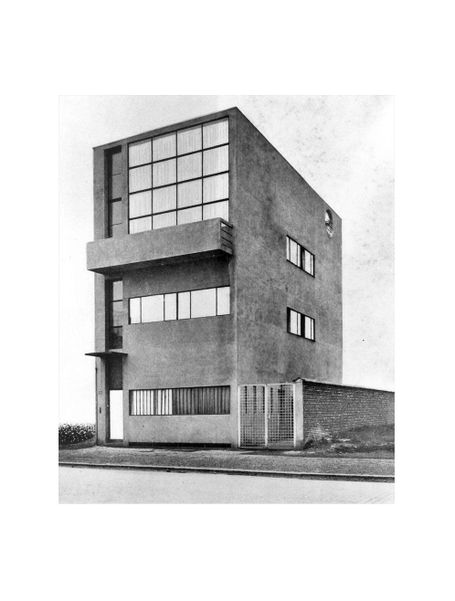

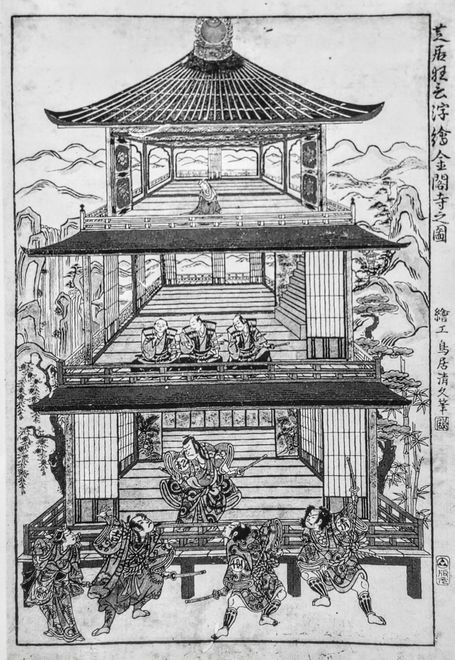

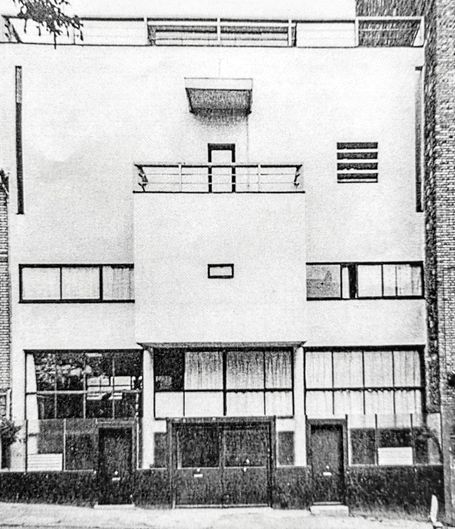

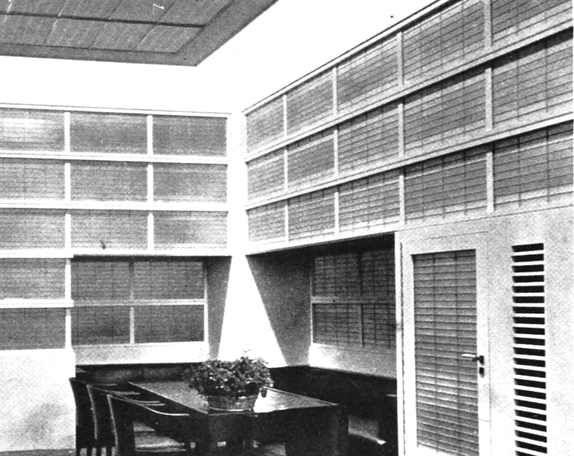

Left: Tomatsu House, Nagoya, Japan, 1901. Center: Maison Guiette, Antwerp, Belgium, 1926. Right: Torii Kiyohisa's 'Shibai Kyogen Ukie Kinkakuji no Zu'(between 1751-1772). The mid and top floor of the Tomatsu house shows windows that extend for most of the length of the wall as in Maison Guiette. And as in Le Corbusier's design, there are smaller and shorter extended windows on the side. As is standard in Japanese homes, Le Corbusier has placed closely spaced grilled (senbonkoshi style) windows on the ground floor. Putting roofing differences and structural peculiarities aside, the basic pattern shown in Le Corbusier's multistorey residential design, of maximally large windows facing front on the second and third levels, grilled windows on the first (ground) level, among other features, follow the pattern of multistorey housing in late 19th century Japan. For further reference, Torii Kiyohisa's print has been added because it also illustrates similar ideas of multistorey design. Other projects of Le Corbusier's, in particular his Maison-atelier du peintre Amédée Ozenfant (Paris, France, 1922), but also his Villa Shodhan (Ahmedabad, India, 1951), or his unrealized projects such as Maison Cumenge (Bordeaux, France, 1926) and Maison Canneel (Brussels, Belgium, 1929), contain analgous conceptions.

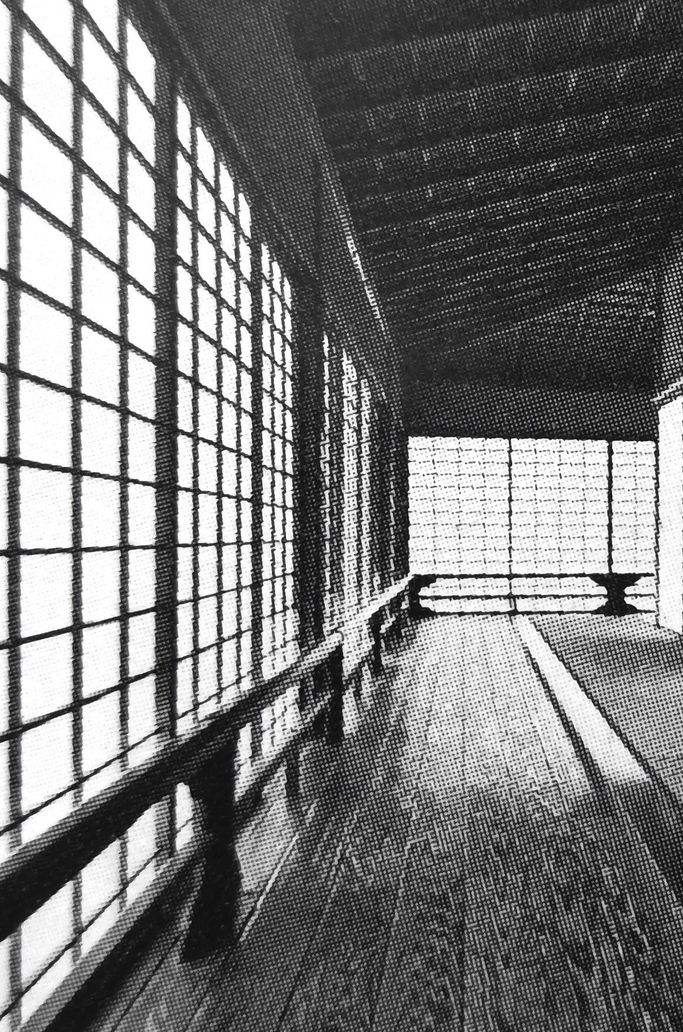

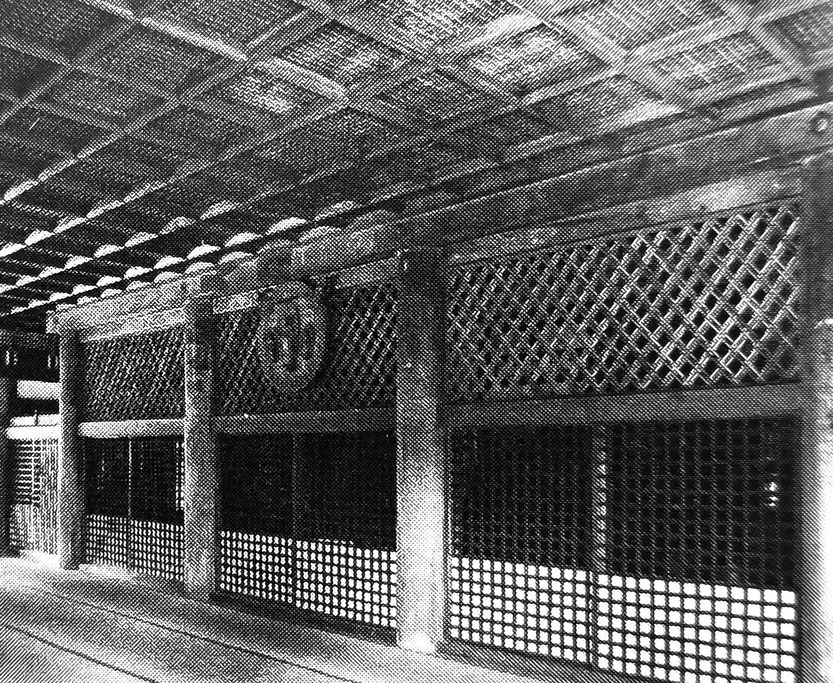

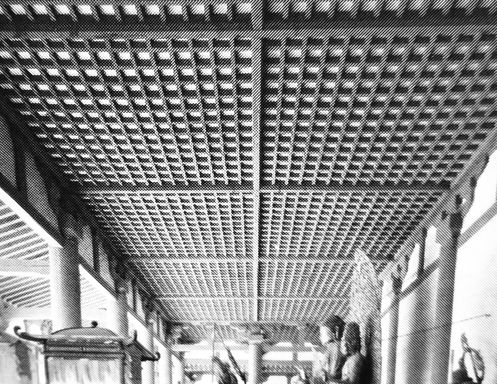

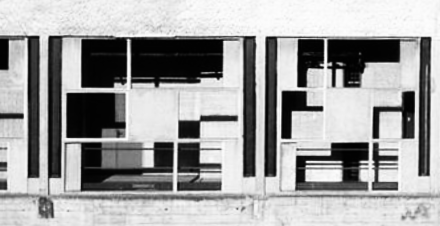

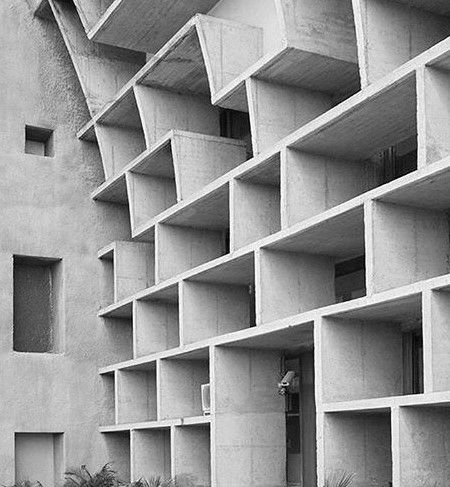

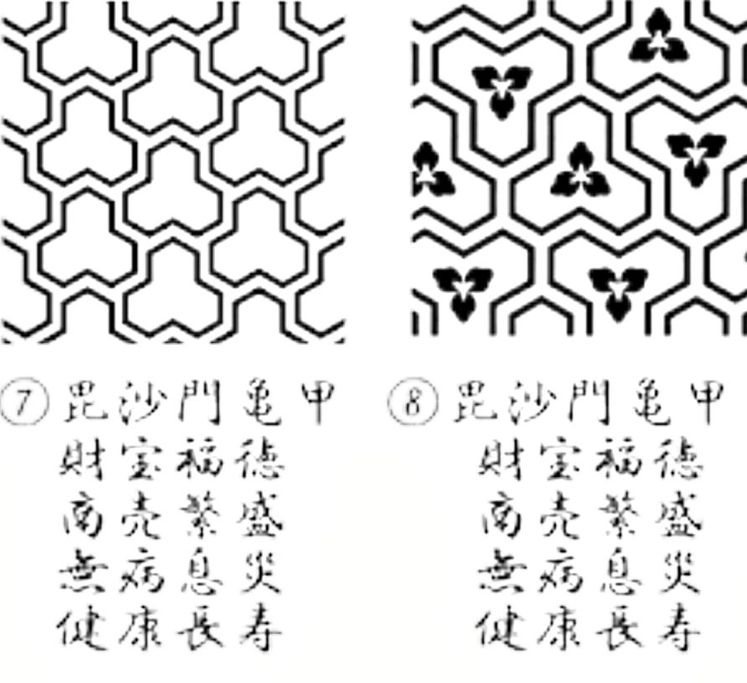

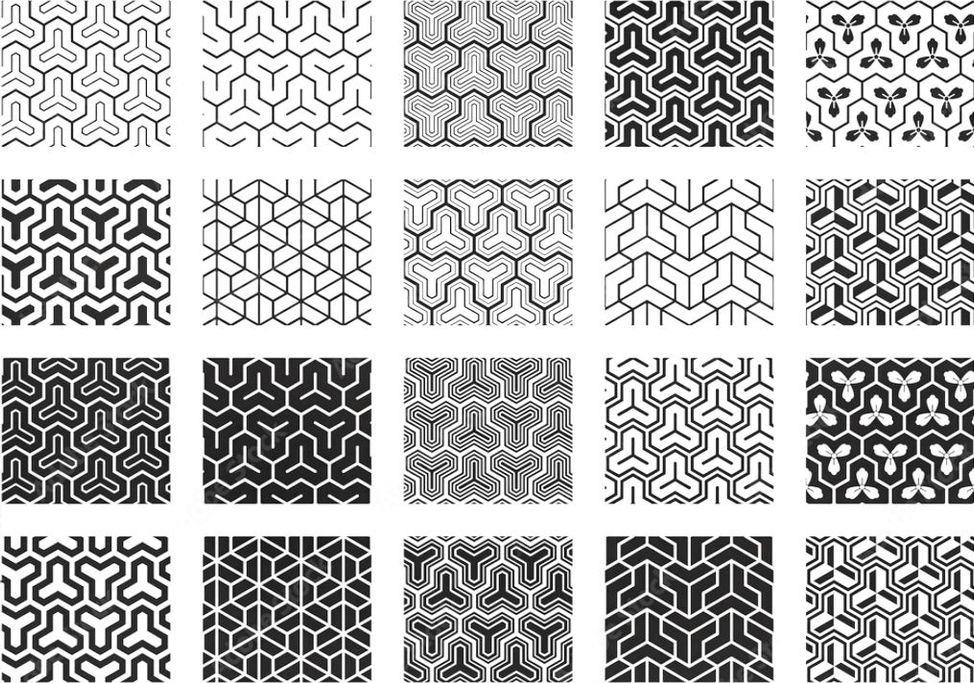

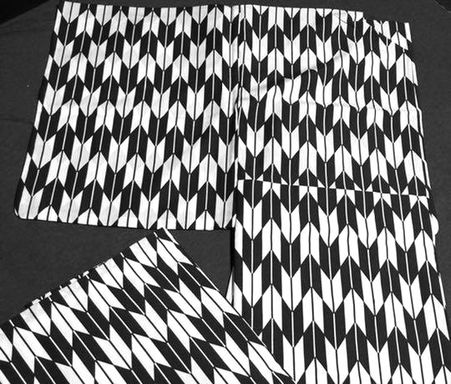

Exterior and Interior Surface Design: Japanese Geometries and Sectionalizations

One of the most visually striking contrasts between traditional Western architecture and Japanese architecture is that of exterior and interior surface appearance, of A) wall surface dominating facades versus window space dominating facades, and of B) interior spaces being divided by thick walls versus movable and often light passing partitions. The latter characteristics are most pronounced in Japan not only in comparison with the West, but with even so with continental East Asia, where stone and brick were more often used to similar effect as in the Occident. The Japanese facade was distinctive in its extensive use of repetitive squares, rectangles, and vertical lines in various proportions over the greater part of facades and interiors.

Those characteristics are, to be more precise, as can be found in Le Corbusier's adoption of them: extensive horizontally extending surfaces of repetitive, primarily rectangular (including square) forms in more often than not similar, but also at times repeating dissimilar, proportions; which are clearly demarcated by relatively thin lines of often similar thickness; these contrasting starkly with wall and window surfaces, creating visually a kind of binary effect; these in turn form upper and lower sectionalizations of exterior and interior surfaces, where sectional divisions arise based on differently spaced or perpendicularly oriented lines (e.g. on one wall surface, a section of narrowly placed vertical lines next to sections of widely spaced vertical lines, or a section of horizontal lines, or squares, or often all of the above); and furthermore, in multiplanar surface combinations (e.g. wall, ceiling and floor; as well as interior and exterior, and layered as in fence, senbonkoshi grill, window, and then shoji sliding door).

Below: Matsuyama daimyo kamiyashiki (main Edo/Tokyo) residence, photographed between late 1871- early 1872. To the right is the scaffolding/screen built before tearing down the structures within; even that seems to exhibit the geometric design aesthetics of Japan.

The Example of the Unités de camping, Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, France, 1956

Below: Left, a preserved 19th century gate house structure at the Edo Tokyo Tatemono-en. Center, Le Corbusier, Unités de camping, Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, France, 1956. Right, typical family room scene that has continued uninterrupted for centuries, 1986.

The dark grid on a white backdrop often appears as a continuous pattern of the ground level as well, in Japan, and on both the exterior and interior, in the scale and proportions as in Le Corbusier's designs. A note regarding color. It is easy to change the impression of architecture with colors, something happening more often over the years with Le Corbusier's buildings. Yet regarding architecture, especially for Le Corbusier, color was secondary, a distraction to the appreciation of space, volume, and form/structure; and is why his works were often in white or unpainted concrete. Therefore in Towards a New Architecture it is 'Mass', 'Surface', 'Plan', and 'Regulating Lines', and nowhere within is color to be found. We could build another Ronchamp and paint it orange or another Savoye with thick zebra stripes; these would succeed in giving a completely different impression and camouflage the architectonic equivalence with the originals. The same might be said about his most Japanese designs: they are often painted in bright 'makeup'.

Below: Ogura Ryuson, View of Yushima, 1880 - 1881. Note in Ryuson's house on the left, the same rectangular window grids combined with sections of wood planks under or next to them with a pronounced emphasis on their horizontality or verticality as in Le Corbusier's Unités de camping exterior, above.

Immeuble Clarté, Geneva, Switzerland, 1930: The fine horizontal 'sudare' and vertical 'senbonkoshi' look of a Kyoto street

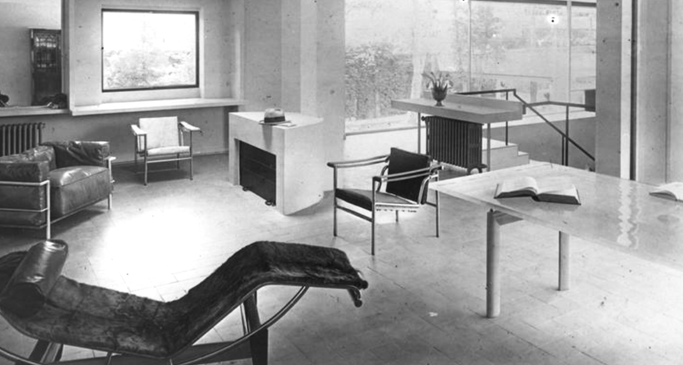

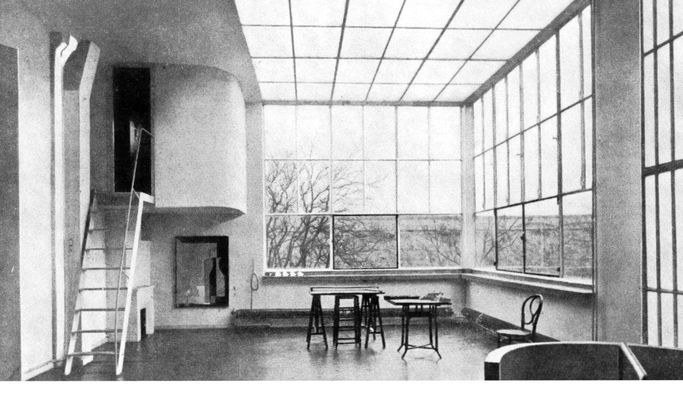

Below: Left Immeuble Clarte window. Right Katsura Imperial Villa, Kyoto. Placed side by side, the two seem to almost blend together. Imagine if we remove the chairs, or if we were to place a row of chairs in the Kyoto villa how we would obtain a similar effect.

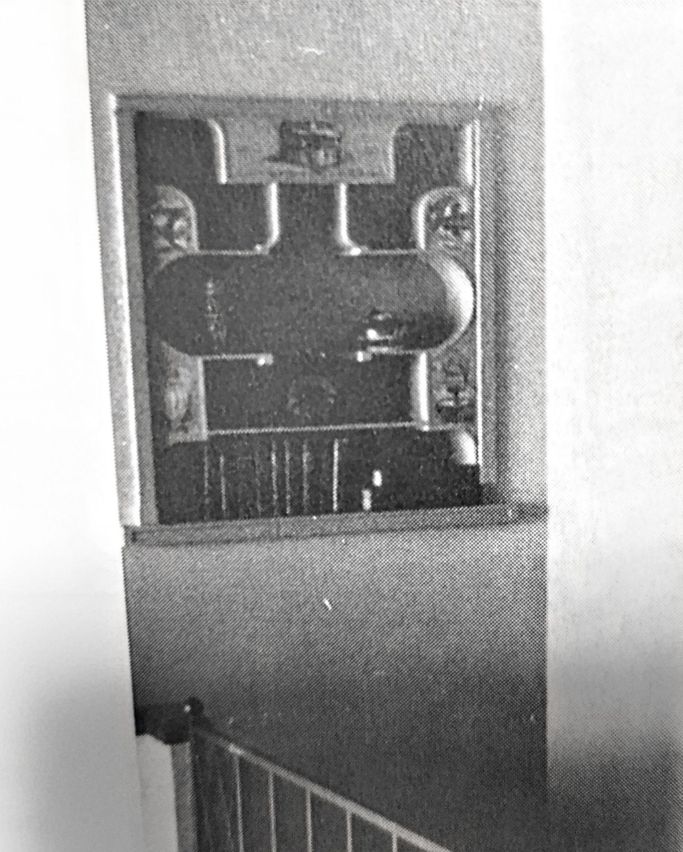

Below: the 'gotenjo' style grided ceiling at Clarté even replicates the details of Buddhist temple ceiling grid pane surfaces, using textured glass instead of wood.

Immeuble Clarté

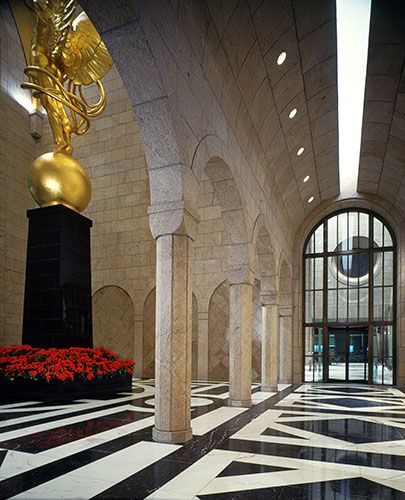

One need only go to Todaiji Temple's Daibutsu-den that houses the Great Buddha, and look up towards the ceiling to dispel all doubts as to whether Le Corbusier was influenced by Buddhist temple architecture in his design of Clarté's stairways and halls, in particular Nara temples, where 'gotenjo' grids rise layer after layer to the ceiling high above.

The Example of the Armée du Salut (Salvation Army), Cité de Refuge, Paris, France, 1929

First photo, Le Corbusier, Armée du Salut (Salvation Army), Cité de Refuge, Paris, France, 1929. Followed by Konchi-in, Nanzenji Temple, Kyoto, early 17th century.

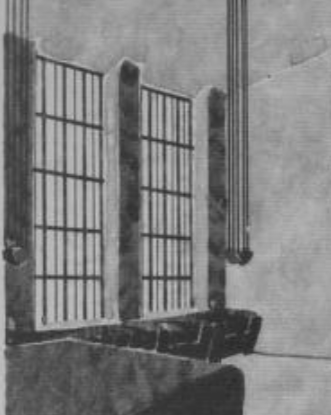

Below: Koshi style framing in the Armée du Salut (Salvation Army), Cité de Refuge, Paris, France, 1929. The grill spacing in the upper left of the photo is slightly wider than that found in Japan, but various types of spacing 'kankaku' can be found according to the thickness and depth of the grill boards. The proportions of the grid to the right can be frequently spotted in Japan.

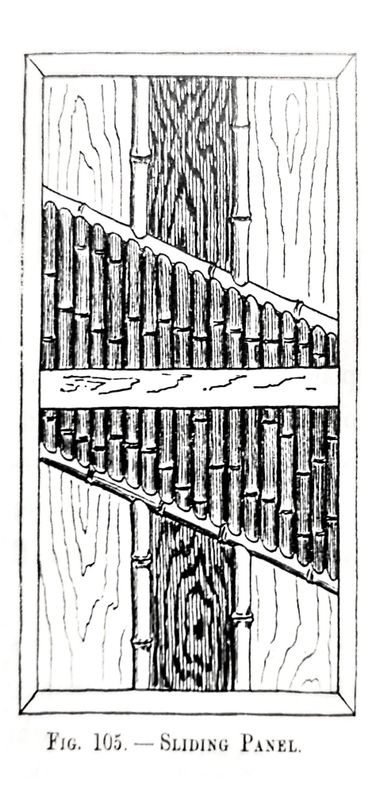

Comparisons with Japanese architecture below. In the Japanese houses below, heavy, massive exposed pillars and beams darkened with smoke intersect above, while below, delicate wood ranma and shoji screens creating lines and rectangles of varying design, situated at different heights due to lighting needs and angles, are integrated as one design as in the Cite de Refuge interior shown above.

Petite maison au bord du lac Léman, Corseaux, Switzerland

"There is actually more sense in this method than may seem at first glance. In this tiny house of 650 ft.² there is a window 33ft. long and the reception area offers a perspective of 45 ft. Movable partitions and disappearing beds permit the improvisation of guest accommodations." (From Le Corbusier's Complete Works, volume 1, 1910-1929) So writes Le Corbusier of this compact house which in various ways, such as movable partitions and disappearing beds reflect features of Japanese homes with their sliding shoji partitions and stored away futon-beds. Even the appearance of the partitions, as shown below, look identical to Japanese byobu of simple homes in Japan, except of course, the addition of metal locks visible on the side. However, on second thought, since the Meiji period, similar modifications of Japanese furnishings and 'tategu' were occurring in Japan in like fashion. Thus Le Corbusier's modernized Japanese elements cannot be said to be necessarily new. Indeed, the entire conception of the house, a simple, affordable, long, one storey structure is reminiscent of low income 'nagaya' (literally 'long house') homes -- though enlarged and 'airlifted' to a marvelous resort setting. The nagaya house of Japan, each built along the same lines, was the closest thing to quickly and mass-produced housing in the Edo period.

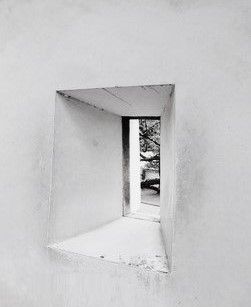

The use of Japanese Style Asymmetry, as seen in Chashitsu (tea house) Window Placements

Besides his five points, his modulor concept, and his preference for raising buildings on stilts, another key characteristic of Le Corbusier's work is his constant use of asymmetry. That use of asymmetry extends to many facets of his work, in his plans and elevations, as it does in Japanese architecture. Japanese asymmetry was early on regarded as one of the defining features of Japanese art and architecture, and perhaps no other culture has practiced it so long and artfully as Japan. That asymmetry is one that often occurs in multiple geometric planes which jut out and intersect with each other. The Hasso-an tea house (below center) is a good example of this.

Maisons Jaoul, Neuilly-sur-Seine, France, 1951 juxtaposed with famous Japanese chashitsu windows.

Below: Windows of Couvent Sainte-Marie de la Tourette, Eveux-sur-l'Arbresle, France, 1953, between Japanese chashitsu (tea house) windows.

The Chashitsu as Model and Microcosm for Le Corbusier

Cabanon de Le Corbusier (Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, France, 1951) compared with Japanese tea houses.

While the design and architectonics take from those of a chashitsu, the philosophical conceptualization of absolute economy reminds one also of Kamo no Chomei's classic Hojoki, written in 1212 (in English translated as: The Ten Foot Square Hut, in French: La Cabane de dix pieds carrés) which ranks among the most renown literary works of Japan.

Note on the Hojoki in Western languages: Translations began to appear from the late 19th century, starting with Natsume Soseki's version (1891) and one based upon it by his professor at Tokyo University, James M. Dixon (1893). Itchikawa Daiji's Eine kleine Huette, Lebensanschauung von Kamo no Chōmei came out in 1902 (Berlin: C. A. Schwetschke und Sohn); A. L. Sadler's The Ten Foot Square Hut and Tales of the Heike in 1928 (Sydney: Angus and Robertson Ltd), was the standard for decades in English. Other translations, to name a few more, include those by Minakata and F. Victor Dickins (1907) and Alexander Chanoch (1930); even an Esperanto version was done by Nohara Kyuichi (1936).

Here is are a few passages from Chomei on his cottage (Sadler's translation):

"If I compare it to the cottage of my middle years it is not a hundreth of the size. Thus as old age draws on my hut has grown smaller and smaller. It is a cottage of quite a particular kind, for it is only ten feet square and less than seven feet high... All the joints are hinged with metal so that if the situation no longer pleases me I can take it down and transport it elsewhere. And this can be done with very little labor, for the whole will only fill two cart-loads, and beyond the small wage of the carters nothing else is needed.

... In the eastern wall there is a window before which stands my writing-table. A fire-box beside my pillow in which I can make a fire of broken brushwood completes the furniture. To the north of my little hut I have made a tiny garden surrounded by a thin low brushwood fence so that I can grow various kinds of medicinal herbs. Such is the style of my unsubstantial cottage.

As to my surroundings, on the south there is a little basin that I have made of piled-up rocks to receive the water that runs down from a bamboo spout above it, and as the forest trees reach close up to the eaves it is easy enough to get fuel. ...

In the morning, as I look out at the boats on the Uji River by Okanoya I may steal a phrase from the monk Mansei and compare this fleeting life to the white foam in their wake, and association may lead me to try a few verses myself in his style. Or in the evening, as I listen to the rustling of the maples in the wind the opening lines of the "Lute Maiden " by the great Chinese poet Po-chui-naturally coccur to my mind, and my hand strays to the instrument and I play perhaps a piece or two by Minamoto Tsunenobu. ..."

For those who know the location, views, and ideas associated with Le Corbusier's cabin, the above might ring a few bells...

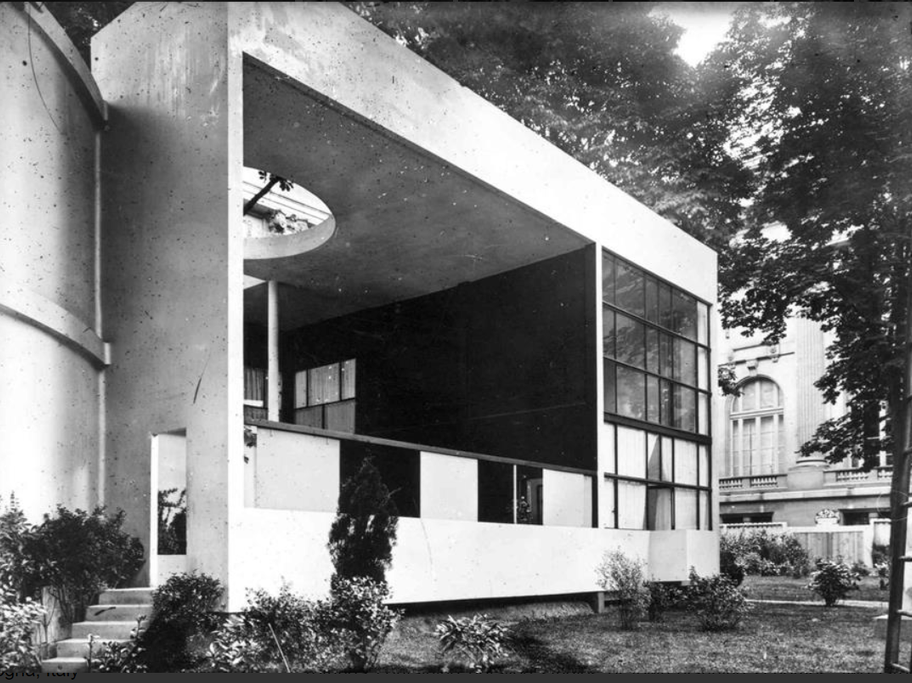

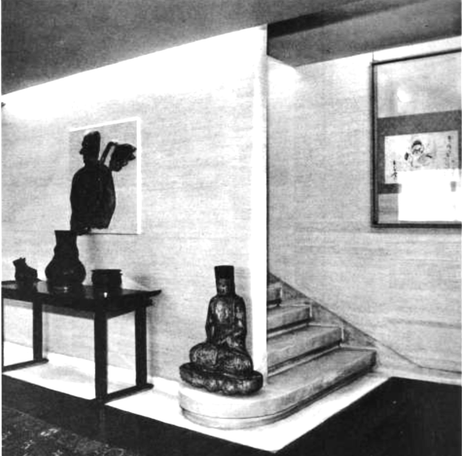

Indeterminacy, Integration, and Interpenetration of Exterior / Interior Space

Below: Left, Pavillon de l'Esprit Nouveau, Paris, France, 1924. Right, Shokatei chashitsu of Katsura Villa, Kyoto, early to mid-17th century. Note how in both pavilions how one climbs steps obliquely to the structure, which leads to a space that is half indoors and half outdoors, where the boundaries between the two are hard to define--but would not most judge the Shokatei does it more artfully?

Below: Maison Citrohan, unrealized project sketch (1922) compared with a model of the Taian chashitsu (before 1592) to the left; and to the right, a typical traditional house front in Takaoka City, Toyama (19th century). Large eaves or awnings on one side of the tea house, supported by two poles, under which grilled windows and sliding doors open to the exterior as in Le Corbusier's sketch. Round windows to one side were also a common feature not only of tea houses, but of city houses in Japan. Offset entrances to one side in Le Corbusier's sketch, creating asymmetries, as in both the tea house and city house shown here, are a defining feature of Japanese secular architecture.

Below left: Le Corbusier House, Maisons de la Weissenhof-Siedlung, Stuttgart, Germany, 1927; right Miidera, Kojo-in, Kyakuden (guesthouse), Shiga,1601

Another example of Le Corbusier's use of Japanese type approaches to the integration/interpenetration of interior and exterior space, of nature and the man-made. In Japan, structures which are fundamentally long corridors encased by extremely porous walls, or otherwise are open to the exterior supported only by pillars (or some combination of the two) have an ancient history. One of the most famous of these types of structures is the Kojo-in guesthouse, 'Kyakuden' of Miidera, renown for its wall which extends unitarily out into space. An almost 'Escher' type of visual effect is achieved confounding distinctions of interior and exterior.

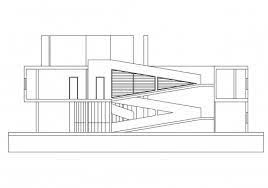

Views of the outstanding feature of the Le Corbusier's design, i.e., the peculiar 'コ' shaped (konojigata) structure below and one of the analogous elongated spaces of the Kyakuden.

Below: Early color sketches by Le Corbusier (center) show closer resemblance in conception to the Miidera Kyakuden. The emphasis on garden-building integration and interpenetration is more evident and central as a basic idea, where the line between inside and outside is indeterminate and can be modified. Like the Kyakuden, the wall can be closed or opened in various degrees. If one looks carefully, in Le Corbusier's sketch there a pond adjacent to the building, which seems to flow into the structure, much like the effect of the pond of the Kyakuden, which seems to almost run underneath the building.

While the important point is the peculiar quality of indeterminate, interpenetrating indoor and outdoor space, it is in the various corresponding smaller, idiosyncratic details that are telltale clues that Le Corbusier was in fact conscious of the Kyakuden, as those shown below. Note the similar full height exterior exposed partitions under the roofs, and the smaller partitions hanging out beyond.

Le Corbusier's House was just one of many houses at the development at Stuttgart. Here we have only looked at one, but that the general project itself was one which was conceived with Japanese architectural principles in mind can be surmised from the extract below by Le Corbusier himself regarding the basic concept of the house interiors:

"The large living room was created by the removal of mobile partitions which were used only at night to convert the house in a way similar to a sleeping-car. During the day the house was open from one end to the other, forming one large room." (Oeuvre complète, volume 1, 1910-1929, www.fondationlecorbusier.fr) Furthermore, the beds, it seems, could be stored away in hidden compartments, like bedding in Japan.

Now for anyone who knows traditional Japan, all of the above certainly sounds like a perfect description of a Japanese interior!

The Confirmation of Eclecticism in Le Corbusier's Work

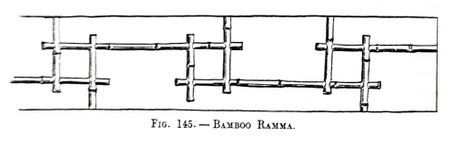

The example below provides a clear case of eclecticism in Le Corbusier, despite his determined blending and abstraction of borrowed motifs. The bamboo theme, the staggering of narrow vertical pane sizes, an early element of japonaiserie interiors, can be found in the Couvent Sainte-Marie de la Tourette (Eveux-sur-l'Arbresle, France, 1953).

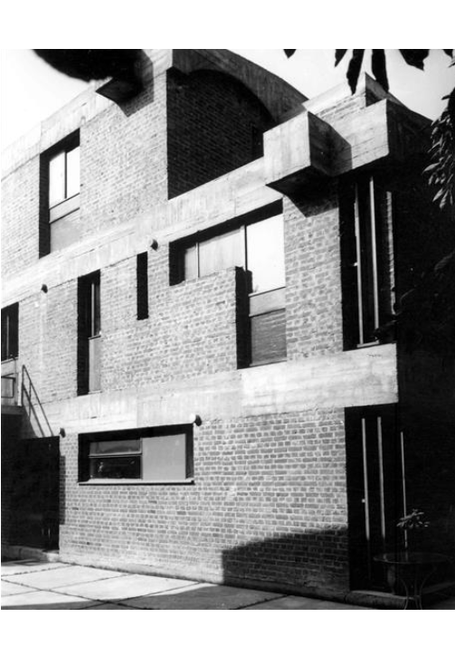

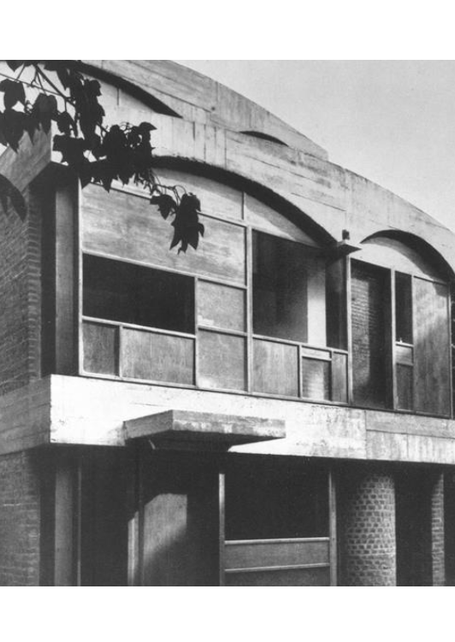

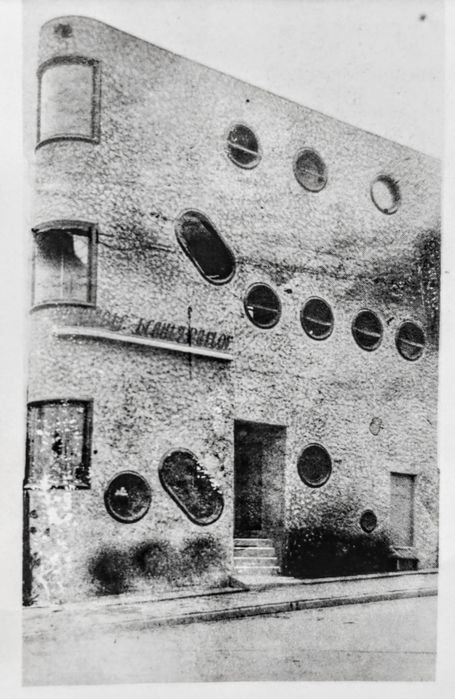

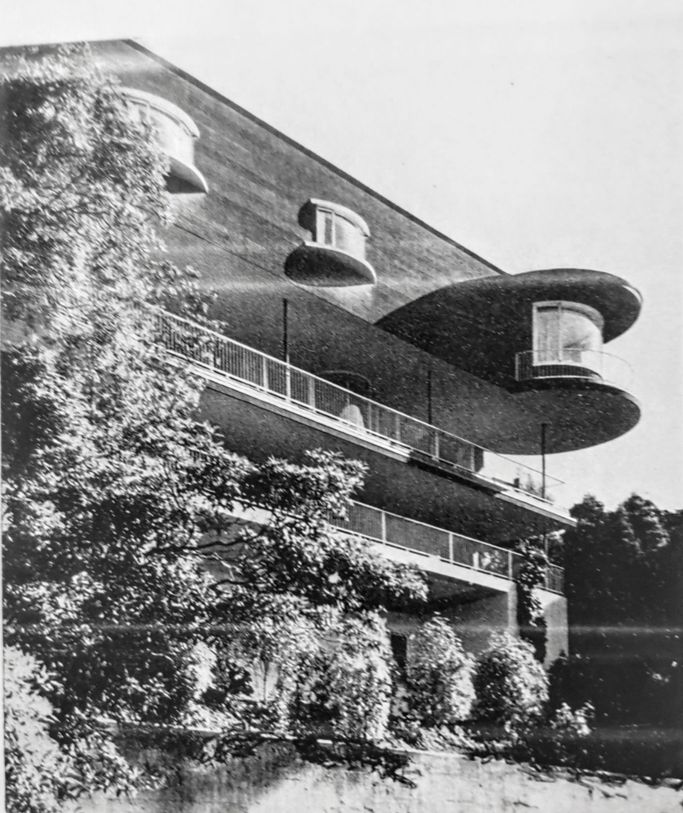

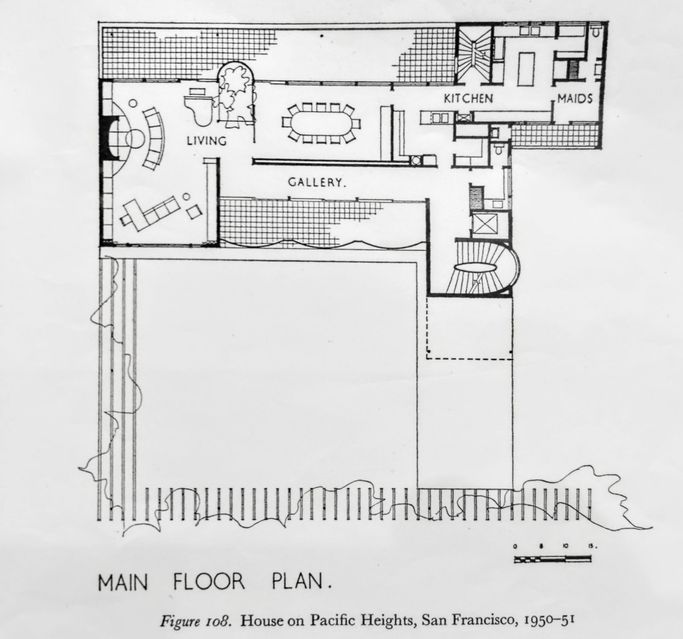

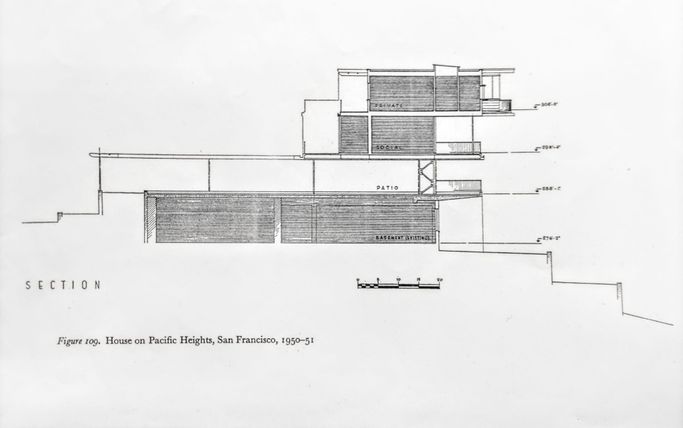

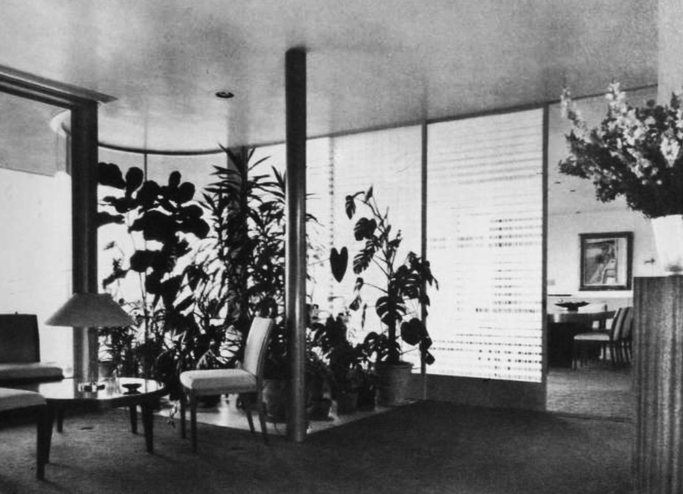

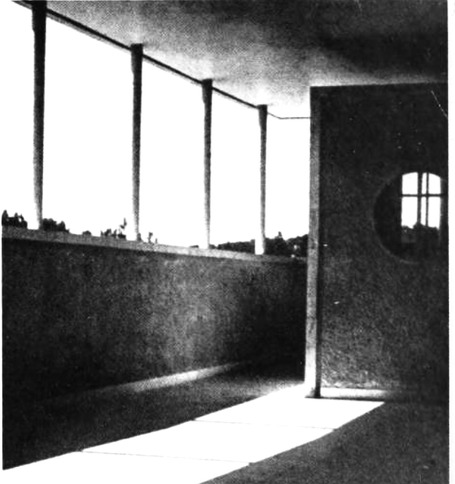

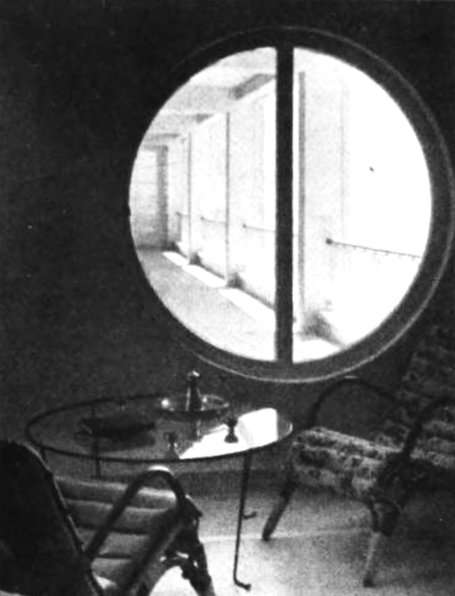

The Round (and oval) Windows of Villa Schwob, La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, 1916

It is not only in the rectangular windows and grids, or the vertical and horizontal use of grills that a Japanese influence can be detected in Le Corbusier's exterior and interior facade designs. The use of Japanese style round windows, with fine gridwork, in various different planes for both the exterior and interior, along with other more typical oriental flourishes such as garden pavilions with curving roofs (Villa Jeanneret-Perret, La Chaux-de-Fonds, Suisse, 1912), can found in in his early works, which are still relatively traditional in their plans and conception of rooms.

A good example is Villa Schwob, is one of the few designs that the Fondation Le Corbusier admits to an oriental influence in its summary for the work:

"This is the best-know and most remarkable of Charles-Edouard Jeanneret's creations in La Chaux-de-Fonds. Rich in symbols, and with elaborate technical and aesthetic aspects, it is his most accomplished work before leaving for Paris. The ochre brick-work associated with concrete accentuates the oriental character of the house."

Thus it is not only the windows where an oriental influence may be found, but here we will focus on his combined use of round and rectangular windows and grids, especially inside the house. Round windows were often filled with fine grids in Japan, either made of woven bamboo or twigs, or with shoji (with finely spaced kumiko) sliding partitions that could be slid open. Round windows have long been a traditional element of both secular, residential architecture and sacred, Buddhist retreats for meditation in Japan. In the former they were often placed on second floors, off to one side or facing different angles and generally smaller in size than those in temples or chashitsu for tea ceremonies where they were often situated prominently in a single floor structure.

There is no mistaking the oriental flavor of Le Corbusier's round windows on the second floor overlooking the living area. Originally the surrounding walls were painted black, and they give the appearance of lacquered surfaces. The round or otherwise oval windows are placed abundantly at various angles as in the Japanese examples shown below, and in combination with both expansive and small grided window or vent sections, also reminiscent of Japan.

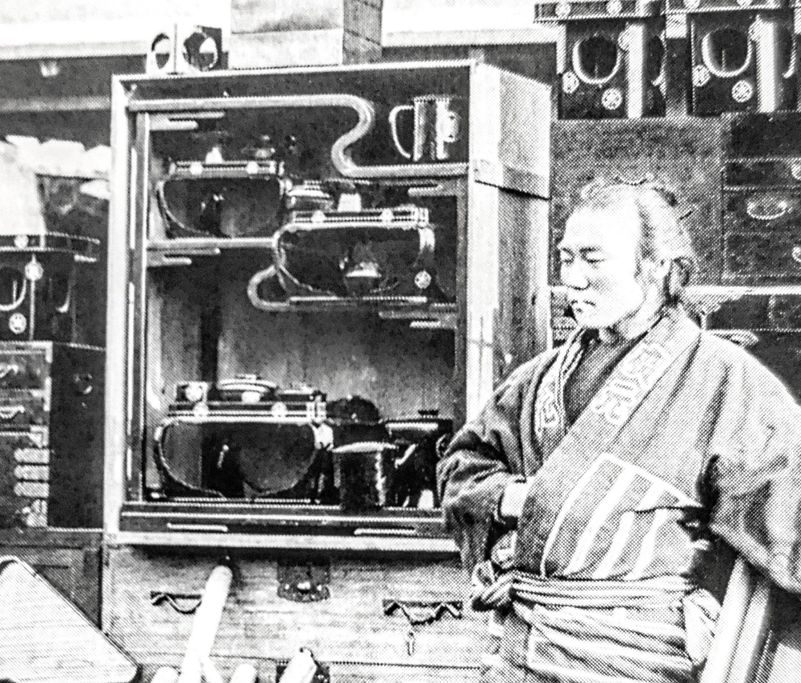

There are various other interior details of Villa Schwob that are very much in an oriental style. Below a vendor with a Japanese cabinet with curved chigaidana shelves filled with goods (left) next to Le Corbusier's built-in cabinet with curved chigaidana shelves (right), and though indistinct, a Japanese or Chinese figurine and incense burner are placed on the shelves. The reader, if he/she is knowledgeable regarding Japanese and Chinese antiques, has probably come across cabinets with more exactly the same configuration of Le Corbusier's shelves.

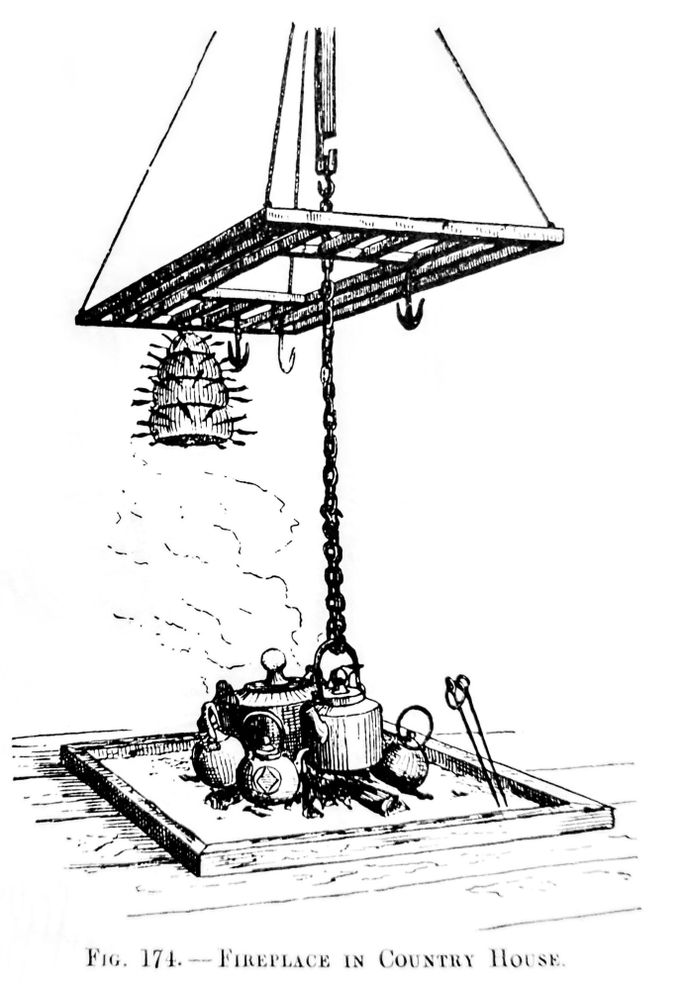

Below: Le Corbusier's Villa Schwob living room chandelier( right), is almost identical in design to wooden Japanese farmhouse irori fireplace wooden hanging grids. To the left is a illustration from Edward S. Morse's Japanese Homes and Their Surroundings (1886), which has a large central opening for the kettle holder to pass through, but often these farmhouse grids are more exactly like that of Le Corbusier's chandelier, that is 7x7 squares, the kettle chain passing through the middle square. Le Corbusier has placed bulbs hanging from his chandelier, but even in Japan, with the coming of electrification in the early 20th century, old photos show single light bulbs hanging from these irori fireplace devices.

As is often the case with Le Corbusier's designs, his early sketches are often more oriental in feeling than his completed buildings perhaps reflecting the constraints of culture, client wishes, and at times, means. Below, the 'yashiki'-like quality of the compound, with Japanese style lamps in the garden near the entrance as found in shrines, and surrounded by a wall with 'yagura' reminiscent gate posts with curved roofs, and round windows, convey an unmistakable oriental impression.

Below: left followed by right side perimeter wall details. Note small details of the 'ikegaki' style fencing in the left image, and the yagura-like entrance gate and lamp within the compound, in the image to the right.

Maison de week-end Jaoul, project, 1937

An example of where Le Corbusier's use of round windows has more clearly Asian connotations is his project for a small week-end house raised on stilts. The facade, when seen in color, in browns and yellows, looks very much like the patchwork of bamboo wall framing, reed and wood wall materials that are reminiscent of Japan, but perhaps even more so of Southeast Asia. Anyone who has spent time in the countryside of Cambodia, for instance, should recognize the analogous nature of Le Corbusier's concept here. His project Maisons rurales (Lagny, France, 1950), is even more so Cambodian in form; but of course minus the roof. On second thought, it was not as if corrugated tin roofs did not exist in Cambodia, thus a more exactly similar design might be found there. By 1950, designs like this could not in anyway be considered original as modern architecture; especially in Japan where traditional facades were being tinkered with in a variety of ways. Even the idea of an inverted roof, the V-shaped roof, shown further below, was not new; for example, Endo Arata's Ginza Hotel utilized the same idea more than a decade earlier than the Jaoul sketch of late 1937.

The Confirmation of Precedents in Le Corbusier's Work

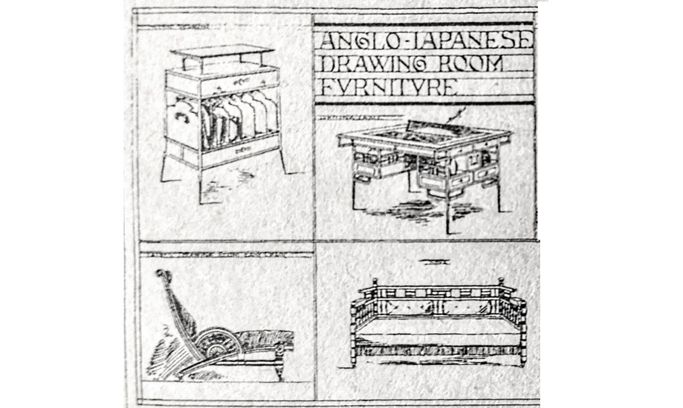

Regardless of whether it be conscious borrowing or not, the recognition of precedents is an important part of any appraisal of the historical value and significance of architectural design. As Le Corbusier has often been acclaimed for outstanding originality and innovation, it is important to establish the simple fact of frequent precedents in his work. Villa Church (Ville-d'Avray, France, 1927), with a typical Le Corbusier Interior, shows suspended, built-in wall to wall cabinetry with horizontally long sliding doors as in Japanese traditional built-in cabinets with ceiling 'tenbukoro' and floor 'jibukoro'. Low seating with minimum height backrests follow the 19th century 'Anglo-Japanese Drawing Room Furniture' of Edward William Godwin and testify to the fact that the fundamental conception of Le Corbusier's interior furnishings had precedents in older, Japan inspired European interior designs. In Japan, the entire center of gravity was lower, where seating was on zabuton cushions, or on the floor, or on backless benches, or foldable, portable seating without backrests, and of course tables were made to be used at these heights, and this influenced ideas of interior design already in the late 19th century. Indeed, the concept of the low 'coffee table' may very well originate from the use of Japanese 'zataku' in Western homes. Also, by the early 20th century, zabuton floor cushions with attached backrests, and furnishings to fit in Japanese scale rooms appeared in Japanese inns and hotels bringing Japanese furnishings one step closer to modern designs.

One of the instrumental personalities in shaping Le Corbusier's interiors was Charlotte Perriand, whose use of Japanese architecture and crafts is well documented in Charlotte Perriand et Le Japon (2011), an exhibition catalogue that is much more than that and a must read for anyone wishing to further probe the strange contrast between Le Corbusier's noticeable disinterest in Japanese architecture displayed to fellow Europeans (including Antonin Raymond, a well-known architect in Japan), and the enthusiasm for it by someone closely associated with him. Though abundant material in the form of books, ukiyoe prints, and photographs of Japanese architecture would have been available to Le Corbusier from his early days, he also had ample opportunity, not only through Perriand, and certainly after 1928 and through most of the 1930's, to discreetly learn about Japanese architecture from some of Japan's most promising young architects working at his office (not to mention those visiting) including Maekawa Kunio and Sakakura Junzo; and after WWII, Yoshizaka Takamasa.

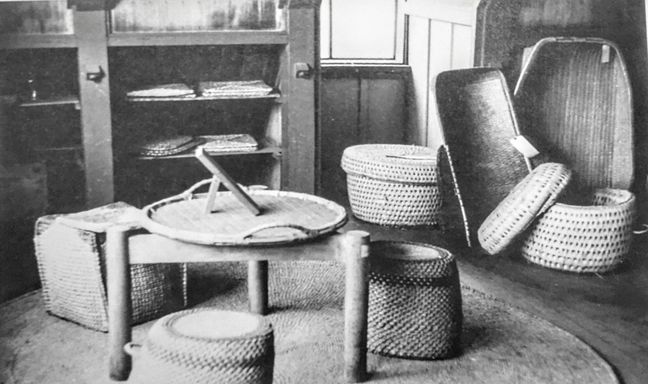

Below from left to right: A scene from the Nenjugyoji Emaki (picture scroll of festivities throughout the year) of the 12th century, showing low drum-like stools surrounding a low dining table; followed by some examples of furniture designs by Charlotte Perriand.

The second image ,showing Perriand's table (1937, photo 1940), is clearly based on a Japanese winnowing device; the chairs are basketwork of the villagers in Yamagata.

The third image is that of a dining room set designed by Perriand, exhibited at the Maison Japonaise, Salon de Arts Menagers in Paris, 1957. The chairs look very much like Japanese hand-held noh drums.

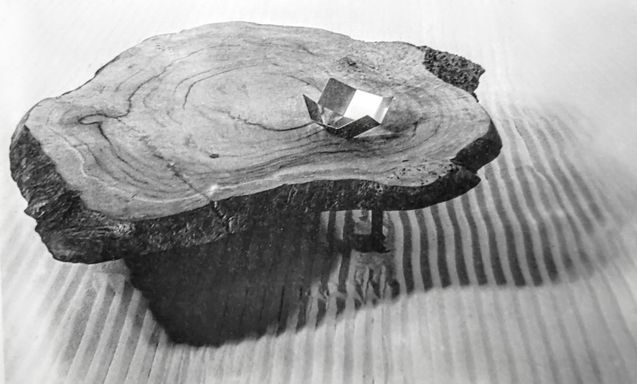

The last image is that of a table designed by Perriand (1941), indistinguishable from Japanese zataku tables made from cut tree trunks, except that the legs are metal rather than wood. The asymmetrically rounded forms of the modern dining table in the previous image is an abstraction of such traditional, organic table forms.

The clear evolution of modern interior design, in the case of Perriand, from traditional Japanese interiors or non-furnishing related folk crafts (re-employed to serve as furniture), is clearly documented in Charlotte Perriand et le Japon (2011, photos below from the same).

Interlocking and Interpenetrating Planes, Lines, and Spaces

Built-in combinations of cabinet and 'floating' shelf formations

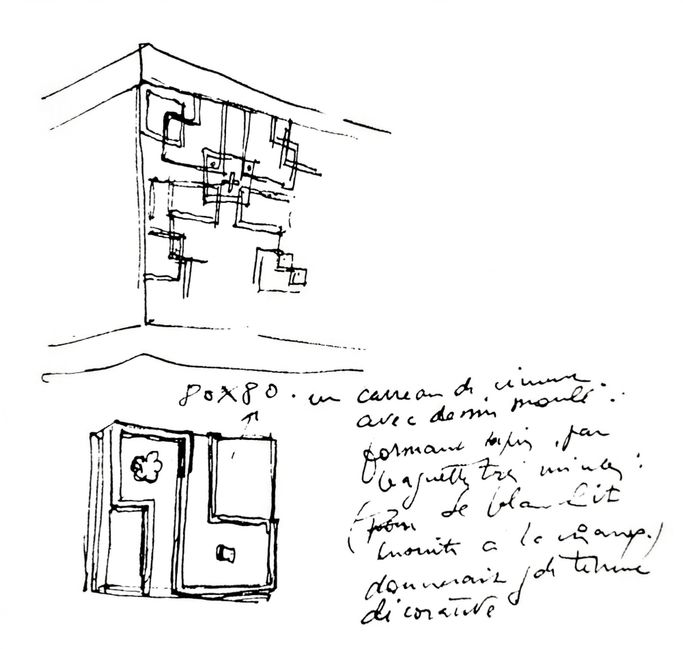

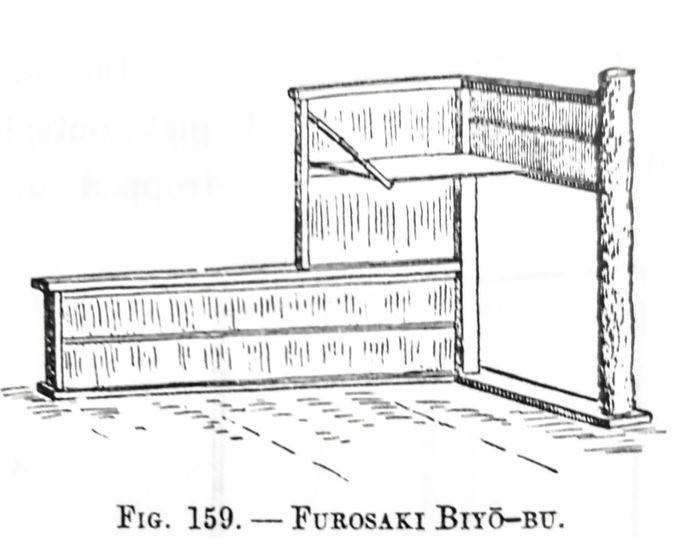

We should note here that 'chigai-dana', especially the more complicated versions as the 'Kasumi-dana' of the Shugakuin Villa of Kyoto, contained a working conceptualization of complex form/space interpenetration and structural support; of how walls, floors, ceilings, rooms, might converge and diverge, interlock or separate and change in multiplanar ways. In some of Le Corbusier's sketches there seems to be a chigaidana like approach to trying to derive solutions for a project. Illustrations of chigaidana can be found in various 19th century European and America texts, such as Edward S. Morse's 1886 Japanese Homes and Their Surroundings.

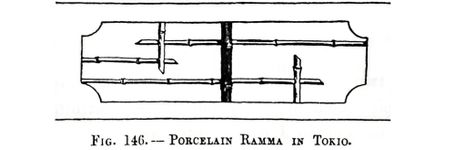

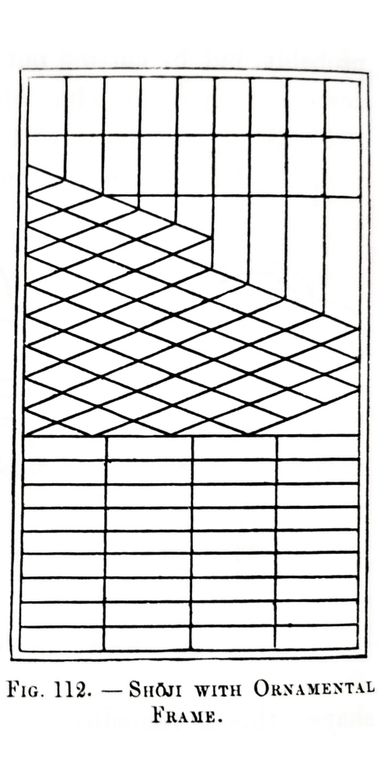

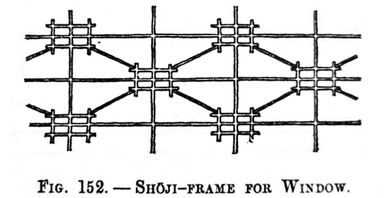

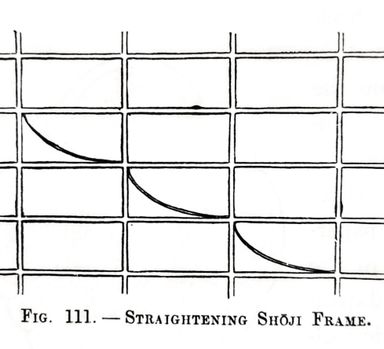

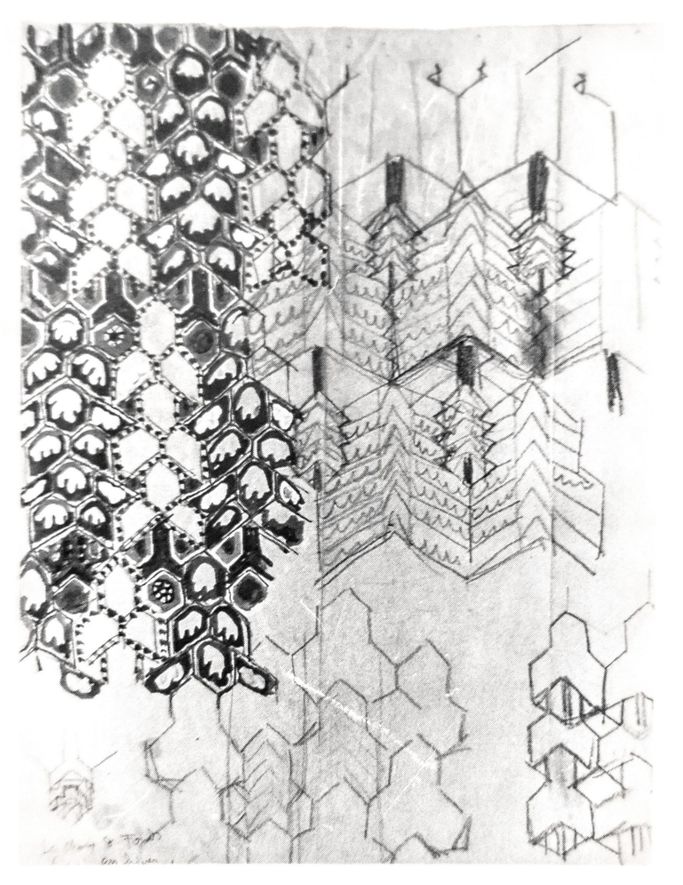

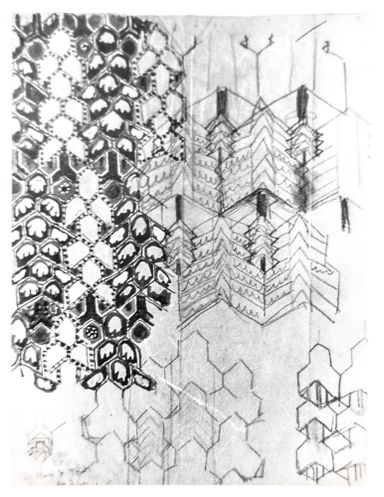

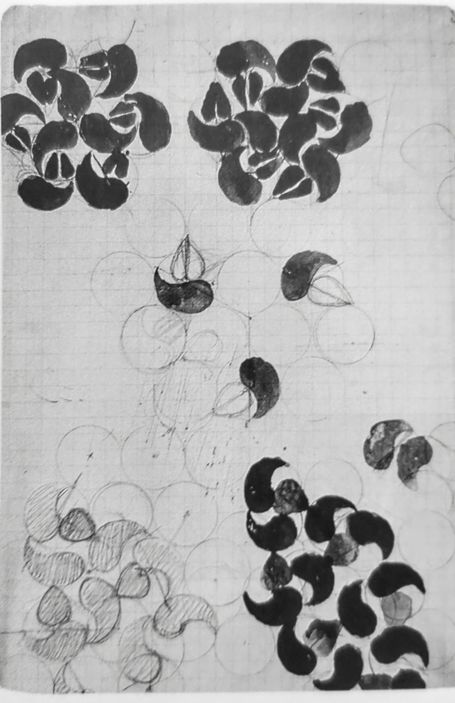

Early sketches by Le Corbusier of decorative elements also reveal Japanese conceptions of interlocking patterns, as shown below. Again, one can find points of commonality between Le Corbusier's designs and the illustrations in Morse's Japanese Homes and Their Surroundings (1886) and Christopher Dresser's Japan: Its Architecture, Art, and Art Manufactures (1882). Similar Japanese patterns would later be described in Arthur Dow's (Ernest Fenollosa's one time assistant at the Boston Museum) Japanese design based Composition (1899), which Frank Lloyd Wright seems to have studied (see Smithsonian Magazine, 'Frank Lloyd Wright Credited Japan for His all American Aesthetic' June 8, 2017) and used as a source for architectural ideas.

Intersecting, colliding and overlapping geometries and planes as illustrated in Edward S. Morse's Japanese Homes and Their Surroundings (1886) as a possible source of inspiration for modernist plans and elevations. Rather than focusing on one to one correspondences, the following examples show how even one book available in Le Corbusier's time, contained numerous images which hint at and lead to some of the basic aesthetic principles and concepts in his most famous work, the Villa Savoye.

This is not to insist that Le Corbusier must have used Morse's book; another possibility is Arthur Dow's Compositions, mentioned above. And as J.S. Cluzel in Le japonisme architectural en France, 1550-1930 (2018) amply illustrates, similar images and records of Japanese structures, including many built in Europe, would have been available in Francophone countries, including Le Corbusier's part of Switzerland, not to mention plentiful German sources. It should be stressed that the type of images in Morse were plentiful in Europe by the early 20th century, certainly by 1914, not only in books of Japanese art and architecture, but guidebooks, exposition memorabilia, a variety of journals, abundant ukiyo-e prints, artist sketches by westerners, photographs, Japanese postcards, and even in elaborate stage sets for opera productions such as Madame Butterfly, or small wood models that were brought home by western visitors to Japan. Morse's illustrations however, are an example of how one reference could have acted as a sourcebook for many of his ideas.

First, a sampling of intersecting, colliding, or overlapping geometric formations in Morse's book.

Compare the above designs with the floor plan and sections of the Villa Savoye below.

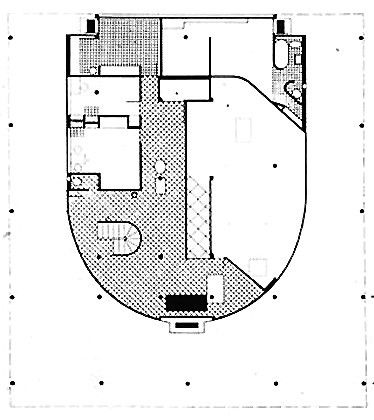

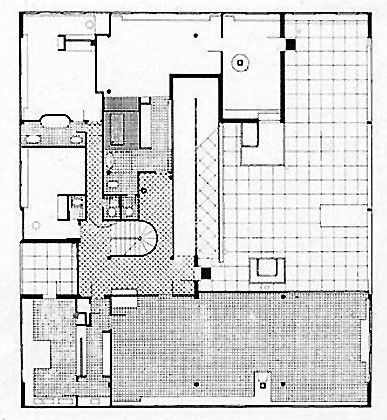

Below: Floor plans that have partially overlapping lines, staggered rooms of varying rectangular shapes and sizes fitted together like a puzzle, U shaped circulation spaces, etc. The plan in the middle is that of the mid level (main residential floor above the ground level) of the Villa Savoye, with illustrations from Morse on both sides.

Below: An idea of pronounced 2nd floor extension over the 1st floor facade, to a degree that surprised Morse. The Japanese construction is in some ways more advanced in its use of cantilevering, and that in wood!

Below: Diagonally angled walls, changes in material, window and door size in 3-D asymmetric positioning at different levels, small projecting single shelves, varied intersecting of planar lines.

Below: The clustering, juxtaposition of different volumes and planes with different geometric qualities, such as round and thick contrasted with the thin and porous, and various curved and straight lines converging from more wider open spaces. The similarities are not literal but conceptual, spatial. In the first Morse illustration there is a clustering of structures around a circulation pathway/entryway, including curved walls, delicate structures, and changes in ceiling and floor height. In the second Morse illustration of a garden, there is a convergence and divergence of forms and function, where thick rounded shapes are placed close to fine rectangular grids, combined with changes of floor/ground levels and line spacing of horizontal and vertical elements, also seen in the first illustration.

Below: Long, walled on one side corridor-like garden paths, set at right angles to each other, creating forced turns, plant clusters or grills hiding or partially hiding areas tucked away beyond.

Examples of short partitions extending from the building structures into the garden, obscuring the view of a small area beyond.

Plantings are clustered, leaving large unplanted central open areas. Walls/fences with apertures are frequently changing direction, creating complexity and interest.

A final observation regarding the Savoye and Morse. Multiple planes that are cut and thus of different height, or projecting, or perforated, but nevertheless all connected as a single architectonic entity.

Comparisons with Officially Registered Historic Structures in Japan

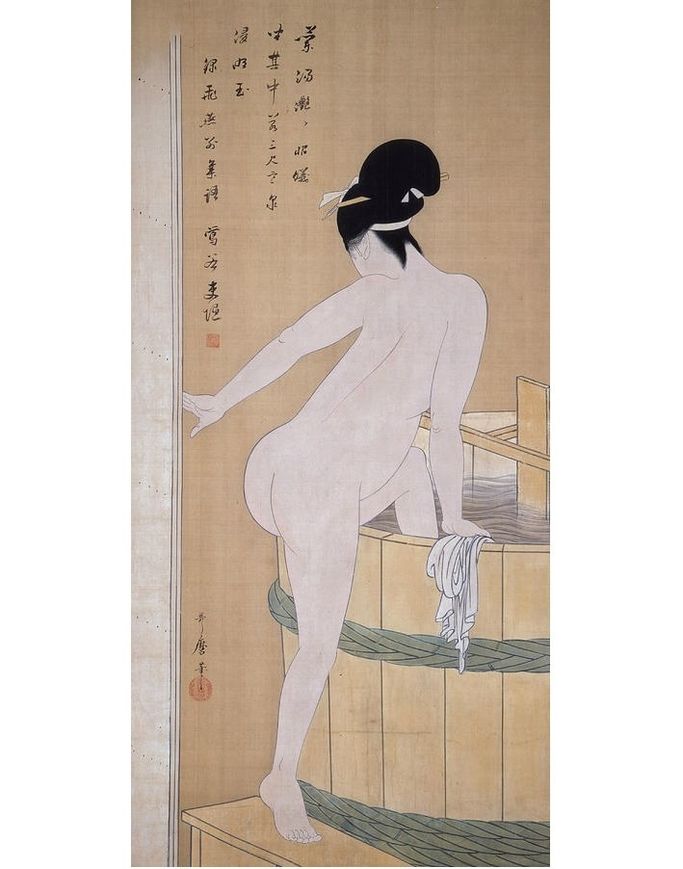

Japanese public and hotel baths and the Villa Savoye bathroom

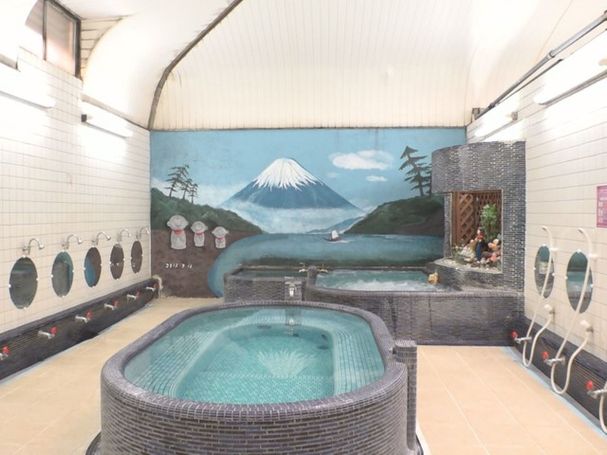

Le Corbusier's bathroom (center) is clearly reminiscent of Japanese baths in hotels, inns, hotsprings, and public baths (sento) across the nation that existed at the time of his designing Villa Savoye. Public baths often were done in light blue with black or grey trim, with scenes of Mount Fuji, or other local scenes of mountains, trees, and lakes. They were low set, and surrounded by open areas with facets for washing oneself before entering the bath. Note how Le Corbusier's bath shares many features with the two examples shown below (left, the Jizoyu in Nagoya, c.1905, moved and rebuilt between 1912-1924; and right, the Waka no Yu in Maizuru, Kyoto, 1903). Even Le Corbusier's irregularly edged low tile wall seems to be a reflection of mountain depictions or hill-like constructions in Meiji, Taisho, and early Showa public and hotel bath interiors.

Opening, curved wall surfaces with grill-work designs

Below: Left Negoroji Temple Great Pagoda, Wakayama. Right Villa Savoye, ground floor.

Low incline and gradient movement, elongated U-shaped pathways between floors

Earlier, we looked at basic structural parallels between the Kagoshima Ijinkan and the Villa Savoye. Another observation should be added. While the Ijinkan still uses steps, each tread is extremely long, with the stairway extending straight and relatively narrow and bending back the same length, with unadorned white walls as in the Villa Savoye, creating a similar relaxed pace and easy feeling of accession without distractions.

Precedents for Aspects of other Le Corbusier Designs

Projecting overhead constructions in grid accentuated open floor plans

Below left, Le Corbusier Maison-atelier du peintre Amédée Ozenfant, Paris, France, 1922. Right: 'doma' area of the Yoshimura residence, Habikino, Osaka, basic design early 17th century, additions until the first years of the 19th century. Note the overhanging cubicle like constructions on the upper left corners of both photos. A ladder is used to reach the small window-like door to the cubicle in the Yoshimura residence, but is not depicted in the photo.

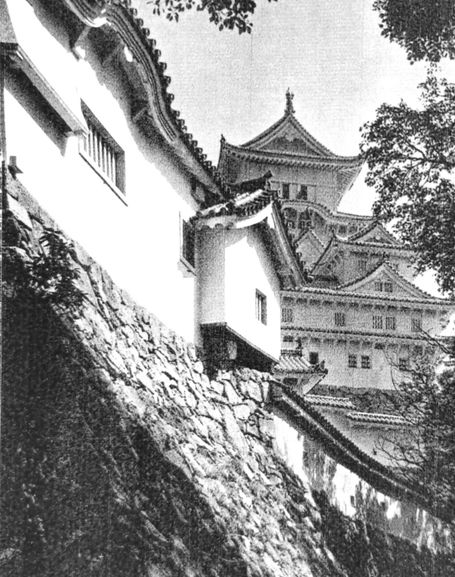

Japanese Castle Style Bays with Small Windows for Defense

Maison Planeix, Paris, France, 1924 and Himeji Castle. Adolf Loos had also followed this Japanese castle style feature, years earlier. The projecting bay and its small window in the Japanese castle was a natural result of protection against attack from which guns or arrows would be fired.

Japanese Precedents for the 'Thick' and Massive: Architectural Brutalism as Japanese Fortress Turned Monastery

Much architectural japonisme focuses on 'thin' structures: wood walls, paper sliding doors, delicate gridwork and the like. Here we look at the japonisme of the thick, not just the thin; the massive and heavy, not just the delicate and light.

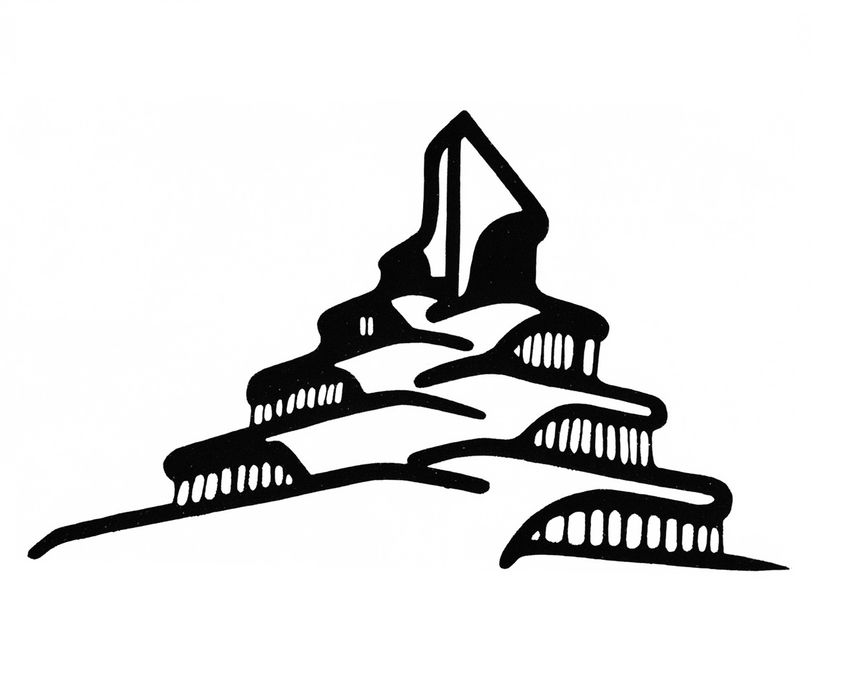

Couvent Sainte-Marie de la Tourette, Eveux-sur-l'Arbresle, France, 1953, and Himeiji Castle compared. Dense, thick masses combined with intricate forms, with a pronounced structural overhang.

The general appearance of the priory/monastery, at first glance, might seem to be quite different from that of Himeji Castle. Certainly the foundations are more like a concrete version of the Hondo (main hall) or Hikarido (hall of light) of Ishiyama-dera Temple of Shiga prefecture, or the Nigatsudo of Todaiji, Nara or other 'butai-zukuri' or 'kakezukuri' on stilts built into the sides of hills or rocky cliffs (and in that respect too, it may be surmised that the priory expresses an eclectic spirit). Especially the Ishiyama-dera structures reveal various similarities of detail, not just in the sloping hillside pillars, but design elements that remind one of the grill, gridwork, and windows of Le Corbusier's convent.

Nevertheless, the visual, tactile impact of the edifice is more analogous to that of a fortress, such as that of Himeji castle, of overwhelmingly massive solidity, with heavy, pronounced overhanging eaves, an impression which grows as one approaches and stands at neck bending proximity, looking up. Like the Japanese castle, the convent is visually and structurally divided into two major parts, the massive supporting structures below, and the supported structures above with their fine detailing of grillwork, including protruding rafters/taruki. The pronounced protrusion of the rafter-like elements in Le Corbusier's monastery is not necessary for a concrete structure, but is simply a decorative feature, echoing Japanese eave design. There are elements that may be interpreted as taking from European castles as well, as the double line of recessed windows reminiscent of Chateau de Pierrefonds. But besides that, there is much more in detail, that reflects Japanese structures more than those in Europe.

The Japonisme of the 'Thick' and Massive Continued

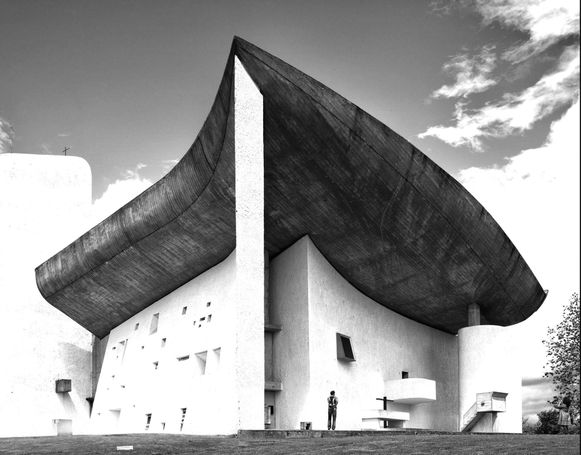

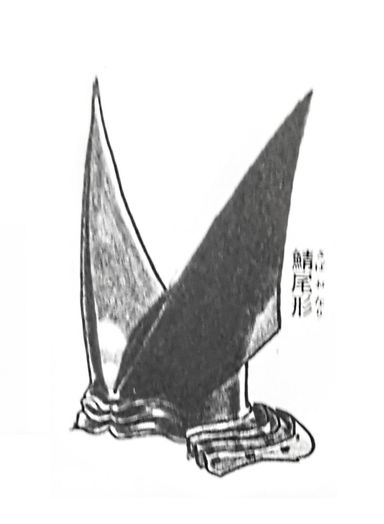

The Windows of the Chapelle Notre Dame du Haut, Ronchamp, France, 1950 - 1955 and Himeji Castle, 16th-17th century.

Note below the analogous shapes, irregular placements, narrowing of aperture, etc.

Below: Photo of wall detail with irregular shaped windows at irregular intervals near the ground at Chapelle Notre Dame du Haut, Ronchamp, sandwiched between photos of walls with irregular shaped windows at irregular intervals near the ground at Himeji Castle, Hyogo.

Below: Similar effect of light from Ronchamp windows compared with that of the gun and arrow holes of Himeji Castle at sunrise/sunset.

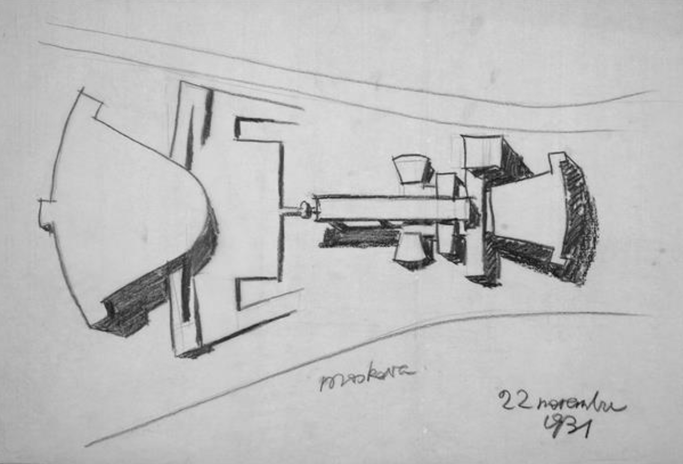

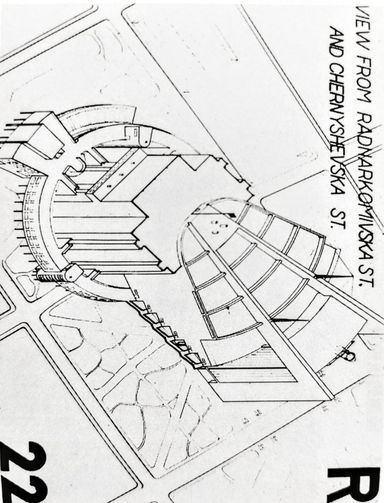

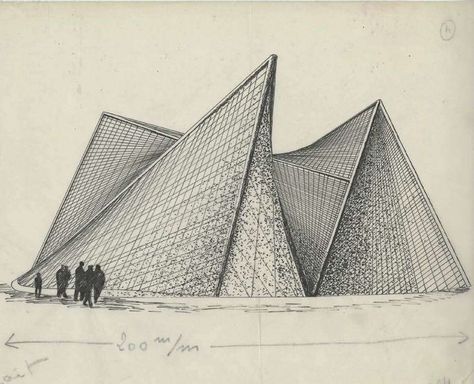

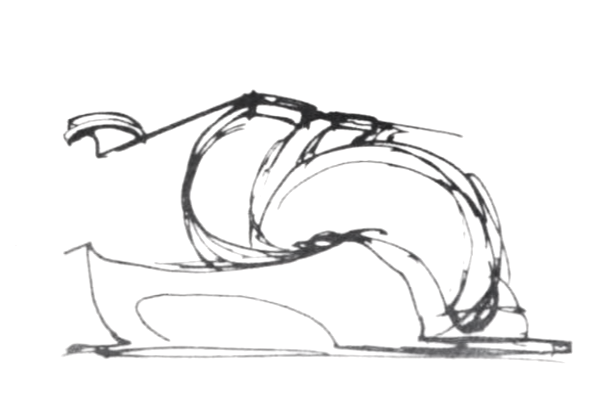

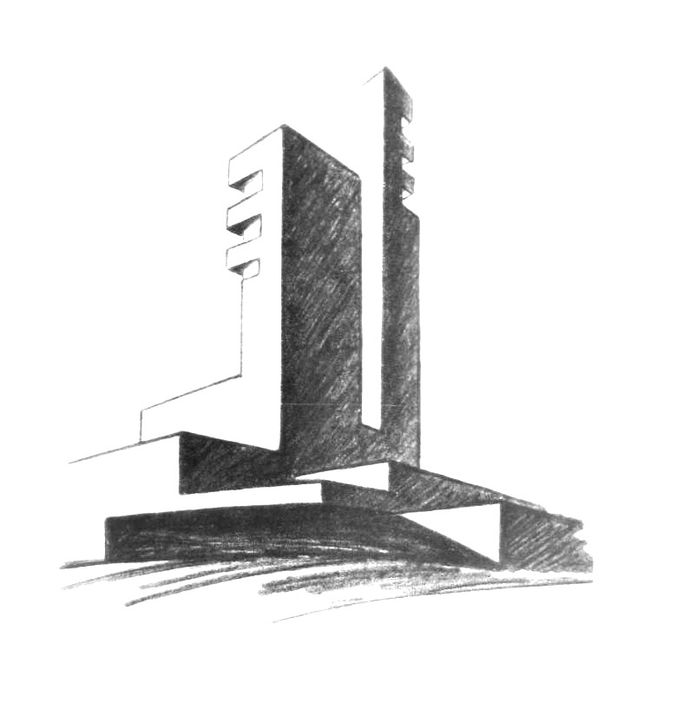

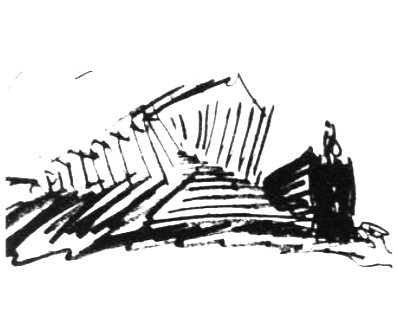

A note on the 'Bunriha' (Succession Group) of the early 1920's: faint premonitions of the Ronchamp Chapel

We should add that the asymmetric placement of small windows of differing shape and size on curved surfaces appeared in Japan in the 1920's, an age of architectural experimentation in Japan. Furthermore, curving, massed designs with a strong sculptural element and a sense of the organic, reminiscent of qualities that would be manifested in the Ronchamp Chapel, were being created and published by the Bunriha group of architects in Japan at that time. These were also characteristics of German Expressionism, which most likely was an influence upon the Bunriha, but the forms being produced in Japan seem closer in spirit to that of Le Corbusier's than those in Germany.

Below: Left, Murayama Tomoyoshi, beauty salon of Yoshiyuki Aguri, Tokyo, 1926; center column, Bunriha Kenchiku Kai 4th Exhibition, 1924 (photo of exhibits top, close up of one of the unidentified models below); right Yamaguchi Bunzo, Hilltop Monument, model, 1924. In the Bunriha exhibit photos center and Yamaguchi Bunzo's model left, note the emphasis on diagonal or otherwise angled forms in combination with sinuous and rounded shapes with flat cut surfaces and recessed areas, as well as 'protuberances' from the main body of the structures, qualities shared with the Ronchamp Chapel.

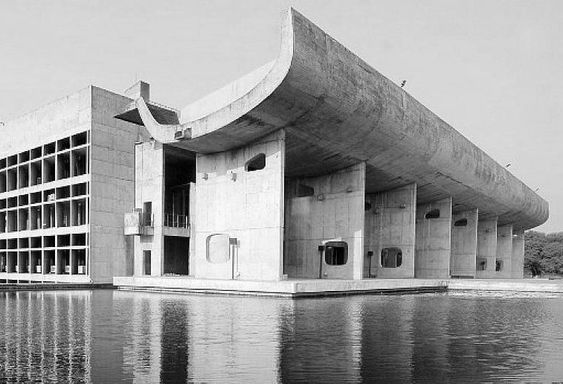

Sanjusangendo in the Shadows of Chandigarh: The Extended Play of Volume and Shadow that was Japan

Text to be added.

Sanjusangendo, Kyoto

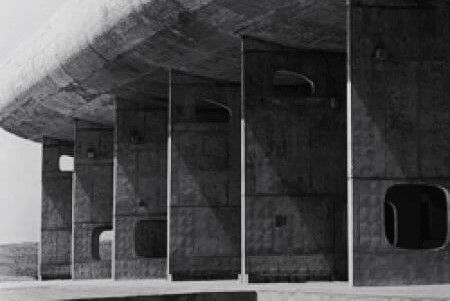

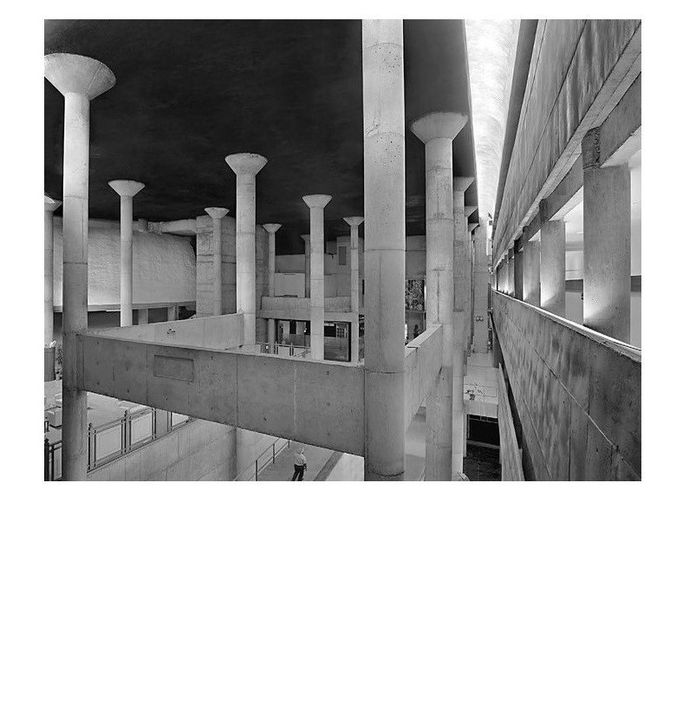

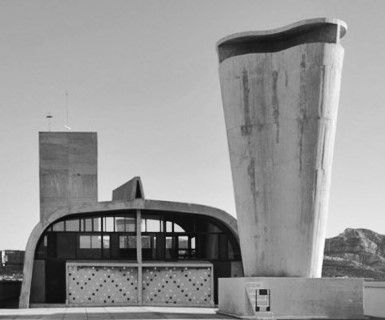

Palace of Assembly, Chandigarh

Below: Accentuation and changes in scale

Below: From a hall of divinities that is the interior of the Sanjusangendo to the abstraction and the shearing away of cultural markers in the interior of the Palace of Assembly, Chandigarh.

The Adaptation of Singular, Voluminous Forms found in Japan